ESG Economist - Investing in low-carbon technologies pays off

With the expansion of the EU ETS with ETS-II in 2027, almost all companies in the Dutch economy will have a strong incentive to invest in decarbonisation. External research shows that companies that actively invest in low-carbon technologies tend to have higher operating margins than those that do not invest in them. Bringing forward investment in decarbonisation could be beneficial for many companies. Indeed, investing in decarbonisation in the short term is more financially beneficial than investing in the medium term. In the period up to 2029, investment costs are lower than in the period after 2030. Next to that, maintenance costs are also slightly more favourable in the short term.

Within many of the economic sectors of the Dutch economy, the transition to a low-carbon or carbon-free mode of operation is now in full swing. Eliminating or reducing emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2) in particular is called decarbonisation. Almost all companies in sectors of the Dutch economy have a decarbonisation task for their processes and activities. In previous analyses we have shown that a lot of decarbonisation work remains to be done in most sectors. The 2030 target (55% emission reduction compared to 1990 levels) is now a feasible option for only a small number of sectors. This analysis also shows the big task. The sectors responsible for most greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions face a relatively large climate challenge to decarbonise their processes and products. The transition there is often complex and still faces many obstacles.

Our last publication on decarbonisation opportunities for companies in sectors (February 2024, see here) showed what the sector impact could be of available decarbonisation technologies on GHG emissions. Using 21 sector depths, in that publication we looked at the potential impact of available low-carbon technologies on the 2030 target. In the underlying analysis, we provide an update on that publication and focus on the decarbonisation trends in outline. By and large, the inventory of decarbonisation technologies in the February 2024 publication is still current.

In this analysis, we discuss the trend in greenhouse gas reductions by sectors and reveal the feasibility of the 2030 emissions reduction target in different sectors. We also show the impact of the EU Emissions Trading Scheme (EU ETS) on GHG emissions in sectors. Furthermore, as innovation in low-carbon technologies does not stand still, we conclude this analysis by summarising the decarbonisation technologies that we know are deployable in the 2025-2050 period.

Investing in decarbonisation technologies

Greater commitment to decarbonisation technologies is an important recommendation of Mario Draghi's Competitiveness Report (September 2024). Indeed, this report puts decarbonisation at the heart of the EU strategy. Decarbonisation is then the way for companies to specialise, further consolidating or expanding competitive advantage. The EU Clean Industrial Deal - due to be published at the end of February 2025 - will partly build on the advice of the Draghi report. Its goal will be to set out a strategy that will address the most pressing issues. The ultimate goal is to increase industrial competitiveness against the US and China, reduce dependence on fossil fuel suppliers and strengthen leadership on climate and sustainability. This should then be achieved by accelerating industrial decarbonisation, lowering energy prices, strengthening EU industrial sovereignty and boosting the production and innovation in clean technologies. In short, public policies will be further tightened.

Decarbonisation can be achieved in several ways and the best practice decarbonisation method varies widely by sector. For companies in one sector, switching to renewables or fuel substitution is most promising, while companies in other sectors achieve more ecological gains through electrification and efficiency measures. The emission reduction through many climate measures taken by companies regularly go hand-in-hand with economic gains as well. However, many low-carbon technologies are still under development or too expensive. Moreover, some industrial assets have long lifetimes, making investment decisions complex.

However in general, decarbonising processes and activities also pays off handsomely. Indeed, decarbonisation broadly has four benefits (after Changwoo Chung et al, in Energy Research & Social Science, February 2023). It yields energy and carbon savings (1) and, at the same time, cost savings (2). In addition, decarbonisation brings other environmental benefits (3) and decarbonisation in one sector spills over to other sectors (4). For example, an energy efficiency measure can reduce the energy and fuel consumption of many processes. It often provides cost and financial savings. Moreover, many decarbonisation options can bring other positive environmental benefits, such as water savings, raw material and resource savings and improved air quality. Finally, low-carbon ambitions in one sector have an impact on other sectors. For example, ammonia - made in the chemical industry - is widely used to produce fertilisers that are in turn used by agriculture. Decarbonising the production of ammonia has a positive impact in decarbonising agriculture as well. See also our in depth note on green ammonia.

Accelerating decarbonisation through stricter policies should not be seen as a threat. An earlier United Nations study, with data collected over the period 2013-2019, found, among other things, that companies with consistently high sustainability performance had some 4.5-5 times higher operating margins than those with low sustainability performance over the same period. A more recent study by the University of Groningen (Swarnodeep Homroy, November 2022, published in the Journal of Banking & Finance) shows that if GHG emissions decrease by one standard deviation, profitability increases by 0.14 standard deviation. Companies with low emissions have higher revenue growth, are more resilient to negative industry shocks - notably due to a more loyal customer base - and have lower operating costs (more efficiency) and lower cost of capital (lower risk).

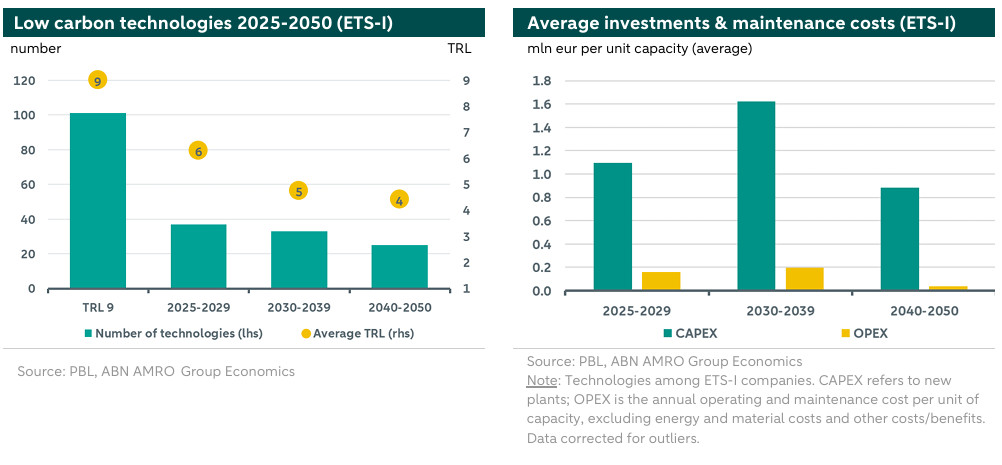

There is thus still a long GHG reduction path ahead for the Dutch economy until 2050. Currently, many decarbonisation technologies are widely available in many sectors (see also our publication with decarbonisation technologies by sector, February 2024). Our February 2024 survey showed many decarbonisation technologies are now available, such as electrification, implementation of energy efficiency measures, renewable energy production, building insulation & sustainability, as well as feedstock substitution & transition. Each of these categories has further refinements and specifications. Additional technologies are also becoming available for the period between 2025 and 2050, although the number is still relatively low. The left figure below shows the trend in the number of new or advanced technologies. However, these technologies are mainly becoming available to companies covered by ETS-I (industry and energy).

Using the ‘Technical Readiness Level’ (TRL for short) of these technologies, we gain insight into which technologies are still in their early stages of development and which have reached maturity. The scales in the TRL system represent the stage in which a new decarbonisation or emission reduction technique is at. Here, stage 1 represents the start of development and discovery. And stage 9 represents the commercial readiness of the technology. Technologies that become available between now and 2030 are currently still in phase 7. From phase 8 onwards, deployment on a larger scale is theoretically possible. In the post-2030 period, on average, technologies still have a relatively low TRL of 4-5, which means that they are currently not deployable. New decarbonisation technologies include also many further developments of existing methodologies. For instance, the further development of carbon capture and storage (CCS) for low-carbon oil production, for example, hydrogen (H2) generation from methane and biofuels, battery technologies and the deployment of green ammonia. The biggest challenge is likely to be in making these emerging technologies cost-effective and cost-efficient.

The above right figure shows the average investment and maintenance costs per period, based om data from the Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency (PBL, project MIDDEN). This shows that investing in decarbonisation in the shorter term can be more financially advantageous. Not only are investments costs expected to be lower, but maintenance costs are also somewhat lower, which is beneficial for profitability. Average investment and maintenance costs increase in the period 2030-2039. But despite the increase in costs in this period, it remains interesting to invest in decarbonisation. Because not only will the technology itself improve and become more efficient over time, but its lifetime is also expected to increase. This progress has an impact on the level of investment in this period. The right time to invest in decarbonisation technologies will vary greatly from company to company and it remains a complex puzzle. Mr. Draghi also notes that a business case for green technology is not always transparent. The combination of relatively high investments in green technologies and higher operating costs makes the whole thing uncertain. Despite this uncertainty, low-carbon technologies ultimately bring more specialisation and therefore competitive advantages, according to the Draghi report.

In addition, making a good business case for companies around decarbonisation will always remain tailor-made. The (financial and technical) feasibility, but also the effectiveness of a technology, must be considered per company (and technology). After all, not every technology is applicable in every company - sometimes also due to insufficient network capacity - and some technologies are also mutually exclusive. Moreover, it can still be very complex to make a good business case with the available decarbonisation technologies. It is necessary to have a good understanding of both the financial feasibility and the ultimate contribution to total GHG emission reduction. Accurate data on lead times, necessary investments, maintenance and operational costs, payback periods and possible subsidy schemes remain indispensable in making a sound business case.

GHG emissions by economic activity

The European Green Deal aims for net zero by 2050. The Netherlands is also committed to this. However, to achieve this goal, large-scale climate action is still needed in many sectors. For example, to reach the 2030 climate target alone (55% reduction in GHG emissions from 1990 levels), GHGs need to be reduced by 43% over the next seven years. However, the realised rate of GHG emission reductions in the period since the Paris Agreement came into force (2017-2023) is 3% per year on average. This effectively means that emission reduction must be doubled from current levels.

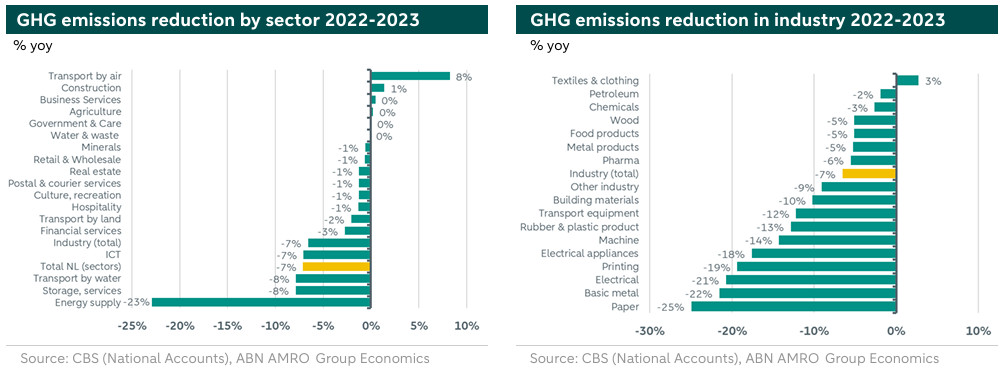

Every part of the Dutch economy will have to contribute to this. In some sectors this is more than in others. According to the first provisional emission figures from CBS (based on the National Accounts), greenhouse gas emissions decreased by 7% by 2023. At this rate, the Netherlands is on the right course, but there is little chance that this momentum will continue in the coming years. For what mainly shaped the emission reduction in 2023 appear to be mostly incidental events in some sectors.

In seven sectors, GHG emissions increased or remained the same in 2023. In addition to the five sectors at the top of the left figure above, these include the textile and clothing industry (top of right figure). Here, air transport stands out the most, as emissions continued to increase sharply. In total, 22 sectors have a GHG emission reduction rate which in 2023 is below the national average of 7% and 13 sectors are above it. Of these, the majority are industrial sectors (see right figure above). Industry as a whole has a reduction rate just below the national average. Of all sectors, energy supply contributes the most to total GHG emission reductions, with a 23% decline in 2023.

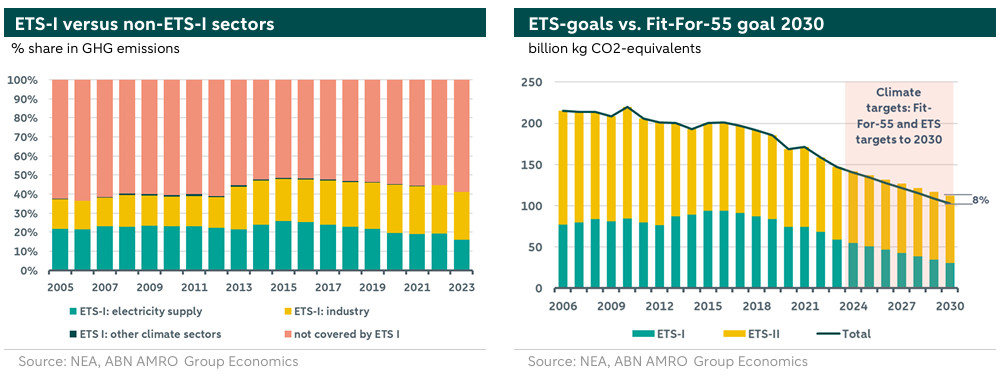

That GHG emission reductions are relatively fast in energy supply and industry is because the vast majority of emissions in these sectors are covered by the EU Emissions Trading Scheme (EU ETS), which forces companies to reduce their GHGs. For example, 97% of emissions in energy supply are covered by EU ETS, and in industry it will be 77% by 2023.

Within industry, the paper industry is a frontrunner in terms of sustainability. Not only is this sector bound by strict sustainability rules, efficiency has also been further improved. The paper industry is a heat-intensive industry, with paper drying consuming by far the most energy. In this respect, many paper producers are making more use of residual heat in the drying process. This makes a big difference in energy consumption and costs.

What also striking is that greenhouse gases in the base metal industry decreased by 22% in 2023. This was mainly due to a large modernisation and repair programme of a blast furnace at Tata Steel, which meant it was not operational in 2023. Tata Steel accounts for about 95% share of CO2-emissions of the total base metal industry and is responsible for about 4% of total CO2-emissions in the Netherlands. Given this, the shutdown of the blast furnace had a major impact. Maintenance of the blast furnace mainly concerned the control system and replacement of the refractory material in the furnace, and to a lesser extent preservation. The blast furnace became operational again in early 2024, making it plausible that GHG emissions increased again in 2024.

Many other industrial sectors also showed considerably stronger emission reductions in 2023. Collectively, however, these subsectors have relatively little effect on the total. Of more concern is the slow pace of GHG emission reductions in sectors where decarbonisation is more complex, such as petroleum, food and chemical industries. It is precisely in these sectors that emission reduction rates are relatively low.

Pace in GHG emission reduction

Despite increasing investments in clean energy and decarbonisation technologies (and innovation therein) in recent years, it is still insufficient to structurally accelerate the pace of GHG emission reduction. This is partly due to some limitations for further acceleration in a more significant step up of green investments, such as the structural shortage of personnel, the limited network capacity for electrification and also the uncertainty surrounding the supply of raw materials. In addition, transparent, supportive and stimulating government policies remain indispensable to keep the course towards climate neutrality in sight. However, it also requires greater efforts by companies across the economy.

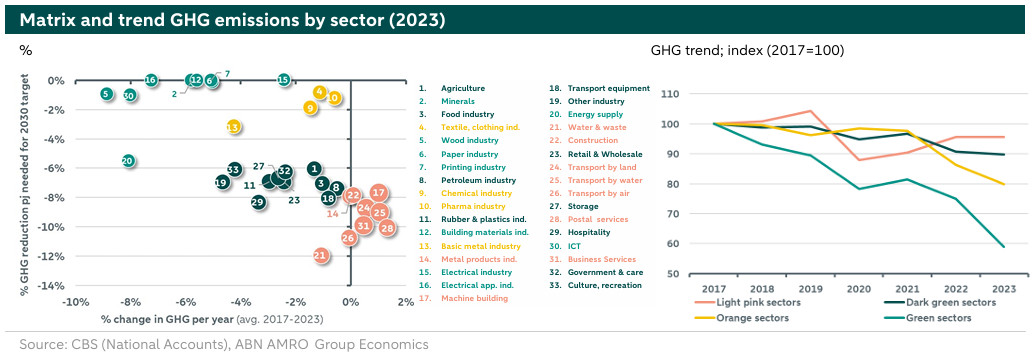

The International Energy Agency (IEA) regularly advises that renewable investments should be scaled up further. In doing so, the IEA also indicates that more public and private sustainable investments combined with the accelerated deployment of decarbonisation technologies will reduce greenhouse gas emissions at a faster pace. In further reducing greenhouse gases, it is especially important to prioritise the sectors that are difficult to decarbonise (such as heavy industry and transport). Both sectors contain numerous activities and processes that have the biggest challenges in terms of decarbonisation. The left-hand matrix below shows the different sectors plotted by average historical GHG emission reduction (horizontal axis) and the annual GHG emission reduction rate required as a minimum to meet the 2030 target (vertical axis). This shows which sectors (and subsectors of industry) are most challenged. For the sectors coloured green and yellow, either they have achieved a higher pace in reduction on average than is still needed for the 2030 target (green) or they are sectors that are at exactly the right pace (yellow). This is therefore positive. For the dark green and light pink sectors, the challenge is still great. It is likely that these sectors will not meet the target in the final years to 2030 that remain. These last two categories mainly include sub-sectors of industry and transport.

The above right figure shows the combined GHG emission reduction trend in the post-Paris period (2017-2023) of the sectors with the same colour from the matrix on the left. Here, the green line has the steepest downward trend, where GHG emissions decreased by more than 40% over the 2017-2023 period. This is mainly due to the strong decrease in emissions in energy supply, partly due to the EU Emissions Trading Scheme. The other sectors have fallen significantly behind.

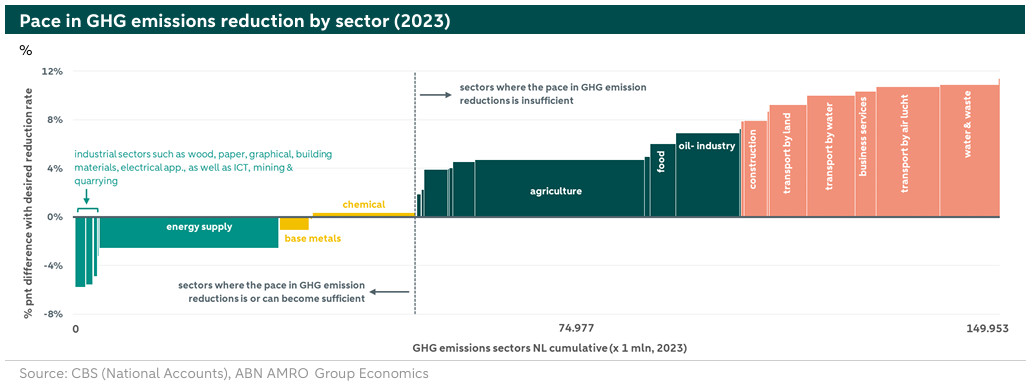

The figure below makes this lag more transparent. Here, the sectors are plotted by the amount of greenhouse gases emitted on the horizontal axis. This axis shows the cumulative amount of greenhouse gases from all economic activity in the Netherlands. In the Netherlands, this thus totalled 149,953 million kg in 2023. It follows that the width of each column represents the amount of greenhouse gases of each individual sector. From the vertical axis we can read the difference in %-point of the historical emission reduction rate (over the period 2017-2023) and the desired reduction rate needed to reach the target. The colours of the various columns correspond to the colours from the figure above in terms of progress towards targets.

The sectors plotted on the left side of the vertical dotted line have a good chance of reaching the 2030 target based on the 2023 figures. However, here, for the base metal industry, the positive position in 2023 is as a result of the major maintenance of a blast furnace at Tata Steel IJmuiden. It is therefore plausible that the emissions figures for 2024 will eventually put this sector back on the right-hand side.

On the far right, the influence of the transport sector becomes clear, with three sectors with a relatively large amount of GHG emissions and the large gap with the desired emission reduction. To get the right pace in emission reduction, the EU Emissions Trading Scheme (EU ETS) is being used. This is seen as the EU's flagship to tackle climate issues. With the success of ETS-I (which mainly includes large emitters from industry and energy supply), the new ETS-II will come into force from 2027 (for almost all companies in the other sectors).

EU Emissions Trade System (EU-ETS)

The EU ETS was launched in 2005. The system covers more than 12,000 power plants and industrial installations in 31 countries (EU-27 plus Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway (this is the European Free Trade Association) and Northern Ireland). By 2023, ETS companies in the Netherlands are collectively responsible for about 40% of total greenhouse gas emissions. The system aims to reduce greenhouse gas emissions at major emitters of greenhouse gases in industry and energy supply. This is done by setting a limit (a ‘cap’) on the amount of greenhouse gases that can be emitted by companies. That limit is determined by a quantity of allowances. This number of allowances decreases every year. Companies covered by ETS-I can only emit greenhouse gases to the extent that they have allowances for them. In addition, these allowances increasingly come with a cost. This creates an economic incentive for companies to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions further and faster, by switching to cleaner technologies.

The results so far imply that the EU ETS mechanism is an effective way to accelerate sustainability. For instance, combined GHG emissions from companies under ETS-1 have decreased by 36% since 2017, while GHG emissions from companies not covered by ETS-I have fallen by 16% over the same period. By 2023, emissions from ETS-I companies in the Netherlands decreased by 14%. This decrease is the largest annual emission reduction since the start of the system. Here again, however, maintenance of the blast furnace at Tata Steel has had a relatively large impact. But more positively, the biggest contribution was made by companies in the energy sector, where emissions fell by 23% by 2023. This decrease is partly due to a sharp increase in renewable electricity generation (mainly wind and solar power), at the expense of fossil fuels (especially gas). Emissions from industrial ETS companies fell by 8% by 2023.

The pace in GHG reductions is much slower among companies not covered by ETS-I. Since 2017, they have decreased by 16% and by only 1% in 2023. The companies not covered by ETS-I are part of the Effort Sharing Regulation (ESR). These are companies active in agriculture, small industry, waste companies, domestic transport (excluding aviation), as well as the built environment. Within the ESR, EU countries have been assigned an emission reduction target for these sectors. For the Netherlands, the target is to reduce emissions by 48% compared to 2005 emission levels. To support and encourage this target, ETS-II focuses on GHG emissions through fuel combustion. ETS-II mainly covers the built environment, road transport and small industry (companies not covered by ETS-I), because in these sectors, emission reductions have been insufficient to ultimately meet climate targets. ETS-II aims to reduce GHG emissions in these specific sectors by 42% compared to 2005 levels.

ETS-II, like ETS-I, has a cap-and-trade system. However, the difference is that ETS-II covers upstream emissions. As such, it is the fuel suppliers that have to monitor and report their emissions, and not the end consumers such as households or car users. Fuel suppliers have the first obligation to monitor emissions from 2025. ETS-II will then start from 2027. The expectation (and hope) is that relatively more companies will invest in decarbonisation in the run-up to 2027 and the final start of ETS-II, with the deployment of clean technologies gaining momentum. Together, the ETS-I and ETS-II targets contribute significantly to the Fit-for-55 target (emissions 55% below 1990 levels). It is worth noting however that even if ETS-I and ETS-II achieve their individual targets, the 55% target will ultimately be missed by an 8% gap. This gap represents greenhouse gas emissions not covered by a trading system, but also, for example, due to land use.

More investments

Most research shows that large-scale investments are still needed to meet climate targets. Not only in the technologies themselves, but also in infrastructure, for example. A good connection to the electricity grid with sufficient capacity, for instance, is a precondition. Here, the government has an important role to play. For the period up to 2030, a number of factors will be decisive, of which affordability of the transition, a reliable infrastructure, sufficient grid capacity and stimulating green demand (with, for instance, financial incentives) remain important. However, the current problems around grid congestion also mean that the price of low-carbon technologies (especially those that go hand in hand with electrification) is relatively low, as demand lags. Many companies see grid congestion as an obstacle to investing in low-carbon technologies. Once the problem of grid congestion fades, the demand for low-carbon technologies increases and with it their price. This is another argument for keeping track of congestion developments in the region and investing on the best possible moment in low-carbon technologies, especially those related to electrification.Net