ESG Economist - What do green investment needs mean for public finances?

Large gaps remain between current levels of climate investment and what is needed for a 1.5 °C scenario. The annual investment gap looks to be in the range of 2.5-3% GDP in the years to 2030 and even higher beyond that. To close the gap, the public sector may need to cover a significant proportion via both direct investments and via subsidies and tax breaks to incentivise and facilitate the private sector.

Taking into account EU funding already earmarked for climate, the national public investment gap on an EU level would amount to just over 1% GDP, though there are quite some country variations

The new fiscal rules give countries more time to repair public finances if they undertake climate investments, but ultimately they would need to consolidate even further

Net zero scenarios typically assume a surge in carbon prices, which would provide more than sufficient revenue to close the gap, but a lot would depend on whether the transition is orderly

Green public investment needs

The decarbonisation of the European economy will require large-scale investment. The public sector will need to play its role via both direct investments and via subsidies and tax breaks to incentivise and facilitate the private sector. In this research note, we look at overall estimates of the climate investment gap and how much might be borne by the public sector. We then go on to look at what might be left for national governments once EU support is stripped out and how that might fit with the fiscal rules. Finally, we assess the possible role carbon revenues could play in closing the gap.

How large is the green investment gap?

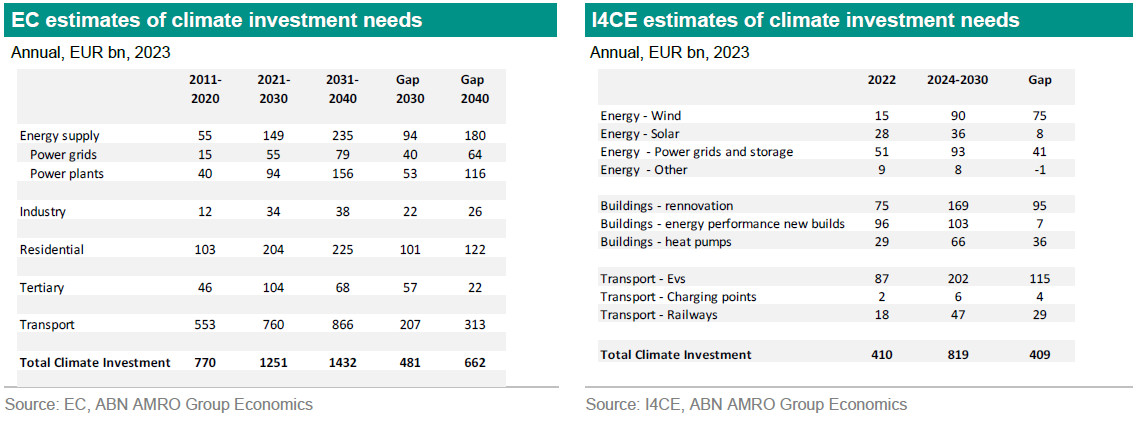

Estimates of the investment needs for the energy transition tend to vary based on coverage, in terms of the sectors and technologies assessed, assumptions about future costs and the time horizon. However, there is broad agreement that there is an investment gap and that the gap is sizeable. The European Commission (EC) estimates an annual investment gap of around EUR 480 bn during 2021-2030 compared to recorded amounts in 2011-2020 (see ). This is the amount needed to reduce emissions by 55% compared to 1990 levels. Investment needs are greater for the decade after, based on the 90% reduction target for 2040 recently proposed by the EC (see ). The gap rises to EUR 767 bn annually for 2031-2040. The breakdown by sector is set out in the table on the left below. Transportation is the largest category and includes the purchase of vehicles, though not infrastructure such as railways. This is followed by residential investment (largely reflecting the renovations needed to decarbonise the building stock) as well as energy sector investment.

Estimates from the Institute of Climate Economics (I4CE) – see publication - point to an investment gap of around EUR 410 bn (table on the right below). This is for period 2024-2030 relative to estimated climate investment in 2022. The estimate does not consider all sectors but covers some of the most important sectors in energy, buildings and transportation and provides a lot of granularity. The biggest gaps are found to be in wind capacity additions, with wind power investments collapsing in 2022 (see also our note on this here), building renovations and electric cars. Overall, the annual investment gap looks to be in the range of 2.5-3% GDP in the years to 2030 and even higher beyond that.

How large is the public green investment gap?

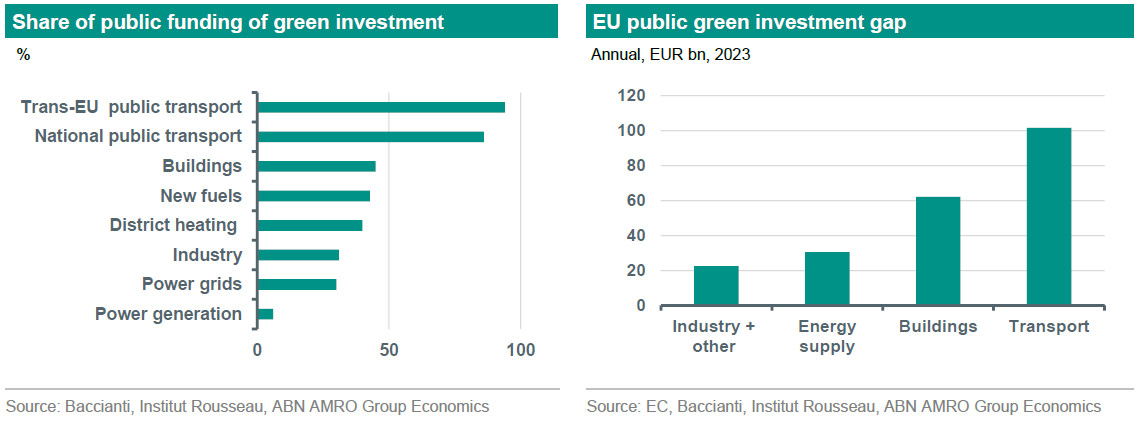

The public sector’s role in helping to close this gap varies significantly by sector. It tends to be relatively low in power generation, but higher in the transition for residential buildings and very dominant in the public transport and railways sectors. To estimate the public green investment gap, we mainly use estimates of public shares from research by Claudio Baccianti (see ), supplemented by estimates from Institut Rousseau (see ). The shares used in this analysis are set out in the table on the left, while the public investment gap by sector is shown in the table on the right. We use EC estimates of investment as the basis, but use other sources where the granularity is absent, especially in areas where the public sector would play a particularly large role. Overall, we estimate that the public investment gap totals around EUR 220bn per annum or around 1.4% GDP. Some of this would be funded collectively at the EU level, but the amount that would need to be funded by national governments would still be substantial, at around 1.1% GDP.

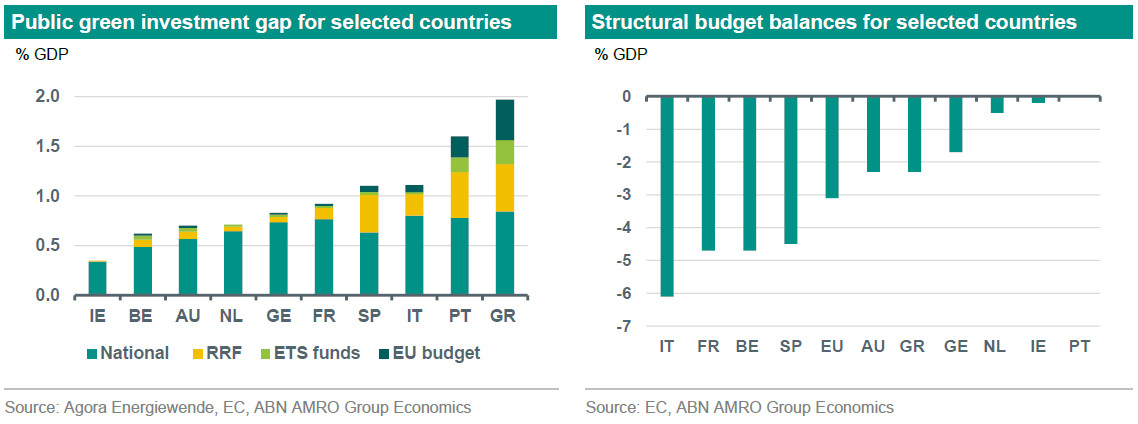

How does the public green investment gap vary on a country level?

While the total gap at the EU level is around 1% GDP, this varies quite significantly by country. We set out the numbers of the public green investment gap of the large eurozone member states, using the estimates from the think tank Agora Energiewende as a basis (see and ) supplemented by our own estimates. As can be seen, the gap tends to be higher than the EU average in a number of southern member states and below that in the north. One of the key variables driving the differences in the investment gap is the emissions gap, while the current pace of climate investments can also make a difference. There is less variation in the gap remaining for national governments, as countries with large overall gaps also tend to be the ones that are receiving the most support from common EU funds (Recovery and Resilience Facility – RRF - grants, ETS-based funds, such as the Innovation and Modernisation Funds and the EU budget). However, the RRF is expected to end in 2026, so in the last years of this decade and beyond, the funding gap for those national governments would rise significantly, unless there were to be a replacement facility.

Do the EU’s fiscal rules facilitate green investment?

Yes and no. The new fiscal rules (see our note for more details) maintain the old fiscal benchmarks of a deficit no higher than 3% and a 60% debt to GDP ratios but these fiscal targets will be reached at a different pace for each member state and the process will generally be more gradual. The medium term target is to achieve a structural deficit of 1.5% GDP. Most member states would need to tighten fiscal policy (see structural deficits in the chart on the left above for instance). Governments will have an adjustment period of four years but can obtain an extension of up to 3 years if they ‘commit to reforms and investments that will support sustainability and growth’. This means that countries have more room to facilitate green investments but will still need to eventually offset these with fiscal adjustments elsewhere. Given the poor fiscal starting point and other demands on budgets – from defence to health – the environment for governments to help close the green investment gap will remain extremely challenging for most countries.

Can carbon revenues save the day?

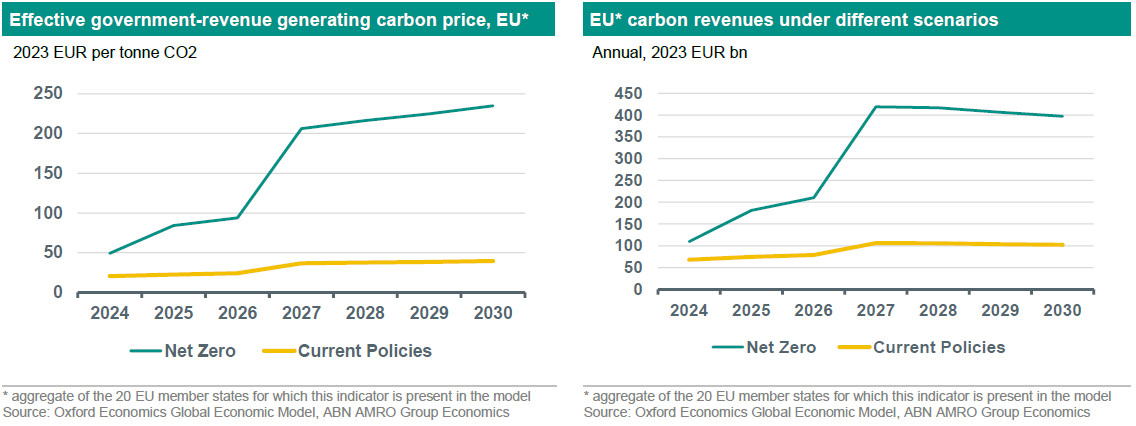

One of the EU’s cornerstones to encourage decarbonisation is the Emissions Trading System (ETS). It was extended this year to include maritime transport, while a new system (ETS 2) has been created to cover additional sectors, including buildings and road transport. Over time, carbon revenues will increase, so this could be a source of funding for green investments. Although the coverage and timelines for the phasing out of free allowances are known, there are key uncertainties in calculating the scale of carbon revenues, such as the level of the carbon price, the economic outlook and the speed of adjustment of the private sector.

We assessed carbon revenues under the Oxford model Baseline (similar to current policies) scenario and the Net Zero scenario. Under the current policies scenario, the effective government-revenue generating carbon price rises to around 40 EUR per tonne CO2 in 2030, while under the Net Zero scenario it increases to 235 EUR per tonne CO2. In the current policies scenario, additional carbon revenues from 2027 onwards would be equivalent to roughly half of the public green investment gap. In the Net Zero scenario, additional revenues would be more than enough to close the gap. However, note that this is an orderly scenario, where the impacts on the economy from soaring carbon prices are relatively benign as the private sector decarbonises at a fast pace helped by technological progress. In a more disorderly scenario, the hit to the economy would reduce wider tax revenues, offsetting to a lesser or greater extent the positive fiscal impact of higher carbon revenues. Also note that, while there is a requirement for all auction revenues to be used for climate-and-energy-related purposes, this also includes spending on adaptation, and mitigating social impact of rising prices.

Investment needs are a fiscal challenge

Large gaps remain between current levels of climate investment and what is needed for a 1.5 °C scenario. The public sector has a major role to play in helping to close that gap both directly and indirectly and this will pose a major challenge for the public finances of many EU member states, especially given the poor starting point and demands on budgets for other pressing needs. Carbon revenues could play an important role in helping to fund public green investment, though the extent will depend crucially on other policies to support the transition and the private sector’s ability to adjust.