ESG Economist - Dutch wind and solar investments falling short from 2030 target

Power generation is one of the top emitters of greenhouse gases in the EU. In 2022, European emissions from the power sector totalled 1.7 billion tonnes of CO2 equivalents (47% of total emissions in the EU), of which 95% were generated by fossil fuels, while the remaining 5% related to clean energies. These numbers indicate that the EU will only be able to achieve its ambitious targets by greening its electricity production. However, reports and regulators have been warning that most EU countries are currently lagging behind the necessary investments in order to reach the EU’s targets. For instance, according to WindEurope, only 10 GW of new wind farm capacity was financed across the EU in 2022. This number falls considerably short the 31 GW needed, on average, to be installed per year between 2023 and 2030 to meet the EU’s targets for renewable energy. Moreover, in a recent report, the IPCC concluded that “global emissions levels by 2030 resulting from the implementation of the current NDCs (1) will make it impossible to limit global warming to 1.5oC (…), and strongly increase the challenge of limiting warming to 2oC”. In line with its European peers, the Netherlands faces the challenge to drastically reduce emissions of greenhouse gases. Currently, the country depends on fossil fuels for almost 45% of its power mix. However, the targets set by the Dutch government require emissions from the power sector to decrease by around 72% by 2030. Hence, it is imperative that the electricity market transitions towards renewable energy sources. So how close are we to meet these targets? More specifically, how much is the Netherlands lagging behind the required investments? We try to answer these questions in this publication. This research note is structured as follows: first, we discuss the investment needs for the Dutch energy transition, which we derive from the government’s renewable capacity targets. We focus exclusively on wind and solar energy. Secondly, we explore the financing plans of banks, corporates, and the government. And, finally, we analyse the gap between the investment needs and the financing plans, and provide some recommendations to bridge that gap.

The Netherlands has set ambitious targets to reach a carbon neutral power sector by 2035

According to our calculations, solar and wind installed capacity would need to reach 84GW by 2030, representing an additional 46GW that needs to be installed between 2024-2030

We translate these targets into an estimate of investment needs of EUR 39bn that are required to be invested to meet the targets

We then compare this amount with what is expected to be financed via private investors

Overall, our analysis indicates that EUR 33bn is expected to be invested through corporate and project finance between 2024-2030

This indicates that investments need to step up in order for the Netherlands to meet its 2030 targets

We do not include subsidies directly into these calculations as the Dutch government provides operation subsidies that act as a price floor for energy prices, ultimately meaning that the government acts more as an facilitator rather than a direct investor

According to the Dutch government’s budget, expenditures towards wind and large-scale solar are expected to only increase slightly in the coming years

The new political landscape, following the recent elections, could result in a downward shift in climate-related expenditures

We argue that the government needs to create an environment where investments into renewable energy are deemed as profitable enough to bring in private investors

The current investment gap is a direct result of companies indicating that this is how much capacity they currently have to spend from a risk-return perspective

Stepping up subsidies for renewables and speeding up the permitting process could be measures that move the needle

Dutch investment needs for the energy transition

The Netherlands sets emission reduction targets that are relatively stricter than those at the European level, with the previous coalition agreement setting a 2030 emission reduction target of 60% compared to 1990 emissions (Europe aims for 55% emission reductions under the “Fit for 55” package). The Dutch emission reductions are not the same across sectors, with emissions from the power sector targeted to decrease by around 72% by 2030. Furthermore, the Netherlands aims for an emission free power sector by 2035.

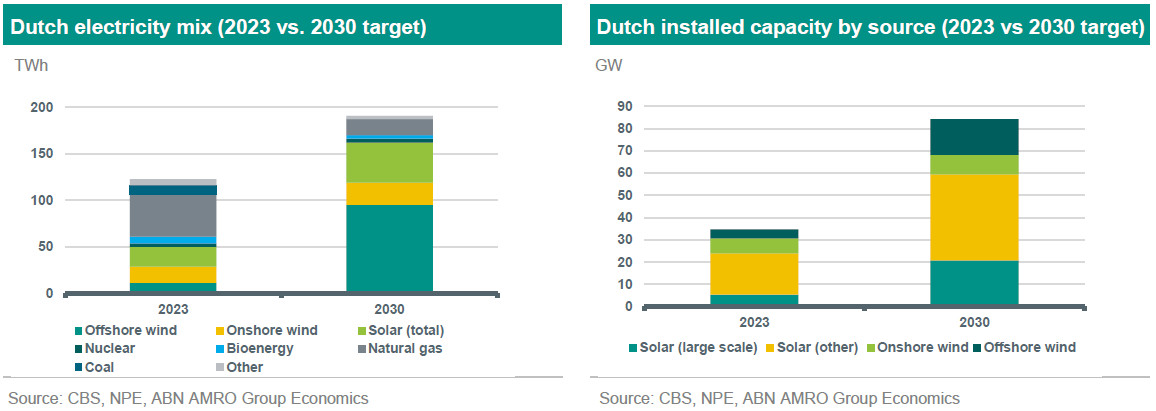

The current Dutch electricity mix is heavily dependent on gas and coal generation, with shares of 36.8% and 8.3% in 2023, respectively, as shown in the left-hand chart above. Reaching the required emission reductions in time is based on the simultaneous efforts to phase out of fossil-fuel based generation and to scale up renewable power sources, such as wind and solar. In that regard, the Dutch Coal Ban Act for electricity production guarantees the phasing out of coal-fired power stations by 2030, while gas power generation is planned to be halted by 2035. At the same time, renewable capacity is expected to increase exponentially during the transition phase, with ambitious capacity targets for solar and offshore wind. These targets are set out in the right-hand chart above. The chart depicts an overall solar capacity of 59.3GW in 2030, with 20.8GW to be deployed by large-scale solar farms. For our purpose, we only focus on large-scale investments. That is, solar PV investments by households and building’s rooftops are not accounted for in this exercise. The capacity target for offshore wind is 16GW by end of 2030 (2) and 8.8GW for onshore wind. Such targets are associated with huge investments towards 2030. Accordingly, we deliver below an estimate for the investment needs for wind and large-scale solar in the years towards 2030.

Wind and large-scale solar capacity targets for the Netherlands in 2030 are based on climate policies and ambitions as set out by the the “Klimaat- en energieverkenning” (KEV) 2022 and the Coalition Agreement. Accordingly, we adopt the capacity targets as set in the National Plan Energie System (see more ). These targets are shown in the chart on the right-hand side above.

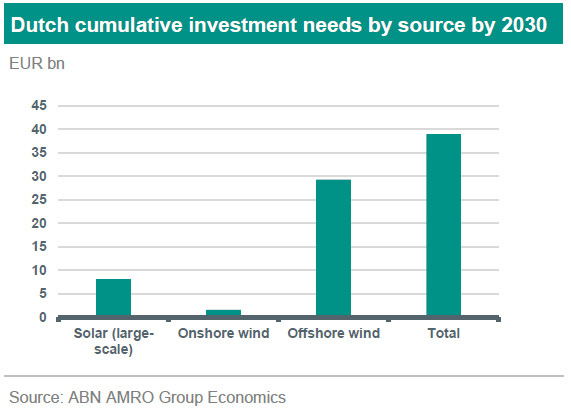

As a second step, for each of the targeted investments (large-scale solar, offshore and onshore wind) we use the expected development of the CAPEX costs per MW towards 2030 as per expectations of utility companies. This cost is assumed to decrease for solar and onshore wind and increase for offshore wind in the coming years. We explain these costs in more details in the subsequent sections. Furthermore, our investment simulations assume equal yearly capacity additions between 2024-2030.

The obtained investment needs for wind and solar between 2024-2030 are shown in the chart above. The chart shows that the total cumulative investment needed to meet the Dutch capacity targets in 2030 equals EUR 39bn, with the largest share being for offshore wind, with EUR 29.3bn, and EUR 8.15bn for large-scale solar. Onshore wind investment needs account for EUR 1.56bn. The relative small amount is attributed to the lower target for additional capacity in 2030 for onshore wind.

The financing spectrum

The second step in our research concerns the assessment of what different financiers plan to invest in order to build wind and solar capacity. These include, but are not limited to banks, corporates and governments. But first we need to clarify how a wind or a solar plant can be financed.

There are two possible capital structures: corporate finance and project finance. In a corporate finance structure, investments are carried on the balance sheet of the owners (or developer) of the project, and debt is raised at the corporate level, with the lenders having recourse to all the assets of the company to liquidate a non-performing project. Moreover, the sponsors of the project can raise capital (debt and/or equity) from different sources, such as own balance sheet financing, external private investors, funding from commercial banks or public capital markets.

In a project finance structure, the investment is carried off the balance sheet of the developer and turned into a separate business entity called a Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV). Furthermore, debt is raised at the project level, and lenders do not have recourse to the developer’s assets, only the assets of the project itself. The SPV is financed through equity from the developer, as well as debt and/or equity from other investors such as banks, asset managers, private equity, among others. Equity and debt providers are then repaid via cashflows from the project. Usually, project finance is more expensive and takes longer to finalise than corporate finance, given the higher risk and the larger number of parties involved.

Trends in the Netherlands

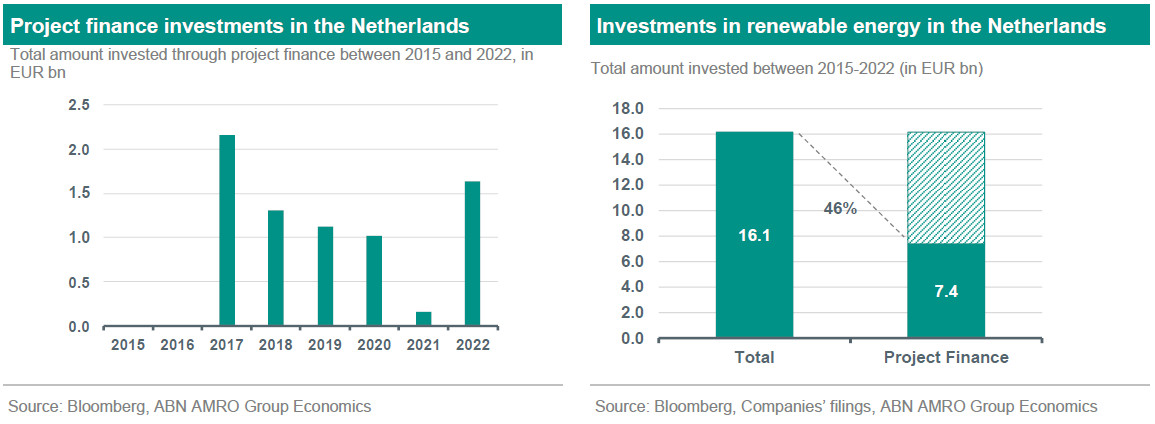

In order to assess the share of project finance used in the Netherlands to finance renewable energy projects we used Bloomberg data, which shows that a total of EUR 7.4bn of project finance loans were granted between 2015 and 2022.

As a next step, and in order to calculate the share of project finance within total investments in renewable energy, we reconcile the estimated historical project finance for wind and solar in the Netherlands (EUR 7.4bn) with the total amount invested in the same period. For the latter, we rely on WindEurope’s estimates of annual wind energy investments and on CBS’s added installed capacity per year and IRENA’s capex estimates per EUR/kW for solar in the Netherlands. We conclude that between 2015 and 2022 a total of EUR 3.4bn and EUR 12.8bn were spent on solar and wind in the Netherlands, respectively.

Hence, project finance represents an average of 46% of historical investments into renewable energy in the country. For the purpose of estimating what is expected to be invested by 2030, we assume that this share will remain constant in the coming years.

And what share of project finance is covered by Dutch banks?

To start, it is worth explaining that banks can finance renewable energy projects not only by providing credit lines to corporates, but also by investing directly in the projects through project finance. Unfortunately, the size of a bank’s project finance book is not publicly disclosed. However, loans in the form of project finance towards renewable energy projects are usually later on linked to green bond issuances. As such, by looking at the latest green bond reports of the largest banks in the Netherlands, we can get a sense of how much these parties contribute to total project finance in the country.

We looked into the Dutch-based banks that have green bond proceeds to invest in renewable energy projects. According to their latest reports, these banks have a current exposure of EUR 11.9bn to project finance in both wind and solar projects, of which EUR 3.6bn is estimated to be in the Netherlands. Of the total amount invested in the Netherlands, EUR 2.5bn were directed to wind projects, and the remaining to solar energy projects. These numbers indicate that Dutch banks are responsible for 48% of the total project finance of Dutch renewable energy projects. The remaining share is likely covered by other European and non-European banks as well as asset managers, pension funds and insurance companies.

Regarding the future, it is hard to estimate how much banks are planning to invest until 2030. Mostly because the majority of banks do not set long-term targets – ING, for instance, only sets targets until 2025. As such, our assumption is that the share of project finance coming from Dutch banks will remain constant in the years to come (at 48%).

Estimating the expected corporate financing

In this section we will analyse the projects that are financed through corporate finance capital structures. As mentioned previously, these are on-balance sheet projects, such that investments are included in the balance sheet of the project’s developer.

In order to assess the investment plans for wind and solar in the Netherlands by European utility companies we rely on the investment plans of the large publicly-traded companies and we use the company’s existing market share (as per BNEF) to estimate what would be the overall investment if all companies would follow similar investment plans.

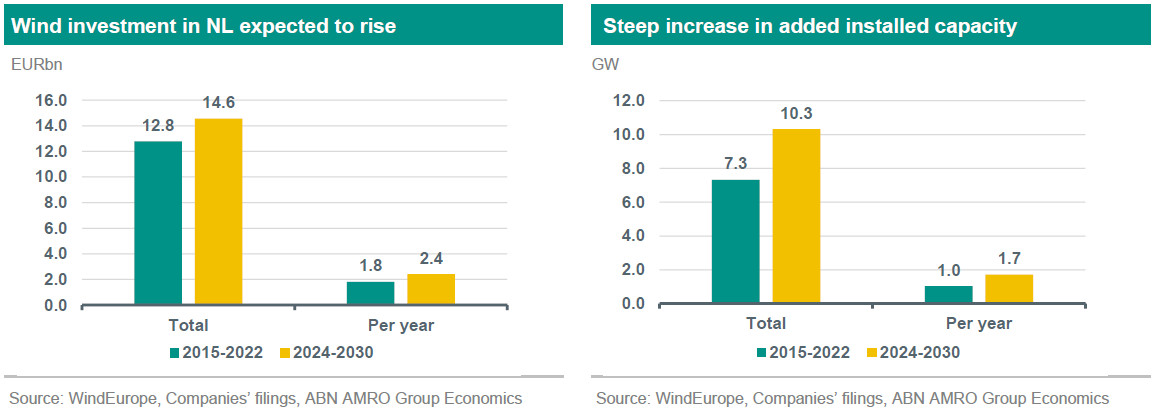

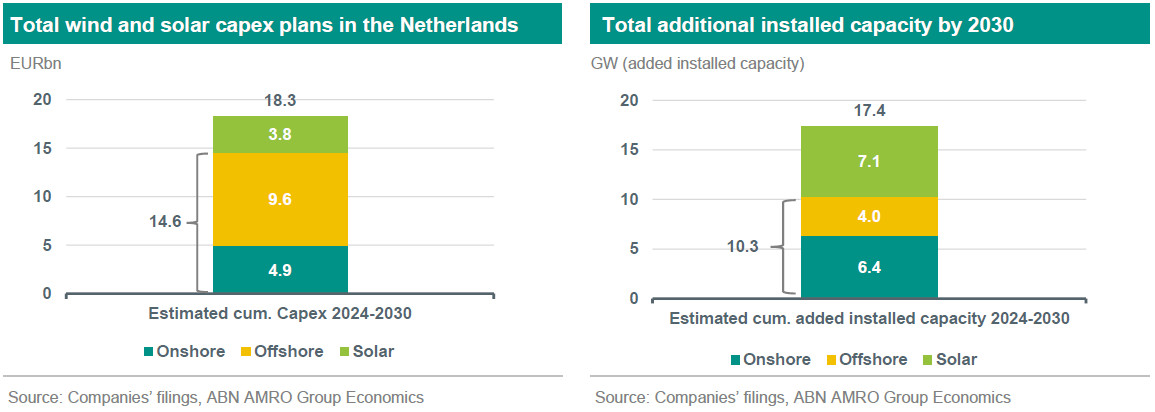

We assess that a combined EUR 14.6bn is planned to be spent on off- and onshore wind in the Netherlands between 2024 and 2030, which represents around EUR 2.4bn per year. The graph below shows how our estimated capex for 2024-2030 compares with these historical estimates. We also highlight the estimated installed capacity by 2030 based on these companies’ investment plans. That allows us to also compare companies’ plans with the Dutch government plans from an installed capacity perspective.

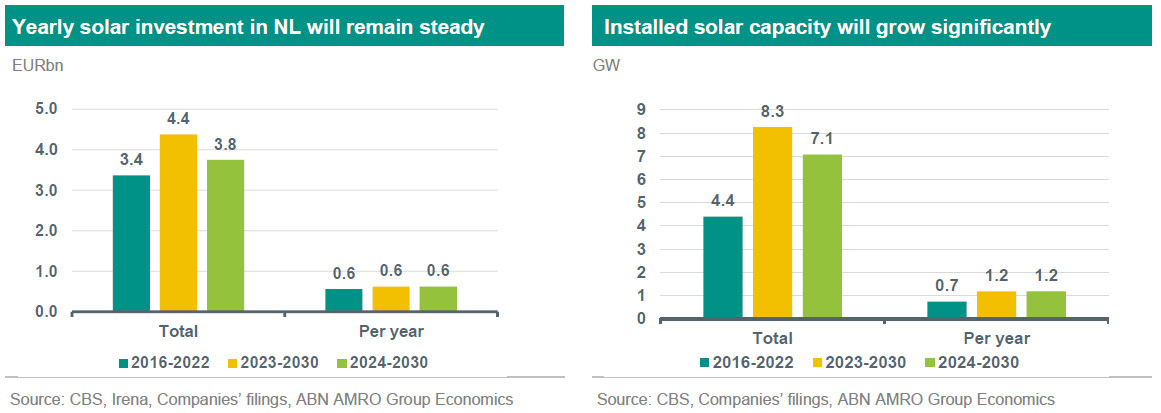

With regards to solar, we arrive at a total of EUR 4.4bn of planned investments for 2030, which translates to around EUR 0.6bn per year. We once again compare this figure with historical expenditures. One interesting insight from this historical analysis is that, while the annual added installed capacity is expected to increase from an average of 0.7 GW to a yearly 1.2 GW (see chart below on the right), the amount invested is expected to remain fairly constant. That ultimately means that companies are expecting the cost per MW to decrease over the next years. That is in contrast with the picture we see within wind investments, as depicted in the charts above. Please refer to the appendix for more details on our costs calculations.

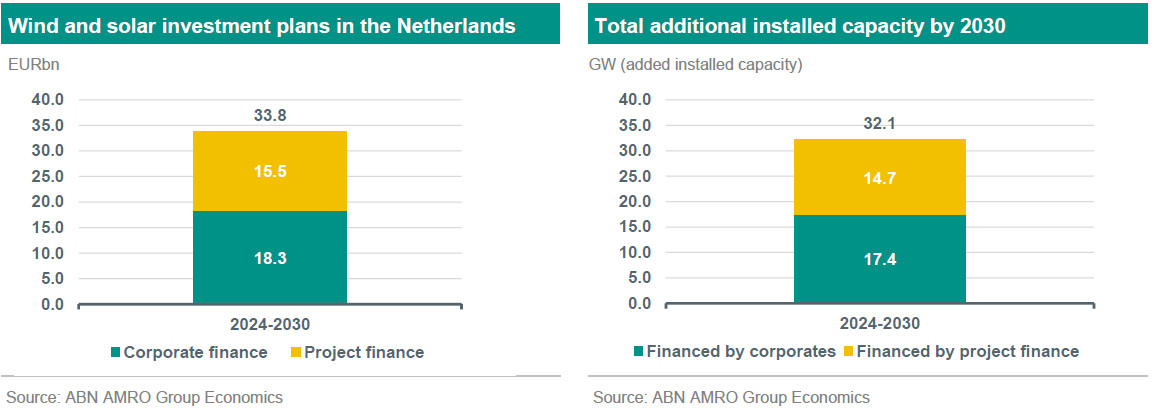

Overall, combining the analysis for both solar and wind, our analysis indicates that a total of EUR 18.3bn is expected to be spent by companies in the Netherlands between 2024 and 2030. This translates to an installed capacity that is expected to increase by 17.4 GW by 2030, which compares to only around 12GW between 2015 and 2022. That is, installed capacity would grow on average by 2.9GW per year, which compares to an annual 1.7GW between 2015-2022.

Dutch government expenditures for the energy transition

Besides companies and investors, also governments are important market participants to drive investments towards renewable energy. Hence, in this section, we will explore how much the Dutch government has invested in renewable energy in the last few years, and how much it intends to invest in the coming years.

The Dutch government has a variety of measures available to achieve the GHG reduction goals. Based on the budget for 2024, the Dutch government will spend almost EUR 6.5bn on climate-related measures (that is, not exclusively focused on wind and solar) in 2024 and this amount will increase to around EUR 11bn in 2028 (3). These amounts include expenditures under the Climate Fund, which totals EUR 35bn to be spent between 2023 and 2033 . Most of these expenditures will come in the form of subsidies and a large share of the fund will be spent in hydrogen-related projects.

As previously noted, the Dutch government’s climate-related expenditures are not exclusively directed towards wind and solar energy generation. These include categories like electricity, industry, the built environment, mobility, agriculture and others. Of those categories, subsidies for electricity represent the largest share as those will increase to EUR 4.5bn by 2028. However, we note that these also include subsidies for expanding the grid of offshore wind projects (which are out of scope of this analysis).

Dutch government provides operating subsidies for renewable energy projects

In the Netherlands, companies or other organisations that are developing renewable energy projects and/or other projects aimed at reducing CO2 emissions (such as low CO2 heat and renewable gas, like biomass) can apply for a SDE++ subsidy. The SDE++ is an operating subsidy that acts as a guarantee that projects will not incur losses, given that it pays the difference when the price of electricity falls below the cost of producing it during the operation period of the project. SDE++ subsidy is given for a period of 12 to 15 years (4). That differs from other types of subsidies, which are given upfront or in the form of a fixed production tax credit per unit of energy (such as in the US). Hence, the Dutch government acts more as a facilitator of private investments, rather than a direct investor itself.

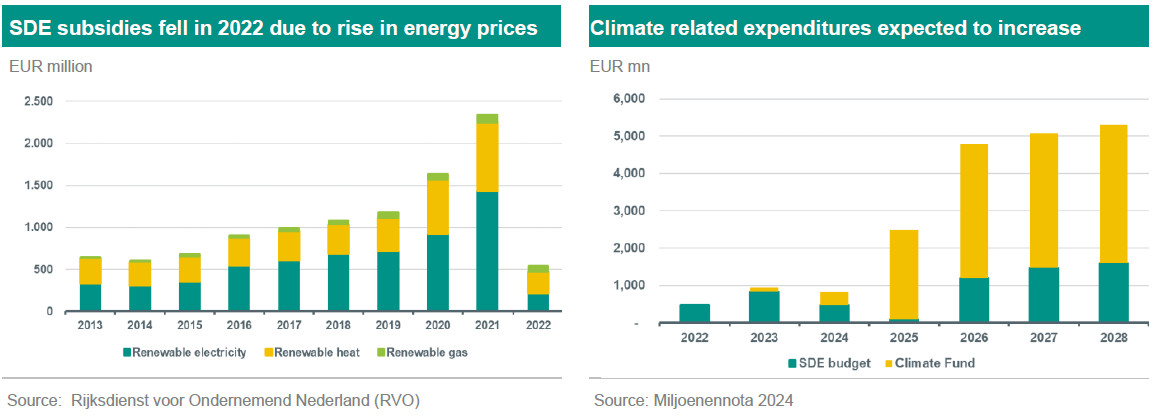

For the renewable electricity category, the SDE++ only provides subsidies for onshore wind projects and for large-scale solar projects. There have been no subsidies towards offshore wind since 2018. That is mainly because, as explained above, the total amount of subsidies paid out to the projects depends on two factors: first, the cost-price, and second, the revenue of the project. Hence, as the price of electricity increased significantly due to the energy crisis is in 2022, there was less need for offshore wind auctions to be tendered conditional to government subsidies. The graph below on the left confirms how the amount of subsidies granted to renewable electricity projects declined significantly in that year.

Looking forward, it is hard to estimate precisely how much of these subsidies are directed towards wind and solar. Nevertheless, based on the budget plans of the government until 2028, an increase in expenditures is expected on the Climate Fund whereas the SDE subsidies are expected to increase only marginally (see right graph below). Still, we note once again that the a significant share of the Climate fund is expected to be spent in hydrogen-related projects.

As we just noted, although subsidies were granted by the Dutch government for the first few offshore wind projects, no subsidies were involved at the latest tenders for offshore wind projects as these projects were profitable without a subsidy (5). Hence, one can argue that it may not be within the Dutch government plans to direct new subsidies towards offshore wind farms for the coming years, although the increased cost price of producing offshore electricity (as we previously noted) could require subsidies going forward. Whether this is indeed the case will be more clearly known when the results of the tenders for two offshore wind projects that will close at the end of March are published.

Will the new political environment result in lower green ambitions?

Right-wing parties of various flavours won the latest elections for parliament, which took place in November last year. Historically, these political parties have been more sceptical towards climate-related issues. Indeed, the election manifestos of two of the four parties currently in discussions to form government contained plans to reduce government expenditure to support the energy transition. The Party of Freedom (PVV), headed by Geert Wilders, has become the largest party in parliament and is in favour of cutting spending on climate and energy-transition related projects. This would mean a significant policy change as the previous coalition set ambitious climate targets and climate-related expenditures increased accordingly.

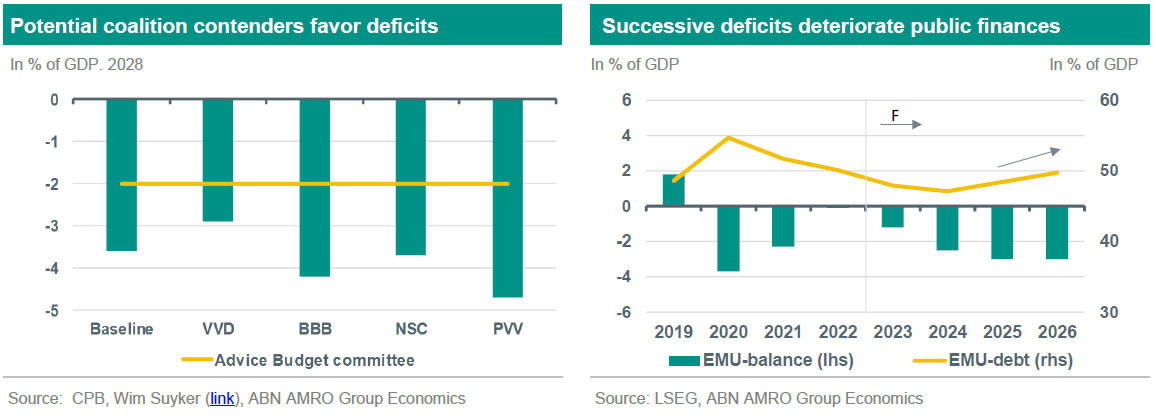

Next to this, the Dutch financial situation is expected to deteriorate in the coming years. Currently, the debt-to-GDP ratio of the Netherlands is below 50%, which when compared to its peers is considered relatively healthy. However the government has experienced deficits over the last few years, and, based on the plans of the political parties involved in the negotiations, these deficits will most likely increase further in the coming years (see graphs below). Not only will this have negative effects on both the deficit and the debt ratio, there is also the risk that extra spending will result in the crowding out of other expenditures. For instance, considering the demographic pyramid of the Netherlands, its aging society is expected to require increased healthcare costs over the coming decades. Furthermore, considering the current geopolitical situation, spending on defence is likely to increase as well. Hence, all these extra costs can come at the expense of other expenses and it remains to be seen whether the incoming government is prepared to spend sufficient amounts on climate-related projects in order to meet the climate targets currently set by the outgoing government.

Estimating the investment gap

Based on the analysis above, we conclude that:

An estimated of EUR 18.3bn is planned to be spent by companies by 2030, according to their most recent investment plans.

46% of the total investment will be funded in the form of project financing, ultimately representing a cumulative EUR 15.5bn over the 2024-2030 period.

From this amount, 48% (or an equivalent of EUR 7.5bn) is estimated to be financed by the largest Dutch banks in the Netherlands.

Dutch subsidies for wind and solar investments are not given directly, but rather indirectly as a way of providing a price floor for when energy prices drop below a level deemed to be profitable. We therefore do not consider subsidies directly into our estimates for planned investments by 2030.

Ultimately, that brings us to a total of EUR 33.8bn expected to be spent between 2024 and 2030. In terms of installed capacity, our analysis indicates that this will finance around 32GW of added installed capacity in wind and solar in the Netherlands.

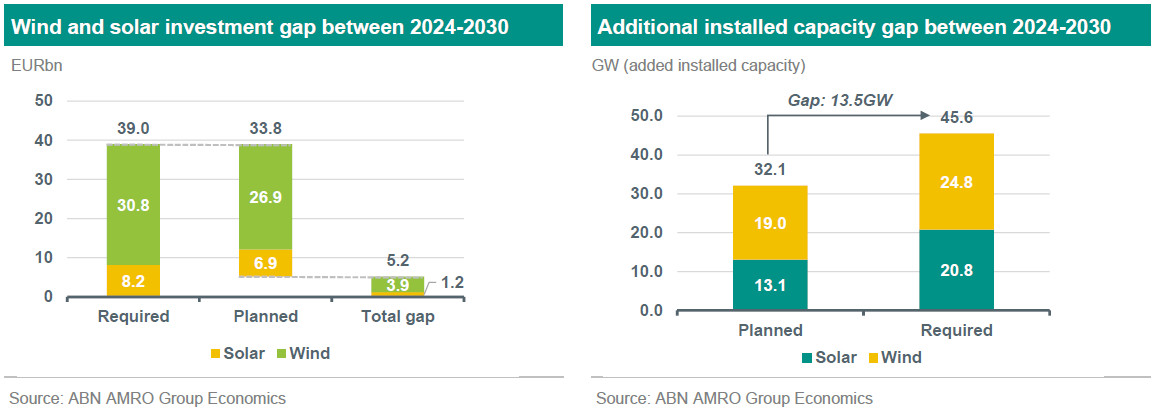

As a second step, we compare these figures with how much we assessed is likely to be required over the same period (2024-2030) in order to meet the Dutch climate targets. As previously noted, we use the same cost per MW assumption as the utilities companies from our analysis in order to have a more comprehensive comparison between investment needs and investment plans. As shown in the left chart below, the investment gap in this case is estimated to be of around EUR 5bn until 2030. This is mostly driven by wind investments, namely offshore wind, where the gap reaches nearly EUR 4bn.

In terms of installed capacity, we estimated that 32GW will be financed, but this compares to the 45GW needed in order to meet the Dutch government targets. This means that we expect a gap of 13.5GW of added installed capacity.

Overall, our analysis indicates that, based on companies’ most recent investment plans, the 2030 Dutch targets for wind and solar will not be met.

How can we bridge the investment gap?

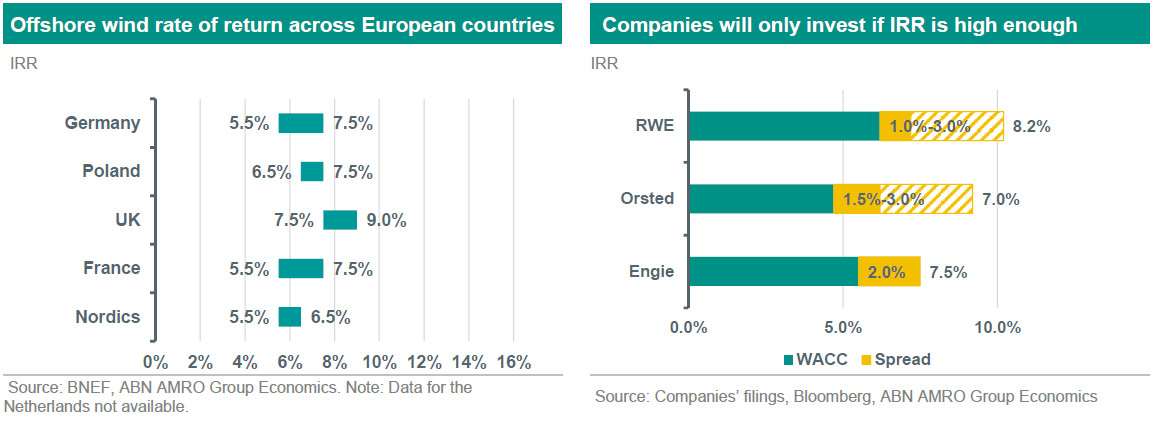

For private entities such as corporates, banks and other investors, the bottom line (and/or credit risk) remain paramount for decisions around growing the business. One could therefore argue that the persistent investment gap stems from these entities grappling to achieve rate of returns that would make these renewable energy investments profitable (and/or credit risk acceptable). As exemplified by the Danish wind developer Orsted’s recent decision, companies will not hesitate to downscale or even abandon projects that are deemed to be unprofitable (see chart below on the right for developers’ minimum internal rate of return, or IRR). That being said, governments play an important role to foster profitability and ensure that the private sector can grow renewable energy capacity, while being able to meet internal return hurdles.

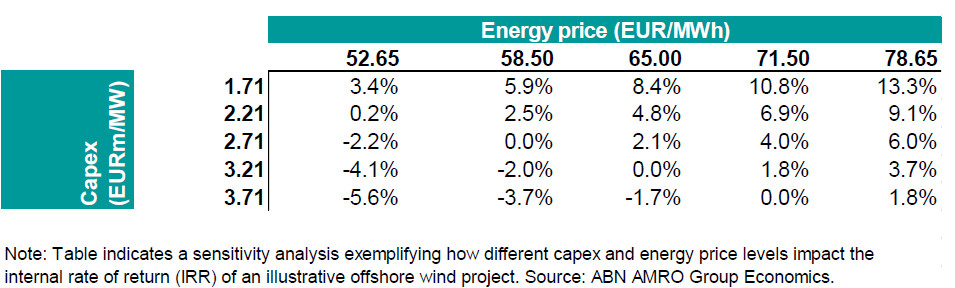

As we explained earlier, in an environment where upfront investment costs are low, and energy prices are relatively high, there is less need for government incentives, such as the ones granted in the form of Contracts for Difference (CfD) that guarantee the profitability of the project. However, the public sector needs to be ready to promptly intervene once external shocks (such as supply chain issues, rising inflationary pressure and falling energy prices) occur. An example to that is shown in the table below, where it is possible to see that once costs increase, there is need for governments to guarantee a higher energy prices to ensure a minimum level of profitability for developers (more details to the model and our assumptions can be found ).

Zooming into the situation of the Netherlands: the government no longer provides subsidies for the offshore wind market since 2018. While there was a clear rationale for that back when energy prices were surging, this reasoning no longer holds. With energy prices falling from 2022 and 2023 highs, and with companies expecting costs for offshore wind to remain elevated, the profitability of new investments is in jeopardy. Hence, it is crucial for the government to step up its financial incentives if it aims to achieve its wind targets by 2030.

Clearly, if the Netherlands aims to reach to its desired targets by 2030, the government needs to foster an environment where projects are deemed as profitable for both corporates and financiers.

Although subsidies are in place for onshore wind and large-scale solar, these seem to not be providing enough of an incentive for companies to invest in the country. The investment gap we previously estimated is a direct result of companies indicating that, under the current situation, this is how much they have the capacity to spend, from a risk-return perspective.

At the same time, the Dutch political situation does not seem in favour of providing more support in the form of subsidies. Hence, there is a chance that the subsidies will not be stepped up in the coming years.

However, besides support in the form of subsidies, there are also other policies/measures that the Dutch government can take that would not directly impact the public finances. For example, it can speed up the permit process. Specifically in the Netherlands, grid congestion and/or delays in connecting new renewable energy projects into the grid are also issues that have a direct negative impact into the project’s profitability. Our analysis shows that, all else equal, an additional 1 year delay before the project becomes operational can lead to a deterioration of around 50bps in IRR. Ensuring a timely update of policy levers to avoid unnecessary delays and associated additional costs, in particular given the sector and industry’s fast developments, is also necessary to avoid (indirect) costs that weigh into projects profitability and, consequently, investments.

All in all, the Dutch government is the ultimate responsible party for creating an environment that stimulates private financing, which plays an important role towards reaching the 2030 targets. This can be done not only via direct support in the form of subsidies, but also by guaranteeing that policies respond efficiently and quickly to bottlenecks, such as the ones created by regulatory barriers.

(1) Intended nationally determined contribution (NDC): Intended NDCs are submissions from countries describing the national actions that they intend to take to reach the Paris Agreement’s long-term temperature goal of limiting warming to well below 2C degrees..

(2) Most communications refers to a 21GW target, but this is a target to be reached by the end of 2031 and not 2030.