Global Monthly - Calm before the storm?

The global economy is on tenterhooks on the eve of the US presidential election, which takes place next Tuesday, 5 November. Polls continue to suggest the outcome is a coin-toss. The stakes could hardly be higher, with a Harris win likely to see a continuation of the status quo, while a Trump win could mean significant new barriers to global trade, and downside risks to global growth. This month, we recap our extensive coverage of the US election so far.

Global View: Next week could be the week that changes everything

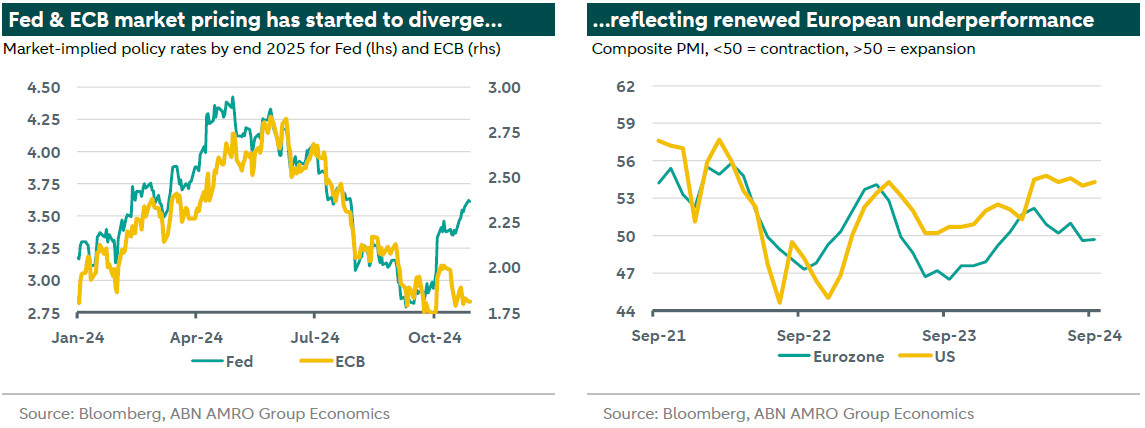

October was broadly a continuation of the developments we saw in September. Flash PMIs suggested the eurozone recovery remains subdued, nudging the ECB to forge ahead with another rate cut. Indeed, for some on the Governing Council, the outlook has seemingly darkened to such an extent recently that it opens the door to a stepping up in the pace of rate cuts – with around a 40% chance of a 50bp cut now priced in for December by financial markets. Authorities in China meanwhile continued the drip-drip of stimulus measures. And US data – though muddied by seasonality distortions – continues to point to an economy that remains on a solid footing, and this has led to a partial unwind of pricing for Fed rate cuts. With inflation coming back to target, and growth expected to converge back to trend, we still see both the ECB and Fed continuing to bring interest rates back down to more normal levels over the coming year. But all of this could be upended by the US presidential election, which after months of campaigning, finally comes to a close next week Tuesday. The US election not only has significant ramifications for the US economy, but it could impact the global economy from a multitude of angles: from geopolitics, particularly the Russia-Ukraine war and NATO; to a potentially historic rise in trade barriers, which could hit Europe and China hard, just when global trade and industry is already struggling against a backdrop of high interest rates and weak demand. This month, we – one last time – look at the range of implications the US election could have on the economy. Next month, when we publish our Global Outlook 2025, we will finally have some clarity over what lies ahead.

Spotlight: US elections are coming to a close

The US elections are drawing near, and there is no clear indication who might win

Harris’ plans represent order: the impact on the world’s economic trajectory is mild

Trump’s plans represent chaos: with both greater upside potential, but especially greater downside risk

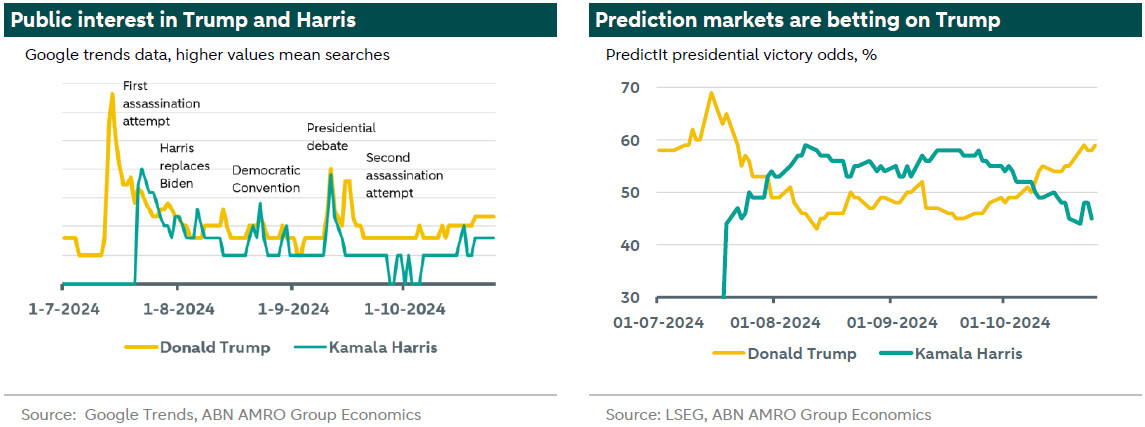

We are just a week away from the US elections – the conclusion to an incredibly exciting period – and with historic implications. The story tells itself through two data series: media attention (on the left hand side below) and betting market odds on who wins the election (on the right hand side below). The world thought Trump had won the election after the first attempt on his life on July 13th. Slightly over a week later, Biden stepped down to be replaced by Kamala Harris, who quickly gained the momentum, and kept it going following the Democratic convention and a win in the only debate between these candidates. A second assassination attempt failed to raise as much interest or put a large dent in the betting odds. Since the end of September, betting markets have clearly started to favor Trump, while professional forecasters with elaborate models, the likes of the Economist and Nate Silver, describe the election as a toss-up. With probabilities hardly moving away from 50% for both candidates, a coin-flip is as likely to be right. This is largely the result of the electoral college. Whereas the popular vote will almost surely go to Kamala Harris, the presidential election ultimately depends on a couple of hundred thousand swing-voters in battleground states. In those states, the margins are too close to call, and we’ll really need to wait until the final vote is counted.

Spurred by the impact of post-pandemic inflation, the economy is once again at the forefront of voters minds, similar to its importance in the 2008 election following the Great Financial crisis. , the state of the economy has had a large effect on who they vote for, with the typical American voter placing greater faith in a Republican to put the economy back on track. Who will be better for the economy this time around? Over the summer we made an inventory of the policy proposals by the candidates and modeled the impact of the major policy changes on the , as well as the . While the candidates’ overall policy agenda differs greatly on almost every aspect, the two primary policy proposals affecting the (global) economy are tax- and trade policy.

Trump aims to lower corporate taxes and extend the Trump income tax cuts, while Harris wants to raise corporate and wealth taxes, and extend Trump’s income tax cuts for all but the highest income households. Broadly speaking, Trump’s plan to lower corporate taxes is likely to give a boost to the economy at the expense of a greater budget deficit. The US economy certainly doesn’t seem to need it at this point, and there’s a risk of overheating. Harris’s tax rises are in contrast likely to slow the economy, but they are needed to finance a wide array of social transfers and support to lower and middle income households, which are likely to help boost aggregate consumption. Her plans to raise the minimum wage will similarly likely have a positive effect on growth in the medium term. Neither Harris’ nor Trump’s plans are sufficient to stop , although Trump’s plans accelerate the trajectory significantly.

The bigger economic impact may stem from trade policy. While Harris is likely to continue the Biden administration’s use of targeted tariffs to support strategic industries, Trump proposes a universal tariff on all imported goods. The tariff proposal started as a 10% tax on all goods and 60% on Chinese goods. Over the course of the campaign trail, this has evolved to a 20% baseline tariff, and tariffs of up to 2000% on select goods. This is a wildly different proposal from the tariffs implemented in his first presidency. There, we saw that a 15% average tariff led to prices of impacted goods rising by about 6%, and a decline of approximately 7% in consumption of these goods. The effect on aggregate price levels and consumption was too small to really discern. The non-universal nature of the tariffs allowed companies to substitute goods or procure goods from elsewhere in the world, limiting the impact. For instance, significant amounts of China trade was rerouted through Vietnam. A universal tariff makes this impossible.

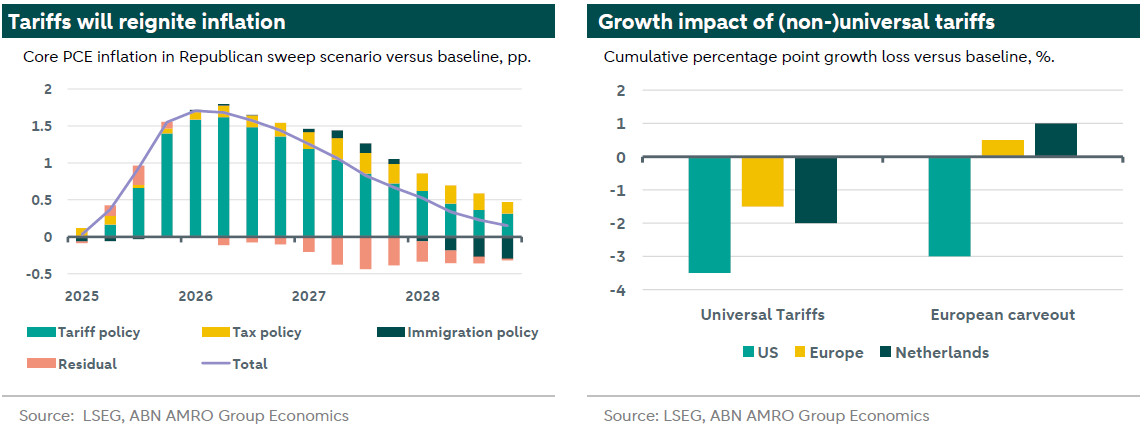

Trump’s proposal of universal tariffs will . Our analysis, based on the initial 10% universal tariff proposal, estimates that inflation could rise by up to 1.7pp relative to a scenario without such tariffs. This resurgence of inflation would force the Fed to raise rates again, or at least keep rates higher for longer. This will slow down the economy and may well put the US in a mild recession. Overall, we estimate that the US would grow by about 3.5% less over the four years, where the brunt of this hit would be in the 1.5 years following the implementation of the tariffs.

US tariffs will likely face retaliation from trading partners, which has the potential to escalate to a full-blown trade-war. We the European economy might lose out on 1.5% of growth over the four years, due to a reduction in exports to the US and the global slowdown in trade and activity as a result of the tariffs. The Netherlands, as a trade-oriented country, stands to lose even more – around 2.0%. This slowdown will put downward pressure on domestic demand and energy prices (which are likely already lower due to higher fossil fuel production under Trump), which results in the ECB easing faster and more than our baseline trajectory. Indeed, rates would go below neutral to stimulate the economy. Together with the sustained restrictive rates in the US, we could see a historic divergence in policy rates between the Fed and the ECB, putting downward pressure on the EUR/USD exchange rate. The distortions from trade-tariffs also offer opportunities. The European Commission will try to negotiate a European carveout from the universal tariffs. The eurozone would still initially be hit by weaker global trade, but over time, Europe’s improved competitive position would drive an export boost as trade is diverted from tariff-hit countries. In such a scenario, Europe, and especially the Netherlands might grow more over the four years compared to a scenario with no additional trade tariffs at all.

The above conclusions assume that Trump and Harris would actually be able to implement their policies. Even setting aside the question of whether e.g. the tariffs are election rhetoric or a negotiation tactic, the ability of the future president to implement these measures depends on the makeup of congress. These elections are less of a toss-up. The Economist estimates the probability of a Republican Senate at 72%, and of a Democrat House at 57%. Trump will likely need full support of congress to push through a universal tariff. In his first presidency he was able to push through tariffs on China imports based on ‘national security’ concerns. This case is much harder to make for a universal tariff on the entire world. Control of Congress is also likely a prerequisite for changes in the tax code and other sweeping changes Trump, in particular, is planning to make. These include various changes to the , such as a proposal to reclassify civil service workers as political appointees, which would allow the President to exert control over various federal agencies, weakening the checks and balances in the current system.

Broadly summarizing, we see a Harris victory as a continuation of the previous four years, which we judge as a benign scenario for both the US and the rest of the world. The US economy is doing well, and that is at least partially attributable to the Biden administration’s policy. A Trump victory entails a partial reversal of the past four years. While some of his plans may provide at least a temporary boost to the economy, the universal tariff would reverse progress on global trade and slow global growth. His plans to withdraw from the Paris Agreement and remove funding for climate related expenses in the IRA would revert progress made towards a more sustainable economy, hurting the longer run outlook. It is clear that the downside risks are large. But they are risks rather than realities, and given policy uncertainty, they could well stay that way well beyond the elections.