Global Monthly - What Trump tariffs would mean for Europe

Despite the rise of Harris in the polls, a Trump victory in the November election is still essentially 50-50. Trump’s most economically consequential plan is for a 10% universal tariff on all US imports. Eurozone industry is already struggling to recover from recent shocks. Tariffs would cause a collapse in exports to the US, with trade-oriented Germany and the Netherlands likely to be particularly hard hit. The policy would also drive a significant divergence in Fed & ECB monetary policy, weighing on the euro. In a scenario where the EU negotiates a European exemption, the eurozone will still see an initial hit to growth, but might ultimately benefit from the diversion of US trade from tariff-hit countries.

Global View: Tariffs likely to harm – but might actually help – the eurozone economy

Since our last Global Monthly before the summer break, developments have gone remarkably to plan. As we before the summer, the repricing in central bank rate cuts did indeed have further to run, and financial markets are now not far off our own view in expecting sharply lower rates by the end of 2025. Meanwhile, though the shift in expectations has been driven by somewhat higher recession risk in the US, we to think rumours of the US economy’s looming collapse are – to quote a famous author – greatly exaggerated. Here in the eurozone, the Olympics and other summer cultural events are giving the expected to services activity that we flagged in June. While the summer sugar high is likely to mean a hangover – or payback – in Q4, it is giving a much needed boost at a time when the manufacturing sector remains firmly in the doldrums. Indeed, following a short-lived rebound at the beginning of the year, eurozone manufacturing has persistently disappointed even our cautious expectations for a bottoming out in the sector. This led to a surprise Q2 contraction in GDP in the most industry-exposed economy in Europe – Germany. Could recent political developments offer some hope? We have long viewed the potential re-election of Trump as the biggest risk to the outlook, given his plan for a 10% universal trade tariff on US imports. In this regard, the emergence of Harris and her subsequent surge in the polls appears to have lowered that risk somewhat. But, it is still essentially a coin-toss who will win in November. Given the still-high probability of a Trump victory, this month we look at what a 10% universal tariff may mean for the eurozone economy (and the ECB) over the coming years. In the most likely scenario, the tariffs would do significant damage to eurozone industry. However, should EU negotiations succeed in delivering a European exemption to the tariffs, the eurozone might after a time benefit from the diversion in trade.

What could Trump mean for Europe?

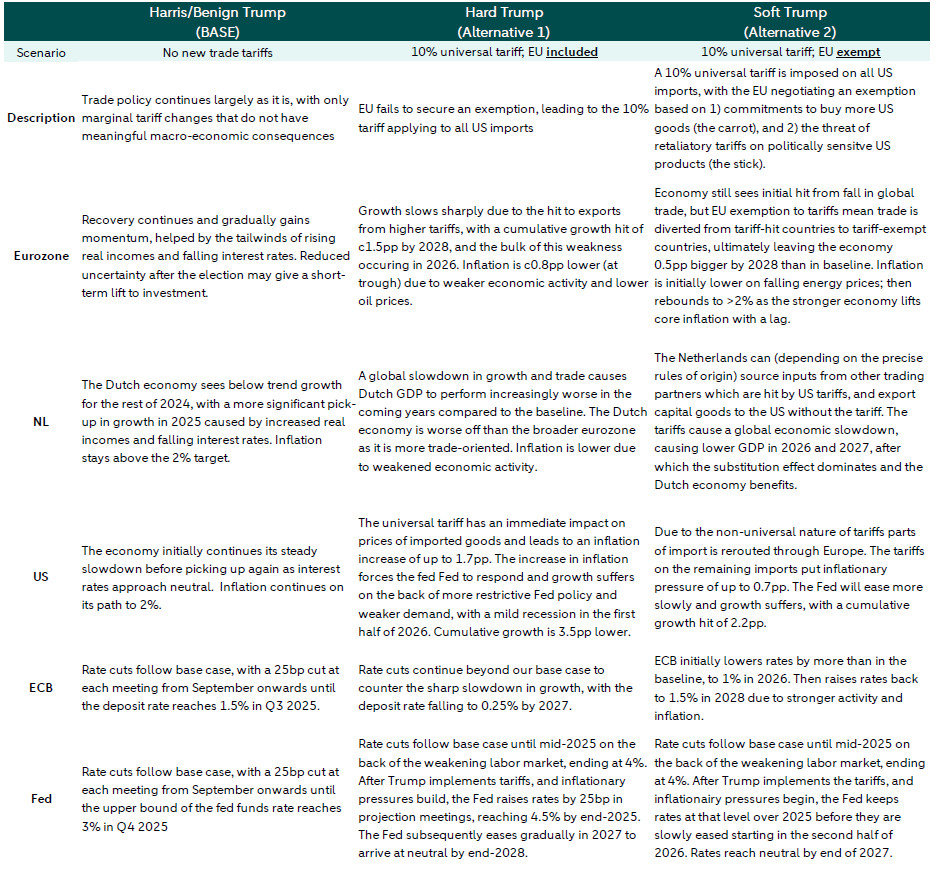

A Trump win in the November US presidential election could have many implications for Europe (1). Focusing purely on the macro-economics, however, the most consequential is his plan for a 10% universal tariff on all US imports. In our base case for the economy – which is built around policy rather than election outcomes per se – we assume either a Harris win (c.50% probability according to betting markets and election models), or a Trump win where he does not go ahead with the tariff plan (a 5-10% probability). The latter is conceivable if his economic advisors – and/or political pressure from within the Republican party – persuade Trump that the plan would be more harmful to the US economy than beneficial (2). Add these two probabilities together, and you have a 55-60% chance that trade policy stays largely the same post-election. This is therefore by default our base case. But what if Trump wins, and what if he does implement the 10% universal tariff? We look at two scenarios centred around how the tariffs could impact Europe: one where the EU is subject to the same tariff as the rest of the world, and another where the EU secures an exemption to the tariff. In both scenarios, the eurozone suffers from the hit to global trade, but in the latter scenario, the economy ultimately benefits from the diversion in trade from tariff-hit countries towards the tariff-exempt eurozone.

Alternative Scenario 1: Universal 10% import tariff (Hard Trump)

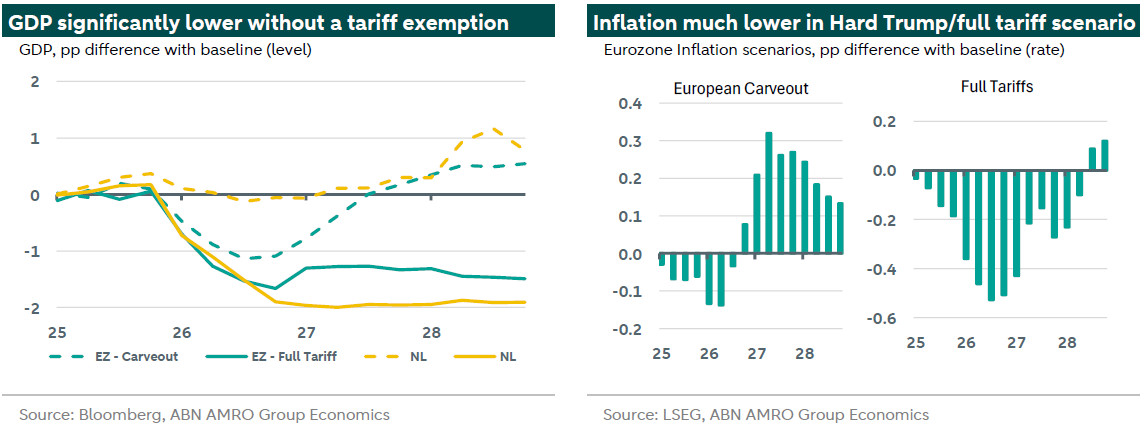

Europe would be heavily exposed to the universal tariff, with the hit to exports lowering growth by 1.5pp over a 3 year horizon. Inflation would also be much lower in this scenario, causing the ECB to cut rates back to near-zero.

The eurozone exports around €460bn annually to the US, which is 16% of total extra-EZ exports, and 4% of GDP. European Commission sources have estimated that, under a 10% universal tariff, exports to the US could fall by nearly 1/3, a figure consistent with our own analysis. Translating this directly to GDP would yield a 1.2pp growth hit. However, there would be second-round effects, via lower employment and business and consumer confidence. Indeed, the weak starting point for eurozone industry – still struggling to recover from the energy crisis – could amplify these second-round effects. Germany is especially vulnerable. Its three biggest exports to the US – chemicals, machinery and transport – are still experiencing demand shortfalls following recent shocks. The US tariffs could be the blow that tips the German economy into a more serious downturn. Taken together, and assuming the 10% tariff is implemented later in 2025 after Trump takes office, our analysis suggests the total hit to eurozone GDP would peak at close to 1.7pp, with the trough in growth occurring in Q1 2026. Such a scenario would probably not be enough to push the eurozone aggregate into a recession, but the growth impact would be akin to the energy crisis, with the economy essentially stagnating in 2026.

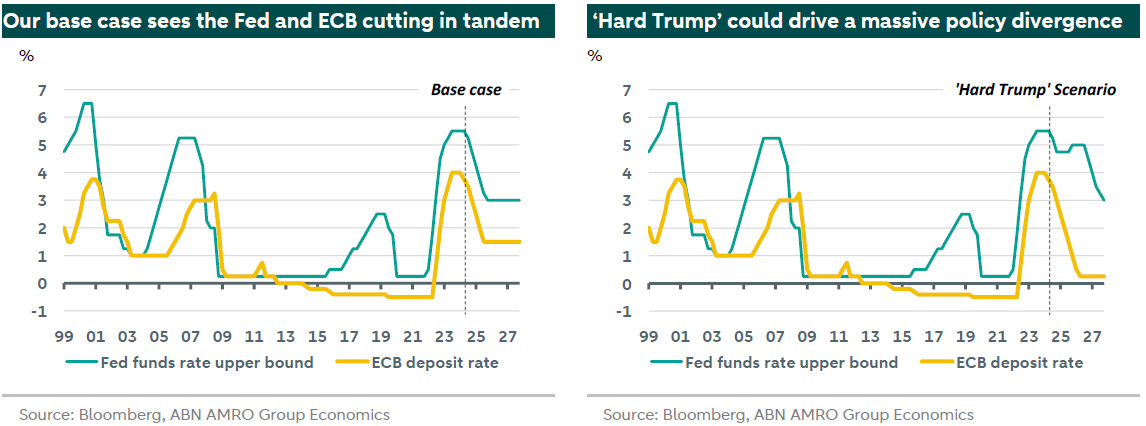

Inflation would also be much lower, with the biggest impact coming from lower energy prices – partially blunted by a weaker euro – but also through the hit to activity and confidence, which would weigh on core inflation. All told, we estimate inflation would be 0.5pp lower at peak impact (on average 0.2pp lower over the horizon), with the trough in inflation coming after the trough in GDP, in Q3 2026. Given the risk of recession and the significant inflation undershoot, we think the ECB would continue to cut rates well beyond our current base case (which sees the deposit rate falling to 1.5% by late 2025), with rates falling to 0.25% by early 2026. However, as we discuss later, the reaction of the ECB will also depend significantly on how the Fed responds to the growth and inflation shock in the US.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

Box 1: Trump Tariffs and the Netherlands – Economic structure and position in supply chains amplify impact

The impact of the two Trump tariff scenarios (see here for an explanation) on a specific country depends on the economic structure and its position in global supply chains. As a trade-oriented country with a high degree of participation in global value chains, high-value added goods exports to the US and as an entry point to the European mainland, our analysis shows the Netherlands stands to be significantly impacted (positively and negatively) in both Trump tariff scenarios. Additionally, but outside the scope of this analysis, are potential additional trade restrictions on the semiconductor sector. The semiconductor sector has become a flashpoint in US-Chinese rivalry, making additional measures possible. This sector has become increasingly important for Dutch exports, and further restrictions could amplify the effects described below.

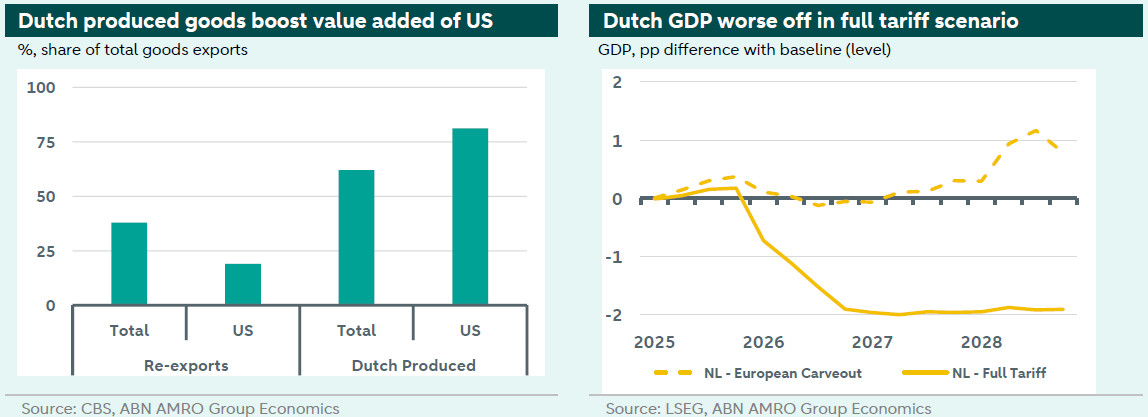

Dutch-US trade: Value-added and capital goods heavy

Some 6% of Dutch goods exports are destined for the US, with around 20% constituting re-exports and 80% being Dutch-made goods. The value-added on domestic produce is significantly higher than for re-exports. This is visible in the GDP contribution of domestic produce exports to the US, which averages 0.8% of GDP (average 15-20) according to the . It ranks fifth, even taking into account EU countries. Capital goods are the biggest export product: machines and transport (22.6% of total exports to the US) and chemicals (15.4% of total exports to the US). The high degree of internationalization of Dutch trade also affects Dutch-US trade: from the product groups that Dutch firms export to the US, over half of the inputs needed are imported from other EU countries.

Full tariff scenario: International focus of the Netherlands means it is worse off than the broader eurozone

In the full tariff scenario, a global slowdown in growth and trade causes Dutch GDP to perform increasingly worse in the coming years compared to the baseline with no tariffs, with GDP a cumulative 2% lower by 2027. Relative to the broader euro area the Dutch economy is worse off. The impact is amplified by the fact that compared to the EU-average, the Dutch economy is more trade-orientated and is more international supply chains. However, to earlier tariff episodes, we initially observe a frontloading effect in 2025. The Dutch economy benefits from increased trade from companies anticipating the tariffs. From 2027 on, the GDP hit versus baseline stabilizes, but lower trade volumes still weigh on Dutch potential growth.

European carve out scenario: Substitution later on means the Dutch economy profits after a global slowdown

In this scenario the euro area and the Netherlands in particular ultimately benefit from substitution effects, as US trade shifts from tariff-hit countries to the eurozone. The Dutch product mix helps here as Europe and the Netherlands become increasingly attractive to import capital goods from. The Netherlands can – depending on the precise rules of origin – source inputs from other trading partners which are hit by US tariffs, and export capital goods to the US without the tariff. However, in this scenario the Dutch economy is not fully isolated from adverse effects. The tariffs cause a global economic slowdown which is why Dutch GDP is lower in 2026 and 2027, after which the substitution effect dominates and the Dutch economy benefits. (Aggie van Huisseling, Jan-Paul van de Kerke)

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

Alternative Scenario 2: EU exemption to 10% tariff (Soft Trump)

The EU negotiates an exemption to US import tariffs. With the tariff still applied to other countries, the eurozone is still hit in the near-term by weaker global trade. Over time, though, Europe’s improved competitive position drives an export boost, lifting growth and inflation relative to the baseline.

There is also a scenario where Europe could actually benefit from the Trump tariffs. reported last month that EU officials are preparing a ‘carrot-and-stick’ two-step strategy to persuade Trump to exempt the bloc from the 10% universal tariff. First, officials plan to offer to buy greater quantities of certain US goods in order to lower the EU’s trade surplus with the US. If this offer is not accepted, the approach would be to target politically sensitive US imports with tariffs of 50% or more.

Assuming officials succeed in the negotiations and achieve a European exemption to the universal tariff, the eurozone would still see an initial growth hit from the overall decline in global trade (and global growth) that would result. However, over time, the European exemption would lead to an increase in eurozone exports relative to the baseline, as Europe’s competitive position improves relative to its trade rivals. We estimate that growth would be boosted by around 0.5pp by this rise in exports. Slightly higher inflation (c0.3pp at peak) in this scenario – resulting from stronger economic activity – also raises the risk that the ECB lowers rates more gradually than in our base case. Alternatively, and depending on the precise timing of the growth and inflation impact, the ECB may later opt to modestly raise rates again to contain a rise in inflation, particularly in an environment where Fed policy rates might still be well in restrictive territory.

What about the US?

The US economy a is much weaker than in the baseline in either tariff scenario scenario, although the weakness comes somewhat later than in the eurozone in the Hard Trump scenario – via the monetary policy channel. This is because the universal tariff significantly raises inflation to well above the 2% target in the US, causing the Fed to either ease more slowly (Soft Trump), or to restart rate hikes in late 2025 (Hard Trump). In the latter scenario, this ultimately pushes the economy into a mild recession by early 2026. In the Hard Trump scenario in particular, we could be in for a rollercoaster ride with interest rates, as rates are initially raised to counter inflation risks, but and then lowered to fight the subsequent recession. For more on the macro implications of the election specific to the US, see .

Fed-ECB policy divergence would weigh on the euro, limiting ECB’s space to act

Absent a European carve-out (Soft Trump), a striking feature of the full tariff (Hard Trump) scenario is that it would lead to one of the biggest and most sustained monetary policy divergences between the Fed and the ECB since the launch of the euro in 1999. With the Fed raising rates just as the ECB continues to lower rates, the widening interest rate differential is likely to weigh on the euro, perhaps briefly to below parity. Given the upward impact on inflation stemming from a significantly weaker euro, we think the ECB would be mindful of the policy divergence with the Fed, and would seek to balance the need to support the economy via lower rates against the need to hedge against upside inflation risks via currency weakness. Related to this, a weaker euro would by itself do some of the easing work for the ECB, as it would (partially) offset the competitiveness hit from higher trade tariffs (3). This in turn lessens the need to cut rates. Given how iterative the various macro-economic, financial market, and policy interactions are, there is naturally significant uncertainty around the precise policy path central banks would adopt. A weaker euro than we posit here could mean fewer ECB rate cuts, while a more limited FX market reaction could give the ECB more room to lower rates than we describe here.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

Box 2: Tariffs 101 – How do tariffs affect the economy?

From a (global) welfare perspective there is consensus among economists that tariffs constitute a net welfare loss. Trade liberalization over the past decades has led to lower trade costs, which encouraged trade, regional specialization, international competition and economies of scale. The recent rise of , exemplified by the possible Trump Tariffs, risks reversing these net benefits. What are the channels of impact of tariffs on the economy? We highlight the most important channels:

1. The trade channel: The knock-on effects of higher trade costs

Tariffs increase the costs of trade, which lowers demand as well as the of traded goods, and changes their price. Higher trade costs also induce switching to domestic producers. Moreover, tariffs lead to a misallocation of production factors across countries. Higher trade costs and barriers to trade hinder the optimal allocation of production and prevent specialization. Due to the net welfare passed on to consumers, resulting in inflation. In the medium term there is the additional negative effect on productivity. Less international competition lowers incentives for innovation, and less productive firms stay in business, lowering aggregate productivity.

2. Uncertainty lowers (investment) activity

As the 2018 US tariffs showed, businesses anticipate tariffs by frontloading imports and raising prices to circumvent the impact of tariffs. In general, uncertainty over trade policy has negative consequences. For instance, business investments are postponed. This has a direct effect on economic activity (less investment), but globally speaking, lower investment also lowers demand for capital goods exports leading to an indirect effect on economic growth in regions that rely on capital good exports. Uncertainty over future trade policy also plays a role in financial markets as it may induce financial stress and tighten credit conditions, which limits the optimal allocation of capital.

3. Amplification via Global Value Chains (GVCs)

In recent decades, global trade has been increasingly optimized in global value chains where firms across different countries work together optimally and goods cross borders multiple times. This integration means the adverse effects of tariffs on trade might be as the existing value chain is not optimal anymore. Countries more intertwined in GVCs, such as the Netherlands, or specific goods which are characterized by a global value chain, such as the supply of semiconductors, risk being more adversely affected. (Jan-Paul van de Kerke)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

In the table below we summarise our three main scenarios for trade tariffs and their macro-economic and policy implications.

(1) Geopolitically, the most consequential will be Trump’s approach to NATO, a topic that is well beyond the scope of the analysis we present here. If Trump were indeed to win in November, we would explore other potential scenarios and channels of impact in greater depth.

(2) The plan could also run into legal trouble. Strictly speaking, trade policy is up to Congress. In his first term, Trump got around this legal barrier by invoking a national security provision when he put tariffs on imports from China. With the universal tariff, it is less clear that this would be possible. A lack of congressional majority could then scupper the plans.