Is the US heading for recession?

Global Macro: US recession risk has risen but should stay contained, despite market worries. As the US economic slowdown has gathered momentum, and the BoJ brought an abrupt end to the yen carry trade last week with its surprise rate hike, global markets have entered much choppier waters. Equity markets have tumbled across advanced economies, and the VIX has shot to levels not seen since the onset of pandemic lockdowns in 2020. Against this backdrop, markets now price a much more aggressive rate cutting path by the Fed, with chatter of even an intermeeting rate cut. Are the fears over the US economy justified, and how likely is the Fed to follow through on market rate cut expectations? Moreover, what will all of this mean for Europe?

As we describe below, the weakening in the US labour market does warrant some concern, but the significant increase in labour supply means the rising unemployment rate is likely overstating that weakness. Big picture, the labour market remains very strong, and provided that the data starts to show some stabilisation – as we expect – then US recession risk should remain contained. Still, as we described in our Fed comment last week, the shift in the data is enough to have caused the Fed to look in a more balanced way at both sides of its dual mandate, and is consistent with our call for the Fed to start cutting rates in September. Given the sharp tightening in financial conditions since then, the risk now is that they cut by more than in our base case in order to offset that.

What about an intermeeting Fed cut? Or could the Fed start with a 50bp move?

Provided that markets begin to stabilise in the coming days, we think a move by the Fed before the September FOMC meeting is unlikely. Such a move is not only unwarranted by the macro data, but it could also backfire in financial markets, suggesting there is more to worry about than there really is. The Fed is more likely to want to project confidence and stability, and emphasise that it will act appropriately to support the fulfilment of its mandate.

A 50bp cut at the September meeting has become more likely, particularly with such a move now more than fully priced by financial markets. However, there is a long time between now and the 18 September meeting. If the labour market data rebounds in August, and financial markets stabilise, then a 25bp cut may start to look more appropriate again.

US unemployment is rising, but for different reasons than in the past

Last Friday’s labour market report generally surprised on the downside, and raised fears of a strong and sudden downturn in labor market conditions. The overall sentiment was captured by the triggering of the ‘Sahm rule,’ which is an early recession indicator based on developments in the unemployment rate. In particular, it states that ‘When the three-month moving average of the national unemployment rate is 0.5 percentage point or more above its low over the prior twelve months, we are in the early months of recession.’ The rule is based on an empirical regularity, and has been successful in identifying downturns in real-time in previous cycles. It is however by no means a law of nature; such rules summarize complex economic dynamics and are only accurate if those dynamics exhibit the same pattern. Another well-known and historically successful recession indicator, the inverted yield-curve, has been predicting a recession since 2022, but it has yet to materialize.

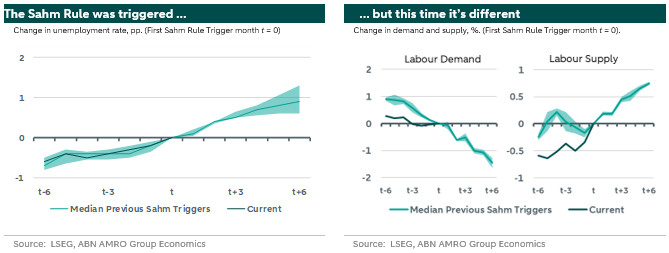

Based on an analysis of the labour market around Sahm Rule triggers since 1960, we think it will also fail to provide the right signal. The charts below show developments of a number of statistics in the year around initial triggers, along with the distribution across cycles (1). The left-hand chart shows that the unemployment rate is developing exactly in line with historical patterns around Sahm Rule triggers, which is to be expected. However, the underlying dynamics are distinctly different. In previous cycles, we saw a strong decline in labour demand, while labour supply was relatively stable (2), leading to an increase in the unemployment rate due to lack of demand. This time, labour demand – though weakening – is more stable, and the rise in unemployment stems largely from stronger than usual increases in labour supply.

Increased labour supply through stronger immigration is seen as one of the primary reasons why the US economy showed such resilience through the Fed’s tightening cycle. It also provides an explanation for the recent developments in the labour market. As the economy is gradually slowing down, the economy has more trouble absorbing the additional labour. The increased difficulty in finding a job is ultimately likely to reduce migrant inflows and therefore excess labour supply, thereby significantly reducing the upward pressure on the unemployment rate. Importantly, for the near-term, since the rise unemployment is not as uniformly driven by a decline in demand, it is also less likely to have a strong impact on consumption and growth. With that said, sentiment in financial markets – where US consumers are heavily invested – may act as a bigger drag. In this regard, the Fed has a strong interest in offsetting this tightening of financial conditions.

(1) For the left-hand chart, we show the difference between the unemployment rate six months prior to six months relative to the level at the initial trigger of the Sahm Rule. The shaded area represents the interquartile range across the different episodes. The right-hand chart is the same but shows the percentual difference relative to the value at the initial trigger of the Sahm Rule.

(2) Labor demand is measured as Total employed plus job openings. Labor supply is measured as total employed, plus total unemployed, plus the marginally attached and discouraged.

Europe not immune to US slowdown, but cyclical starting point makes it less vulnerable

Eurozone macro data has also disappointed in some areas – particularly in Germany, and particularly in the manufacturing sector – but overall the economy continues to gradually recover from the energy crisis. This is being helped by strength in the services sector, and in peripheral eurozone countries that are seeing support from record tourist inflows and European recovery fund investment. Indeed, in cyclical terms, the eurozone is in a different place to the US. Following the hit from the energy crisis, real incomes are growing strongly, and the starting point from a consumer perspective is much less vulnerable. In contrast to the US, where the savings rate is historically low, the eurozone savings rate has remained historically high: put another way, there is little further room for consumer retrenchment in Europe, while the start of rate cuts by the ECB will if anything drive a cyclical pickup in spending. This does not mean Europe would be immune to a possible US recession, which would hit already struggling export-oriented countries such as Germany harder than others. But barring a severe downturn in the US – which is unlikely – we would not expect a eurozone recession to follow. In a similar vein, potentially more Fed rate cuts are unlikely to trigger more ECB cuts than in our base case. Prior to the recent market volatility, our view was already more dovish than the market in expecting three more rate cuts by the ECB this year. The increased downside risks to the outlook rather supports our view that the ECB will cut at consecutive meetings from September onwards.