US - High inflation is good for Trump

There is usually a slowdown in GDP growth in the quarters preceding elections, predominantly driven by slower private investment. After the election, the recovery is rapid, and partly accelerated by increased government expenditures. When inflation is high, the Republican candidate is more likely to win. Higher inflation implies the Federal Reserve is more often in a tightening cycle when a Republican enters the office, leading to amplification and lengthening of the growth slowdown and poorer stock market performance.

The first debate of the 2024 presidential election will take place tomorrow, a great occasion to kick off our coverage of the US election. We will have a lot to say about the implications of the US presidential election over the coming months, as we continue to think a potential re-election of Trump poses the biggest risk to the economic outlook, given his proposals for massive, large-scale import tariffs. But we start off with a much simpler question of a historical nature: how does the US economy typically behave around presidential elections? Elections induce significant policy uncertainty, which impacts the decision-making process of firms and people. After the elections, this uncertainty is partially resolved, and the outcome may either boost or lower confidence in the economy. In this piece we analyse the US economy around Presidential election years going back to 1960. This sample of sixteen election cycles allows us to pin down cyclical patterns in, amongst other, growth and monetary policy. This is the first time since the 19th century that both candidates have had a term as president. This suggests that a head-to-head comparison of the economic outcomes would be in order, were it not for the massive distortions of the covid pandemic in both tenures. We can, however, say something about the differences in the cyclicality of the economy depending on which party won the election over the years.

Growth is dampened before the election

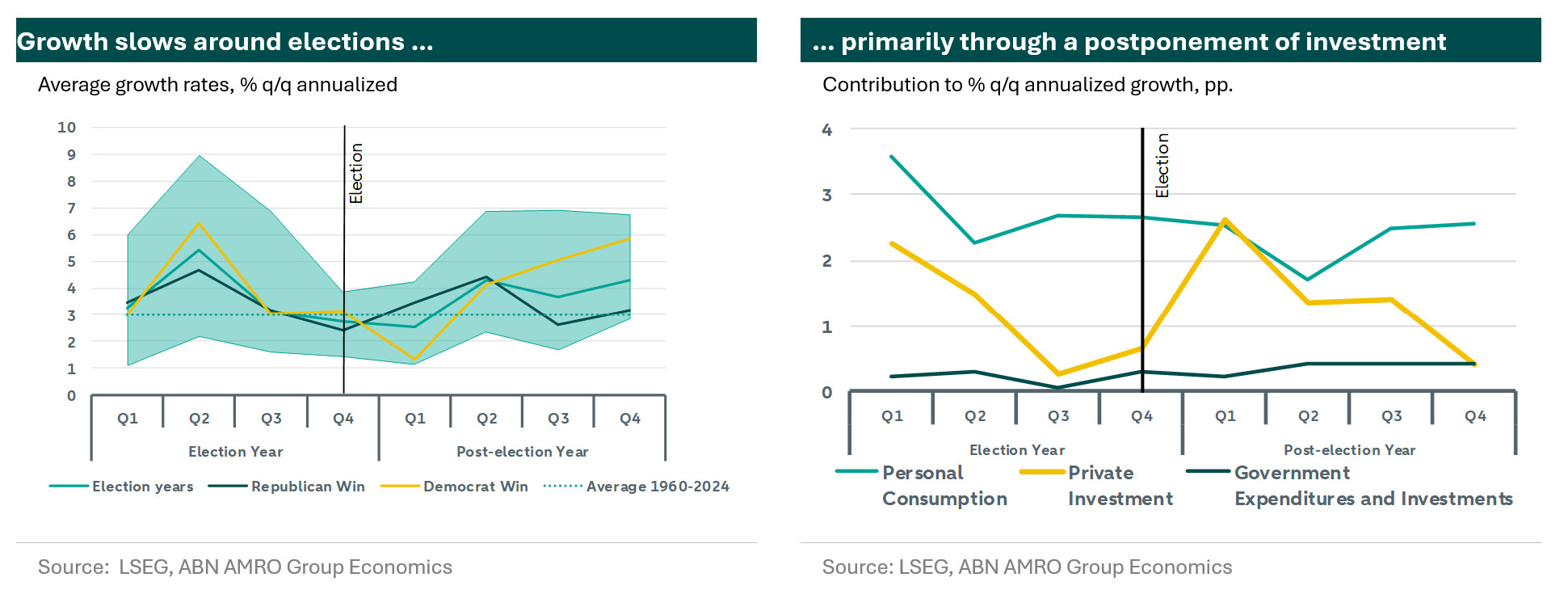

GDP growth has historically been subpar in election quarters(1). The left chart shows the average annualized quarterly growth around the election, where the election itself takes place in Q4 of the election year. The data shows that growth around election cycles is typically above the long-term average, but that there is a distinct dip in the quarter before - and of - the election. The shaded region represents the range of outcomes based on the 20-80% percentiles across election cycles. The variability across cycles is naturally substantial, but a seemingly effective predictor of variability, particularly post-election, is whether the winner is Democrat or Republican. Growth dips substantially more in the election quarter when the Democrat candidate wins, but subsequently recovers far more quickly as well. These patterns also hold around the elections where either a Democrat or Republican president is re-elected.

Why does growth slow around elections? GDP’s building blocks reveal that the slowdown is almost exclusively a private investment story, consistent with an increase in policy uncertainty and a delay in investment until the policy direction has become clear. Investment strongly rebounds in the first quarter of the new presidency, with overall investment growth over these two-year periods ultimately at least in line with non-election periods, if not higher. A further small boost comes from increased government expenditure, which grow strongly following the election, but have an overall limited contribution to GDP. The sensitivity of personal consumption to elections is smallest.

Fed policy the main driver of post-election growth difference

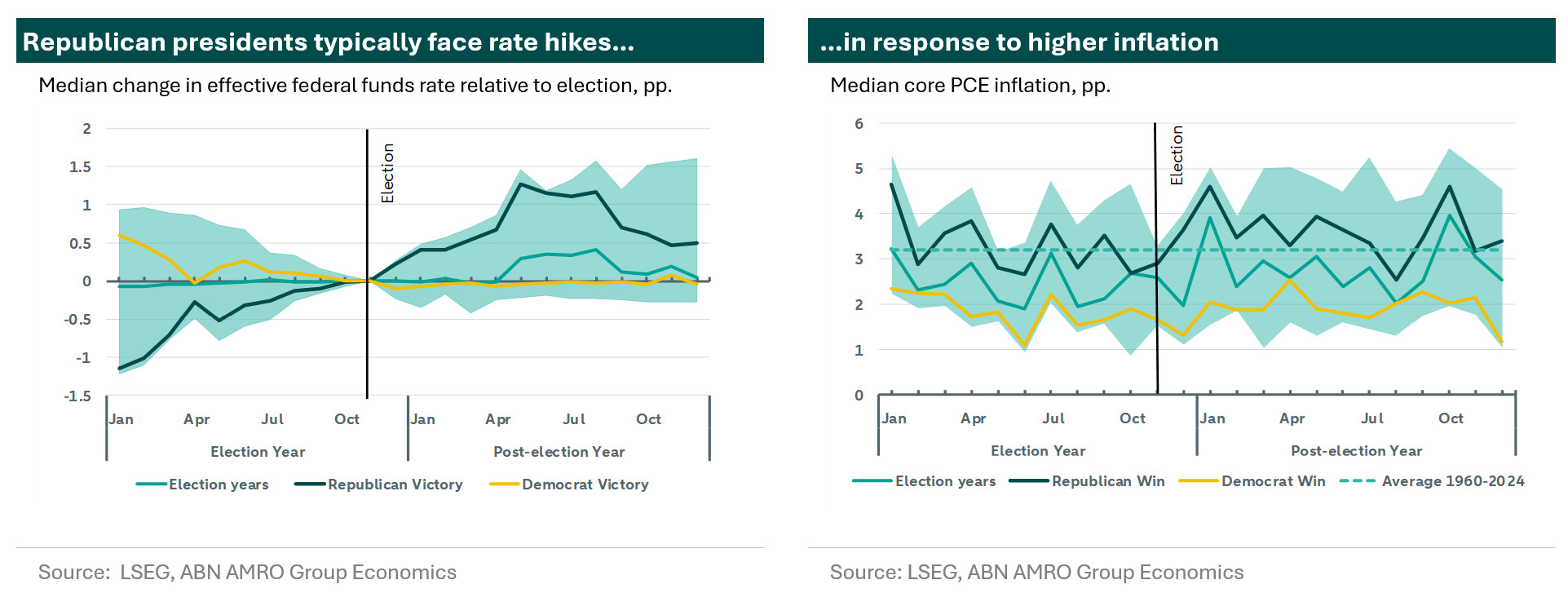

The median change in effective fed funds rate around elections shows no sign of systematic hiking or easing around elections. The shaded region shows that, in any given cycle, while rates have come up and down before elections, they’ve very rarely come down following elections (an easing cycle following this year’s election is likely to change that). Moreover, there is a clear difference in policy around Republican and Democrat victories. The typical Republican victory occurred in the midst of a hiking cycle, with rates being lower before the election and higher after. Importantly, this overall trend is driven by the cycles where the incumbent president was a Democrat, who therefore faced the initial tightening. The typical Democrat victory occurred in a more stable period where rates may have come down recently, but then stay steady afterwards.

Looking at annualized monthly core PCE inflation around elections, the hiking cycles around Republican victories are evidently warranted, as the average level of core PCE inflation has been substantially above the level around a Democrat victory, and indeed above the target rate of 2%. While we present no evidence of causality, all but one Republican win occurred in a period where inflation was above target. Indeed, of the 7 out of 10 elections since 1960 when core PCE inflation was above target were Republican victories, versus 1 out of 6 in elections where inflation was below target. Polls tend to show voters trust Republicans more with the economy, potentially offering an explanation for this correlation. The current elevated level is therefore seemingly an advantage for Trump.

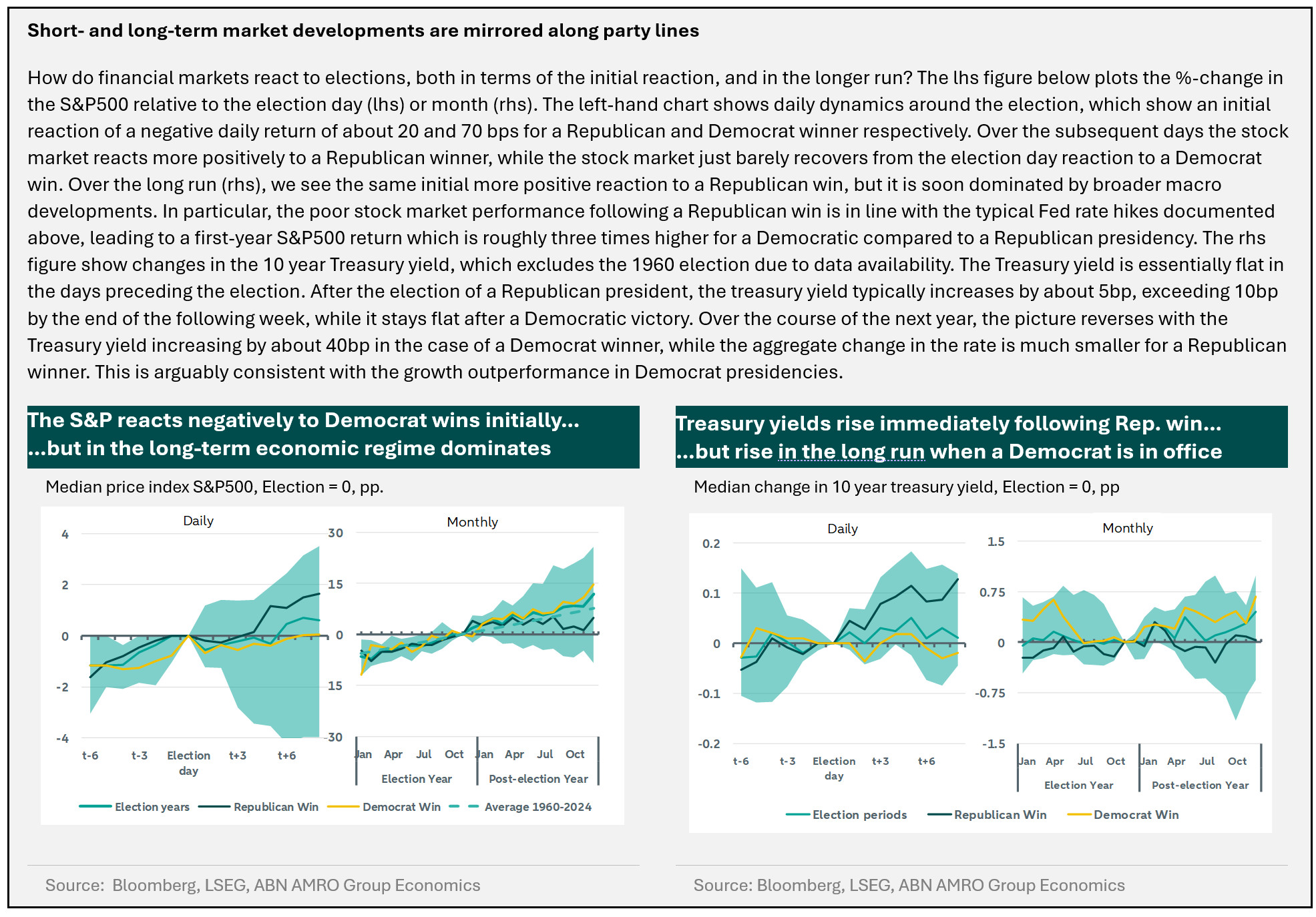

The higher level of inflation when a Republican enters office has a significant impact on the direct comparison of economic outcomes under the two parties’ rule. Indeed, the hiking cycle that is typical under a Republican president is also the likely driver of the slower post-election recovery in GDP growth. While we see no impact on the unemployment rate, we do observe a large difference in stock market performance, with an average annual return of over 13% in the two years around a Democrat victory, compared to less than 5% around a Republican victory. A large part of the outperformance after a Democrat presidency is probably explained by the difference in Fed policy.

Summing up, these historical patterns tell us that, with policy uncertainty as high as ever, slow-down in growth, particularly stemming from weaker investment is on the cards. This is consistent with our own view of below-trend growth in the second half of this year. Should this slowdown arise, it is important to interpret the numbers not just in terms of restrictive monetary policy, but also the uncertainty stemming from the election cycle. Second, what is also clear is that the Fed hasn’t been afraid to change rates forcefully when necessary, both before and after elections. We therefore continue to see no impediment to the Fed to start cutting rates later this year.

(1) In the analysis on growth, we exclude the 2020 election cycle due to the large outliers in GDP growth in Q2 and Q3 of 2020.