ESG Strategist - Climate disasters to exacerbate European fiscal deficits

Global warming is resulting in a rising number of climate and weather-related disasters. Although annual data is volatile, the costs of these disasters as a share of GDP are on a rising trend and expected to continue increasing during the coming years, even in a favourable 1.5°C global warming climate scenario where the targets of the Paris Agreement are met. In a previous research note ‘Which EU countries will suffer the most from extreme climate disasters?’ [1] we focused on the economic impact of climate and weather-related disasters in the EU at an individual country level under various scenarios of global warming. In this note we look more in depth at the impact on the public finances for a number of EU countries, namely their debt ratio levels, the impact on sovereign yields, and, ultimately, on their sovereign ratings.

Climate change is causing more frequent and severe weather disasters like storms, floods, droughts and wildfires

These disasters cause major economic damage, often partly insured, affecting buildings, livestock, resources, and infrastructure

Governments often provide aid for uninsured losses, replacing assets and repairing infrastructure

Climate disasters can also indirectly affect government finances by lowering GDP growth, tax income, and increasing financial risks

Uninsured costs from climate disasters are currently highest in Southern and Central-Eastern EU, but may shift to Western EU with higher temperature rises

Governments deficits and debt levels are affected by uninsured climate disasters and existing debt levels, in a non-linear way

Increased climate-related expenses are expected to exacerbate existing fiscal deficits in Europe, leading to higher government bond yields due to rising risk premiums

Future climate events will increasingly strain government finances, emphasizing the need for proactive fiscal and climate strategies to manage rising costs and avoid prolonged imbalances

Moody’s assessments indicate minimal impact of climate events on the credit ratings of Germany, Portugal and Spain

Sovereign ratings in developed economies currently overlook physical climate risks, focussing instead on traditional economic fundamentals

Why are some governments more vulnerable than others?

The impact of climate disasters on government debt trajectories varies significantly among countries. This variation arises from differing risks associated with specific types of climate disasters. Data from the European Environment Agency and the European Commission's Joint Research Centre shows that between 2000 and 2020:

Floods were most frequent in Central Europe (primarily Romania, Italy, and France);

Storms predominantly affected Central and Southern Europe (notably France, Germany, Poland, and Italy);

Wildfires primarily impacted Southern Europe (especially Spain, Portugal, Greece, and Croatia);

In contrast, Northern EU countries (such as Sweden, Finland, Denmark) reported very few such hazards.

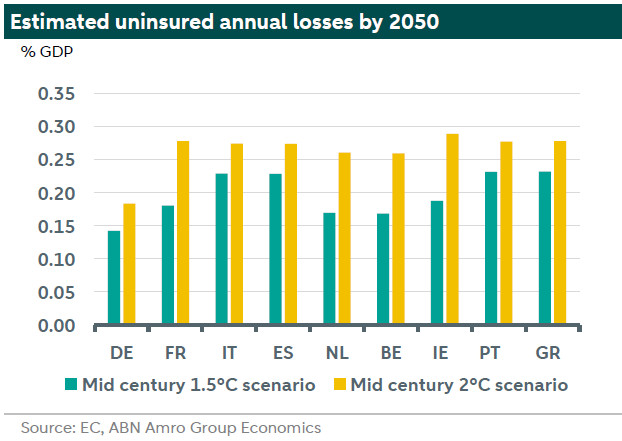

In line with the analysis by the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre (see ) we have considered three different scenarios for the medium term (2050). In the first scenario the global temperature rise is limited to 1.5°C. In this scenario the costs of climate disasters in the EU as a whole could be equal to around 0.2% GDP per year by 2050. In the second scenario global warming equals 1.75°C which would lead to a cost of around 0.25% of EU’s GDP per year. In the third scenario global warming equals 2°C. In this scenario the annual costs in the EU as a whole would rise to more than 0.3% GDP by mid-century. As some countries/regions will probably be hit harder than others the costs will be higher in some countries than others. Still, there is the caveat that when estimating the potential costs from climate and weather related disasters in the longer term, the outcome is surrounded by high uncertainty and the figures represent an underestimation (lower bound) of the expected impact, as they do not fully capture the effect of extreme events or the risks of passing the so-called tipping points [2]. In addition, the second round effects on the economy – for instance, via greater uncertainty and tighter financial conditions – are not fully captured.

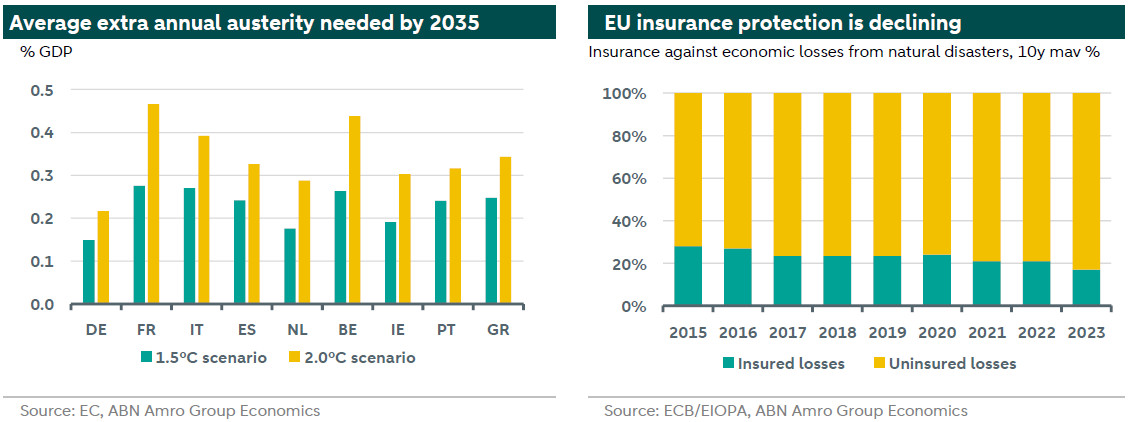

Insurance coverage also plays a vital role in determining how much damage will be covered by the private sector versus governments post-disaster. Although insurance coverage could decline when the number of climate disasters increases (see also our note (here), the current level of insurance coverage is relatively high in Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, France and Ireland and relatively low in Italy, Spain, Portugal and Greece. Considering all factors mentioned above, we have calculated that by 2050, the potential future costs of climate disasters are significantly higher for the Mediterranean countries (Italy, Spain, Portugal and Greece) compared to the other countries in the 1.5°C global warming scenario. However, were global warming to rise to 2.0°C the gap between the different countries narrows, as the costs would rise disproportionally in the Atlantic countries (France, Belgium, the Netherlands and Ireland) due to an increased risk of flooding episodes.

The impact of climate disasters will impair countries’ fiscal trajectories

In our assessment of government debt and fiscal trajectories—including potential impacts from climate disasters—we incorporated estimated annual uninsured disaster-related costs into primary budget balances through 2050. We have gradually phased in this damage, making it relatively moderate in the short-term and progressively enhancing the impact in the medium-term and towards 2050, as the frequency and severity of climate disasters is expected to rise over time. Moreover, we have assumed that GDP growth will be somewhat lower in the medium term, as the occurrence of climate disasters becomes more frequent and more severe. As a result economic growth and tax income might be reduced by a decline in labour productivity (for instance because people cannot travel to work), lower consumption and investment and disruptions to global trade flows.

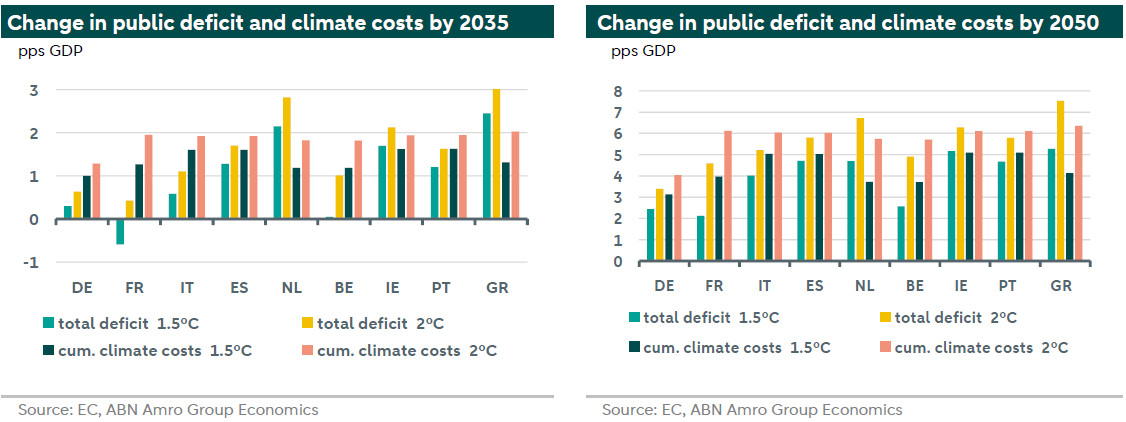

Below are our deficit estimates, including those climate events. It is important to note that in these deficit projections, we simply used the medium-term plans submitted by EU countries to the European Commission without making further adjustments. The purpose of this exercise is to purely examine the impact of acute physical risks on deficits, without accounting for other government spending developments. This is one reason why we observe a more limited impact on certain countries like France and Belgium, as their deficits are projected to return to the 3% target based on these plans. This assumption suggests a more optimistic outlook for these countries compared to other European peers, such as the Netherlands and Ireland, where deficits are expected to rise in current plans. Thus, these results might have a positive bias towards countries with elevated deficits in the medium term, as we take fiscal consolidation into account in the deficit forecasting model.

Nevertheless, the trend remains clearly negative for most European countries, as deficits are expected to rise by more than 2 percentage points during the next ten years for countries such as Greece and the Netherlands in the 1.5°C scenario. The effect on the deficits is even more dramatic if we look at a longer time horizon. Indeed, even in the 1.5°C scenario, the deficits are expected to triple and even quadruple for some countries by 2050 compared to 2035. Furthermore, those impact on deficits will push countries’ borrowing costs higher as discussed in the next section.

Alternatively, the calculations of the impact of the uninsured costs of climate disasters on the debt trajectories of the various countries under different scenarios for global warming can be used to estimate the amount of annual austerity that should be implemented by governments to compensate for the extra costs of climate disasters and prevent the debt ratio from rising due to these extra costs, keeping everything else the same. We have calculated these average extra annual austerity needs in the 1.5°C global warming scenario and the 2.0°C global warming scenario for the years up until 2035 (see graph below). As the graph shows these needs range from above 0.1% GDP in Germany in the 1.5°C global warming scenario to almost 0.5% in France in the 2.0°C global warming scenario.

Climate risks will push bond yields higher and add to countries’ deficit challenges

Acute physical risks will come on top of already numerous budget challenges and extra costs that European countries have to take on (i.e. defence, healthcare, pension costs). Thus, it is important to grasp how much climate change events will add to countries’ overall spending. Those risks can also feed through to higher borrowing costs for countries which means higher interest expenses, ultimately resulting in serious debt sustainability issues for countries with already elevated debt and deficit levels. Conversely, increased bond yields can exacerbate fiscal pressures by raising the cost of debt servicing.

The relationship between a country’s budget balance and its government bond yields (specifically long-term bond yields) can vary significantly across different countries within the eurozone and tends to be non-linear. Research often indicates that an increase in the fiscal deficit could lead to an increase in yields by anywhere from several basis points (bps) to potentially over 20bps or more. This is because larger deficits may raise concerns about a government's long-term debt sustainability, as more government bond issuance needs to be absorbed, and also tend to raise inflation expectations, which lead investors to request a higher risk premium to buy those government bonds. Of course, there are other key factors that affect countries’ borrowing cost such as market confidence, central bank actions, economic and political conditions.

In this section, we aim to isolate the effect of fiscal policy changes, specifically those driven by acute physical risks, on the 10-year bond yields of eurozone countries. To achieve this, we have used our deficit estimates from the previous section to translate them into changes in the 10-year bond yields, thereby incorporating the impact of acute physical risks on future borrowing costs. As mentioned earlier, various other factors influence the 10-year yield levels, so we control for these variables in our model (see Appendix C).

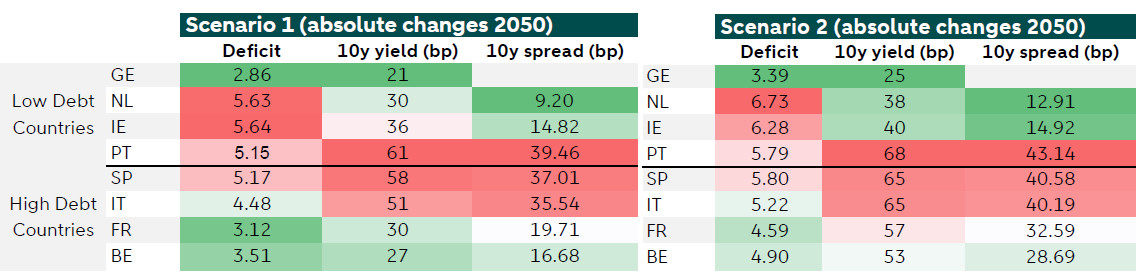

We have conducted a panel regression analysis to estimate the potential impact of a rising deficit on eurozone 10-year bond yields. While there isn't a precise figure that universally applies to all eurozone countries regarding how a 1% increase in the fiscal deficit would affect the 10-year yield, we have accounted for these differences using country fixed effects and have run regressions with different sample methodologies. Initially, we have categorized countries based on their sovereign ratings into core and peripheral groups. As expected, the results indicate that core countries were less affected by an increase in the deficit trajectory than peripheral countries. On average, a 1 percentage point increase in the deficit led to a 3.1 basis point increase in the 10-year yield for core countries, compared to 4.5 basis points for peripheral countries.

However, given recent fiscal developments within the eurozone and the increasing need for climate change investments in the coming decade, we decided to re-examine this issue by categorizing countries based on their fiscal profiles. Ultimately, countries with limited fiscal space for investment and spending should be more vulnerable to rising costs from climate disasters than those with sound fiscal positions. We have also excluded countries with small and/or illiquid bond markets. The results shows that countries with sound public finances experienced a 3.1 basis point rise in the 10-year bond yield for a 1 percentage point increase in the deficit, compared to a 5.3 basis point increase for countries with debt levels exceeding 100% and average deficits persistently above 3%. It is important to note that these estimates purely reflect the impact of deficits on the 10-year yield, holding all other economic and market variables constant in our model. In practice, the actual impact could be lower or higher, depending on the prevailing economic and financial environment.

One key factor that has significantly influenced long-term bond yields in Europe over the past decade is Quantitative Easing (QE). Studies have shown that QE has helped compress countries' term premiums over the years, potentially mitigating the effects of fiscal policy deterioration on government bond yields, as the ECB acted as a substantial buyer of bonds regardless of economic and fiscal policies conducted by the national governments. Therefore, we judge that it is essential to consider QE in this analysis due to its significant impact on long-term bond yields. We have included an interaction term between the fiscal deficit and QE (as a dummy variable), which proved to be statistically significant (see regression results in Appendix C).

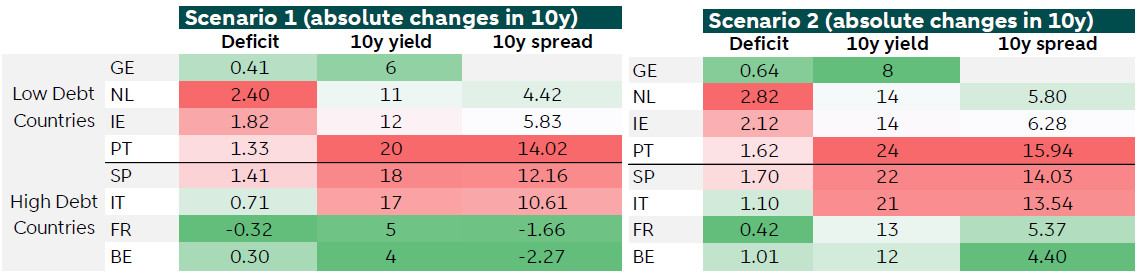

Based on these results, and incorporating our projections on countries’ deficit levels, the tables below suggest potential outcomes from the impact of acute physical risks on European government deficits, bond yields, and country spreads in the long term. We have calculated the results for two different climate scenarios, one assuming 1.5°C global warming (scenario 1) by mid-century and one assuming 2.0°C (scenario 2). In terms of deficit impact, the Netherlands, Ireland, Portugal, and Spain are the most affected across all scenarios. This aligns with our previous research (see here), which found that countries in the southern part of the EU are the most vulnerable to acute physical risks in the short-term but that these risks increasingly spread towards the Atlantic countries in the western part of the EU, due to their heightened vulnerability to acute flooding episodes in the longer term.

The results above illustrate the absolute changes expected from today through to 2050. A key takeaway from comparing the two scenarios is that while country spreads tend to remain quite similar, the impact of climate effects on deficits and 10-year bond yields is significantly greater in the 2.0°C scenario. In terms of borrowing costs, Spain and Portugal are the most affected countries, whereas Germany and France are the least impacted.

Below, we present another set of results, this time focusing on the 10-year horizon. The effects on countries’ deficits and 10-year bond yields are more subdued, which aligns with the view that climate change impacts will take time to be reflected in bond yield pricing and country spreads. The climate effects are expected to be more gradual initially, before accelerating in the medium term. In this context, short-term fiscal consolidation helps moderate the impact for countries like France and Belgium, while the Netherlands is currently projected to have a wider fiscal deficit based on the current government policy trajectory.

In conclusion, the fiscal impacts of climate-related events are expected to take time to be reflected in government bond yields, as the effects on deficits will initially be gradual. However, the accumulation of costs from these events could quickly accelerate if additional government spending becomes necessary or if larger-than-anticipated climate events occur earlier than projected. These climate impacts are likely to result in prolonged budgetary imbalances, putting countries' deficit and debt trajectories on an upward path for the coming decades. The frequency and heightened risk of natural disasters can lead to investors demanding higher risk premiums to the most exposed European countries, thereby raising bond yields (as shown in those results). In turn, this could result in higher government bond issuance to finance those rising deficits if no European solidarity framework is put in place (see the text in the Appendix A for more information about a European solidarity framework). This phenomenon is already evident, as seen in the recent example of Spain, where flooding in Valencia contributed to an increased deficit and led to a slight uptick in debt issuance this year.

Our results indicate that sovereign bond spreads are likely to widen following major climate disasters. Although, to a moderate extent given that the trend is for European government yields to rise more broadly based on rising costs from climate events. This could trigger a typical flight-to-quality towards countries like Germany or France, which experience more moderate deficit impacts from acute physical risks. However, the results also suggest that even countries with initially strong fiscal positions are not fully shielded from these climate events, as some are projected to be heavily exposed. Without transition or mitigation plans in place, these countries may find themselves on a negative fiscal trajectory moving forward. This analysis underscores the importance for these countries to establish such plans now in order to reduce future physical costs. Particularly as those countries have the fiscal space to do so now.

Sovereign ratings currently do not account for physical climate risks

Previous research, including our own recent publication, has consistently found that climate change does not significantly impact credit ratings in advanced economies. For example, an concluded that climate change vulnerability does not notably influence credit ratings in advanced economies, unlike in developing countries. Although climate resilience positively affects credit ratings across both developed and developing nations, its impact is nearly three times greater in emerging markets. Our study, using an ordered probit model, also found no significant relationship between climate-related variables and sovereign ratings.

As an example, we also examined Moody’s reports for Germany, Spain and Portugal to assess any changes both in their credit and ESG ratings. Following recent climate events. First, we compare Germany’s 2021 report, issued after devastating European floods, with the August 2024 report. While the most recent report acknowledges the increase in severity and frequency of extreme climate events like flooding and drought, the report published following the floods did not specifically mention these events. In both reports, Germany maintained a positive CIS-1 rating, which Moody’s attributes to “low exposure to environmental risks across all categories”. The agency considers that Germany’s “relatively high innovation capacity should help identify solutions” and that “the associated direct economic impact [from those type of climate risks] appear manageable”. Overall, it seems that Moody’s does not view current and future climate risks as a significant threat to Germany’s economic growth and its ability to repay public debt.

In analysing Portugal, we examined three reports: one from September 2017, following wildfires that claimed 66 lives, another from April 2022, and the latest from November 2024, after recent wildfires in northern Portugal. The 2017 report did not mention the wildfires or include any ESG considerations. By 2022, ESG factors were addressed, and Portugal received a CIS-3 rating, viewed as moderately negative. This score was attributed to "water scarcity" risks and frequent summer wildfires, with the 2017 events noted for the first time. The most recent report, following wildfires that resulted in at least nine fatalities, upgraded Portugal's ESG score to CIS-2. However, it states that "Portugal’s CIS-2 indicates that ESG considerations do not have a material impact on the credit rating," aligning with findings that ESG risks are often not reflected in credit ratings. Although the environmental score remained the same from 2022 to 2024, the report offers a more detailed account of Portugal's risks and opportunities. Moody’s identifies "physical risks caused by heat and water stress, wildfires, and sea level rise" as factors lowering the environmental score. Nonetheless, opportunities such as enhanced coastal protection, improved water retention systems, and better water management could bolster Portugal's future resilience.

Finally, regarding Spain, we were interested in determining whether the deadly floods in Valencia in November of the previous year had influenced Spain's credit rating or prompted any response from Moody's. Throughout 2024, the rating agency issued two credit updates, one in March and another in September. Based on these updates, we conclude that the floods did not impact Moody's assessment of the Spanish economy. In terms of ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) considerations, Spain received a CIS-2 score in both reports, with no changes in this section. Similarly to Portugal’s report, Moody’s states that “ESG considerations have no material impact on the current rating.” Therefore, it seems that Moody's does not view environmental risks as a threat to Spain's debt repayment capabilities or its economic fundamentals. Nonetheless, the agency notes that Spain is highly exposed to physical climate risks, particularly sea level rise, water and heat stress, and recurring wildfires.

In conclusion, both quantitative and qualitative analyses of credit rating reports and scores indicate that the sovereign ratings of developed economies do not appear to be influenced by a country’s ESG profile as of yet. The primary factors determining these ratings continue to be economic fundamentals, such as GDP per capita, real GDP growth, external debt, public debt levels, and the government budget balance. This may seem counterintuitive, given that the increasing frequency and severity of physical risks poses significant threats to a country’s economic fundamentals and results in a significant deterioration of government finances. Ignoring one will inevitably affect the other, as demonstrated by the analysis above on the impact of acute physical risks on a country’s deficit and debt levels. As such, even though we do not expect climate events to affect a sovereign rating in the short-term, we do expect the macroeconomic effects that result from those physical risks (e.g. an increase in a government’s debt ratio, among others) to affect the sovereign ratings over the medium- to long-term.

[2] Critical thresholds in a system that, when exceeded, can lead to a significant change in the state of the system, often with an understanding that the change is irreversible’, IPCC

Appendix A, B and C can be found in the full document