ESG Economist - Supply risks of transition commodities mount

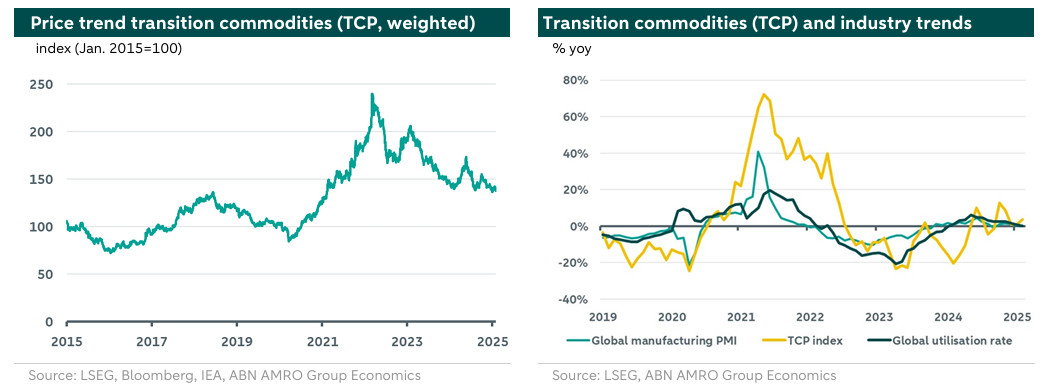

So far this year, the price index for transition commodities has risen by 10%, mainly due to the strong recovery of copper prices and some early signs of recovery in Chinese industrial activity.

So far this year, the price index for transition commodities has risen by 10%, mainly due to the strong recovery of copper prices and some early signs of recovery in Chinese industrial activity

In the longer term – at least until 2030 – the demand for transition materials is expected to grow annually

In the shorter term, the trade war has the potential to weaken industrial activity globally and thus have a negative impact on the demand for transition commodities and on their price

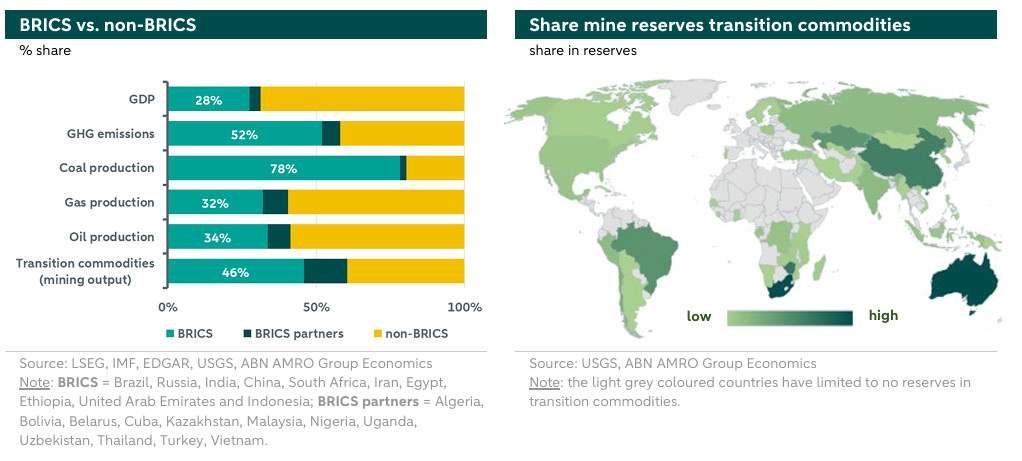

The availability of transition commodities remains a major concern; the BRICS bloc has a share of over 60% in the mining production of these raw materials

For the EU, this imbalance in the distribution of transition commodities is an obstacle for making these technologies, as the continent is not self-sufficient in many of these raw materials

The strong concentration of transition commodities in a limited number of countries only increases the pressure on the transition commodity markets, and with it the supply risks

The transition commodities needed to create low-carbon technologies have now acquired a prominent place in the energy transition. Without these raw materials, such as copper, nickel, cobalt and lithium, the transition to a low-carbon economy could become practically impossible. The demand for transition commodities has increased sharply in recent years. And there is a good chance that this will continue going forward. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), global growth in demand for these commodities will remain high until 2030.In this analysis, we look at the recent trend in the composite transition commodities price index and the driving force behind this trend. We will address the expectations of the demand for transition commodities in the coming years. We show how the price development influences the level of raw material costs for five low-carbon technologies. We will also discuss the availability of the transition commodities. This is not only relevant because the need for transition commodities remains high in all IEA-scenarios towards 2050, but also in view of the increased volatility in the geopolitical landscape.

Price trend transition commodities

After the outbreak of the corona pandemic and the subsequent sharp decline in economic activity, the price index for transition commodities weakened. This was followed by a recovery, partly due to a sharp decline in inventory levels and improved market sentiment due to the prospect of a post-corona recovery. The index then peaked at the beginning of Russia's invasion of Ukraine and fell sharply thereafter. In the period following this invasion, uncertainty in the markets for transition commodities has still not completely disappeared and volatility remains relatively high.

This year, the price index for transition raw materials has risen by 10%. As of mid-March 2025, the price index is still about 45% above the level at the low point of the corona crisis of March 2020, but still 52% below the peak level of March 2022. The strong recovery of the index is mainly due to the strong rise in copper prices. Copper has a relatively large share in the index and its price has risen by 13% this year. The increase was mainly due to the first signs of recovery in industrial activity in China, continued robust demand for the metal from China and the Chinese stimulus measures taken by the government. The latter is creating a positive sentiment in commodity markets.

The prices of many transition commodities are largely influenced by the trend in industrial activity. As soon as industrial activity decreases – and with it the demand for commodities – the price of transition commodities falls. When activity recovers, the price usually increases. This is shown in the upper right figure. Due to this causal relationship, commodity prices are often referred to as the pulse of economic activity. For the coming years – at least up to and including 2030 – the demand for transition commodities is expected to grow annually. This is evident from the scenarios of the International Energy Agency (IEA).

The IEA has compiled three future-oriented scenarios that reflect the growth in demand for metals and minerals up to and including 2050. These scenarios are, in order, the Net Zero Scenario (NZS, achieving net zero emissions by 2050), the Announced Pledges Scenario (APS, promises made are promises kept) and the Stated Policies Scenario (STEPS, which is the more conservative scenario based on announced policy). Regardless of which path or scenario is ultimately chosen, the growth in demand for metals and minerals will be strongest until 2030. The growth in the NZS is by far the strongest until 2030 because in this scenario, a strong focus will be placed on the use of clean technologies in the short term. This is much more the case than in the other scenarios. This results in a much faster increase in the demand for transition commodities. In the medium to long term, the growth in demand then weakens. This is most pronounced in the NZS scenario. In each scenario, the demand for and supply of transition commodities will not be too far out of line. However, the trade war has increased the likelihood that industrial activity in many countries will weaken. This will have a major impact on the demand for transition commodities and low-carbon technologies.

Transition commodities and low carbon technologies

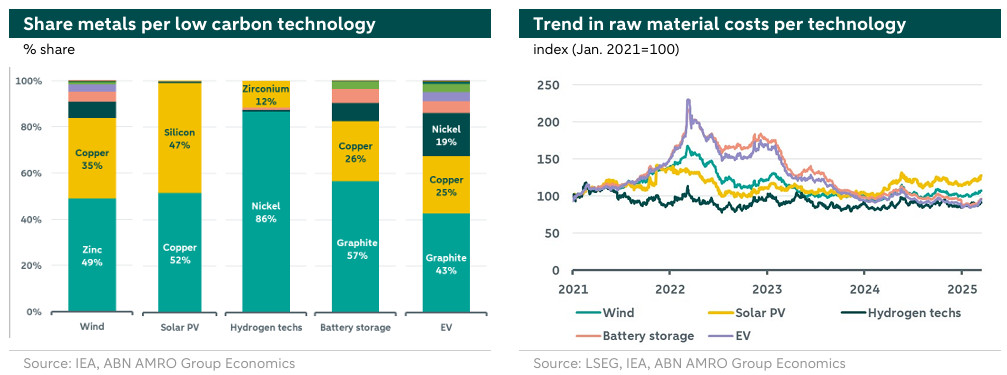

The energy transition is metal-intensive. Base metals – such as copper, nickel and zinc – are widely used and processed in low-carbon technologies. But the so-called ‘minor metals’ – such as silicon, graphite and cobalt – also play an essential role in the production process of these technologies.

The figure on the left below shows the distribution of the necessary transition raw materials per low-carbon technology. This distribution shows that copper is the most essential metal for the transition to a low-carbon economy. Copper is a necessary ingredient for almost every green technology, and the price trend of this metal therefore has a major impact on the cost of these technologies. But this does not take away from the fact that the other metals would be at least as important in their manufacture. For without the ‘minor metals’, it is not possible to eventually make the low-carbon technology.

According to many analysts, copper will remain an outperformer in 2025. Many expect the price of copper to rise further in 2025, perhaps even reaching new peak levels. In this scenario, the price of copper will drag the price index for transition commodities along in its rise, and with it the costs of making low-carbon technologies. However, in the current geopolitical context, it has become much more complex to be able to give a clear interpretation of the trend in many raw material prices. The policy uncertainty worldwide is currently too high and market trends are too volatile for this. In the long term, however, expectations for copper remain positive. In the Net Zero scenario, the demand for copper increases by 50% by 2040 compared to 2023, according to the IEA. The volumes of copper needed will remain by far the largest, but the expected growth rate of the demand for copper will remain in line with historical growth figures.

When we combine the required metals per low-carbon technology in a separate transition commodity price index per technology, it is particularly noticeable that the costs for battery storage and the EV remained relatively high in the period 2022-early 2023, mainly due to the increased price of graphite. The costs of the other technologies fell faster and in 2025 fluctuate for almost all technologies around the 2021 level. Only the costs of solar panels are slightly higher.

Availability transition commodities

The clean technologies that are needed on a large scale require a lot of raw materials. Because the extraction of many of the transition raw materials is concentrated in a few countries, they are of great strategic importance. If we look at the difference between the BRICS countries plus (which includes partner countries and totals 22 countries) and the countries that are not part of this group (175 countries), the impact of the BRICS block is significant. This block has become an important economic power (with a share of approximately 30% of global GDP) and that importance will only increase in the coming years.

It is also remarkable that a bloc of 22 countries with a 30% share of global GDP ultimately has a share of almost 60% of total greenhouse gas emissions. This indicates that the GHG intensity in the bloc is relatively high. The great importance of the entire bloc is also reflected in the trade of raw materials. The BRICS countries (including partner countries) have a share of over 40% in oil and gas production and a whopping 80% share in coal production. And finally, the bloc (including partner countries) has a share of over 60% in the mining of raw materials needed for the transition.

And it does not stop here. Other countries have applied to become members of BRICS. It is and remains a bloc to be reckoned with in international trade relations and has an important strategic asset with its commodity wealth. The high concentration of transition materials in a limited number of countries only increases the pressure on individual metal markets. For example, a coordinated approach to export restrictions by BRICS+ could pose significant risks to the availability of many transition commodities, but also critical metals that are vital for the energy transition, defence and other technological applications. This increases the economic vulnerability of Europe and also that of the United States, for example.

The original BRICS countries – Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa – are all countries which are rich in transition materials in terms of mining reserves. But the emphasis varies greatly from country to country. For example, South Africa has a high mine reserves share in total transition commodities because it has particularly rich reserves of chromium (especially important for the construction of nuclear facilities). The country has less reserves of other raw materials that are important for the transition. This does not apply to China, however. This country has a much more diversified range of mineral resources, making it the world's most important supplier of raw materials for the transition. Next to that, China has the largest manufacturing (processing) capacity for these materials in the world. In the non-BRICS block, Australia in particular has large mining reserves.

To conclude

A continuous production of clean technologies and a reliable supply of transition commodities is a prerequisite for a somewhat smoother path of the energy transition. As soon as the supply of these transition commodities cannot keep up with the growth in demand, this will cause bottlenecks in the supply chain and increases price. But this will also be the case as soon as the international availability of transition commodities decreases due to increasing geopolitical tensions. Such disruptions can further drive up the price of transition raw materials, increasing concerns about the affordability of the energy transition. For the EU, this is probably the biggest obstacle, as the continent is not very self-sufficient in many of these metal markets. Should the price of primary transition commodities rise sharply, this will encourage a further upscaling of recycling capacity and material efficiency. However, the risk of a weakening in economic activity due to the trade war seems increasingly likely, which means that a sharply rising price index for transition commodities is not immediately the most likely scenario. Decreasing economic and industrial activity has a direct impact on the demand for low-carbon technologies and thus for transition commodities. In times of economic weakness, moreover, business continuity becomes of greater importance over (green) investments, increasing the likelihood that the transition to a carbon-neutral economy will be delayed.