Are extreme weather events becoming ‘uninsurable’?

Insurance can reduce – though not eliminate – the economic effects of extreme weather events, as it helps to reduce uncertainty by pooling risk. However, the increase in the frequency and intensity of catastrophes will likely reduce the availability of insurance coverage in many locations and/or lead to sharply higher premiums. Indeed, evidence of such a scenario is already building and the situation will likely get worse.

Extreme weather events are becoming more frequent and more severe. This trend will like continue as global temperatures rise

Insurance can reduce – though not eliminate – the economic effects of these events, as it helps to reduce uncertainty by pooling risk, though insurance coverage is far from complete as it stands

In addition, the increase in the frequency of extreme weather events will likely reduce the availability of insurance coverage in many locations and/or lead to sharply higher premiums

Indeed, evidence of such a scenario is already building, especially with regards to home insurance, and the situation will likely get worse rather than better

Extreme weather events, such as powerful heat waves and devastating floods, are growing in frequency and severity, and this trend is likely to continue as global temperatures rise. Indeed warming of 2°C is estimated to lead to a fivefold increase in exposure to all types of natural hazards globally. Insurance can play an important role in reducing the economic fall-out, but there are signs that increasing (potential) losses are putting the sector under pressure. In this short note, we look into the question of whether climate catastrophes are becoming ‘uninsurable’.

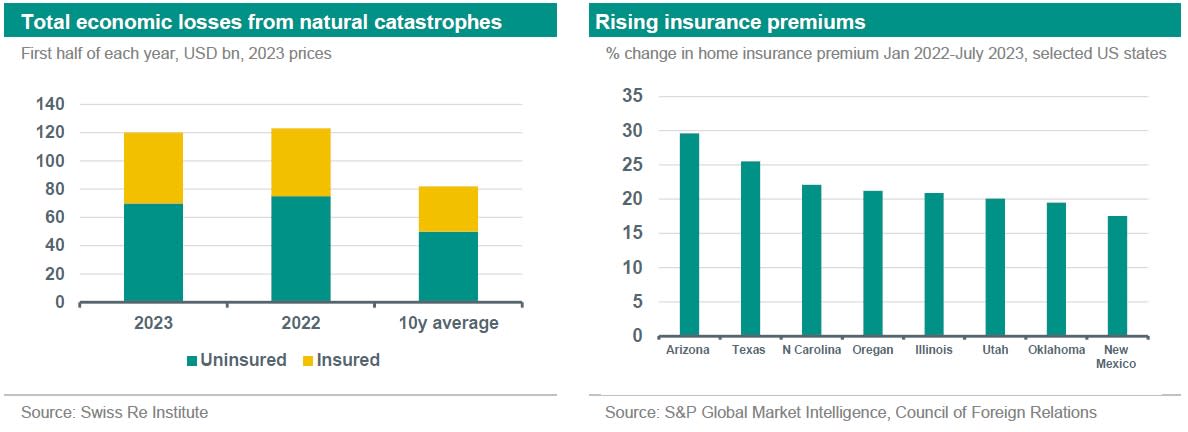

Rising losses from natural catastrophes

Total economic losses from natural catastrophes have been rising sharply over recent years. Data from Swiss Re, one of the world's leading providers of reinsurance and insurance, show that economic losses amounted to USD 120bn in the first half of this year. While this is slightly lower than in the first half of last year, it is up by 46% compared to the average losses over the last ten years. Of that amount, USD 50bn were insured losses, which is 42% of the total, showing that insurance coverage is far from complete even as it stands.

The economic losses from catastrophes is driven not only by the frequency and severity of these events, but also by the level of exposure. As Swiss Re notes ‘besides the impact of climate change, land use planning in more exposed coastal and riverine areas, and urban sprawl into the wilderness, generate a hard-to-revert combination of high value exposure in higher risk environments’.

The economics of ‘uninsurable’ risk

An insurance premium needs to cover expected losses, as well as expenses and profits. If that is widely not the case, the companies offering the insurance will go out of business eventually. In some cases, regulation can prevent premiums rising high enough. For instance, in California, regulators have prevented insurers from raising rates above a certain threshold. More generally, the expected loss could become so large that the insurance premium needed is unaffordable (and hence become ‘effectively uninsurable’). Perhaps most importantly, for a risk to be insurable it needs to be quantifiable. Climate change is not only making extreme weather events more frequent, but also the fall-out much more uncertain. When the likelihood and impact cannot be adequately quantified, it is impossible to calculate reasonable premiums. Finally, highly correlated risks are also uninsurable and losses related to extreme weather often have this characteristic. As an article by Milliman, the risk management consulting firm (see ), notes ‘the probability of me totalling my car is almost entirely unrelated to the probability of you totalling your car. In a wildfire-prone area where wildfires are becoming more common due to drought conditions, your probability of a total loss is closely related to your neighbour’s probability of a total loss’.

Impact on insurance markets

There are signs in certain geographies of higher premiums and reduced insurance coverage, especially for homes. For instance, home insurance premiums in the US have risen sharply over recent months. Since January of last year, thirty-one states have seen double-digit rate increases, while six saw increases of 20-30%, according to analysis by S&P and the Council of Foreign Relations (see chart above on the right). Meanwhile, some insurers have stepped away from offering insurance in certain regions. The Washington Post reported earlier this month that at least five large U.S. property insurers have told regulators that extreme weather patterns caused by climate change have led them to stop writing coverages in some regions and exclude protections from various weather events. In the Netherlands, consumers over recent years can no longer take out insurance against damage to their home due to subsidence (caused by drought?). The AFM (the country’s market conduct authority) notes that in 2016, four insurers still provided insurance for this risk. Similar trends are seen in many other countries. As well as growing catastrophe exposure, other reasons given for higher premiums/withdrawing coverage include soaring construction costs (which increase the replacement cost of a house) and a challenging reinsurance market. Indeed reinsurance (insurance for insurers) has also become much more expensive.

1% is the magic number

Looking forward, the severity and frequency of extreme weather events is likely to increase and therefore so are expected losses. However, obviously the risks and expected losses will differ significantly by location and hazard and hence general statements on the extent of the shift towards assets becoming uninsurable are not possible – though that is obviously the direction of travel. However, a specific example can help provide some colour of the mechanics at play. A recent study on the housing market in Australia by the Climate Council titled ‘Uninsurable Nation: Australia’s most climate-vulnerable places (see ) is interesting in this respect.

The report produced a ranking of the top 10 most at-risk electorates from climate change and extreme weather events by 2030. Riverine flooding was found to be by far the biggest risk, though bushfires and surface water flooding were other important hazards. The analysis uses a benchmark of 1% - properties that have projected annual damage costs equivalent to 1% or more of the property replacement cost – as being high risk. This category is defined as being ‘uninsurable’ as premiums would become unaffordable. This is consistent with the definition used by the US Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), which is seen as a benchmark. Meanwhile, the report also defines a medium risk category of 0.2-1%, which contains properties at risk of becoming underinsured (note that FEMA’s Moderate category – Becoming Uninsurable – is broader at 0.07-1%).

Overall, the research finds that by 2030, across Australia, 4% of properties would be in the high risk category, while a further 9% would reach the medium risk classification. It is also worth noting that there is considerable variation between districts. Taking the top 20 most at risk, the percent of properties in the high risk category varies between 7% and 27.4%, while the proportion in the high and medium categories varies from 11 to 54%. This points to very large variations in assets becoming uninsurable by location. However, recent developments have shown insurance companies have been less granular in their approach to withdrawing insurance. For instance, in the US, insurers have stopped offering insurance policies in whole states rather than particular districts, on some occasions, though this could be incidental.

Overall, the increase in the frequency of extreme weather events will likely reduce the availability of insurance coverage in many locations and/or lead to sharply higher premiums. Indeed, evidence of such a scenario is already building, especially with regards to home insurance, and the situation will likely get worse rather than better as global temperature rise, which will lead to an escalation of acute physical risks