ESG Economist - Which EU countries will suffer the most from extreme climate disasters?

Climate change and global warming is expected to result in a rising number of climate and weather-related disasters. Although annual data is volatile, the costs of these disasters related to the level of GDP seem to be on a rising trend and are expected to continue to increase during the coming years, even in a scenario where the targets of the Paris Agreement are met and the rise in global temperature is kept to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels (see for instance, the European Commission (EC) JRC PESETA IV Report (1) and the European Environment Agency (EEA) (2). Climate and weather-related disasters can have a significant impact on the economy and government finances, via various channels; both direct and indirect. In this research note we focus on the economic impact of climate and weather-related disasters in the EU and how vulnerable various EU countries/government are for the risk that the costs of these disasters could derail government finances during the next decades. We first focus on the direct short-term costs of climate and weather-related disasters and end by focusing on the longer-term consequences for economic growth. In a follow up note, we will look more in depth at the impact on the public finances for different EU countries and sovereign risk.

Climate change will result in a rising number of climate and weather-related disasters, such as temperature extremes, storms, floods, drought and wildfires.

These disasters are the acute physical risks from climate change, which can result in significant direct economic damage, such as the loss of buildings, livestock, natural resources and infrastructure, which in most instances is only partly insured.

A rising number of weather and climate-related disasters can also have a longer term impact on economic growth via reductions in capital stocks and productivity; most empirical studies find a negative impact on the level of GDP 10 years after the disaster, which tends to be more sizeable in low-income countries with low levels of insurance

Governments have spent substantial amounts on relief aid after uninsured losses due to climate and weather-related disasters, replacing damaged or lost assets of companies and households and repairing infrastructure …

… and government finances can also be affected indirectly by weather and climate disasters, via lower potential future GDP growth (meaning lower tax income), higher risk premia and the materialisation of contingent liabilities (through government guarantees for local governments and firms and support to distressed financial institutions)

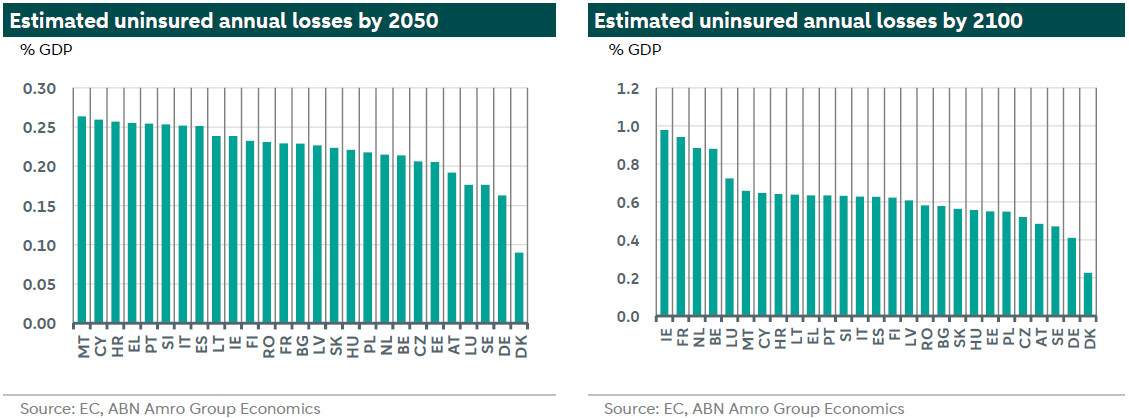

The risk of uninsured damage from acute physical climate disasters is highest in the Southern and Central-Eastern parts of the EU at the moment and lowest in the Northern part of the EU. In the medium to longer term and in scenarios of higher global temperature rises, these risks shift towards the Atlantic countries in the Western part of the EU.

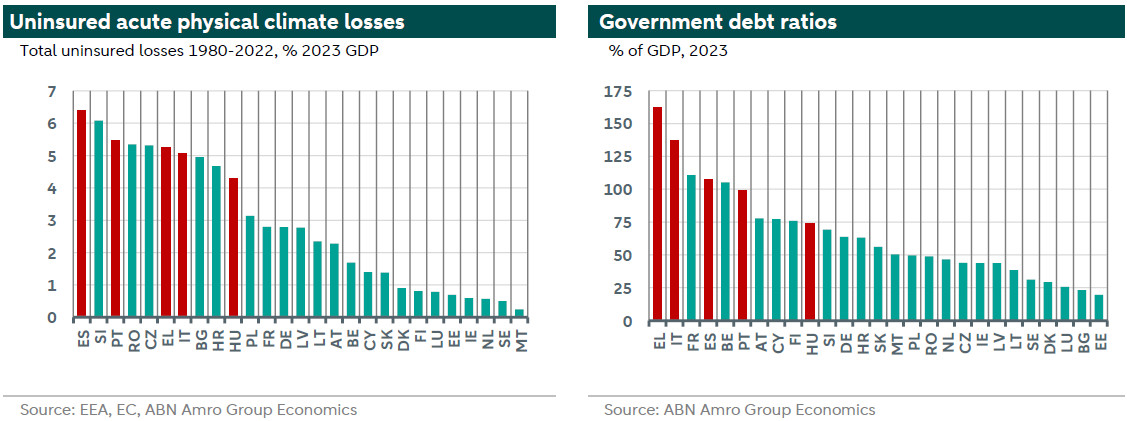

Zooming in at individual EU countries, we have ranked the EU countries/governments with a relatively high current debt ratio that will probably face the highest uninsured costs from climate and weather-related disasters in the coming years. These are Greece, Hungary, Italy, Portugal and Spain.

What and where are the main weather and climate related disasters in the EU?

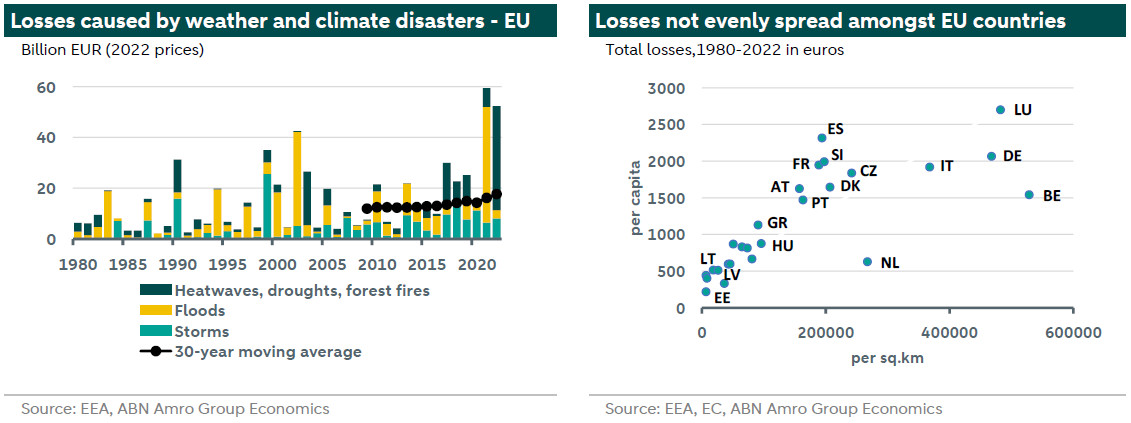

Data from the European Environment Agency (EEA, see ) show that during the period 1980-2022, an estimated total loss of EUR 650 billion (in 2022 prices and equal to 4% of 2022 GDP) was suffered due to climate and weather related disasters in the EU. Around 43 percent of the total was caused by hydrological hazards (predominantly floods), 29 percent by meteorological hazards (such as storms and hail) and the rest by climatological hazard, of which around 20% heat waves and around 8% droughts, forest fires and cold waves together. As the graph on the left below shows the annual incidence of climate and weather-related disasters can be volatile, but the trend clearly seems to be rising. Indeed, the 30-year moving average has risen from around EUR 12bn in 2010, to around EUR 18bn in 2022, with the total costs equal to 0.3% GDP in each of 2021 and 2022.

In a separate report The Fiscal Impact of Extreme Weather and Climate Events: Evidence for EU Countries (see ) the European Commission (EC) shows that breaking down the data into two periods of 1980-1999 versus 2000-2020 shows that the number of floods and storms each more than doubled during the years 2000-2020 compared to 1980-1999, whereas the number of episodes of extreme temperature and droughts has remained relatively stable during the two time periods. Moreover, during the period 2000-2020 floods have been most frequent in Central Europe (the most in Romania, Italy and France), storms in Central and Southern Europe (the most in France, Germany, Poland and Italy), wildfires in Southern Europe (most in Spain, Portugal, Greece and Croatia) and droughts in Central and Southern Europe (most in Italy, Bulgaria, Poland, Croatia, Portugal). Countries in the Northern part of the EU (such as Sweden, Finland, Denmark and the Baltic states) all have reported very few of the abovementioned hazards. As countries with a larger land area have a higher probability of being struck by climate and weather-related disasters, we have plotted the economic losses per square kilometre and per capita (graph below, right). It turns out that Luxembourg, Germany, Belgium and Italy are hit the hardest according to this measurement, whereas amongst the least hard-hit countries (the left/lower area of the graph) we find countries such as Sweden, the Baltics, Ireland and Finland.

In which countries are government finances the most vulnerable?

Government finances can be impacted by climate and weather-related hazards in several ways, both directly and indirectly. The direct costs for the government consist mostly of relief aid, replacing damaged or lost assets of companies and households and repairing critical infrastructure. On top of that economic growth and tax income can be reduced by a decline in labour productivity, lower consumption and investment and disruptions to global trade flows. Also, the government could suffer losses from the materialization of contingent liabilities such as government guarantees for firms, transfers to local governments and public support to distressed financial institutions. Finally, high vulnerability to acute physical climate risk could increase uncertainty and damage the creditworthiness of countries, raising the risk premium on government debt. Summing up, the impact of climate and weather-related hazards on the level of the government’s debt ratio can be driven by changes in the primary budget balance (i.e. the budget balance excluding interest payments), by changes in GPD growth and by changes in the level of interest rates. In this note we will discuss the direct impact on the government’s budget balance and the impact on longer-term economic growth. In a follow-up note we will elaborate on the longer-term government debt trajectories of various EU countries.

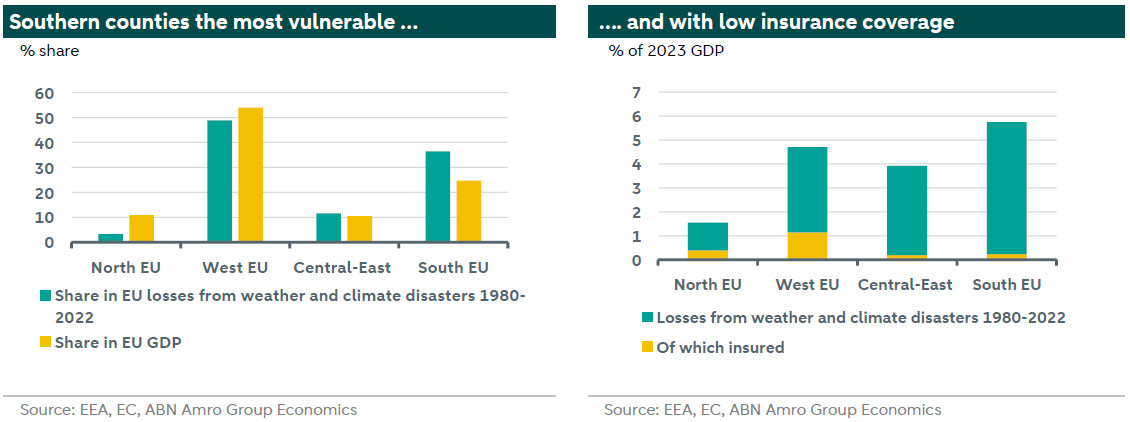

A government’s vulnerability to acute physical climate risk is determined by the potential future (uninsured) losses from climate and weather-related disasters and how high its government debt ratio is at occurrence. When considering the potential losses of climate related disasters, the EU is split into four main regions: Northern, Western, Central-Eastern and Southern (see explanation and details below the graphs). Countries in the Southern part of the EU are the most vulnerable to these acute physical risks related to climate change. Indeed, the region’s share in the total losses of these disasters during the period 1980-2022 is significantly higher than the region’s share in EU GDP, while only a small part of the costs related to acute physical climate risk is insured (see graphs above). This implies that in the Southern part of the EU a large part of these losses is uninsured while at the same time the government’s ability to finance these costs from domestic tax income is relatively low compared to the other EU-regions. In the Northern part of the EU this is the opposite, implying that governments can bear the uninsured losses of acute physical risk more easily.

To assess which individual country’s government finances seem to be the most vulnerable we have compared the past uninsured losses from climate disasters to the current level of the government debt ratio (see the two graphs above). Based on this ranking we can spot countries that are both in the top-10 of the countries with the highest uninsured losses and the countries with the highest debt ratios. These are: Spain, Portugal, Greece, Italy, and Hungary.

Future scenarios for the costs of climate-related hazards

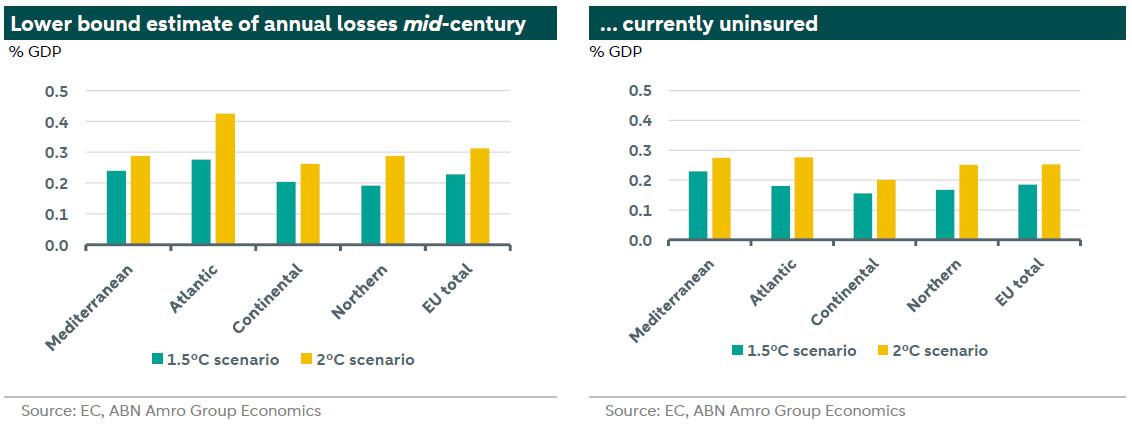

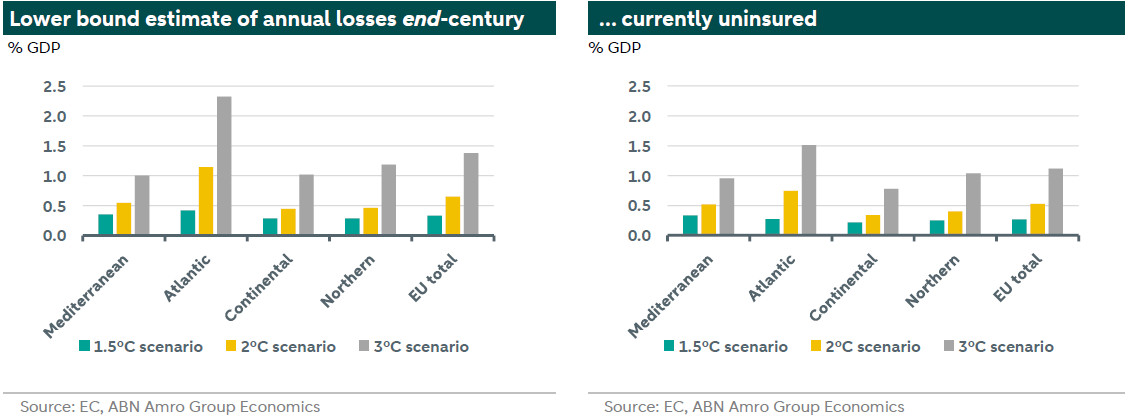

Estimating the potential costs for governments of future losses from acute physical climate disasters in the medium to longer term requires the use of scenarios for future climate change and global warming. The EC’s JRC Peseta IV report (link above) presents three scenarios. One in line with the Paris Agreement’s central aim to keep the global temperature rise until the end of this century limited to well below 2°C compared to pre-industrial levels (the 1.5°C scenario), one in which the global temperature rises by 2°C and one in which the global temperature rises by 3°C. Considering that the estimates are surrounded by uncertainty, big-picture estimates for broad regional trends seem to be the most adequate. That said, we have also estimated the potential impact at the individual country level.

When estimating the potential costs from climate and weather related disasters in the longer term, the EC mentions that the aggregated regional figures mask significant heterogeneity across countries and climate events and that the figures represent an underestimation (lower bound) of the expected impact, as they do not fully capture the effect of extreme events or the risks of passing so-called tipping points (‘critical thresholds in a system that, when exceeded, can lead to a significant change in the state of the system, often with an understanding that the change is irreversible’, IPCC). The purpose of the estimates is to ‘provide the general pattern of climate change impacts across the EU and the potential benefits of climate policy action’. According to the Peseta IV report in the scenario of a 3°C temperature rise the costs of acute climate disasters could rise to around 1.4% of GDP per year in the EU in total at around 2100. In the most favourable scenario where global warming remains limited to 1.5°C the costs could be limited to around 0.3% GDP per year at end-century (around 0.2% mid-century). In the scenario of 2°C global warming the annual losses would rise to around 0.7% GDP by the end of the century (around 0.3% mid-century -see graphs below).

The PESETA IV report uses a different regional break-down for EU countries than the EEA (see below). This main difference is that some of the Western and Northern European countries are labelled Atlantic in the PESETA IV report. Based on data and calculations presented in the PESETA IV report and the EC report The Fiscal Impact of Extreme Weather and Climate Events (link above), the following rough estimates can be made of the lower bound of future economic costs of climate and weather-related disasters in the various regions.

The calculations above indicate that in the medium (2050) and long (2100) term, the region that suffers the most losses will gradually shift towards the Atlantic countries due to the higher expected vulnerability of this area to flooding episodes. Although the Atlantic countries currently is the group with the highest insurance coverage for climate and weather-related disaster (around 40-50%), shifts in the risks surrounding these disasters can result in changes in the insurance coverage rate. Indeed, report by the EU’s EIOPA (see ) shows that insurance coverage declines when the probability of natural disasters increases. For instance, wildfires in California and Australia have resulted in widespread report of difficulties with insurance renewal according to EIOPA. See also our note (here).

Returning to the EC’s analysis of losses in the medium and longer term, more intense and frequent floods are behind the projected increase in disasters in countries in the Northern part of the EU (20-30% insurance coverage at the moment) and Continental regions (around 5-10% insurance coverage), whereas droughts are expected to be mostly responsible of the higher projected losses in Mediterranean countries (insurance coverage around 1-5%).

Zooming in at the individual country level, we have calculated lower bound estimates of the potential annual losses from climate and weather-related disasters in two plausible scenarios for global warming; one for 2050 (global warming between 1.5 and 2.0°C) and the other for 2100 (global warming between 2.0 and 2.5°C).

What are the longer-term consequences for economic growth?

Climate and weather-related disasters do not only result in short-term direct costs but can also result in economic damage in the longer- term. This can happen via direct and indirect channels that can impact both the supply and the demand side of the economy. On the supply side, climate disasters can significantly affect the agricultural sector, limit access to extractable natural resources and also cause severe damage to buildings, technology, and infrastructure (the destruction of physical capital). More generally, they can disrupt (domestic and global) supply of certain commodities such as food and energy, disrupt supply of labour (for instance, during heat waves and floods) and result in capital and technology losses as they divert investment away from innovation and towards reconstruction and replacement. On the demand side of the economy losses of wealth and financial assets can have an impact on private consumption and fixed investment, but also on global trade and exports. Moreover, uncertainty about potential future climate disasters can reduce fixed investments by companies and result in higher precautionary savings (reduced consumption) by households. Last but not least, the damage can be exacerbated via financial channels (access to bank credit, tightening of financial conditions and weakened resilience of the banking sector).

In general, the consensus view in economic literature is that the short-term impact of climate and weather-related disasters on economic growth is negative.

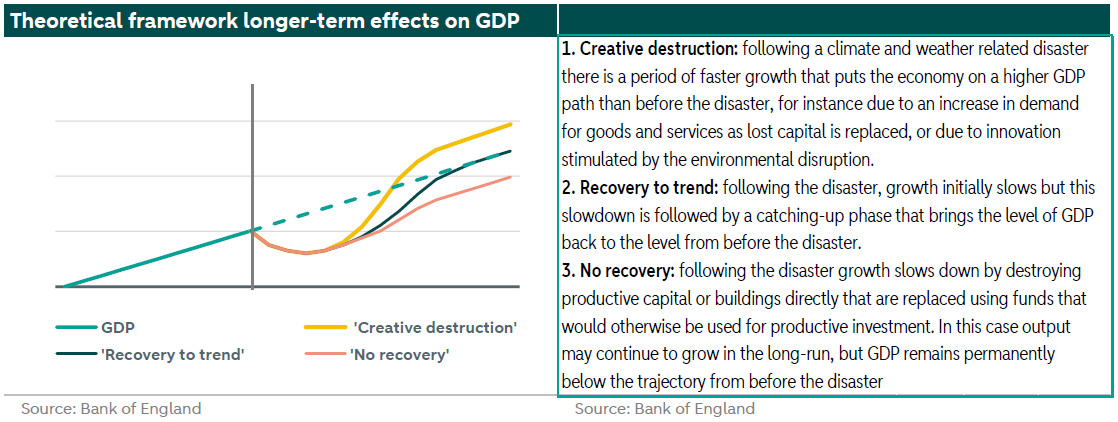

Over the medium to longer term these disasters can, however, enhance economic growth as investment for reconstruction is part of GDP (a flow) whereas the destruction of physical capital (a stock) is not. A report by the Bank of England (BoE - see ) gives an overview of the potential longer-term impact of climate and weather related disasters on the level of GDP. There are three different theories about the longer-term impact on GDP: 1. Creative destruction; 2. Recovery to trend; and 3. No recovery (see chart above). Besides the BoE the Bank for Reconstruction and Development/Worldbank (see ), the Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS – see ) and the Fed (see ) have published overviews of literature and empirical evidence about the longer-term impact of climate and weather-related disasters on the level of GDP. The empirical evidence is mixed, but most empirical studies support the third, ‘No-recovery’ hypotheses, implying that GDP permanently remains on a somewhat lower trajectory. A number of empirical studies find a cumulative loss in GDP per capita of roughly 0.5-1.0% ten years after a severe climate and weather-related disaster (above the 90th percentile of damages, which means average initial costs equal to 4.7% of GDP). The negative impact on GDP growth generally is found to be significantly larger in less developed countries with relatively low income per capital and low insurance coverage. Also, the longer-term impact of severe droughts and wild fires is found to be larger than the impact from floods or storms.

The Fed report also estimates the impact of disasters with a smaller initial damage of between the 80th and 90th percentile of damages. The initial costs of these climate and weather-related disasters on average is equal to around 1% of GDP. Damages of this magnitude have not been uncommon in Europe during the past few years. For example, the initial damage of the floodings in Germany and Belgium in July 2021 were equal to 0.9% GDP and 1.1% GDP, respectively. The initial damage of the extreme drought and heatwaves in Europe in the Summer of 2022 is estimated at around EUR 40bn by the EEA (equal to around 0.7% of the combined GDP of the countries that were hit the hardest). These two disasters on their own could have a longer-term impact on the level of GDP of around 0.1-0.2% 10 years from now, with the damage of the droughts and heatwaves probably larger than the damage of the floods in Germany and Belgium.