ESG Economist - Stronger reduction in heavy industry emissions remains crucial

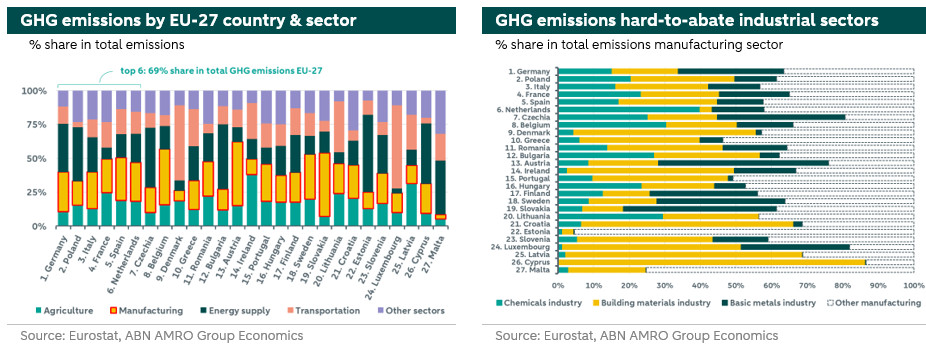

The share of emissions from industrial activity within total GHG emissions varies quite a bit by EU country. A large part of these emissions, 62% on average, is from hard-to-decarbonise industrial sectors, such as the building materials, base metals and the chemical industry. These industrial sectors are difficult to decarbonise due to technological challenges, high capital intensity and generally long investment cycles, although there are plenty of low carbon solutions. Decarbonising emission- and energy-intensive industries deserves special attention in the climate targets towards 2030 and beyond, as this is where the biggest climate gains can be made.

Industrial sectors, such as the construction materials industry (including the cement industry), base metal industry (including the steel industry) and the chemical industry, play an important role in meeting EU climate targets. These sectors each account for about 5% of total EU-27 greenhouse gas emissions, bringing the combined share to around 15%. The three sectors are among the most difficult to decarbonise and require significant investment to decarbonise processes. This is due to a combination of the technological complexity of business processes, high capital intensity and generally long investment cycles in these subsectors. In this analysis, we highlight the relevance of the three sectors within the EU-27 and indicate where within the EU the bottlenecks to a rapid transition to decarbonisation are greatest. In doing so, we additionally investigate how the three sectors influence the EU climate goals towards 2030.

Sectors with a difficult transition to low carbon

After the temporary upturn in EU-27 GHG emissions in 2021 (+5.6%), emissions fell by 0.8% on the continent in 2022. The aim is to maintain and accelerate a downward trend in GHG emission reductions in the coming years. In the post-Paris period (2017-2023), GHG emissions decreased more than in the 1990-2016 pre-Paris period.

For the EU-27 as a whole, the average difference was marginal (-1.0% annually in the pre Paris period vs -1.4% in the post-Paris period), but for countries like Estonia, Finland and the Netherlands the difference between the two periods averaged almost -5%. Among the six major emitters - which have a combined share of EU-27 GHG emissions of around 70% - five countries also show this trend. Poland is the only exception among these top six large emitters.

The share of industrial activity within total GHG emissions varies quite a bit from country to country. On average, industry has a 26% share in the EU-27 GHG emissions. For three countries this share is much higher: Austria, Slovakia (both 47% share of industry in GHG emissions) and Belgium (41%). For Denmark and Malta, the share is small (under 10%). Among the top six major emitters, the share hovers around the EU-27 average, except for Poland (with an 18% share). In this country, energy supply is the main source of greenhouse gas emissions.

Among heavy industrial sectors - such as chemicals, construction materials and basic metals - the share in relation to total industrial GHG emissions is high in the EU-27 at 62% on average. In only two countries the importance of heavy industry in GHG emissions is a lot less: Malta and Estonia. In Malta, the food industry has a large contribution to total industrial emissions, while in Estonia, the share of especially the manufacture of coke and refined petroleum products is significant within industrial GHG emissions. Moreover, from the relationship between the EU-27 countries, it is noticeable that the smaller countries generally experience relatively high levels of pollution from the construction materials industry (especially in Cyprus), while among the larger emitters here, an important role is played by the chemical industry, especially in the Netherlands.

Hard-to-abate

Large amounts of steel, cement and chemicals are consumed every year. Moreover, the steel, cement and chemicals sector will remain an important supplier of crucial materials for the foreseeable future. Making steel, cement and chemical products is not only very carbon-intensive, but the process for making these materials is also very difficult to decarbonise. In particular, a lot of heat is needed to make these materials. With that, it remains important to look for cost-effective ways to decarbonise production processes for these sectors.For each of the three hard to abate industrial sectors, there are plenty of solutions available to decarbonise processes. However, their implementation sometimes still faces obstacles, the main ones being the technological complexity of the business processes and the high capital intensity. Moreover, investment cycles within these sectors are often very long. This makes the whole investment decision very complex.

The building materials industry is an energy-intensive sector, as high temperatures often have to be reached to make the products (e.g. in kilns and in drying processes). For example, cement is made by heating ground limestone at high temperature with clay, shale, blast furnace slag and other materials. In the short term, the cement industry can work on increasing energy efficiency, switching to lower-carbon fuels and promoting material efficiency. But much emission reduction can also be achieved through feedstock substitution where low-carbon ingredients are used in the process. However, these are more complex interventions than introducing efficiency measures.

The production process in the chemical industry is also among one of the most polluting and energy- and resource-intensive processes. Many of the chemical industry's finished or semi-finished products find their way into other sectors and processes. In recent years, the chemical industry has invested heavily in cleaner production facilities, such as heat pumps and thermal storage. But the most relevant decarbonisation options for the chemical industry involve carbon storage, electrification and fuel substitution. However, it depends heavily on the chemical process to determine which technology is most suitable.

For the base metal industry, the main options to make the processes less carbon-intensive are electrification, carbon capture and storage and substituting the fossil fuels in the production process for the carbon-free variants (such as hydrogen, renewable energy). The steel industry is the subsector within the base metal industry with by far the highest energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions. In this subsector, switching to smelting scrap with electricity - instead of smelting iron ore with coking coal - can reduce emissions significantly. However, switching from a steel process based on iron ore and coking coal to one based on scrap and electricity does not happen overnight and may take many years.As the above list of decarbonisation options shows, the energy transition in these three hard-to-decarbonise sectors is taking place through a whole range of different low-carbon solutions. Because there is no single panacea, the transition takes a long time on balance.

Production and emissions trends at large emitters

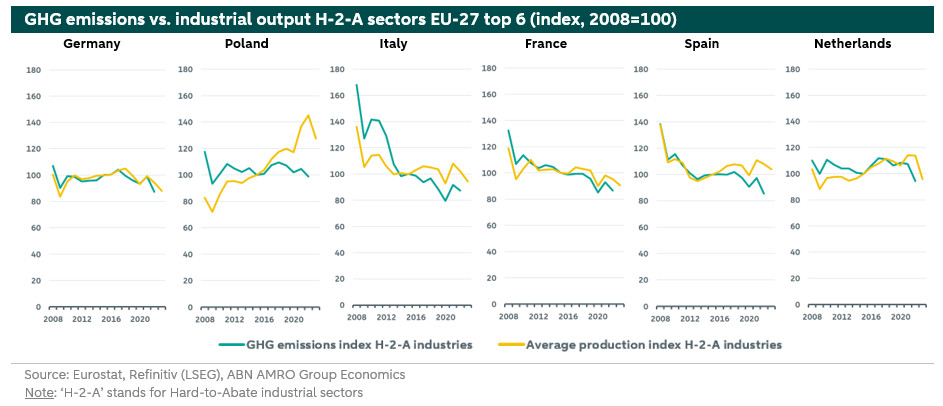

Each country within the EU-27 has its own challenges when it comes to reducing greenhouse gas emissions from heavy industry. It is often the economic structure, sector unique aspects in countries and regional factors that make the difference. In many cases, there is a strong link between heavy industry production and GHG emissions. This can also be seen in the figures below, where the top six major emitters are shown. Only in Poland is this link much less, but in a positive sense. Here, average production in the post-Paris period (2017-2023) rose sharply while GHG emissions decreased in the same period. In 2023, industrial production of hard-to-decarbonise sectors in Poland declined sharply. This is caused by weaker export demand and end-users' wait-and-see attitude towards purchasing durable industrial goods. Industrial production is also declining in the other EU countries in the figure below, often accompanied with lower levels of GHG emissions.

The decoupling between GHG production and emissions is still only partly visible among the top six emitters in the EU-27. At times, it is still a very short lived divergence between the two, nor has there been an immediate clear trend. In time, the relationship between production growth and emissions will diverge slightly more. This is triggered by the trend of decreasing energy intensity in countries over time and increased investment in decarbonisation technologies (such as energy efficiency, electrification, fuel substitution and deployment of renewables).

Impact of policies and climate targets

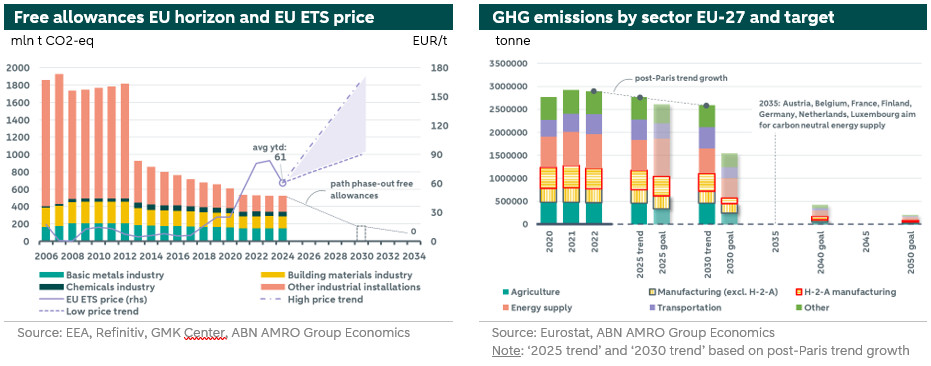

Under the EU Emissions Trading Scheme (EU ETS), Europe's largest emitters of greenhouse gases in the energy supply and industrial sectors must pay for every tonne of CO2 they emit. By reducing the number of free emission allowances - included within the system - every year, the EU can reduce corporate greenhouse gas emissions in an effort to meet climate targets towards 2030 and 2050. The annual reduction in free allowances provides upward pressure on the EU ETS auction price for an allowance, also known as the European Union Allowance (EUA) price. However, there are several other factors determining the trend in the EU ETS price,. All in all, it is a valuable tool for the EU in the fight against climate change and to encourage sustainability in business.

The cap on free allowances for 2013 was set on the basis of the average total amount of allowances issued annually in the period 2008-2012. After 2013, the number of free allowances continued to decrease for the entire EU with an annual linear reduction factor of 1.74% until 2020. In the period 2021-2024, the EU-wide emissions cap decreased annually with an increased annual linear reduction factor of 2.2%. Going forward, a reduction factor of 4.3% applies in the period 2024-2027 and a reduction factor of 4.4% from 2028 to 2030. Until the end of 2033, free allowances will be phased out at the same time as the gradual introduction of the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM). for more information on CBAM.

The trend in free allowances for industrial plants are shown in the left-hand figure on the next page, which distinguishes between hard-to-decarbonise industrial sectors and other industrial installations. The trend in free emissions described above is reflected also in the figure. Thereby, it is noticeable that the free allowances for large companies in the base metal, building material and chemical sectors are decreasing less than the free allowances for other industrial installations.

The European manufacturing sector is struggling economically. The European manufacturing purchasing managers' index (PMI) has been below 50 since July 2022, indicating a decline in overall industrial activity. Less economic activity and production also means less emissions and thus less demand for carbon allowances. This is also the case when the EU ETS price is relatively low, because then the financial capabilities of ETS companies is often weaker and this can dampen the demand for allowances.

Decarbonisation of emission- and energy-intensive industries deserves special attention in the climate goals towards 2030 and beyond, as this is where, on balance, the biggest climate gains can be made. And those overarching climate targets are not yet within reach, as shown in the right-hand figure. Achieving the set target towards 2030 will require more widespread deployment of the decarbonisation technologies with the most impact. It requires firm investments and stronger expansion of grid capacity for further electrification, simultaneously complemented by stimulating sustainable public policies. The efforts being made now are going to help make the transition to climate neutrality towards 2050 somewhat smooth and affordable. Currently, the outlook on the feasibility of the transition is still relatively unfavourable. Much remains to be done. Challenges - such as obstacles in the energy transition and the changing geopolitical context - still require a lot of attention and put a brake on the transition. But despite this, EU-27 heavy industry has made progress in reducing greenhouse gas emissions and saving energy. It is a trend that can be sustained with existing decarbonisation technologies in the coming years. The only thing now is to accelerate the reduction in emissions and further transition. Especially in the hard to abate sectors. More cooperation and coordination on the European continent is going to help in this regard to drive the transition to climate neutral.