ESG Economist - Carbon price for shipping below transition cost

International shipping is responsible for about 2% of the world's greenhouse gas emissions. This means it plays a part in reaching net-zero emissions, which would help limit global warming to 1.5 degrees. The shipping industry follows various regulations and targets from organizations like the International Maritime Organization (IMO), the Poseidon Principles, and the European Commission's Fit for 55 initiative. Shipping was included in the Emissions Trading System (ETS) in 2024. During the IMO's Marine Environment Protection Committee meeting (MEPC 83) from April 7-11, policy measures were discussed to meet the emissions targets set in the IMO's 2023 strategy. This publication focuses on the results of this meeting and what they mean for the maritime shipping industry.

In 2023, the International Maritime Organization (IMO) set a plan for reducing emissions…

…recently, the MEPC83 meeting outlined specific measures to achieve these goals.

However, there are obstacles that might hinder the implementation of the proposed measures.

In 2035, the cost of using alternative energy carriers for shipping is higher than the fines for not meeting emission standards.

Hence, shipping companies face a choice between paying fines or investing in new energy carriers and technologies that significantly reduce emissions.

In the upcoming years, paying fines will be cheaper than making the investments needed to reduce emissions.

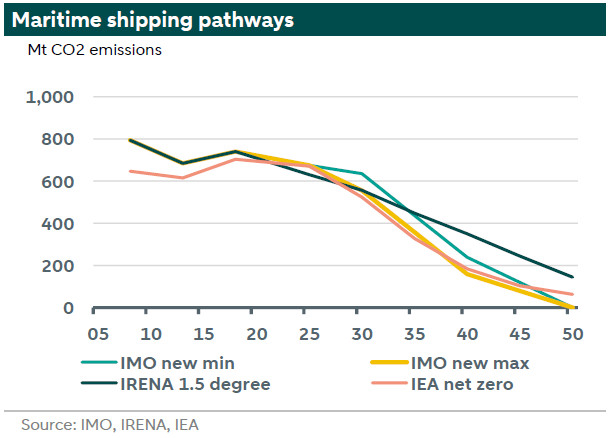

Maritime shipping pathways

In 2023, the International Maritime Organization (IMO) reviewed and updated its goals for reducing emissions. The IMO plans to cut the total yearly greenhouse gas emissions from international shipping by at least 20%, and striving for 30%, by 2030 compared to levels in 2008. By 2040, they aim for at least a 70% reduction, striving for 80%, and to achieve net-zero emissions by around 2050 (yellow and green lines in graph above).

The IMO's strategy is almost as ambitious as the International Energy Agency's net-zero pathway (orange line on the chart on the previous page) and is even more ambitious than the IRENA 1.5-degree pathway (dark line). To reach these ambitious goals, the IMO expects that technical innovations and the global rollout of technologies, fuels, and energy sources with zero or near-zero greenhouse gas emissions will be crucial (see more ).

MEPC83 results

On April 7th to 11th, the Marine Environment Protection Committee (MEPC) met for its 83rd session. The MECP addresses environmental issues under the IMO’s remit. In the latest session, the Committee negotiated the policy measures associated with the 2023 targets set in the IMO GHG strategy. It approved mandatory emissions limits and GHG pricing across the sector. It outlined a set of “mid-term measures” aimed at reducing emissions consisting of a new fuel standard for ships and a global pricing mechanism for emissions.

Under the draft regulations, ships will be required to comply with:

Global fuel standard: ships must reduce, over time, their annual greenhouse gas fuel intensity (GFI) – that is, how much GHG is emitted for each unit of energy used. This also includes electricity delivered to the ship, wind propulsion and solar power. This is calculated using a well-to-wake approach.

Global economic measure: ships emitting above GFI thresholds will have to acquire remedial units to balance its deficit emissions, while those using zero or near-zero GHG technologies will be eligible for financial rewards.

The amendments are due for adoption at an extraordinary MEPC session in October 2025. Adoption requires acceptance by two-thirds of the parties representing at least 50% of the gross tonnage of the world’s merchant fleet. If they are adopted, they will enter into force on 1 March 2027. They will then become mandatory for large ocean-going ships over 5,000 gross tonnage, which emit 85% of the total CO2 emissions from international shipping.

Short term measures

The International Maritime Organization (IMO) has introduced measures to help ships become more energy efficient and reduce their carbon emissions by at least 40% by the year 2030, compared to what they were in 2008. These measures include:

EEXI (Energy Efficiency Existing Ship Index): This is a tool designed to improve the technical performance of ships that are already in use.

CII (Carbon Intensity Indicator): This applies to all ships and measures how much carbon they emit. There are several ways to reduce carbon emissions, such as:- Optimizing speed, - Planning routes according to weather conditions, - Arriving at destinations just in time, - Optimizing ballast (the weight added to stabilize the ship)

The review of these measures is done in two phases. The first phase, completed by the Marine Environment Protection Committee (MEPC) in its 83rd meeting, looked at any gaps or challenges in these measures. No issues were found with the EEXI. The second phase of the review will start on January 1, 2026, and involve intersessional and Correspondence Groups. This phase is expected to finish by spring 2027.

The plan is not just to cut down on carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions but also to reduce other harmful emissions like methane, nitrous oxide (N2O), nitrogen oxides (NOx), and aerosols like black carbon. The Marine Environment Protection Committee (MEPC) in its 83rd meeting finalized guidelines for testing and measuring emissions of methane (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N2O) from ship engines. It is expected that these guidelines will be accepted under the European Union Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) and FuelEU Maritime regulations.

On board carbon capture and storage

Along with efforts to cut emissions, the Marine Environment Protection Committee (MEPC) has approved a plan to create rules for using onboard carbon capture and storage (OCCS) systems. This plan will cover both aspects related to ships and land, ensuring that OCCS fits into current and future regulations like the Energy Efficiency Design Index (EEDI). The goal is to complete this work by 2028.

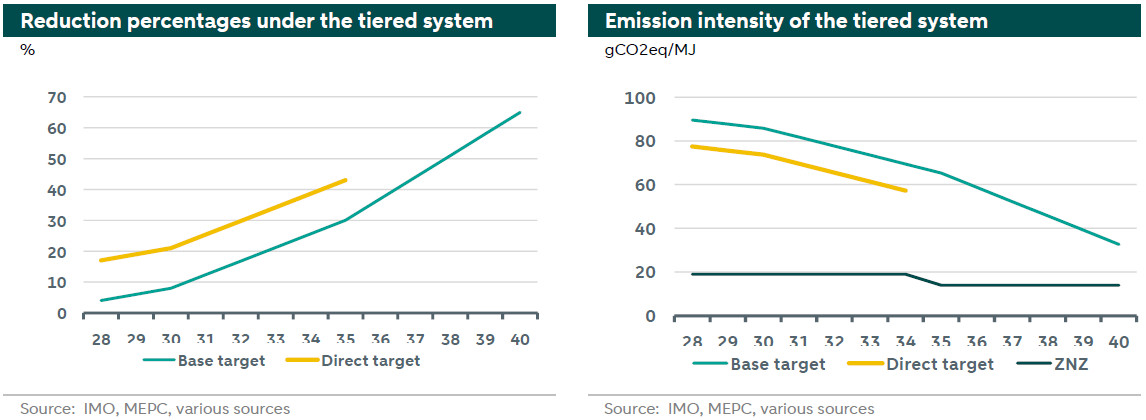

Fuel intensity targets

The Marine Environment Protection Committee (MEPC) plans to gradually tighten rules on how efficiently ships use fuel to perform its task (fuel intensity), considering everything from fuel production to when the ship uses it ("well to wake"). Starting in 2028 if the measures are adopted, ships will need to meet new reduction targets compared to their 2008 baseline of 93.3 grams of CO2 equivalent per megajoule (gCO2eq/MJ). There will be two levels of targets: a Base Target and a stricter Direct Compliance Target.

Initially, the Base Target will require a 4% reduction, and the Direct Compliance Target will require a 17% reduction. These targets will increase each year, aiming for a 30% Base Target and a 43% Direct Compliance Target by 2035. The rules include yearly reduction factors up to 2035. By 2040, the Base Target is set to reach 65% (see chart below on the left). The targets for 2036-2040 will be set by January 1, 2032.

The graph below on the right shows how these percentages affect emission intensity, measured in gCO2eq/MJ. This is compared to the emission intensity of fuels or technologies that have Near Zero Greenhouse Gas emissions (ZNZ). Initially, any fuel with emissions below 19.0 gCO2eq/MJ will be considered ZNZ and eligible for financial rewards until December 31, 2034. After January 1, 2035, this threshold will lower to 14.0 gCO2eq/MJ. Currently, only a few fuels have emissions below 19.0 gCO2eq/MJ. Some of these alternative fuels are mentioned in the chart on the next page on the marginal abatement costs. Using fuels and technologies with Near Zero Greenhouse gas emissions have the benefit of receiving financial rewards to partly compensate for the high costs.

What happens if ships are non-compliant?

If approved, ships that do not meet the emission reduction standard as set by the MEPC 83 will have to pay fees based on a tiered system. If a ship exceeds the basic emissions limit, known as 'Tier 2', it will be charged USD 380 for each tonne of CO2 it emits beyond this limit. Ships that meet the basic limit but still exceed another stricter target, called 'Tier 1', will pay USD 100 per tonne for their excess emissions. Ships can balance their extra emissions by using surplus emissions units from other ships, using their own banked surplus units, or by contributing to the IMO Net-Zero Fund to get remedial units. Ships that emit less than required can earn surplus units.

The greenhouse gas emissions from different fuel types will be calculated using the IMO’s guidelines, which will either use a default emissions factor or an actual, more accurate emissions factor.

The IMO Net-Zero Fund will collect money from emission penalties. This money will be used to reward ships that emit less, support innovation and infrastructure in developing countries, help train and build capacity to support the IMO’s greenhouse gas strategy, and reduce negative impacts on vulnerable countries like small island states and least developed countries.

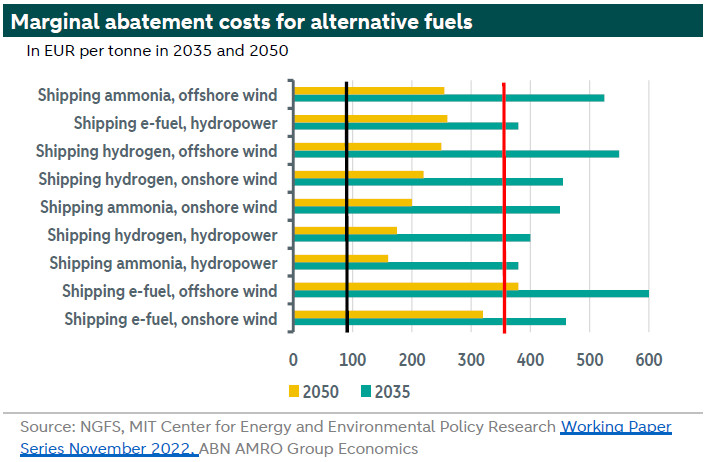

Compliance depends on the price of alternative energy carrier or technology

In 2023, the IMO set ambitious goals to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The measures mentioned above focus on reducing emissions throughout the entire process, from fuel production to its use on ships. If agreed upon at the special MEPC meeting in October 2025, these measures will be quite challenging to implement due to various obstacles.

One major challenge is deciding which future energy carriers to use, as it's likely there will be several options instead of just one. Many alternative fuels have lower energy compared to the fuels currently used in shipping. This means ships would need more space to store fuel and might need modifications to handle the extra weight and ensure safety. Engines would also need adjustments. Ships typically last about 25 years, so there's a risk of them becoming outdated before their lifespan ends. Even if the alternative fuel is chosen, there should be enough production to meet demands.

The cost of reducing emissions with these alternative fuels is currently high. The chart below shows these costs for different alternative fuels in 2035 and 2050. The red line represents the cost per tonne in euros if ships don't meet the basic emissions reduction target (Tier 2). The black line shows the cost if ships meet the basic target but not the stricter one (Tier 1). In 2035, all costs are above the red line, meaning it's cheaper to pay for not meeting the target than to buy alternative fuels. By 2050, most costs are below the red line, making it more cost-effective for ships to meet at least the basic target. These costs keep changing and depend on the total emissions throughout the energy's lifecycle and production costs.

The cost of reducing emissions using onboard carbon capture technology (OCCS) falls between the black and red lines on the chart above in EUR per tonne of CO2 (see more ). This technology is in the early stages of being used, with a readiness level of 6 with level 9 indicating that the technology is fully mature and operationally proven in a commercial setting. To move to level 7, it needs to prove how much carbon it can capture effectively (see more ).

Onboard carbon capture might be a better option than switching to other fuels. However, the system for using this technology is still being developed. Right now, the carbon it captures isn't subtracted from the ship's total emissions. A system needs to be created to account for the captured carbon, but it's unclear when this will be ready.

Conclusion

The cost to make the shipping industry more environmentally friendly is quite high. In 2035, using alternative energy carrier will be more expensive than paying the fines for not meeting emissions reduction standards. This and other challenges could threaten plans to lower emissions in shipping. These measures are important for shipping to reach net-zero emissions by 2050, as it currently contributes 2% of the world's greenhouse gas emissions.

Shipping companies face a choice between paying fines or investing in new energy carriers and technologies to significantly cut emissions. In the near future, paying the fines will be cheaper than making these investments. Although there is a pressing need to reduce emissions, the cost of doing so is still too high.