Dutch economy in focus - Resilience of internal demand in the face of external uncertainty

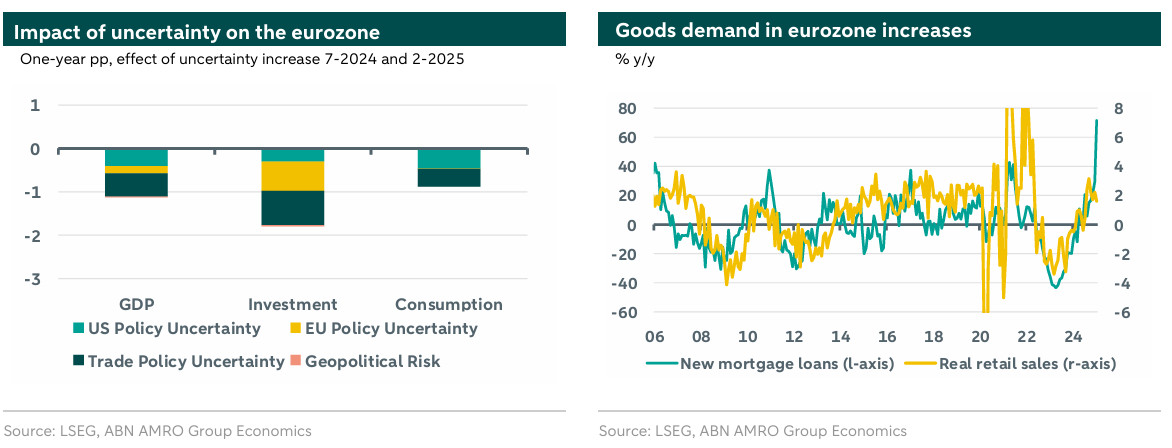

The Dutch economy experienced a notable improvement of growth in 2024; government and household demand were the main drivers. Consumption increases despite household pessimism; higher purchasing power, rising house prices and the tight labour market contribute to consumption growth.

2024 marked a notable improvement

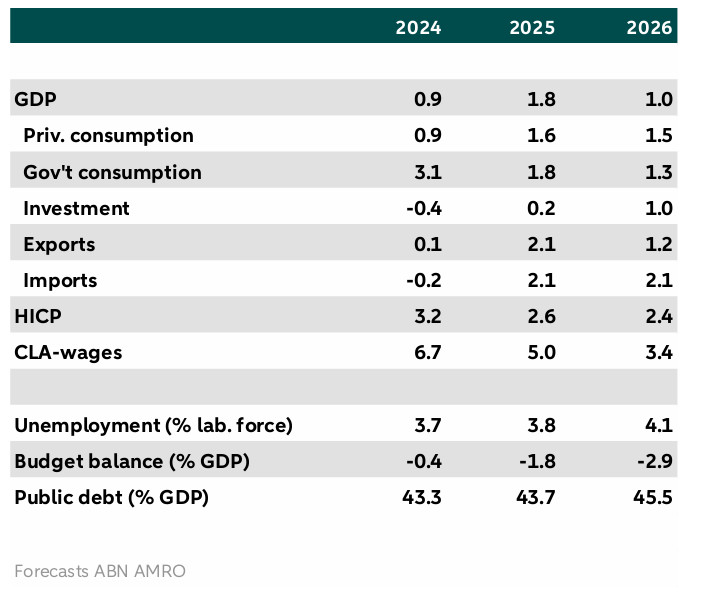

The Dutch economy experienced a robust year, with growth exceptionally high compared to other eurozone countries. After two strong quarters, Dutch GDP grew by 0.4% q/q in the fourth quarter. This brought growth for the whole of 2024 to 0.9%. This is a notable improvement after two years of stagnation.The main drivers of growth in the Dutch economy last year were demand from the government and households. The government's expansionary fiscal policy contributed significantly to growth, with government consumption contributing 0.8pp to annual growth in 2024. In addition, the increase in household real incomes translated into higher consumption in recent quarters.

Looking ahead, we expect growth to be 1.8% y/y in 2025 and 1.0% in 2026. Given the external uncertainty, growth will be domestically driven. In the following paragraphs, we describe the underlying drivers.

From piggy bank to shopping cart

In the first half of 2024, consumers were still keeping a tight hand on their purses, preferring to save and deleverage. Recently, rising real incomes led to higher consumption, thanks to high wage growth that almost completely offsets inflation. Government measures also support purchasing power. Towards the end of 2024, particularly durable consumer goods were purchased more. This was probably due to the changing government policy in 2025 for subsidies on electric cars and heat pumps, which made households want to take quick advantage of the schemes. January's consumption figures show that spending on durables increased less than in December.

Consumption rises despite household pessimism: consumer confidence fell further. This may be related to uncertainty on the (geo)political front. As we describe in another publication, the mere risk of major policy changes can have an impact on the economy even without actual changes. Uncertainty may cause households to save more as a precaution. We therefore think that the savings rate will stabilise at a higher level than before the pandemic. This will put a brake on consumption.

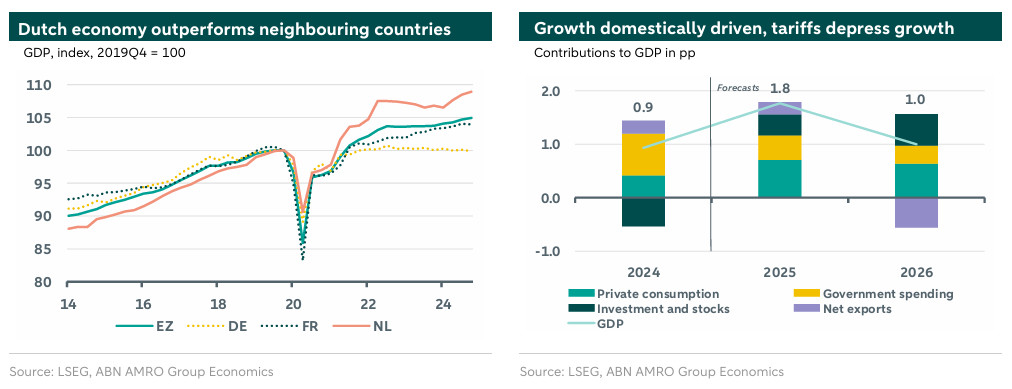

Looking ahead, we expect inflation to fall further gradually but to remain relatively high (read more about our inflation expectations here). Although wage growth is gradually declining, it will remain above inflation in the coming years, meaning that consumers have more to spend. This is also visible in the : purchasing power will rise by an average of 0.6% in 2025 and 1.1% in 2026.

The tight labour market also contributes to consumption growth. Despite rising to its highest level in two years (3.8%), the unemployment rate remains historically low. The labour market is likely to get some breathing space, but given strong labour demand, limited labour supply and an ageing population, unemployment remains low. Consumers do not expect a sharp rise in unemployment either. As a result, the labour market outlook also supports consumption: security for workers and opportunities for entrants.

In addition, consumption is supported by the positive outlook for house prices. The wealth effect, whereby homeowners feel richer due to the increase in the value of their assets, can boost consumption. In addition, the higher number of expected transactions and the increase in new mortgage loans encourages housing market-related purchases, such as furniture.

Despite labour market tightness, the government contributes to growth

The government contributes directly to economic growth, for instance through spending on healthcare, defence, and public administration, as well as public investment. In addition, the government stimulates the economy indirectly by supporting household purchasing power. However, the Dutch labour market remains a bottleneck for the government. Labour shortages prevent some of the spending plans and hampers the implementation of the policy agenda.

On February 26th, the CPB published its economic and fiscal forecasts, kicking off discussions on the Spring Memorandum. The coalition faces significant challenges and choices, such as increasing defence spending, reducing nitrogen emissions, and expanding the electricity grid. The four coalition parties also have several additional wishes. Although the estimated budget deficit for 2025 has been revised downwards and the starting position of public finances is good, the necessary expenditures and desires seem to be greater than the structural budget allows. This could lead to challenging discussions and decisions. Although the coalition has remained intact so far, the upcoming budget discussions may become critical. With the possibility of new elections, there may be a temptation to hand out extra’s.

Rate cuts support investment, but bottlenecks remain

Investment remained robust last year, which is remarkable given higher interest rates, (geo)political uncertainty, the weak German economy, which affects Dutch companies, and the tight labour market, which limits companies' options. Particularly in the last quarter of 2024, investment increased sharply. Investment was especially higher in passenger cars and vans, likely related to changing government policies in 2025: as of 1 January, vehicle tax changes were implemented and regulations around environmental zones in cities were changed.

After this strong fourth quarter, investment will be somewhat weaker in the first quarter. Looking ahead, the delayed pass-through of interest rate cuts by the ECB (read more about our interest rate expectations here) will support investment growth, although it may take longer for the interest rate boost to take effect due to various capacity constraints and bottlenecks. European industry is struggling with relatively high energy prices that are eroding competitiveness. from the persistently tight labour market. Also, companies are not eager to increase their production capacity.

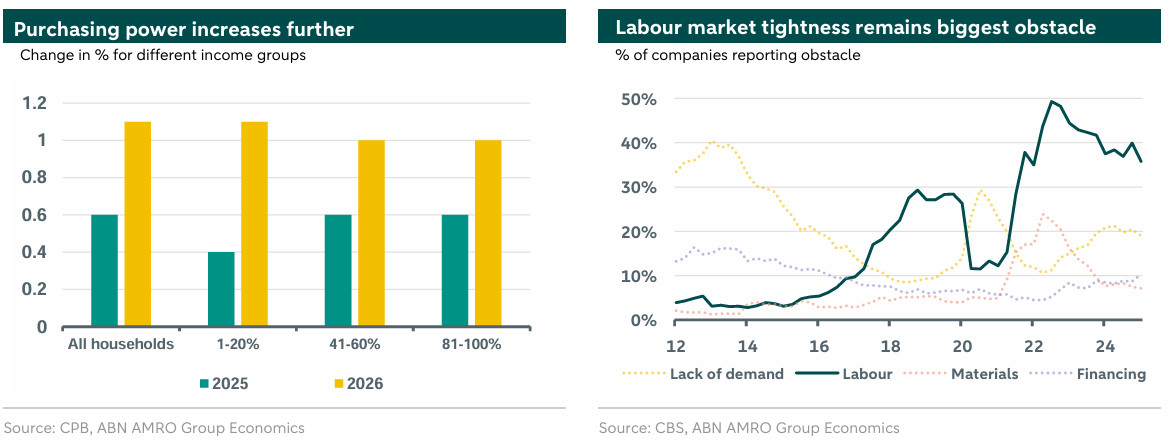

Investment expectations are also affected by uncertainty in the (inter)national sphere, as described in another publication. Uncertainty can lead to delayed or cancelled investment decisions by companies and can make them more cautious about hiring.

Foreign demand picks up

Due to limited demand from the eurozone and weakness in the manufacturing sector, the contribution of net exports has been volatile throughout 2024. In the last quarter, the contribution was strongly positive, mainly due to a sharp fall in imports, likely due to developments in gas markets. Despite limited gas stocks, less gas was imported. With this, destocking contributed strongly negatively in the fourth quarter. This is expected to continue in the first quarter, as inventory drawdown continued.

Looking ahead, we expect foreign demand to pick up. The Dutch industrial sector is showing the first green shoots and global indicators point to a limited improvement in global manufacturing. Dutch exports will also benefit from rising growth in the eurozone, where demand for household goods is picking up.

In contrast, import tariffs will dampen growth. President Trump has threatened a broad package of tariffs. Given that much is still unclear about what will actually be implemented, we make a number of assumptions in our forecasts. As we describe further below, these assumptions are subject to considerable uncertainty. At present, we are working with the assumption that US import tariffs on the rest of the world (excluding China) will come into force in the second half of 2025 and gradually increase to a 5pp rise in the trade-weighted tariff. The recently implemented tariffs on steel and aluminium increase the trade-weighted tariff by about 1.3pp.

It is possible that anticipation of import tariffs will initially lead to a temporary surge in goods exports as US companies stockpile extra supplies. Indeed, there is anecdotal evidence of 'frontloading', but not yet enough to affect macroeconomic figures. But if the import tariffs are actually implemented, foreign demand for Dutch exports will decrease, both directly due to lower demand from the US, and indirectly due to a cooling of the global economy and world trade.

Estimates are accompanied by considerable uncertainty

In recent weeks, international developments have been moving very fast. The main source of uncertainty for our estimates comes from the US, where President Trump is threatening to introduce import tariffs in various ways. Trump is expected to provide more clarity on his tariff plans on 2 April. Given the various developments, we are likely to revise our estimates following this announcement.

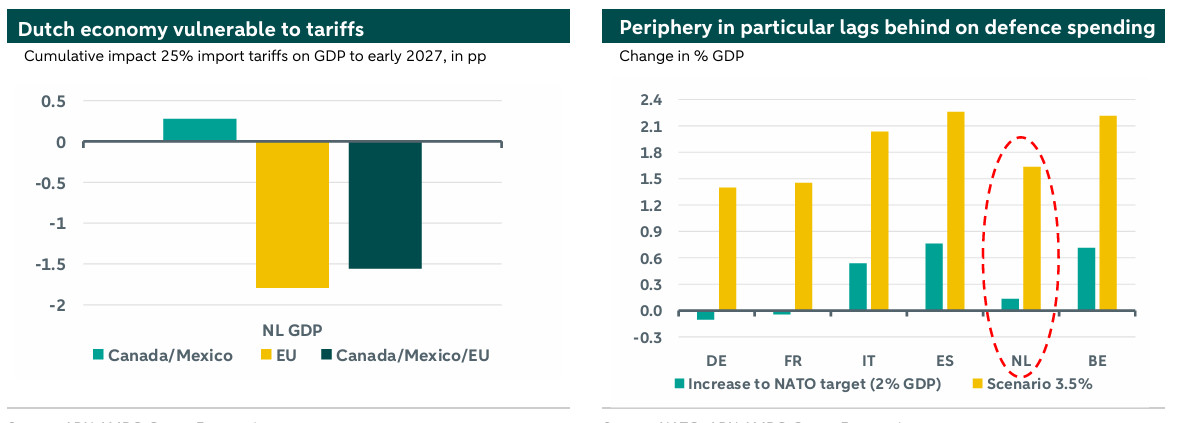

At the time of writing, the 25% import tariffs on steel and aluminium have been implemented. This also affects the Dutch economy. The EU has announced retaliatory measures from 1 April with targeted tariffs similar to Trump's previous administration. The commission is also preparing additional measures scheduled for 13 April. Other tariffs that Trump has threatened with and directly affect the Dutch economy include: 10% global universal tariffs, a 25% universal tariff on EU goods, reciprocal tariffs, and targeted tariffs on cars, semiconductors, pharmaceuticals, wood, copper and alcoholic beverages.

Another factor affecting our forecasts is a possible increase in defence spending. Recent comments by President Trump point to reduced US involvement in NATO, requiring European countries to significantly increase their defence spending. While there seems to be a majority to increase defence spending, no plans have yet been presented on how to do this in the short and long term. The Dutch defence budget for 2025 is €22bn, just below NATO's guideline of 2% of GDP. If this budget increases to 3.5% of GDP, the defence budget will rise to €41bn (read more about the Spring Memorandum negotiations here). This is expected to be gradual, partly due to the tight labour market. Over time, it may contribute positively to growth, but in the short term, the growth impulse is limited given the reliance on importing defence equipment.

In addition, the German government has announced sweeping reforms regarding the German ‘Schuldenbremse’ (debt brake), which will significantly alter the growth outlook. While much depends on the timing and composition of new spending, we assume that growth in the German economy will be boosted by 0.1pp in 2025. A bigger boost is expected for 2026 (0.7pp) and positive momentum is likely to remain in 2027 as well. Given that Germany is the main trading partner for the Dutch economy, this is also expected to contribute positively to the growth of the Dutch economy, as stagnation in Germany has been a drag.