Global Outlook 2025 - The year of the tariff

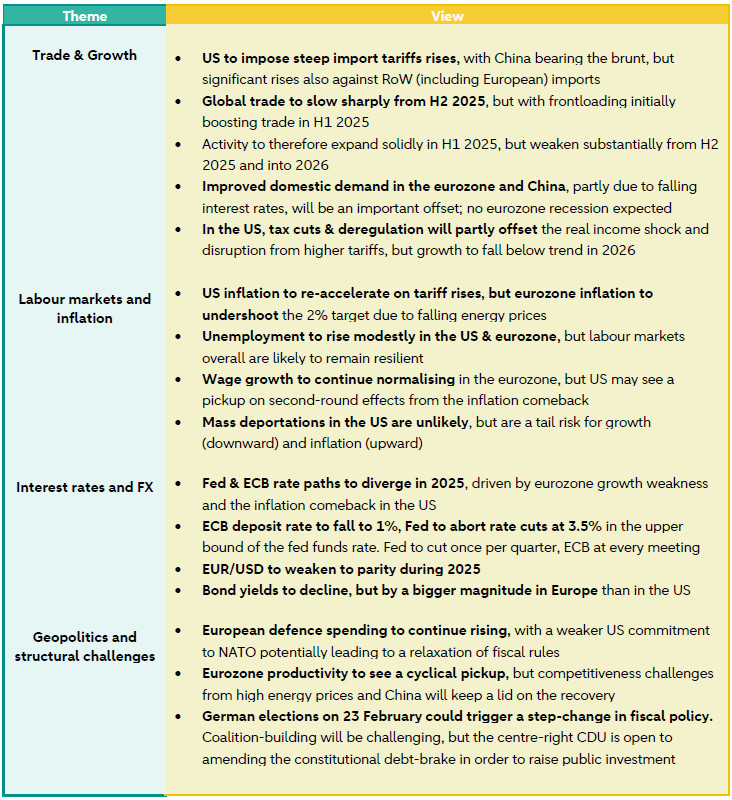

The return of president Trump is likely to mean a significant rise in US import tariffs in 2025. China will bear the brunt, but Europe will also be hit, leading to a sharp slowdown later in the year. Tariffs threaten the nascent recoveries in domestic demand in the eurozone and China, while in the US, deregulation and tax cuts will help blunt the real income shock from tariff rises. Inflation in the US is expected to reaccelerate, but to fall below the 2% target in the eurozone. All of this is likely to drive a divergence in Fed & ECB policy, with slower and fewer Fed rate cuts, and the ECB deposit rate falling to 1%. This will push the euro to parity vs the dollar in the course of 2025.

Global View: 2025 is likely to be a year of major change

In 2025, China will usher in the Year of the Snake. According to eastern lore, the snake is associated with wisdom, charm, elegance, and transformation. The snake has rather different associations in western culture, but transformation – not necessarily of the positive sort – looks set to be an apt description for the coming year. The return of president Trump to the White House is already sending geopolitical shockwaves, well before his inauguration on 20 January. The most notable of these, and one where the effects will be difficult to fully comprehend in the near-term, is his approach to the Russia-Ukraine war. More broadly, and thinking purely of the macro-economic impact, a weakening in the US’ commitment to NATO allies could mean higher European government spending on defence in the coming years, with potentially a relaxation of fiscal rules to enable this. While we can only speculate at this point on the geo-economic ramifications of Trump’s second term, a much more concrete driver of the near-term outlook is likely to be trade tariffs. Trump’s flagship economic policy is massive new tariffs on US imports, particularly against the US’s favourite bug-bear China, but Trump is also threatening much broader tariffs in his coming presidency, including against allies in Europe. In the US, the growth hit from tariffs will – at least initially – be partly offset by the business confidence boost accompanying Trump’s deregulation drive, and a swathe of new tax cuts. For Europe, there will be no such offset, and if tariffs are levied as planned, European exports to the US are likely to be hit hard, with the eurozone’s nascent recovery hitting a brick wall later next year and moving into 2026. Tariffs are also likely to push inflation in the US well above the Fed’s 2% target, while in the eurozone, inflation is more likely to undershoot. This, as we flagged over summer, will drive a renewed transatlantic divergence in interest rate paths – strengthening the dollar and weakening the euro.

Are there any silver linings? The starting point for advanced economies is relatively good. The US has continued to defy expectations of a slowdown, even if this has come at the expense of increased vulnerabilities, such as a persistently low household savings rate and rising delinquency rates on consumer credit. In the eurozone, hard data has come in much stronger than survey indicators suggested, driven by a timely pickup in consumption. In the near-term, activity is likely to see continued support from falling interest rates – which are already feeding through to higher mortgage lending – and solid real income gains. Another silver lining could come from policy changes outside the US. First, China is taking a more activist approach to stimulating demand, and although this is unlikely to boost global growth as much as in the past, it is still likely to give some positive impulse. Second, the German elections in February offer an opportunity for a step-change in the government’s notoriously thrifty budgetary management. Germany certainly is in dire need of greater public and private investment to deal with competitiveness challenges, and it is also one of the few countries with the fiscal space to do so. Whether it chooses to ultimately comes down to politics – and the electorate.

Wherever developments take us in 2025, we wish our readers a restful holiday period, and a happy new year!

New US trade tariffs: 10%? 20%? 2000%?

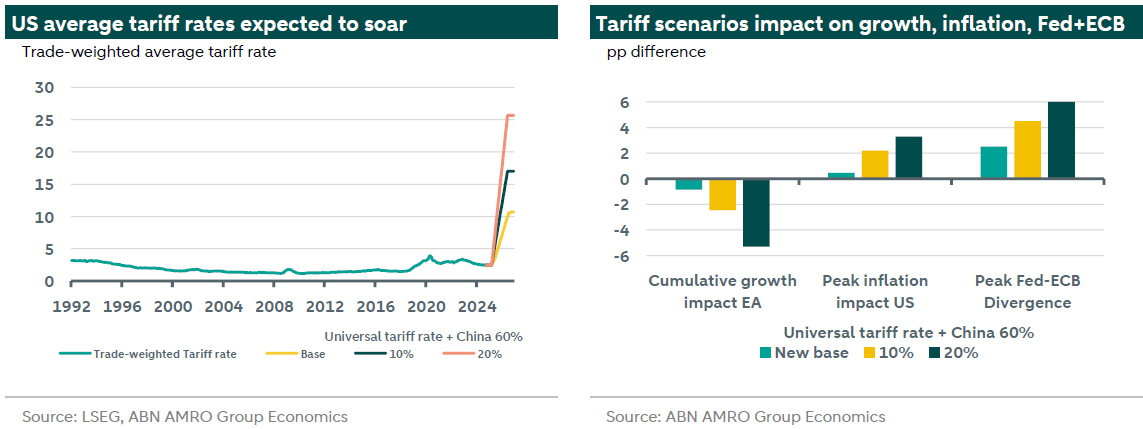

Trump’s proposal for a 10% universal tariff on all US imports, alongside a 60% tariff on imports from China, first surfaced in September 2023 as part of his Republican presidential nomination bid (1). In August 2024, he raised the stakes further by suggesting a 20% baseline tariff. In his most recent remarks – where he said ‘tariff’ is ‘the most beautiful word in the dictionary’ – he even proposed a 2000% tariff specifically on car imports from Mexico.

The wide range of proposals makes it hard to know what to expect. Moreover, might the tariffs be a bargaining chip, to coax the US’s trade partners into dropping their own trade barriers? Leading frontrunners for Trump’s economic team have made comments to that effect, with Treasury Sectretary nominee Scott Bessent calling the strategy ‘escalate to de-escalate’, as a means to get trade partners to for instance drop tariffs against the US car industry. Moreover, it would seem logical for the US to put tariffs on products where it competes, but not on products it does not make itself.

A clear argument against the ‘bargaining chip’ theory is that Trump’s tax cutting plans depend to some extent on revenue from new tariffs. Even with revenues from a full 10% universal tariff, budget deficits would rise from an already high level under current tax cut proposals. While Republicans are not as hawkish over the deficit as they once were, the alternative of completely unfunded tax cuts might be too difficult to stomach, making at least some tariff rises the path of least resistance. Indeed, an added layer of uncertainty to both tariff and the tax cut plans will be the response of Congress. On paper, policy implementation looks easy given the Republican trifecta control of the Presidency, Senate and House. However, the Republican majorities are slim, and it would only take a handful of rebellious Senators or House Republicans to scupper Trump’s plans (whatever they ultimately entail).

In short, the range of possible policy outcomes is huge, with an array of moving parts. We have not even discussed the response of the US’s trade partners to tariff threats yet (see below), which will also surely play a key role in developments. Given the uncertainty, as well as laying out our new base case below, we also show how different tariff scenarios could impact the variables that are likely to be key in driving the ECB-Fed interest rate divergence: growth in the eurozone, and inflation in the US. The bigger the tariffs, the bigger the divergence in interest rates.

Base case: 60% headline China tariff; a 5pp increase in RoW (2) tariffs; limited retaliation

We judge a reasonable base case to involve a sharp rise in tariffs on China imports, and a much smaller – though still significant – rise in tariffs on imports from other countries, including those from Europe. Consistent with the comments from Trump's economics team, we expect considerable variation in tariff rates per product category, such that a standard headline tariff on Chinese imports would be 60% (as proposed), but with many exemptions or much lower rates on goods where there is little direct competition with US manufacturers, as well as higher rates on some others (such as the 100% tariff on Chinese EVs – already in place). Taking this into account, we assume a gradual build-up to an effective average tariff rate of 45% on China imports, up from around 9% currently.

For the rest of the world, we assume a 10% (or even higher) tariff is levied against a number of goods – matching the headline proposal – but that in practice, this will mean a 5pp increase in the average effective tariff rate on all other goods the US imports. There are three reasons for this lower 5pp effective increase. First, the US already levies tariffs on many goods imports, and so raising the tariff to 10% for those products does not have the same effect as raising a tariff rate from 0% to 10%. Second, as for China, we expect many exemptions or lower rates on goods for which the US does not directly compete, or where it is judged that a higher tariff would do more harm than good – or more simply, who has the best lobbyists in the Trump administration. The third reason is that, to some degree, we assume that negotiations between the US and its trade partners succeed in lowering tariffs on US goods (or outright commitments to buy more US goods), causing the US to make further exemptions. As described in our August Monthly, the European Commission has been working on a negotiation plan, with a combination of carrots (commitments to buy more US goods) and sticks (threats to retaliate against politically sensitive goods) to achieve this. For the EU specifically, we do not expect this to fully succeed, but we assume some degree of success, such that the average tariff increase on EU exports rises by 5pp.

In terms of timing, we expect the China tariff rise to be implemented shortly after Trump’s inauguration in Q2 25, and for the RoW tariff rise to happen in Q3 25, following an act of Congress. In both cases, we expect tariff rises to start low and gradually ratchet higher, so as to ease the disruption to the US economy. The China tariffs are clearly the easiest ‘low hanging fruit’ to implement, as the president will most likely use the Section 301 national security provision to bypass Congress for the tariff increase. In any case, the hawkish stance against China has bipartisan support and is the least controversial of Trump’s tariff plans. In contrast, tariffs against the US’s allies and across a much broader swathe of goods will most likely require Congressional approval, making it more difficult and slower to implement.

In the below, we focus our impact analysis on the US and the eurozone aggregate; see our China and Netherlands Outlooks for more specific effects on these countries.

Growth: Tariffs are a clear negative for Europe; offsetting factors blunt the US impact

Ahead of their implementation, tariffs will actually have a positive effect on growth in the eurozone and China, as US importers frontload purchases to avoid higher tariffs. Combined with the recovery in domestic demand, this is likely to lift growth in early 2025. This ‘sugar high’ will prove short-lived, however, with exports likely to see a sharp decline immediately after tariffs are implemented, with trade later settling at its post-tariff ‘new normal’. The US accounts for around 20% of the eurozone’s total exports, and we ultimately expect exports to the US to fall by around 15% relative to the baseline. This lowers GDP growth by around 0.8pp over time. Translating this to quarterly growth, we expect relatively solid growth of 0.4pp q/q in the first half of 2025, with a sharp slowdown to a 0.1-0.2% q/q pace in the second half of 2025 and moving into 2026. While this is well below trend, we do not expect a recession to result from this. With that said, trade-oriented Germany – which remains stuck in an industrial malaise – is particularly vulnerable to new tariffs, and depending on the precise makeup of tariff increases, this could raise the risk of recession given the already weak starting point. As a small open economy, the Netherlands is also particularly vulnerable (see our NL Outlook for more).

The US faces the other side of the tariff coin. Frontloading of imports will actually depress US GDP growth in the course of 2025, recovering once the tariffs are implemented. This means we might see some weakness in headline GDP growth over the course of 2025, while underlying demand remains relatively strong on the back of the economy’s momentum, further lifted by deregulation and significant fiscal stimulus. The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget estimates the Trump budget proposals will add almost 3% of GDP to the deficit. Taking out the cost of the extension of the Trump Tax cuts (TCJA), which is best viewed as the absence of a fiscal contraction, the plans amount to a stimulus of around 1.2% of GDP, although given its distribution, it is likely to have a relatively low fiscal multiplier. At the same time, the price increases from tariffs put a dent in real consumption, and the Fed keeping rates restrictive for longer in response to inflation keeps a mild brake on the economy. The net effect is that the economy loses its momentum and settles into a period of below-trend growth well into 2026.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

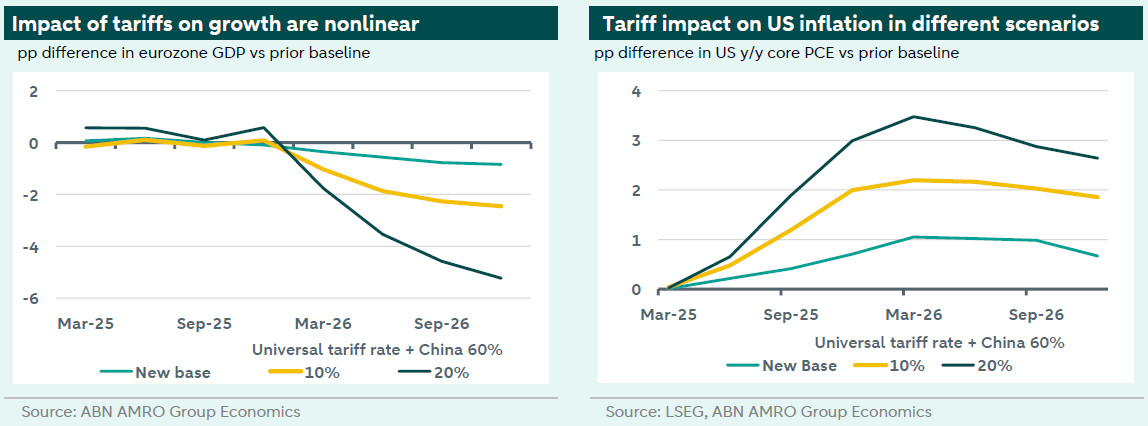

Box: Alternative tariff scenario impact on US & eurozone growth and inflation

There is massive uncertainty over the ultimate extent of new US tariffs, with many moving parts. We have therefore modelled two alternative scenarios to illustrate the effects of: 1) a 10% universal tariff (the original Trump proposal and the likely starting point of negotiations); 2) a 20% universal tariff (his most recent suggestion), with a 60% tariff on China in both scenarios. For eurozone growth, moving up to a 10% universal tariff has fairly linear implications, with the growth hit moving from 0.8pp shock by end 2026 to a c1.7pp shock. In practice, this would mean the eurozone moving from a low growth to a stagnation scenario, with the effect comparable to that of the energy crisis period of 2022-23. The impact takes on non-linear characteristics when moving to the 20% scenario, with a more than 4pp hit to growth, implying deep contractions in economic output. The impact becomes non-linear due to the second round effects on employment and confidence, with the 20% scenario much more likely to lead to widespread layoffs in the sectors most heavily dependent exports to the US. This then sets off a recessionary vicious cycle job layoffs and lower consumption, as the hit to confidence drives more widespread retrenchment among businesses and consumers. This, compounded by lower energy prices due to the hit to global trade, drives inflation even further below the ECB’s 2% target than in our new base case.

For US inflation, moving to the universal tariffs has implications for timing and magnitude. Compared to the staggered approach in our baseline, inflation rises more rapidly. The incremental impact on inflation is almost double that in our base case, and the 20% scenario is again almost double that of the 10% scenario. Here, too, we see a non-linearity but with a decreasing impact on inflation. At first sight this seems like a good thing, but the reason is not. Similar to the eurozone, US growth sees a non-linearly increasing negative impact of the tariffs, as a cycle of lower (real) consumption and job layoffs decreases activity, further amplified by restrictive rates from a central bank that is also facing above target inflation. The significantly weaker economy’s disinflationary pressure ultimately leads to a lower net increase in inflation than a one-to-one pass-through of tariffs to prices would suggest.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

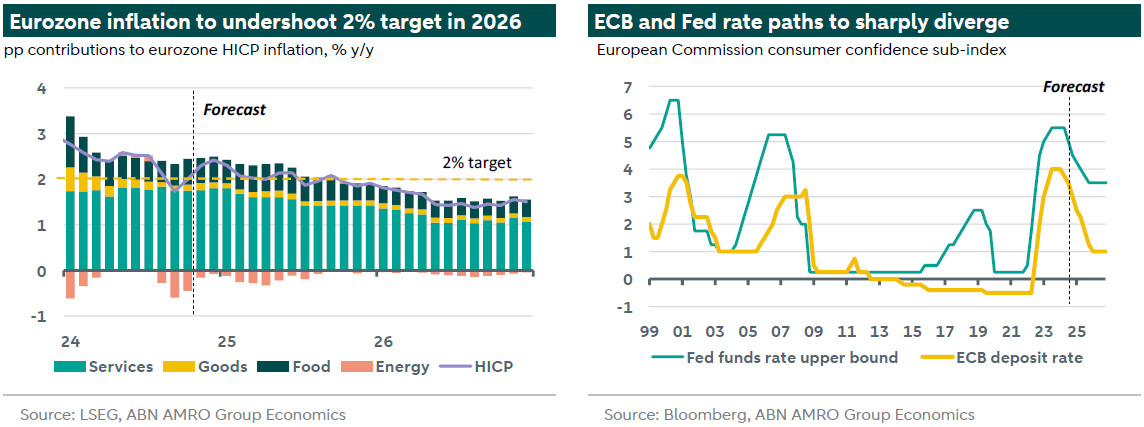

Inflation: US to see renewed overshoot of 2% target, eurozone set to undershoot

The tariffs are likely to have very different effects on inflation in the US and on the rest of the world. In the US, inflation will push the cost of goods higher, and given resilient domestic demand, price rises will likely be directly passed on to consumers. At its peak in Q2 2026, we expect this to raise core PCE inflation some 1.0pp above our prior baseline forecast, pushing core inflation back to well above the Fed’s 2% target to a peak of around 3.3%. This is expected to lead to some second round effects on wage growth in what is still a relatively tight labour market, as workers seek to make up for the shock to their real incomes, and this will then feed again back into higher inflation. The risk – as with any inflation shock but especially now, so soon after the last inflation shock – is that this leads to a de-anchoring of inflation expectations, with inflation settling persistently above the Fed’s 2% target.

In the eurozone, and perhaps counterintuitively, we actually expect tariffs to drive an undershoot of the ECB’s 2% target. This rests partly on the assumption that the EU will retaliate in a limited way to US tariffs, with any retaliatory measures likely to be focused on politically sensitive goods rather than across the board tariffs. However, even with broad tariffs on US imports, the upward impact on inflation would be very small. The US share of eurozone goods imports stands at just 13%; around 20-30% of goods consumption is imported; and goods makes up 26% of the HICP basket. Based on this, a 10% rise in the price of US goods imports would add only 0.1pp to HICP inflation.

Rather, a much bigger effect is expected to be downward, due to the indirect effects of lower energy prices. Tariffs are likely to lead to significantly weaker global trade and global growth, and we have sharply lowered our oil price forecasts as a result. This effect overwhelms any potential upward impact of tariffs via goods. Broadly, we expect HICP inflation to be close to the 2% target in the first half of 2025, before falling substantially below target in the second half of the year, driven by lower oil prices. Additional (albeit much less) downward pressure comes from lower gas and electricity prices due to higher US exports of LNG, with Trump expected to end Biden’s moratorium on new LNG export licenses, while the European Commission is already offering to buy more US LNG as part of its trade negotiations with the US. Finally, though more difficult to estimate, are the effects of lower US demand on both eurozone as well as Chinese goods. This reduced demand impulse will weaken the pricing power of producers, while the impact on labour markets will be to lower the bargaining power of workers (as for instance is now apparent at Volkswagen in Germany).

Interest rates: Slower and fewer Fed cuts; ECB deposit rate to fall back to 1%...

In the near term, we expect both the ECB and Fed to lower rates again at their December policy meetings. Both central banks are on a normalising path, with falling inflation enabling a return to a more neutral policy stance. From a growth perspective, while demand remains solid in the US, there are lingering concerns over the health of the labour market, with for instance job vacancies continuing to decline at a more-than-desirable pace. In the eurozone, while headline GDP growth has come in stronger than suggested by the PMIs, industry remains stuck in a downturn.

While the near-term path for rates is clear for both the ECB and the Fed, from 2025 their paths are likely to diverge – initially by little, and then by a lot. The Fed is expected to slow rate cuts to a quarterly pace, with the first rate cut of 2025 expected in March, and at the end of each quarter thereafter. The ECB in contrast is expected to continue cutting at every meeting – with the exception of a pause in Q2 – when relatively solid growth alongside uncertainty over the outlook for tariffs (and the potential for retaliation) is likely to briefly stay the Governing Council’s hand. Once it becomes clear that eurozone exports to the US will be hit hard by higher tariffs, we then expect the ECB to resume cutting rates at every meeting, until the deposit rate reaches 1% in early 2026. Spurring the ECB to continue cutting will be the growing risk of an undershoot of the 2% inflation target. While this will to a large extent be driven by energy prices, the growth shock from the US tariffs will also pose downside risks to core inflation in the medium term, and this is likely to be the main factor driving continued rate cuts. In contrast, the Fed is expected to continue cutting rates at a slower pace, with the FOMC ultimately forced to abort rate cuts altogether once the upper bound of the fed funds rate reaches 3.5% in late 2025. Around this time, the inflationary pressures of higher tariffs are likely to be pushing inflation increasingly out of reach from the Fed’s 2% target, and the Committee will be concerned about second round effects.

There is enormous uncertainty around this new base case for central banks, with the timing, magnitude, and breadth of any tariff rises a critical determinant of their ultimate impact on growth and inflation. Our view hinges on what Treasury Secretary nominee Bessent refers to as a ‘layering’ – or gradual implementation of – tariff changes. More abrupt changes could mean an earlier end to rate cuts. However, given the ongoing worries over the labour market, and the risks that tariffs pose to the growth outlook further out, we see a high bar to the Fed restarting rate hikes in response to tariffs. The same uncertainty applies to the ECB, but in the opposite direction. Should tariffs be raised more abruptly and by a greater magnitude than we assume, the ECB is likely to cut rates at an even faster pace, with perhaps one or two 50bp cuts, and the deposit rate ultimately falling back to near-zero.

…ultimately driving the euro down to parity with the dollar

Financial markets have already moved significantly to price in Trump’s tariff plans, with rate expectations for the ECB and Fed sharply diverging even before the central banks themselves diverge, and the euro has correspondingly fallen by around 6% against the dollar, from a high in late September of $1.12 to $1.05 at the time of publication. As markets continue to price in the expected divergence in Fed and ECB monetary policy, we expect EUR/USD to weaken further over the coming year, ultimately reaching parity by the end of 2025. As for the ECB-Fed policy divergence, however, the bigger the tariffs, likely the greater potential downside to the euro – at least in the near-term, and up to a point. In a scenario where the tariff rises are so large that they tip the US economy into a recession, the Fed may then have to revert to cutting rates again very sharply. This is particularly likely if the Trump administration succeeds in undermining Fed independence, which is more likely to occur when Chair Powell’s current term ends in 2026.

To some extent, currency moves will blunt both the growth impact on the eurozone, and the inflation impact in the US. However, this will not be sufficient to fully offset the growth shock. While we expect only a 5pp effective rise in the tariff rate on eurozone exports, this is the average, and for some goods we expect the tariff rise to be considerably higher. It is via these more targeted measures that most of the hit to exports – and in turn the growth hit – is expected to materialise. Likewise, for US inflation, a stronger dollar will to some extent dampen the impact, but the overall magnitude of the tariff proposals greatly exceeds the expected appreciation. Against the backdrop of resilient domestic demand, importers weighing the pass-through of (sticky) price increases of tariffs and (more volatile) price decreases via dollar appreciation will likely err on the side of caution and initially take the appreciation as profit margin. Domestic producers will also have stronger pricing power relative to importers, raising the risk of spillover price rises to domestic goods. (Bill Diviney & Rogier Quaedvlieg)

In the below table, we summarise our key judgement calls and assumptions for macro and financial market developments in 2025.

(2) Rest of the World