US Outlook 2024 - Could Trump throw Goldilocks off course?

Strong household balance sheets and improved labour supply have helped stave off a recession. The economy is expected to slow to an average 1% annualised growth over the next three quarters, but a timely pivot to rate cuts by the Fed in June 2024 should keep the slowdown contained. The main risk to the rather Goldilocks-like scenario is a potential Trump victory in the 2024 election. This could herald sweeping new tariffs that put disinflation into reverse, triggering a new hiking cycle.

One could not have hoped for a better performance for the US economy in 2023. Against the backdrop of the biggest interest rate rises in decades – and income-crushing inflation – the economy is now tantalisingly close to a full normalisation from the pandemic shock. Inflation is within touching distance of the Fed’s 2% target, and yet, contrary to going into recession, growth actually accelerated in 2023. How did this happen?

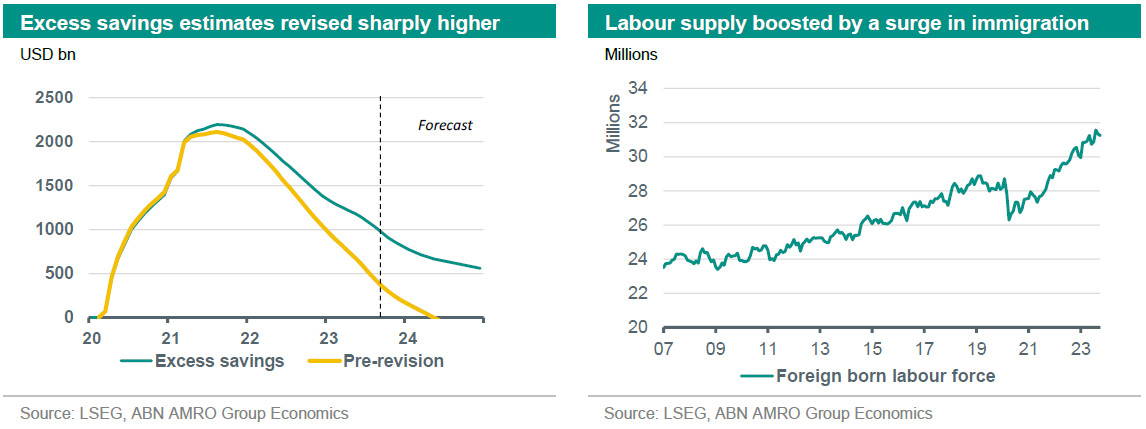

There are two main reasons. The first is that real incomes – and the excess savings buffer thereof – have been significantly higher than we thought they were just a few months ago. This became apparent with the 5-yearly comprehensive update to the national accounts, released on 28 September. It turns out that real incomes suffered less of a hit from high inflation than we thought – to the tune of 7% – while households still have around $1tn in excess savings left from then pandemic, instead of the $0.4tn we thought they would have at this point. This strength in household balance sheets has protected consumers from the jump in interest rates, and as a result, consumption has held up much better than we thought it would.

The second major reason for this strength is an unexpected, significant improvement in labour supply. First, labour force participation is now already back near the pre-pandemic level – we thought that at least some of the post-pandemic fall in participation would be structural (as we see, for instance, in the UK), but that was not the case. The other positive development has been a surge in immigration to the US. Foreign workers initially left the US during the pandemic. They have since come back in droves: there are now around 3 million more foreign workers in the US than there were in 2019, and 5 million more than the pandemic trough in 2020-21.

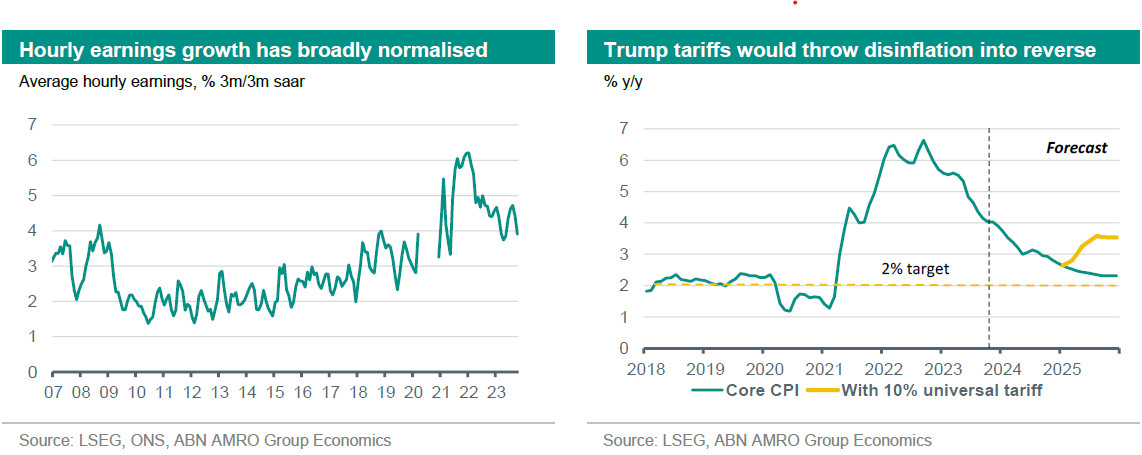

This improvement in labour supply has enabled the economy to continue to grow strongly without inflationary consequences. Indeed, despite labour demand remaining relatively strong, wage growth has fallen across the board, and on some measures is back near the pre-pandemic level. This fall in wage growth has in turn reduced the upward pressure on services inflation, meaning that despite the strength in the economy, inflation has halved from around 6% at the beginning of 2023 to nearer 3% today. As a result, the Fed was able to first slow down its rate rises, and then stop them entirely after the last hike in July. If inflation hadn’t fallen back, the Fed would have likely continued raising rates until ‘something broke’ in the economy. The fall in inflation was therefore critical in the avoidance of recession.

But avoiding recession does not mean the economy won’t weaken going forward, and reduced recession risk does not mean no recession risk. The incoming data for Q4 suggests the economy is slowing sharply: the Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow tracker standing at around 1% q/q annualised, which is in line with our forecast and major pullback from the red-hot 5.2% growth reading for Q3. Our base case sees growth holding at this relatively subdued and well-below-trend rate of 1% over the next three quarters, though the volatility in GDP could even see growth turning negative for a time, with that risk particularly high in Q4. This is because inventory accumulation was a big driver of growth in Q3, and we expect this to go into reverse and be a major drag on growth in Q4. Recent consumption strength also looks unsustainable. While the labour market has been strong in 2023, jobs growth has been on a clear softening path, and combined with slowing real income growth we expect this to dampen spending. There are also signs of increasing stress among some households, with loan delinquencies rising, although the overall strength of household balance sheets is likely to keep this financial stress contained. All told, while high rates means that recession risk still looks somewhat higher than normal – we would put the probability at around 15-20% – this risk looks significantly lower than it did last year, when we had a mild recession as our base case.

Looking beyond the near-term slowdown, we expect the economy to regain momentum in the second half of 2024 and to return to slightly above trend growth in 2025. The main driver of this an expected easing in financial conditions. We expect continued falling inflation – with the Fed’s target of PCE inflation likely to be back near 2% target by mid-2024 – to enable a gradual normalisation of interest rates from June. We expect the upper bound of the fed funds rate to fall to 4.25% by end-2024, and to 3% by mid-2025 – significantly lower than the current 5.50% (albeit somewhat higher than the 2.5% most Fed watchers including ourselves previously thought – see here). Market-based interest rates are already falling in anticipation of the expected rate cuts next year, and so the pass-through to the most interest rate-sensitive parts of the economy – such as housing and goods consumption – should be visible already by late 2024.

Overall, then, it is a relatively benign outlook for the US economy – one could even describe it as ‘goldilocks’-like. What could spoil things? We think the biggest risk to the outlook comes with the potential re-election of former President Trump next November, which according to polls, there is a 50:50 chance of happening. Trump has suggested he would impose a universal 10% minimum tariff on all imports for which the US does not currently levy duties, and further, to impose reciprocal tariff rates in product categories where the US’s trading partners levy higher duties. Trump would face no major hurdle in imposing these tariffs as – similar to the China tariffs of 2017-18 – they are at the discretion of the president and do not require Congressional approval (in contrast, Trump’s plans to roll back Biden’s flagship Inflation Reduction Act would require Republican majorities in both chambers of Congress, and would therefore be much harder to implement).

While a 10% tariff may seem small, its universal nature means that it would have a much bigger impact on inflation than the China tariffs. We estimate the direct effect of this would be to raise US inflation by around 1 percentage point in 2025, if immediately imposed. This may seem relatively small compared to the pandemic and energy crisis shocks. However, the indirect effects could amplify this; for instance, it may push inflation expectations higher and encourage workers to demand higher wages to compensate. And with the Fed having just got through the last traumatic inflation episode, we would expect the Committee to not hesitate in tightening monetary policy in order to pre-empt a move higher in inflation expectations. A renewed tightening cycle in 2025 – when household finances are likely to be in a more fragile state than they are now – could then trigger a recession. Goldilocks better watch out.

This article is part of the Global Outlook 2024