Global Outlook 2024 - Back to not so normal

Advanced economies were resilient last year in the face of the steepest rate rises in decades. While we expect growth to be sluggish for much of 2024, we do not expect a major downturn. Inflation is expected to continue falling, enabling central banks to start the long process of bringing rates back down to normal. We expect the Fed and ECB to cut by 125bp in the second half of 2024. Falling rates should help drive a recovery later in 2024, with momentum picking up in 2025. But risks loom: From a possible Trump 2.0, to a potential EU-China trade spat, and more broadly, the tail-risk of a more disorderly decoupling between the west and China. Whether these risks crystalise or not, the response of central banks will – as always – be crucial in shaping the longer-term impact on the economy. Against this backdrop, climate policy is being increasingly challenged by a political shift to the right.

Looking back, if we were to sum up the economy in 2023 in one word, it would be resilience. Considering the succession of shocks the global economy has faced in recent years – the most recent being the steepest interest rate rises in decades – it is a wonder that the hot topic right now isn't crisis and recession. What about next year? Following the resilience of 2023, we expect 2024 to be a year of normalisation. By the end of next year, we expect inflation to be back at 2%, growth to have returned to trend, and central banks to be well on their way to bringing rates down to more normal levels. So far, so benign. But 2024 also brings a lot of risks. Chief among these is the US presidential election in November, which could herald the return of president Trump. His plan for sweeping new tariffs would put disinflation into reverse, potentially causing rates to start rising again. Another key risk to watch is the outcome of the European Commission's probe into China EV subsidies. Finally, although we do expect policy rates to fall next year (and bond yields have already fallen in anticipation of this), given the monetary policy lags, there is still a risk that there could be more economic weakness in train from high rates than we currently foresee.

Aside from the near-term cyclical worries, in this Global Outlook we also tackle some more structural themes. First, we look at whether higher rates are here to stay, and – related to this – whether persistent price shocks are going to be the new normal (and how willing central banks will be to accommodate them). We also look at a major issue challenging policymakers in recent years – particularly since the pandemic – which is the worsening reliability of statistics, which has meant they (and we) are to some degree ‘flying blind’ in assessing the economy. Finally, we explore what the recent Dutch elections – which led to a surge in support for the far right – might mean for climate policy and the energy transition. To some degree, we think we are likely to see a watering down of climate targets, and this could end up being part of a broader international backlash against climate policy. Next year’s European Parliament elections will be an important test of that.

Wherever developments take us in 2024, we wish our readers a restful holiday period, and a happy new year!

Have we dodged recession? It depends how you define it (and where you look)

Despite the sharpest rise in interest rates in decades, advanced economies have been surprisingly resilient in 2023. Part of the unexpected strength in the US in 2023 has been due to the strong cash buffers of households, where there were large upward revisions to household disposable income and excess savings (see here). Alongside improvements in the supply-side, we expect this to help prevent a more severe slowdown in 2024. Cash buffers have also been a supportive factor in the eurozone, but ECB data shows eurozone households have now spent the bulk of their liquid excess savings in 2022 and 2023H1. Indeed, the household saving rate has increased in recent quarters, suggesting more caution among consumers.

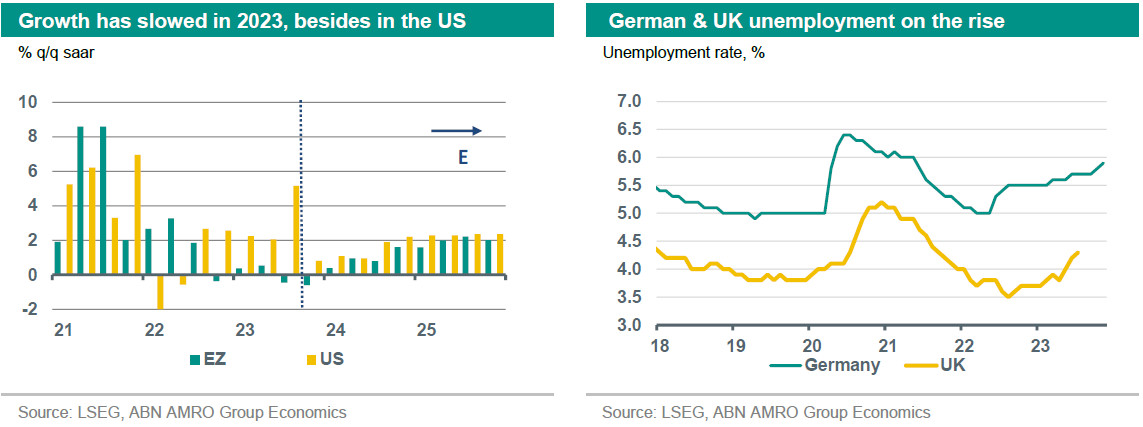

Zooming out, although GDP growth has been stronger than expected, growth still weakened significantly in the course of 2023 (with the exception of the US). Some countries have had occasional declines in GDP (such as Germany, in Q4 22 and in Q3 23), while the Netherlands has recorded three consecutive quarters of contracting GDP, therefore meeting the technical recession definition (see graph below). Others reported zero growth or contraction in 2023Q3, and could well experience another contraction in Q4, as is our base case for the eurozone – i.e. we think the eurozone is already in a technical recession. Still, although we expect a further decline in eurozone GDP in Q4, and see a risk of a one-off decline in the US, we do not expect falls in GDP to last long nor be deep.

But GDP is not the only lens through which we consider whether a country is in recession or not – the labour market is also a crucial indicator(1). Judged through this lens, some countries – notably Germany – do look to be rather recessionary, with unemployment rising nearly a percentage point to 5.9% over the past year, while in the UK, unemployment has risen 0.8pp to 4.3%. This is understandable given that the German and UK economies have essentially stagnated over the past year, and we expect this labour market weakness to spread to other countries over the coming quarters. With that said, although we expect some modest rise in unemployment, on both sides of the Atlantic we expect this rise to be limited to around a 1-1.5pp rise, i.e. we do not expect a sharp rise in unemployment that would normally be associated with recessions.

All in all, our base case sees the global economy remaining sluggish in 2024, staying well below trend for most of the year, but we do not expect a recession. Part of the pain of past ECB and Fed rate rises will still be feeding through with a lag in 2024, and there is a risk even with a June start to interest rate cuts that there is more economic weakness in train than we realise. However, our base case sees the end of rate hikes giving some lift to household and business confidence, which should support consumption and investment. Indeed, financial conditions are already easing ahead of expected rate cuts, with bond yields falling 50-75bp from recent peaks. As an export-dependent economy, we also expect the eurozone to benefit from a bottoming out in global trade and industry (read more in our Macro Watch), as well as easing competitiveness concerns (see section 'Has energy crisis'), though a sharp rebound is unlikely. In contrast, fiscal policy is expected to be tightened, as pandemic and energy crisis-related support is unwound, and this will keep a lid on growth. Taken together, we expect moderate GDP growth in the eurozone and US in 2024, with the growth gap between the two regions narrowing, but the US continuing to outperform somewhat. Momentum should build moving into 2025, when we expect growth to rise somewhat above trend.

When will inflation get back to 2%?

A crucial underpinning for our benign growth view is that inflation continues to move steadily back near the 2% target of central banks – our base case being that this happens by mid-2024. Why is this crucial? Because if this doesn’t happen, central banks could keep rates at restrictive levels for longer than we currently expect. This would then raise the risk of a bigger hit to economic activity than we have seen so far. As we describe below, though, despite growth being stronger than expected, the decline in inflation has actually been broadly in line with our expectations (2). We expect that trend to continue.

Inflation in advanced economies fell sharply in 2023, following the 2021-2 inflationary surge. In the eurozone, most of the decline was due to plummeting energy inflation, which had soared in 2022; but in the US, core inflation (and its main driver, wage growth) has also fallen back significantly. Eurozone energy inflation dropped by more than 30 percentage points (pp) between January and October 2023 (from 18.9% to -11.2%), while food price inflation fell by almost 9pp in the same period. In the US, the comparable drops were 13 and 7pp, respectively. We think the drop in energy inflation has largely run its course, and expect energy prices to increase moderately in 2024, on recovering global demand. Food inflation, in contrast, is expected to fall further in both the US and the eurozone, which will weigh on headline inflation.

More important for the longer run inflation outlook is that core inflation (excluding food and energy) has also declined significantly in 2023, albeit it is somewhat stickier than the headline rate. We think core inflation will continue to fall at a steady pace in 2024. First, non-energy goods price inflation fell sharply in 2023 due to a combination of easing supply chain bottlenecks in global industry and weakening global demand for goods. As global goods demand is expected to recover only moderately in 2024, we expect the downward trend in goods price inflation to continue for a while. Core inflation is also seeing downward pressure from the fall in energy costs to goods and services. This had been a particularly big driver of the inflation surge in the eurozone, and the unwind has further to go, giving extra downward momentum to core inflation in 2024.

Services price inflation has also declined in 2023, albeit more so in the US. Services inflation is more domestically driven than any other component of inflation, and is chiefly driven by wage growth, so the dynamics can vary between countries. In the US, wage growth has largely normalised and is now close to the pre-pandemic level, while in the eurozone it is still somewhat elevated (largely because workers demanded compensation for the real income losses in 2022), although it does now look to be peaking. Indeed, given how much weaker the economy is in the eurozone, we think this elevated wage growth is unsustainable, and expect it to fall sharply in 2024. Another major difference between the US and eurozone relates to shelter (or housing), which has a relatively heavy weight of around a third in the US CPI (rent and owners’ equivalent rent), versus 7% in EZ HICP (only rent). US shelter inflation has declined considerably in 2023, and more timely data on new rental leases suggests it will fall further in 2024. (Aline Schuiling & Bill Diviney)

Links: , , analyses

Have central banks done too much or too little? Are high rates here to stay?

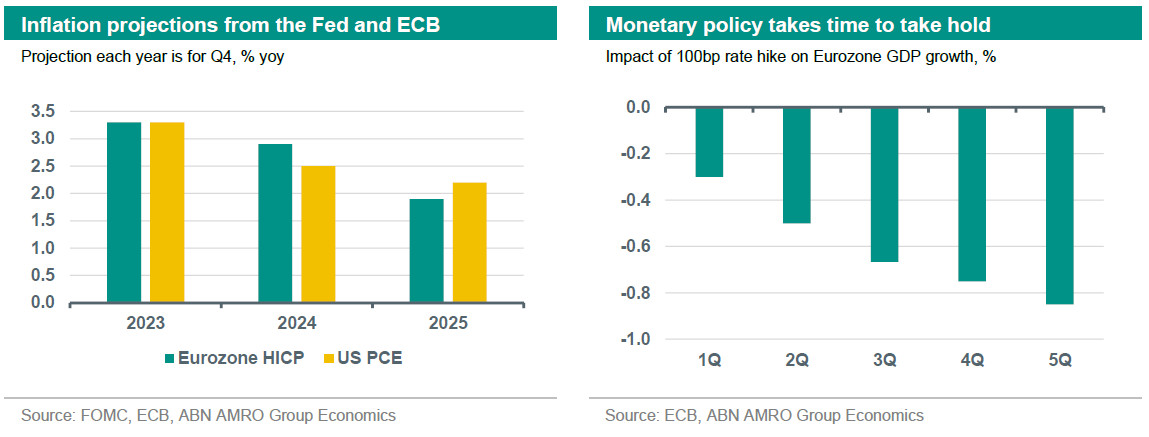

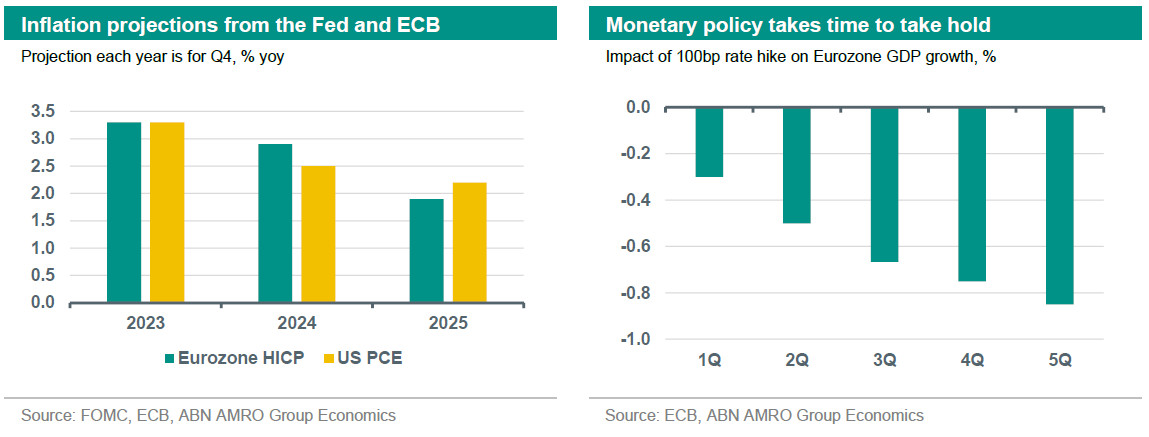

Advanced economy central banks have raised interest rates at the most aggressive pace in decades in response to high inflation. To understand whether they have done too much, or too little to fight inflation, we first need to define what ‘just enough’ would be. The objectives of central banks can give us guidance here. Recent communication from the Fed and the ECB suggests they would be satisfied with inflation sustainably back at around 2% during 2025.(3) According to central banks themselves, they have now done more or less enough to meet their 2% medium-term objective. In the Summary of Economic Projections, FOMC members see inflation just above 2% in Q4 2025. The median projection suggests one more 25bp interest rate increase might be appropriate, though officials are indicating they are comfortable with where interest rates are given that inflation and labour market data since has been generally benign. The ECB’s Staff Macroeconomic projections in September show inflation back around the target in the second half of 2025. The minutes of that meeting – when the ECB raised its policy rate by 25bp to 4% – suggested that decision was a close call. Commentary from Governing Council members also clearly suggests they think rates have peaked if their central view of the economic outlook plays out.

So, central banks appear to judge that they have done just enough. Are they right? Broadly yes, given the current horizon and the upside risks to inflation they were facing over the last few quarters. However, we think the environment is changing, and as we move forward, the horizon is also shifting. Recent data on inflation and its drivers suggest it may come down more quickly than central banks project. In addition, the longer monetary policy is kept restrictive, the more likely we are to see an extended period of weak economic growth, which will eventually lead to undershoots of inflation targets if monetary policy is not recalibrated in time. This is especially true given that the full impact of any rate change takes a long time to feed through to the economy, and even longer to impact inflation. So, ‘just enough’ right now, may easily become ‘too much’ going forward if current interest rate levels are sustained for too long.

Interest rates likely to normalise over the next two years

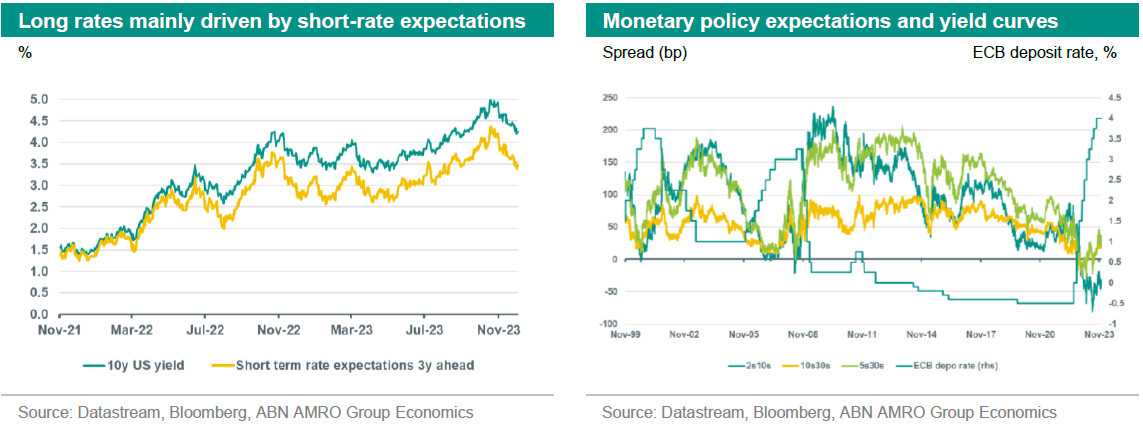

This leads to the question of whether interest rates will remain high. Financial markets appear to have decided they will, though expectations have been scaled back over recent weeks. Just a few weeks ago, financial market pricing suggested investors thought not only that interest rates will be ‘higher for longer’, but rather ‘higher for ever’. For instance, one month ago markets saw US interest rates settling at around 4.5% over the coming years, meaning that even when the Fed starts to cut interest rates, those rate cuts will be rather shallow. This is some 2 percentage points higher than the prior consensus view that 2.5% was normal. Although we have recently seen some re-tracing of these moves, interest rates are still expected to remain much higher than in the past (see chart, below-right). Are financial markets right about the new normal?

We think two factors have driven this change. First, despite the Fed taking the upper bound of its target range to 5.5%, the US economy has been resilient so far. Given that the ‘normal’ or ‘neutral’ interest rate is defined as the level which neither stimulates nor restricts the economy, it seems a logical conclusion to draw that this rate is now higher. However, this conclusion looks premature. Interest rates are not the only factor that impacts the economy. In particular, excess household savings accumulated during the pandemic appear to be insulating the economy to some extent, and this cushion is likely to fade. Furthermore, rate rises impact the economy with long and variable lags, and much of the negative impact is still in the pipeline. For the eurozone economy, which has weakened materially on the back of interest rate hikes, there is obviously much less of a question of whether policy is currently restrictive.

The other factor pointing to a higher normal is 1) a fall in the demand for US Treasury securities, as the Fed reduces its balance sheet, and 2) an increase in their supply, with persist high deficits combined with higher interest costs driving increased bond issuance. We think these are valid reasons to think normal interest rates are higher. Having said this, there are still other factors keeping normal interest rates low. Most importantly, the trend rate of grow remains lower than before the 2008-9 global financial crisis because of unfavourable demographics, and weaker productivity growth.

So, although the normal interest rate may have risen in the US, we think the rise is likely to have been much more moderate than financial markets are currently pricing. In the eurozone, we judge that neutral rates are most likely broadly in line with their pre-pandemic levels. For both the US and eurozone, the most respected estimates of the neutral rate have remained low (see chart below on the left). These estimates appear to be supported by other evidence. For instance, the collapse in corporate loan demand (see chart below on the right) fits the view that monetary policy is in deeply restrictive territory. Overall, we see the neutral rate in the US at around 3%, and the neutral rate in the eurozone at around 1.5%.

The upshot of all this is that as growth and inflation slow, and central banks do start cutting rates, there will still be a long way down from current levels. We therefore expect a downward re-appraisal of the ‘new normal’, which should be a supportive factor next year. Of course, just as rate hikes take time to negatively impact the economy, rate cuts take time to stimulate the economy. As such, compared to cycles where rate cuts came earlier, the recovery could take time to get going.

Bond yields to drop, yield curves to steepen

The most important determinant of long-term interest rates is the market’s view of where the central bank will drive short-term interest rates over the coming years (see chart below-left). Although a risk premium (known as the term premium) also impacts yields, as investors price in inflation risks or changes in the supply and demand for bonds, the chart suggests that monetary policy expectations are the dominant driver. As markets price in more significant rate cuts for next year and beyond, bond yields will likely fall significantly in both the US and the eurozone. We also expect yield curves to steepen. The chart on the right below shows how yield curves move around monetary policy cycles. Yield curves tend to flatten during rate hike cycles, which is exactly what we have seen over the last two years. However, as rate hikes end and rate cuts approach, curves tend to steepen quickly. We have started to see the beginning of this trend, but we think it has much further to go. (Nick Kounis)

What if persistent price shocks are the new normal?

Though our base case sees inflation back near 2% by the middle of 2024 (see section 'Have central banks'), this assumes no further shocks on the scale of the pandemic or the Russia-Ukraine war. Such ‘shocks’, of course, are by definition impossible to predict. In the decade prior to the pandemic, inflation was persistently below central bank targets. Trade integration pushed down prices of goods, while lacklustre growth and slack in labour markets led to weak demand-side prices pressure. Now, after the energy crisis set off the biggest price shock since the 1970s, there are reasons to think the coming decade could bring more price turbulence. Two factors stand tall as potential new sources of price shocks: 1) geopolitics and deglobalisation, and 2) climate change and decarbonisation. But as Milton Friedman once said, “inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon.” Shocks can temporarily disturb the inflation anchor, but whether high inflation really persists will depend on the central bank response.

‘Shifts’ are not ‘shocks’ – and the distinction matters

The global turbulence of recent years makes it easier to imagine new sources of shocks. One concrete risk to inflation on the horizon comes with the possible re-election of Donald Trump to the US presidency, which could bring broadbased new import tariffs – this is something we discuss in more detail in our US outlook. But for a shock to really be a shock, it needs to be big, and it needs to be unanticipated. To illustrate with a recent example: if Europe had expected Russia would invade Ukraine and weaponise its gas exports, energy supply would have been diversified more gradually, and the impact on energy prices would have been much milder.(4) Indeed, demographic change is an example of a more gradual shift rather than a shock, with its effect more gradually absorbed by the economy.

That 1970s feeling: The impact on expectations – and the policy response – is key

Inflationary turbulence is nothing new, but the scale of the supply shocks we have seen from the pandemic and the Russia-Ukraine war has dwarfed anything seen since the 1970s oil price shocks. This is why the recent inflation surge initially blindsided central banks (although ). Economics 101 teaches that a central bank should ‘look through’ (or wait out) rather than clobber the economy unnecessarily with high interest rates. Supply shocks typically only temporarily raise inflation until supply adjusts, while monetary policy can only influence demand (and with a long lag) – not supply. But when it became clear in 2021-22 that the unfolding shocks were sufficiently large and persistent to risk a de-anchoring of inflation expectations, central banks acted with the most aggressive rate hike campaign in decades. What worried central banks was the second round effects – that higher prices would push people in a tight labour market to demand higher wages, risking a wage-price spiral. To some extent, this risk did indeed crystalise. In responding so forcefully, they knew full well that this risked triggering deep recessions. But their judgment was (and remains) that killing inflation now – even if it meant recession – was better than a re-run of the 1970s, when persistent inflation led to a highly volatile business cycle, and prolonged high unemployment.

Central banks appear committed to their targets, but will that always be so?

Central bankers surprised markets and forecasters in how aggressively they responded to the 2021-22 inflationary surge. This sent the clear message that, when push comes to shove, meeting their inflation targets matters more than avoiding a near-term recession.(5) We are confident that will continue to be the case, but we can also imagine scenarios where things could go differently. First, it could be that shocks are so numerous, and so varied in their nature, that the recession and unemployment consequences of bringing inflation back to target becomes intolerable. Related to that is the issue of hard-won central bank independence, which is a relatively recent phenomenon for most countries/regions (in the past, politicians had direct influence over interest rates). We could therefore also imagine scenarios where political pressure impedes a central bank from meeting its mandate; particularly in the current environment, where populist politicians with less respect for institutional boundaries increasingly hold sway (6). (Jan-Paul van de Kerke & Bill Diviney)

Will elections intensify China’s decoupling from the west?

The west’s decoupling from China seems to have become the new normal. Relations are undergoing a reset – driven by both sides – over concerns on strategic competition, national security and other issues. The reset goes hand in hand with a correction in bilateral trade, although cyclical factors and a post-pandemic rotation in demand back to services from goods also play a role. Alongside trade, this is affecting foreign direct investment and portfolio flows, particularly in the tech sector (see our October Monthly, Six urgent questions on China and our recent trade watch). Our base case sees China decoupling continuing in a gradual way (given vested interests at stake), with no Russian-style accidents leading to sudden stops with severe macro implications. Still, we see three potential stumbling blocks in 2024 that could accelerate China decoupling: Taiwan elections (January), US elections (November), and an EU-China trade spat on EVs.

Taiwan presidential elections: Risks from DPP victory remain, but are mitigated by restart US-China (military) talks

Taiwan is a key friction point in US-China relations, with China aiming for reunification over time (preferably peacefully, but if necessary by force) and the US being the island’s major backer. The fact that Taiwan is the world’s largest semiconductor producer adds further to these frictions. Events last year showed how precarious the status quo is, as China reacted with large-scale military exercises and a de facto blockade of the Taiwan Strait to the Taipei visit of US House Speaker Pelosi in August 2022. Against this background, Taiwanese presidential elections (January 13) bear close watching. A victory for the pro-independence Democratic Progressive Party’s candidate Lai (who is criticised by China) would add to risks of a reaction by Beijing, although Lai has softened his tone recently (the majority of the voters prefer stable cross-Strait relations). Lai is leading in the polls and his chances of winning the elections improved after a plan for the opposition pro-China Kuomintang party (favoured by Beijing) and the centrist Taiwan People’s Party to join forces failed end-November. On the other hand, Biden and Xi discussed Taiwan during their recent meeting, and agreed to reopen military communication channels that had been closed after Pelosi’s visit. This has somewhat lowered the risk of an escalation in the Taiwan Strait following the January elections, at least for the short term, though some risk naturally remains.

US elections November 2023: What if Trump returns to the White House ‘with a vengeance’?

Beyond 2024, the US presidential elections next November will also have repercussions for the US-China relationship. Polls suggest that former president Trump is all-but certain to win the Republican candidacy, with a 50-50 chance of him going on to win the presidency, despite his legal woes. While rebuilding US industrial policy and containing China are now bipartisan goals, the approaches of Trump and Biden are radically different. Whereas Trump’s approach was mercantilist, transaction-based and unilateral, Biden’s approach is more ideologically-based and multilateral. A re-elected Trump would likely play the protectionist card again: he has proposed a universal 10% import tariff (using presidential powers under Section 301 of the 1974 US Trade Act), which would hit the EU as well. He may also come with another round of China tariffs, as the US still has a large bilateral trade deficit (although this has come down, with US demand rotating back to services). All in all, we think a Republican/Trump re-election would raise the risk of a more abrupt deterioration in US-China relations, with a stronger macro/markets impact, and an acceleration in US-China decoupling. Another round of US isolationism under Trump 2.0 may also embolden China in its longer-term approach versus Taiwan.

Will the EU probe into China’s EV sector trigger a serious trade spat between Brussels and Beijing?

The EU has so far taken a more measured approach in reshaping its China relationship compared to the US. More recently, however, the EU trade-offs seem to have shifted. In September 2023, the European Commission (EC) launched an investigation into made-in-China battery electric vehicle (BEV) subsidies, following a surge in China’s BEV exports, which could harm Europe’s nascent BEV industry. While BEVs still make up a relatively small share of total EU car sales, at 12.2% in 2022, sales are growing rapidly – by over 50% ytd y/y as of October. In Q2 2023, 18.5% of EU imports of BEVs were from China and, although this share has dropped somewhat recently, is expected to increase over time. Around 40% of the EU imports of China-made cars came from Tesla, but the share of Chinese brands is rising rapidly.

To be able to impose countervailing duties (such as a higher import tariff, on top of the standard 10%), the EC must prove a) that Chinese BEV exports received equivalent subsidies from the Chinese government, and b) that European industry is imminently threatened by this. The EC probe will look at a range of support measures by the Chinese government (such as subsidies, grants, loans), will last for about one year, and will cover the period October 2022-September 2023.Although some countervailing measures may well be taken given the importance of the BEV industry for Europe, we expect Brussels to act carefully in this area, as it usually does given the broader interdependencies at stake, and with the possibility of Chinese retaliation in mind. That said, there is a risk of a more disruptive outcome, which could accelerate Europe’s decoupling from China. (Arjen van Dijkhuizen & Aggie van Huisseling)

Has the energy crisis and the subsequent jump in wages hampered Europe’s competitiveness?

High nominal wage growth and a shift away from Russian energy towards more costly suppliers has dented the eurozone’s cost competitiveness. Business surveys, for instance by the European Commission indicate that eurozone businesses perceive a loss of competitiveness in domestic as well as international markets. This has knock-on effects: higher energy costs mean the eurozone lost some of its attractiveness as an area to invest in. There are offsetting factors though, which makes us believe loss of competitiveness is bottoming out. For a brief time, weakness in the euro dampened some of these effects. Also, lower inflation and increasing unemployment will reduce wage pressure in the coming quarters, which will weigh on unit labour cost growth. In the longer term, cost competitiveness hinges on innovation and productivity developments, where there is room for policymakers to act to improve future cost competitiveness.

Cost-push shocks hampering competitiveness

Since the war in Ukraine and the subsequent energy crisis, energy costs soared more for eurozone firms than for most global competitors (7). As the eurozone remains a net importer of energy, this is unlikely to fully reverse soon. This constitutes a disadvantage for eurozone industry, particularly the more energy-intensive (including in the Netherlands, see our report here). According to investment surveys, high energy costs are also holding back new investment. Next to energy, high inflation against the backdrop of a tight labour market has led to high nominal wage increases. Without increases in productivity, this has meant rising unit labour costs (the cost of labour per unit of output). Looking at unit labour cost developments, the recent increases have far exceeded the increases seen in the three years leading up to the pandemic.

As a result of these shocks, eurozone businesses report that their competitive position is slipping. This is more the case for exporters than for those producing for the domestic market. Interestingly, we also see signs of divergence within the eurozone. Particularly in terms of the competitive position in relation to energy. German businesses for instance, heavily dependent upon Russian gas for their energy-intensive industry, report a far steeper loss of competitiveness than for instance their French or Italian counterparts.

Several factors provide temporary cushioning

There have been some off-setting factors that have reduced the perceived loss of competitiveness. First is exchange rate developments. When energy costs soared in 2022, the euro depreciated in value. This provided some relief for exporters, though it is a double-edged sword for energy-intensive exporters, as a weaker currency also puts upward pressure on input prices. Another temporary cushion over the past two years came from supply bottlenecks elsewhere in competitor countries. In 2021 and 2022 following the lockdowns, global supply chains were distorted leading to inefficiencies in logistics and international trade. As a result, domestic producers within the eurozone, even when they were more costly, gained an edge over international competitors as they were less affected by these global supply bottlenecks. This shielded domestic producers temporarily from the full extent of their loss of competitiveness. More recently, these two factors retreated; supply bottlenecks have since resolved and the euro has appreciated from the 2022 lows.

Going forward a bottoming out in competitiveness losses is expected

It remains to be seen whether the current dent in euro area competitiveness becomes structural, for now we expect a bottoming out in this loss of competitiveness. For instance, because labour costs pressures are expected to decrease. amid economic weakness (see here) and declining labour demand, labour markets are set to cool further and unemployment will pick up, which will further alleviate wage pressure. Not only will lower wage growth put a lid on rising unit labour costs, but so will rising layoffs, as business restructure in response to weak demand.

Europe’s dependence on imported energy is unlikely to stop anytime soon, but measures are being taken to reduce it. In the past year a lot of progress has already been made in this area: supply of renewable energy has been ramped up, and energy demand from euro area businesses has fallen significantly, output kept stable constant. Indeed, one upside is that Europe arguably took a considerable step forward compared to most of the world when it comes to energy efficiency, which is essential in the energy transition. For specific energy intensive sectors, governments have implemented state aid schemes to assist those sectors and companies affected mostly. Still, despite these efforts the loss of competitiveness is visible. The coming years will show whether more progress will be made in this area and whether differences in energy input prices will decline as a result of current and future policies.

In the long term it is all about productivity growth

Longer term competitiveness is primarily driven by productivity growth. The recent track record in this area is not promising. Productivity growth has been low in most advanced economies, but the eurozone seems to lag behind other major regions. The productivity puzzle is not an easy one to crack. Indeed, national governments as well as the European Commission have tried a range of approaches to raise productivity, from capital market deepening, to improving the functioning of the internal market, to setting up public investment funds, such as the recovery and resilience fund. While this policy agenda is important from a structural angle, it is unlikely to provide any near-term relief to businesses facing a loss of competitiveness currently. (Philip Bokeloh & Jan-Paul van de Kerke)

What the Dutch election outcome could mean for the way forward on climate

General elections can trigger a shift in climate policies, according to the . We add that litigation can also trigger such a shift. In this note we argue why we think a shift away from an orderly transition towards a more delayed transition is now a more likely scenario for the Netherlands.

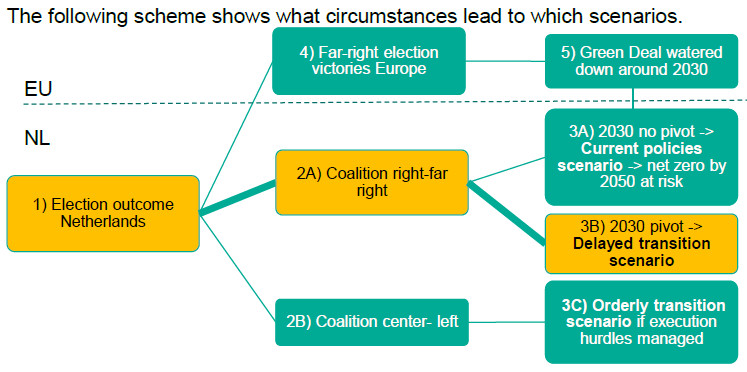

Indeed, the likely climate scenario of the Netherlands between now and 2050 is affected both directly and indirectly by the outcome of Dutch parliamentary election last month, which saw a climate sceptic party (PVV) winning the largest number of seats. The scheme below outlines the possible outcomes following this victory (1).

First, there is the direct impact of a new coalition. With a centre-left coalition (2B), ambitious energy transition policies are likely to stay on course (3C). These are to enable 55 percent emissions reduction in an orderly fashion (8) by 2030. Alternatively, a far-right coalition may decide to slow or even reverse emissions reduction (2A), by rowing back on these policies. As the election was won by a party (PVV) that argues climate mitigation in the Netherlands is a useless activity, a slow down or reversal of the emission pathway is deemed more likely.

Should a new government decide to row back on climate policies, the next question is whether a subsequent government then lurches towards more disorderly transition policies again around 2030 so that net zero targets are achievable by 2050.

Here we see two scenarios: one is where the legal and policy context of the Netherlands around 2030 enforces a decisive pivot that puts the Netherlands on a delayed transition path to still achieve net zero by 2050 (3B). Alternatively, the less ambitious climate agenda could continue after 2030, which puts emissions on a path where net zero by 2050 is out of reach (3A). For a medium-term pivot (around 2030) to be realistic, the direction the EU takes on climate policy matters. The 2024 European Parliament (EP) elections are therefore a key event to watch (4). If a more right-wing Parliament significantly waters down the Green Deal (5), it could reduce the legal necessity for a policy pivot further down the line in the Netherlands, making it highly unlikely the 2050 goals will be reached (3A).

We think a shift away from an orderly transition towards a more delayed transition is now a more likely scenario for the Netherlands (yellow). A climate sceptic coalition in the Netherlands, together with a still ambitious Green Deal from Europe and litigation cases that try to enforce climate policy execution to be in line with legal commitments, is likely to put the Netherlands more towards the delayed transition path, which is more costly than an orderly transition path in terms of its macro-economic consequences.

The Dutch elections: a (far) right-wing coalition most likely

Elections for the Dutch parliament were held on 22 November. The PVV – a far-right party with leader Geert Wilders – surprised by winning 37 out of the 150 seats. 76 seats are required for a majority in the parliament, so Wilders is now looking to the centre-right VVD and NSC parties (81 seats) to form a right-wing coalition with VVD and NSC. If you add BBB to this picture – which is attractive due to its position in the Senate – the coalition would have 88 seats. Since NSC and VVD expressed some concerns regarding aspects of the PVV party programme, a complicated negotiation process is now expected to follow. Indeed, the VVD recently stated it will not join a coalition, but rather support it from outside.

Big policy shifts expected in the area of climate and Europe

The PVV will likely be in favour of cutting spending on climate and energy-transition related projects. According to the party, the current Climate Law – which commits the Netherlands to reduce carbon emissions by 55% in 2030 and become climate neutral in 2050 – should be scrapped. The PVV is most vocal about cutting renewable energy investment. The other potential coalition parties are generally less ambitious on decarbonisation. With NSC and VVD in favour of nuclear energy, it is possible we see a shift away from renewables to nuclear. Similar to the PVV, the NSC believes no mandatory switch to heat-pumps should be made, and they are calling for long-term LNG deals and further exploration of gas in the North-Sea.

Next to climate, Europe is an area where all parties of the possible coalition favour a less accommodative policy. While PVV’s idea of a Nexit (Netherlands Exit) is not supported by the other parties, the generally eurosceptic sentiment of the PVV is likely to be supported by the VVD and NSC. The new coalition is therefore likely to be more antagonistic towards the EU than the most recent government, particularly if EU policy comes into conflict with a domestic desire to water down climate policy.

The Dutch elections as canary in the coal mine?

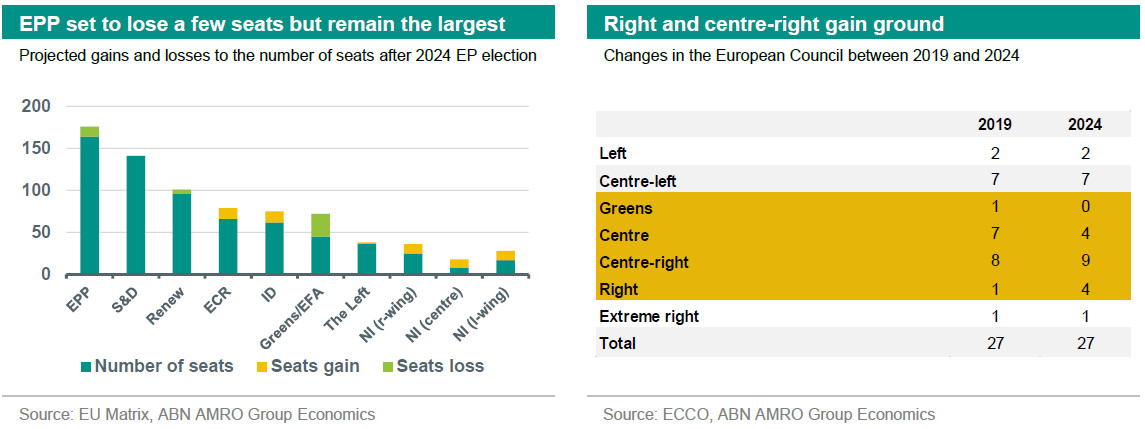

The Dutch elections could prove a canary in the coal mine for the EP elections coming up in May 2024, signalling a bigger chance of broader shifts to the right in Europe. Based on national elections, the green and centrist parties are likely to lose ground, while centre-right and right gain ground (see chart below). Polls for the EP elections suggest a slight shift towards the right. However, even if the EP does move to the right, the centrist parties (mainly the EPP which is a strong advocate of the Green Deal) have such a large majority that their dominance is unlikely to be fully lost in one election round. This means that at this point, it seems the Green Deal is likely to remain intact. However, with Dutch climate policy diverging more from European targets, there is a chance that national execution is watered down.

Green Deal safe but risks to implementation

Although the Green Deal is safe according to current polls, there is a risk that climate policy gets watered down on a national level and that there is weaker implementation of the Green Deal at the European level.

Climate policies are facing a growing backlash beyond the Netherlands. For example, Germany has watered down plans that encourage switching from gas boilers to heat pumps. In the UK, the ban on internal combustion engine cars was delayed. Recent polls suggest voters increasingly favour parties that put industry over climate. This increases the chances of climate policy being watered down in more countries.

The departure of Frans Timmermans – who was a vocal Commission vice-president for the Green Deal and climate action – might raise the chances of weaker implementation of the Green Deal with the current Commission. In the longer term, there will be another round of EP elections before 2030. This could increase the chance of a bigger right-wing parliament, which would be a risk for the Green Deal and climate policy.

Policy divergence or litigation will likely bring Dutch climate policy to a pivot by 2030

With a possible coalition which may be less ambitious on climate, and a Green Deal that remains intact, this means that Dutch policy could gradually diverge from European goals. This divergence could mean a sharp lurch back to energy transition policies after 2030 if new elections are won by parties supportive of that.

On top of elections, litigation could also cause a sharp policy turnaround to comply with legal commitments. Climate litigation cases (9) more than doubled globally in the last five years. The majority of the 62 cases in the EU (as of end 2022) were cases against the government. In France, the UK and in Germany, cases which call for governments to comply with and implement their own legally binding mitigation commitments to the Net Zero target. The Urgenda in the Netherlands is the most famous example of litigation triggering a sharp policy turnaround.

Delayed transition scenario becomes more likely

In economic terms, this means that the transition pathway moves more towards a ‘delayed transition’ scenario and moves away from an ‘orderly Net Zero’ scenario. This, in turn, implies more medium-term economic damage. A delayed transition scenario would require a sharp pivot after 2030, for which stronger policy measures would be needed. This creates more transition risk than in the orderly scenario, as it implies firms and households have less time to prepare for emissions reduction, hampering investment and consumption in particular. Additionally, rising carbon prices would push inflation higher. Through these channels, we would see weaker GDP growth than in an orderly scenario (see chart below).

Climate scenarios, such as those of the , thus illustrate that an immediate coordinated transition is less costly than a disorderly delayed transition in terms of medium-term GDP impact. In other words, an orderly transition is better for a longer-term economic growth. (Sandra Phlippen, Aggie van Huisseling, Anke Martens)

(1) Indeed, in the US, the official arbiter of recessions – the NBER – as “a significant decline in economic activity that is spread across the economy and lasts more than a few months.” This broader definition typically also requires a rise in unemployment.(2) Interestingly, this suggests a reversion to the pre-pandemic experience, when the relation between growth, the labour market and inflation became much weaker than it was in the past. (3) Although the FOMC also has a ‘full employment’ objective, Chair Powell has clarified that price stability is seen by the Committee as a necessary pre-condition to achieving full employment over the long term. (4) The energy crisis has also made economies more resilient to a new energy shock: energy supply is more diversified, while policymakers and consumers are better prepared to adapt. Consecutive similar supply shocks can be thought to have less impact on inflation.(5) This also applies to the Fed, which unlike the ECB, has a dual mandate: price stability and full employment. However, as Chair Powell always argues, price stability is a pre-requisite for a strong labour market, meaning that the Fed’s de facto goal is also singularly on inflation.(6) A recent example of this is Turkey. Under pressure from the government, the central bank cut rates in response to surging inflation.(7) Japan and Korea – also major net importers of LNG – were also hit by the energy crisis and continue to face higher energy costs than before the crisis. (8) Assuming execution hurdles are overcome. (9) Climate change litigation includes cases that raise material issues of law or fact relating to climate change mitigation, adaptation or the science of climate change (Sabin Center for Climate Change Law 2022a). Such cases are brought before a range of administrative, judicial and other adjudicatory bodies.