US Watch - FOMC Preview – Hare Market and Tortoise Fed

The Fed is likely to start its easing cycle with a 25 bps cut on September 18th. The labor market is softening, but it does not warrant an aggressive easing cycle. We expect a steady easing path with the Fed having the luxury to remain data dependent. The risk of an unforeseen labor market deterioration exceeds the risk of sticky inflation, election-induced economic uncertainty plays a role.

Next week Wednesday, on September 18th, the Federal Reserve will start its easing cycle. Chair Powell effectively confirmed the start of the easing cycle in his Jackson Hole speech, but expectations on the magnitude of the initial step, and the overall steepness of the path have varied widely. On August 1st, markets priced 28 bps for September. Since then, the September pricing peaked at 61 bps following the July labor market report, before easing down to around 29 bps as of today. As for steepness, markets priced 72 bps until December at the beginning of August, and are currently pricing about 104 bps.

In this piece we discuss our view on the likely easing path. The first question is whether the initial cut will be 25 or 50 bps, which is really asking: has the economy already deteriorated so strongly that the Fed is behind the curve in easing? The second question is how aggressive will the remainder of the easing path be? This is a question on how likely the economy is to deteriorate further, and potentially more rapidly, over the next year.

Will the Fed start with 25 or 50 bps?

With inflation receding, and a softening of labor market data, the risks to the Fed’s dual mandate are coming into balance, heralding the start of the easing cycle in the next FOMC meeting. Several officials have confirmed that they believe it’s time to start cutting rates in September, but all have been silent about the size of the initial step. In the July meeting’s press conference, Powell laughed at the thought of a 50 bps cut, but two days later, markets were pricing in an intermeeting 50 bps cut following the disappointing July labour data release. Since then, markets have calmed, but there is still a fierce debate on whether the initial cut will be 25 or 50 bps. The former is seen as the default option, with proponents of a 50 bps cut typically citing one of two arguments. The first is that a recession is coming soon or has already started, to which an aggressive easing cycle would be the appropriate response. The second argument is that the neutral rate is appropriate policy for the current juncture, and the proposal is to get the policy rate there as quickly as possible. There is often also a ‘passive tightening’ argument involved that states that, through steady disinflation, policy is currently the most restrictive it has been in real terms. Arguments against a 50 bps cut are generally hawkish in nature, i.e. inflation is not yet at target, or behavioural, in that markets might interpret a 50 bps easing as a Fed-sponsored indicator of an impeding recession. Above all, a 25 bps cut would be appropriate in the absence of a convincing reason for 50 bps, as slow and steady easing minimizes the chance of policy-induced frictions, the likes of which we saw during the aggressive hiking path in the form of a mini banking crisis in early 2023.

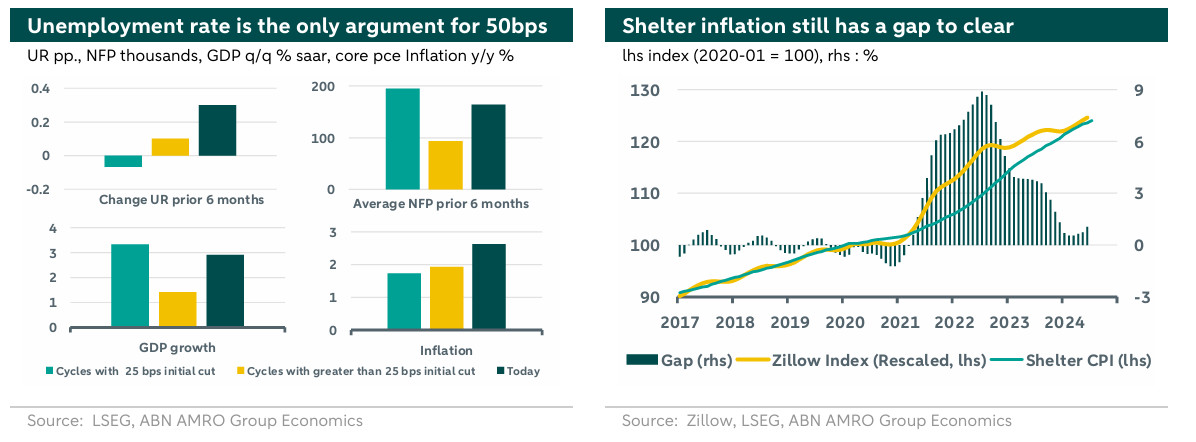

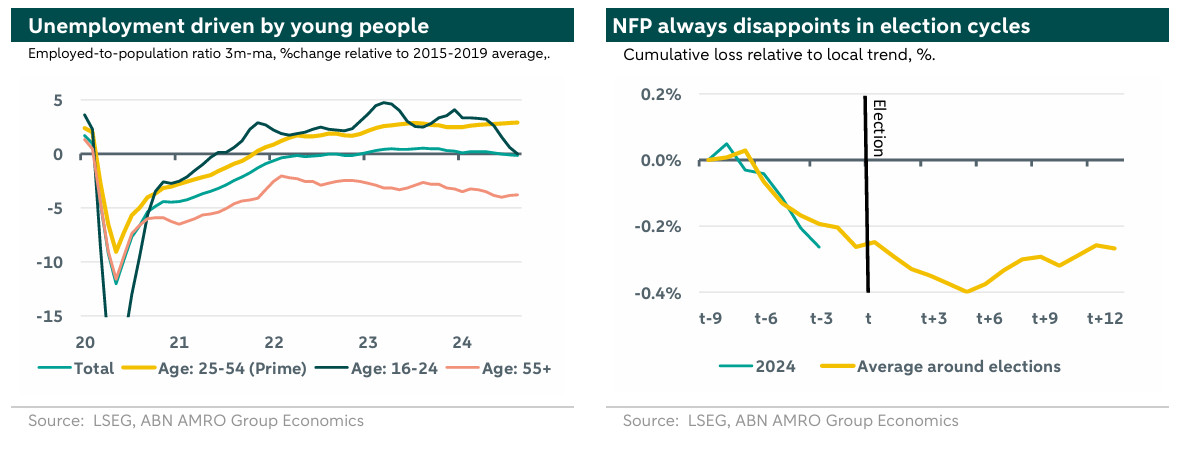

To understand whether the Fed is behind the curve, we summarize the state of growth, inflation and the labor market at the start of the five easing cycles since the 1990s, split by 25 and 50 bps initial cuts. First, and not unimportantly, in previous easing cycles inflation was typically not above target. August core CPI surprised to the upside at 0.3% m/m, predominantly driven by another high shelter inflation reading. Zillow data until July suggested Shelter CPI still had about 1% of price increases to catch up to. The large August reading has reduced that gap a bit, but it will take some months for shelter inflation to return to pre-pandemic levels. GDP growth and gains in non-farm payrolls resemble the levels seen in the typical 25bps initial easing, while the unemployment rate has increased decidedly more rapidly than during the onset of any of the previous easing cycles. We have previously written about the fact that the current rise in the unemployment rate is unconventional, in the sense that it is more supply driven than usual, with only a limited role for a decline in demand. This is further corroborated by the fact that as a percentage of the total population, employment has stayed quite stable, and could easily be interpreted as ‘full employment.’ The rise in the unemployment rate therefore partly stems from in an increase in the participation rate. The rise also reflects a more worrying trend for young workers, aged 16-24, whose employment to population ratio has decreased by 2.7 p.p. since the start of the year, although it is still at its 2015-2019 average.

A confounding factor is the fact that we are in an election year, and as we’ve demonstrated before, the economy tends to slow down in the quarter before the election in the face of uncertainty on future policy plans. Here we add to that analysis by considering the behavior of non-farm payrolls (NFP) around election years. The chart on the right shows that NFP always slows down relative to the previous year’s trend in the period prior to elections, and only slowly recovers in the year after the election. The current softening is slightly stronger than the average over previous election cycles, but generally in the same ballpark. Indeed, survey evidence generally points towards economic uncertainty as the primary reason for the weaker labor market. While the Fed is unlikely to call out the election as a reason for weakness in recent labor market data, it is clear that the potential impact of the candidates plans can be large. It is not surprising that firms might be more cautious in hiring with the election outcome still a toss-up.

The underlying fundamentals of the labor market are not as weak as the increase in headline unemployment would suggest. We therefore see little evidence of the Fed being behind the curve, and we expect the Fed to start the easing cycle with 25bps on September 18th.

How aggressive will the easing cycle be?

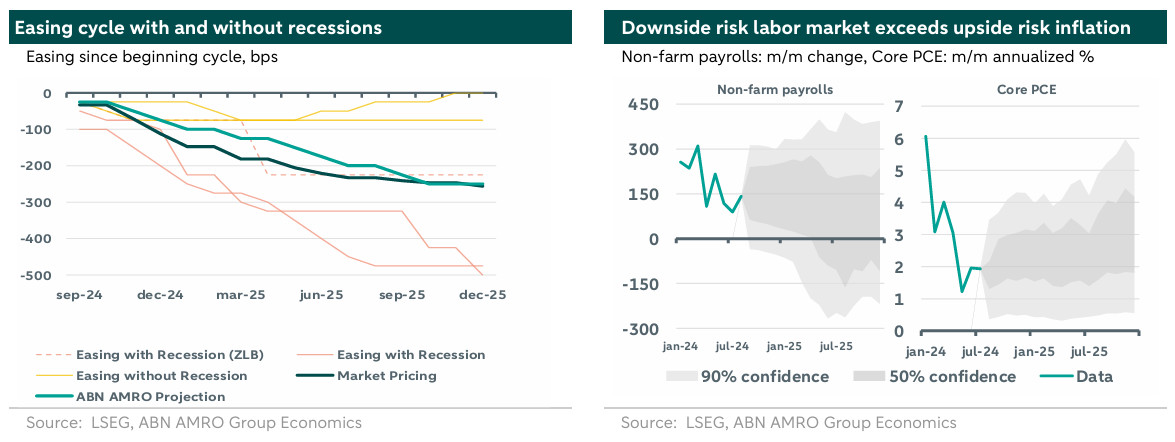

Previous easing cycles can broadly be categorized as in response to 1) a recession, and 2) tight policy simply no longer being necessary. In case of the former, easing cycles are aggressive, with cuts of up to 150 bps per meeting, easily reaching 300 bps in a year. Easing cycles that did not come with a recession were rare and short - soft landings are a rare event – with the easing process stopping after 75 bps. The 2024 easing path is unlikely to mirror either of these two scenarios. It is clear that the current market pricing, similar to our own base path, implies a soft-ish landing, as a recession would require the Fed to put rates in accommodating territory. Indeed, we still assess the probability of a soft landing to be higher than that of a hard landing.

The pace of easing will depend on incoming data on both sides of the mandate. Higher inflation readings will slow the pace, while weak labor market readings will increase the pace. Headline figures for the labour market data releases have disappointed in the past two months, and may continue to disappoint until some of the policy uncertainty resolves. In any case, the Fed will take the 25 bps or larger meeting by meeting, and a single datapoint will not fully determine this decision. We do not expect a sequence of inflation readings that will force the Fed to stop easing, which leads to a lower bound on the pace of 25 bps per meeting until neutral. As the chart on the right above shows, the risk of a sequence of disappointing labor market data is higher, especially considering the economic policy uncertainty induced by this presidential election. This raises the probability of a ‘jumbo’ cut of 50 bps in either November or December. It would be politically sensitive for the Fed to explicitly call out election uncertainty as a reason to take less signal from the incoming data, but election uncertainty is an unavoidable factor to consider. As a result, for now, we refrain from projecting a steeper path. Importantly, the path to neutral assumes a lack of large shocks that may steer the economy off course. There is however extensive scope for such shocks to materialize, due to for instance the election outcome, or geopolitical risks escalating.

We do not see a strong deterioration in economic activity over the medium term in our baseline, giving the Fed little cause to accelerate the easing cycle beyond the 25 bps per meeting. However, the risk of a deterioration in the labor market exceeds the risk of inflation picking up, making an acceleration more likely than a deceleration.

Fed-Speak: How do board members interpret the data

The FOMC’s blackout period started last Saturday, meaning we will not receive further guidance from FOMC members, particularly on how they view the latest labour market and inflation figures, ahead of next week’s FOMC meeting. There were two appearances after the August labor market report. Williams spoke a few minutes after the data release, and merely confirmed that it is now appropriate to lower rates, but emphasized he needed to have a closer look at the data before deciding on any further details. Waller, one of the more hawkish board members, spoke a few hours later.

Waller’s speech gave important information to market participants, but also to the Fed in terms of how much markets may be spooked by aggressive easing. He stated that the latest data ‘no longer requires patience, it requires action.’ Markets immediately reacted to such forceful language from one of the hawks, and moved towards pricing a 50 bps cut in September. The S&P immediately rose by 0.5%, before undoing the gain over the remainder of the speech, as his messaging reverted back to the usual hawkish tone. He stated that it was time to start the rate cutting process, but importantly, he also stated that if subsequent data shows a significant deterioration he would be open to more forcefully adjust monetary policy. This implies that he currently does not feel the data warrants larger rate cuts. In fact, he did not even commit to any future rate cuts, awaiting future data releases.

Other board members, that spoke before the labor market report, argued for a similar data-dependence, with their assessment on the near term differing along the dove/hawk spectrum. Goolsbee talked of steadily easing over the next year, implying multiple cuts over the next 12 months. Daly called for rate cuts to keep the labor market healthy, but emphasized that the size of the rate cuts is data-dependent. Bostic called the two mandates in balance, with the labor market continuing to weaken, but not yet weak.