US - A bull entered the China shop

The US economy showed remarkable resilience in the face of very restrictive rates. It is however increasingly showing cracks, with weakening consumption and labour market. Uncertainty about future policy is large, as is the range of potential outcomes.

The US economy again exceeded all expectations in 2024. At the end of 2023, the Bloomberg consensus forecast for annual growth was 1.2%; our own forecast was 1.8%. Currently we’re expecting 2.8% for the year. Despite high policy rates, and further passive tightening due to waning inflation, the economy showed even stronger growth than last year. The economy has been navigating the goldilocks zone, and is on course for that miraculous soft landing. Yet, 2024 was also very much a transition year. Headline growth has sailed on momentum from 2023, with both solid consumption and investment. But various pockets of weakness emerged over 2024, paving the way for a slowing down in 2025.

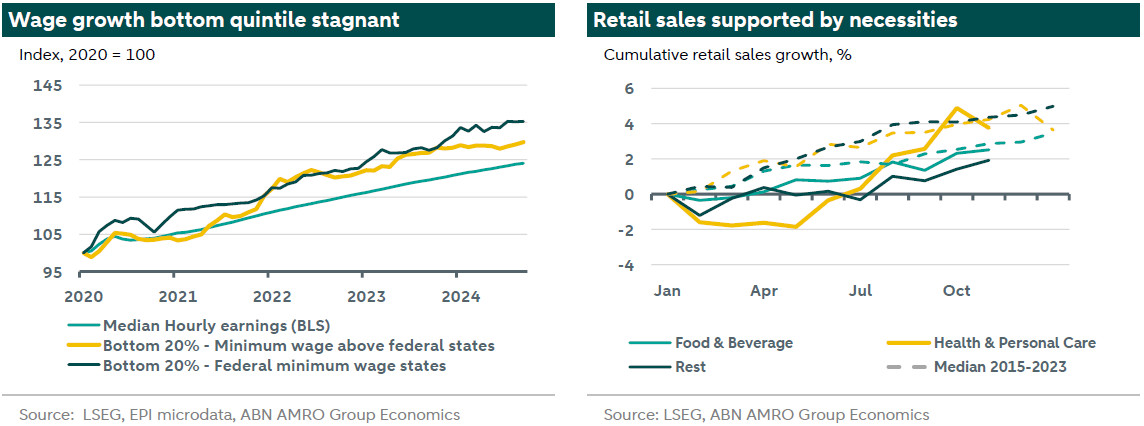

The first cracks in demand are showing. Real wages generally increased in 2024, but not for everyone. Since the start of the pandemic, the bottom 20% of wages showed substantially stronger growth compared to all other wages, breaking with a four-decade pre-pandemic trend. This was predominantly driven by the historically tight labour market, not increases in state-level minimum wages, where wage growth was actually weaker. As the tightness in the labour market receded over 2024, wages for the bottom quintile of the US population remained mostly stagnant, meaning a loss of real purchasing power. Excess savings have long been depleted for most of the population, the savings rate is at an all-time low, and consumption is increasingly supported by credit. In the aggregate, wage growth has outpaced debt growth; debt-to-income ratios have steadily declined. But as increasing levels of delinquency highlight, this is not broad-based. For credit card debt, 11.3% of the total balance is 90+ days delinquent (up from 8.2% in the beginning of 2023). Auto loan delinquency is similarly up to 4.6% from 3.9% in 2023.

Concurrent with the increase in credit delinquencies, we saw a change of pace in consumption, and particularly discretionary spending. Consumption growth is down to 1.9% from 2.3% at the same time last year, particularly due to much weaker growth in goods consumption. Indeed, retail sales shows a particularly weak year, with the slowest growth since at least 2015. Disaggregated data shows that consumption categories that are holding up are non-discretionary. Food and beverage, and in particular grocery stores have mostly kept up with historical trends, and health and personal care spending has caught up after a weak first quarter.

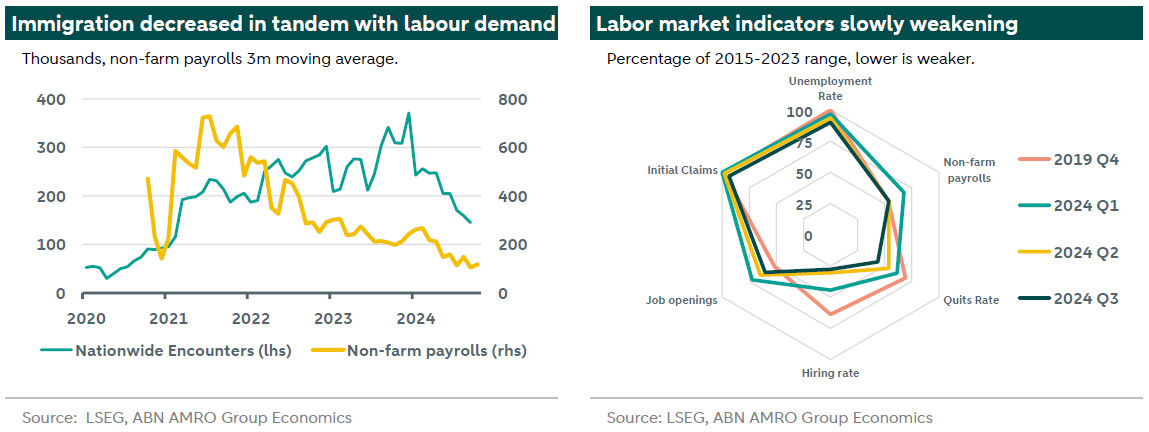

The labour market is similarly showing its first cracks. This year saw a trigger of the Sahm rule – a technical indicator that relates recessions to increases in the unemployment rate – leading to strong reactions in financial markets. This trigger was fundamentally different from previous ones, led by strong supply stemming from immigration, and a mere weakening, not contraction of demand. As the economy started to slow down, it had trouble absorbing the inflow of workers. We that the less certain prospect of a job in the US would reduce these strong immigration flows, and indeed, the number of border encounters has dropped significantly since the summer. This put less pressure on the unemployment rate, which has since mostly held steady since. Still, a broad set of indicators shows a slow but steady weakening of the labour market. The unemployment rate and initial jobless claims have increased but are still near historic lows. More granular measures of (un)employment generally show a labour market near full employment, . We see more weakness in non-farm payrolls, which have shown significantly weaker growth since the summer, and are consistently revised down. Job openings and the hiring and quits rates have seen a stronger decline, and are indicative of a less dynamic labour market. Workers no longer see positive opportunities to move jobs. The vacancy-to-unemployed ratio is nearing unity, a point at which unemployment may quickly take off. While the momentum was strong going into 2024, the momentum is in the wrong direction for 2025.

The second half of 2024 sets the stage for a further slowing down in 2025. As set out in the Global View, we expect the economy to continue to exhibit solid growth compared to other advanced economies, albeit at a below trend pace. The momentum will initially continue into 2025, although the potential of tariffs mean that frontloaded imports may obfuscate this in headline growth figures, via a drag from net exports. Over time, underlying demand will also slow down the economy more fundamentally, not least because of government-induced headwinds. We go into 2025 with a lot of uncertainty regarding US policy. The big open question remains when, and to what extent, the tariffs will be implemented. The details will be crucial in how the economy will develop. We’ve evaluated some alternative scenarios in the Global View. Beyond the tariffs, there are three additional crucial policy issues for which we will get greater clarity on in the course of 2025: the budget deficit, immigration and the Federal Reserve’s independence.

The establishment of a Department of Government Efficiency notwithstanding, the proposed policies are likely to push the deficit, and therefore the government debt level, up significantly. Nearing 100% of GDP, debt was already on an , and this is increasingly attracting attention. These worries may play a prominent role in passing deficit-increasing legislation, given the thin Republican majorities in Congress. Trump’s proposals would raise an already high deficit of about 6% to 9%, according to Committee for Responsible Federal Budgets estimates. Elon Musk has stated that the Department of Government Efficiency could remove $2 trillion from the budget – which would be enough to balance the 2024 budget – although it is not clear whether this would be in a single year or over multiple years. Current discretionary spending – spending that is not set in law - accounted for $1.7 trillion in 2023, so the $2 trillion target would be difficult to achieve in a single year. We ultimately expect the department to predominantly impact deregulation, rather than cost-cutting. Finally, a will help the budget in the near term, but will likely lead to worse budgetary and economic outcomes in the medium and long term.

Trump has confirmed he wants to use the military for active deportations by declaring a national emergency. They will target the more than 11 million people that are staying in the US with no legal basis, aiming for deportations of about 1 million per year. Deportations would require extensive funding, as well as cooperation from countries who have to accept the returned migrants. The government will likely also face legal challenges. If broader deportation is successful, the jobs they leave will be difficult to fill without significantly raising wages, and may even have knock-on effects in losing more jobs associated with them. The harder immigration stance is also likely to deter more potential migrants from attempting to enter the US. Immigration played a large role in alleviating worker shortages over the past years, dampening price pressures that might have otherwise occurred. While the labour market is less tight now, extensive deportation is still likely to increase inflationary pressures.

Trump and various members of his government that’s taking shape, have openly stated they believe that the Fed’s independence is not supported by constitutional law, and isn’t good for the economy. We have previously about a potential attack on the Fed’s independence. The Fed will face a challenging environment; Trump’s policies have the potential to increase inflation and decrease growth, pulling the policy rate in opposing directions. Rapid policy implementation may catch the Fed off-guard, meaning there is a high chance the Committee will be behind the curve. This will add to fuel to the government’s attack on interest rate policy. Powell has made it clear that he would not step down if asked. His term as chair runs until May 2026; his board appointment ends in early 2028. Even a demotion from Powell’s chair position seems unlikely, and a legal fight, during which he would maintain his position, will likely run beyond the end of his term. Changes to the Federal Reserve Act are unlikely. During the first Trump administration, various Republican senators blocked the appointment of Trump’s proposals for the Fed board when they deemed them unqualified. The financial sector and markets are likely to defend the Fed’s independence tooth and nail. Still, the appointment of Powell’s successor in 2026 will be crucial for the medium term monetary policy outlook, as the economy will still be coping with policy-induced inflation at that point.