Special - We need to talk about China…

(I) Reliance on China might be the least-worst of all options by Sandra Phlippen. (II) China’s growth impact on Europe – Supply hits even more than demand by Arjen van Dijkhuizen

(I) Reliance on China might be the least-worst of all options

Caught up in geopolitical tensions and warfare, Europe – a trade driven continent – needs to choose its battles if it wants to turn decarbonisation into a competitive advantage. If Europe turns its back on China’s offer to keep our energy transition affordable, decarbonisation can become a self-eroding force through either political retreat or through competitive disadvantages.

The goal of upping productivity – or suffering the of declining living standards – has become a dominant narrative among European policymakers, politicians and economists since Mario Draghi published his long-awaited report on Europe’s competitiveness. Most of the recipes in Draghi’s cookbook are about internal problems to fix, such as unnecessary and conflicting regulation, policy prioritisation and deeper capital markets so that Europe can join the technology revolution not merely as consumer and regulator, but also as a producer.

What did not need any fixing was Europe’s position as a global trading partner, as it is already one of the most prominent players in global trade. A position that has provided Europe the very basis of the wealth and welfare that it is so afraid to lose.

Trade openness as a liability?

Today, as the world is increasingly filled with trade-, and political conflicts, this trade openness feels more like a vulnerability than a strength. Trade openness no longer has the same lucrative allure as an aggregate , but seems to have become a naïve dream of global prosperity by armchair economists. Today’s global commodity chains are mainly cited for carrying risks of reputation-damaging ESG problems, importing cybersecurity threats, and – most of all – they are seen as making us dependent on regimes that can have significant influence over our institutions. Our answer: strategic autonomy.

Strategic autonomy – meaning industrial policies promoting home production or, at least, near-shoring production in strategic sectors – has become Europe’s main policy response since it started doing the rounds in Brussels thinktanks. This began in 2016, when the trade war between the US and China broke out and threatened to involve Europe. The Russian invasion of Ukraine gave the need for strategic autonomy in energy a whole new meaning. The latest push came from Trump’s announcement of steep tariff walls on China imports that induces European fears of a China shock 2.0, with cheap products flooding the continent and driving European businesses into default.

Openness ≠ vulnerability

Trade vulnerability or trade dependence can be assessed via impact (Europe’s reliance on certain products) multiplied by probability (the potential of a trading partner to squeeze our access to a product). According to an , most imported products do not make Europe more vulnerable: we can either live without them, or we can diversify our purchases to other suppliers. Besides the obvious critical products such as life-saving pharmaceuticals, and physical, digital and energy infrastructure that form basic safeguards, there are therefore many good reasons for keeping trade relations with China open.

Energy independence comes from low system costs

Energy independence became a desired outcome since the Paris agreement of 2015, but it wasn’t until 2022 – when reliance on Russian gas was no longer an option – that it became a necessity. With that, the energy transition which already carried many risks of price increasing hurdles when gas was still a transition fuel, suddenly became much bumpier and more uncertain. The costs of renewable energies such as wind, solar and battery technology decreased massively, but this has not yet solved the problem of the inherent uncertainty of these technologies. Investor appetite is hampered by volatile and hard to predict future cash flows. Also, the interest rate rises of 2023 and 2024 hit investments in renewables disproportionately hard, as these require relatively more upfront capital investments.

All of these factors have increased the energy systems’ total costs. And while the basic grid investments are part of a strategic autonomy agenda, the products that tap into the grid (EVs, panels and batteries) are not.

Low system costs come from trade openness

Electric Vehicles, batteries, smart demand managing appliances and of course solar panels should be sourced from global markets, or at least through European green field investments by the most efficient suppliers. It is the best way to prevent the transition from becoming unaffordable for consumers, which would in turn make politicians reluctant to introduce further transition-inducing policies. Also, European manufacturers need the cheapest possible energy costs to win back the competitive position they started losing since the energy crises. Openness to Chinese imports even benefits critical infrastructure investments indirectly, as the inflation-suppressing effect of cheap products enables interest rates to stay low. This further strengthens the case for large European investments in critical infrastructure.

Negotiating power for European values

The first worry people have when hearing about cheap Chinese products is that European values are trampled on to make these products so cheap. The new geopolitical order offers opportunities to do something about this. China’s necessity to find a market for its overcapacity can be a strategic advantage for Europe to demand production conditional on human rights or European jobs. This week’s news on by the EU toward accepting production bids from Chinese battery production signals that Europe is learning fast.

(II) China’s growth impact on Europe – Supply hits even more than demand

In the past, Europe’s growth link with China was primarily via demand, i.e. through the impact of Chinese demand on European exports. But, increasingly, China is competing more directly on Europe’s domestic home markets. This shift has profound implications for how we look at and assess China’s growth impact on Europe.

The shift in the relative importance of these demand and supply channels is shaped by developments in China. Barring fluctuations related to the business cycle or big shocks like a pandemic, China’s growth rate is on a gradual slowdown path. China’s growth trajectory over the past few years has been impacted to a large extent by industrial policy focusing on the supply side (as Beijing wants to develop high-tech manufacturing), and the downturn in the property sector pushing down demand. Hence, China’s recovery is quite imbalanced, with the supply side stronger than the demand side (although with some signs of a recent demand revival – see China coverage in this Global Outlook). Domestic demand management has long played only a secondary role, gaining more attention only recently as China’s growth momentum kept stalling. Against this background, we distinguish two channels through which China’s growth trajectory is impacting the eurozone: the channel of China’s demand and the channel of China’s supply (although both channels are to a certain extent linked).

The channel of Chinese demand

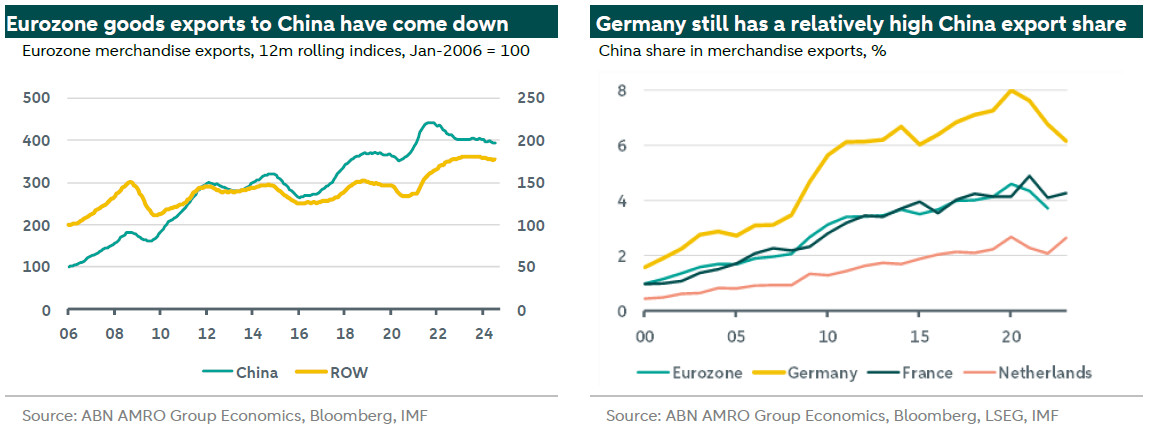

We analyse this channel by looking at eurozone exports to China. After having been on a sharp upward trend since the start of this century, with a clear pick-up during the initial phase of the pandemic (2020-21), eurozone merchandise exports to China have been on a downward trend in recent years. They started falling since 2022, when China was faced with broad lockdowns and the start of the property sector downturn, and have underperformed compared to eurozone exports to the rest of the world in this period. As a result, China’s share in eurozone exports peaked in 2020 at 4.6%, and has come down since. For Germany, which structurally has a higher China export share than the eurozone average, this share peaked at 8.0% in 2020 and has fallen even sharper. This drop in eurozone goods exports to China can be explained in the first place by the general weakness in China’s domestic demand, particularly in construction related sectors. However, this also seems to reflect a shift in Chinese consumer preferences, for instance in new tech areas such as electric vehicles – with domestic supply being cheaper and at least equal in quality (also see below). Finally, it will likely also reflect the rotation in Chinese demand back to services after the pandemic.

The channel of Chinese supply

While demand remains an important channel, China’s impact on Europe through the supply channel looks even stronger. China has rapidly caught up in terms of innovation and its move up the value chains, supported by Beijing’s industrial policies aimed at bolstering strategic, emerging industries. US import tariffs also look to have contributed to a shift towards higher value-added, less price sensitive sectors. As a result, the composition of China’s exports has become more similar to that of developed industrial nations. What is more, China’s competitiveness has benefited in recent years from the fact that it did not experience a severe energy crisis driving up inflation and wages, unlike many of its competitors (see our May 2024 Global Monthly on eurozone productivity ). In fact, domestic demand weakness and the resulting deflationary pressures has made China even more competitive in this respect, while adding to domestic oversupply. As a result of all of this, industrial countries, including in Europe, are faced with cheaper, but (at least) similar-in-quality, competition from China in domestic markets, and with more serious competition with China in third markets. This has contributed to an intensification of trade spats between China and the west, including the EU (see our on global excess supply driven by China and our ).

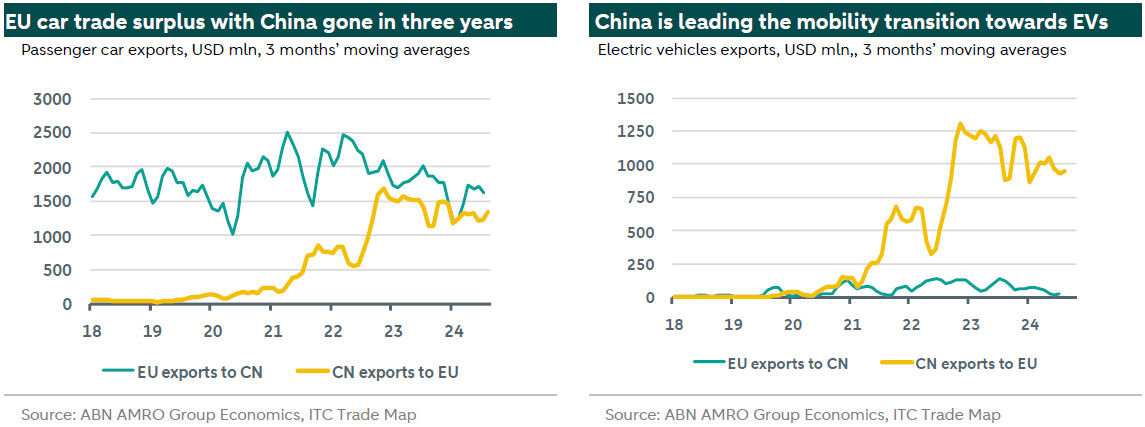

A clear case in point: the car sector

Europe, and in particular Germany, looks particularly exposed to China’s move up the value chain, given that it increasingly has a high export similarity with China. Developments in the car sector probably offer the most striking example, with China overtaking Japan as the world’s largest car exporter in 2023. In 2018-2020, the EU still had a large trade surplus in passenger cars with China, but this has almost evaporated in recent years. As the chart below on the left shows, that is driven more by the rise of China’s car exports to Europe (the supply channel) than by the decline of EU’s car exports to China (the demand channel). All of this is largely explained by the fact that China is leading the global mobility transition towards electric vehicles (EVs): China’s EV exports to the EU have surged since 2021, while the EU’s EV exports to China are still negligible (see chart below on the right).

Conclusion: Europe, please unite and innovate!

Going forward, we expect China’s domestic demand to stabilise following the stepping up of monetary and fiscal stimulus, which should support eurozone exports to China purely from a cyclical perspective (eurozone producers of for instance luxury products may benefit). However, the more structural factors at play (shift in preference of Chinese consumers, rise of China as strategic competitor on European and third markets) are unlikely to reverse soon, and this may continue to form a drag for the eurozone economy for the foreseeable future. The EU has reacted so far to China’s oversupply with a stepping up of trade restrictions, with the proposed hike in EV import tariffs (from 10% to maximum 45%) being the most eye-catching example. China retaliated with tariffs on European brandy, and is investigating pork, dairy and cars. With tariff negotiations still ongoing, we still do not believe the EU and China will run into a broad tariff war, comparable to the US-China one. Strikingly, Germany – the country most impacted by China’s rise – has voted against the EU EV tariffs, with Germany’s car lobby strongly opposed.

More generally, we think trade tariffs are not really effective in addressing the root causes of the problem. A more effective, sustainable route for Europe would be a joint stepping up of investment in innovation, and a stronger integration of knowledge, competition, trade, industrial and security policies – in line with the recommendations of the Draghi report (see our earlier coverage ). Given the way the political winds are blowing in Europe right now, an integrated EU approach looks unlikely in the near-term, though the German federal elections (see coverage in this Global Outlook) may lead to a shift at the domestic level. In the meantime, European industry should get used to no longer seeing China as the growth driver that it used to be.