Global Monthly - What’s up with eurozone productivity?

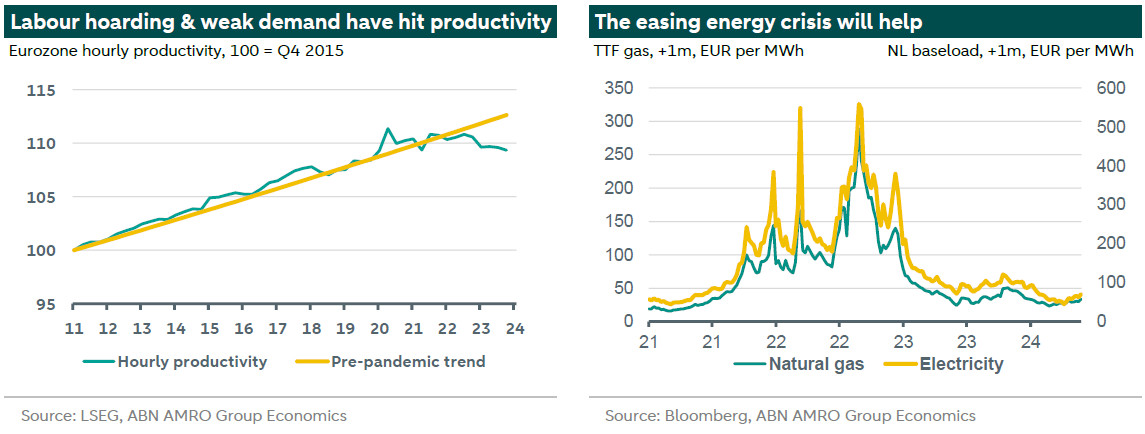

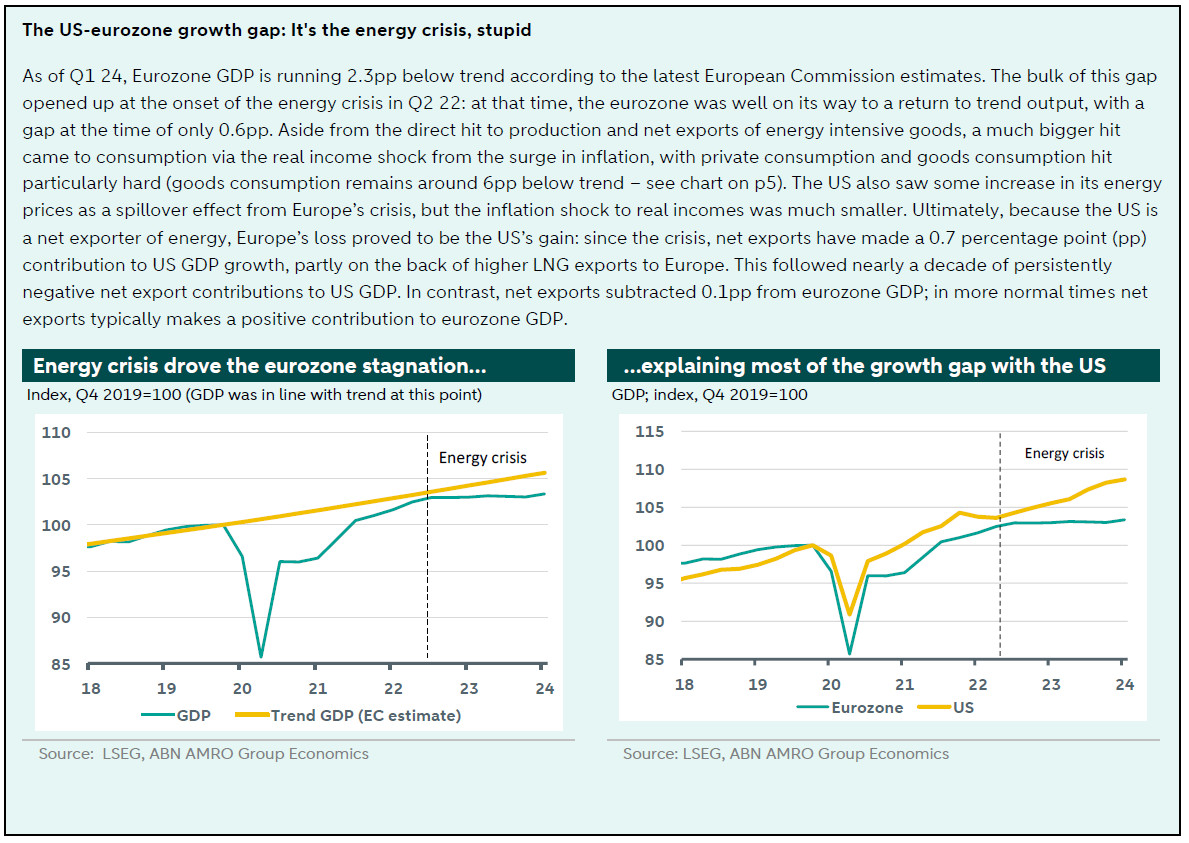

The eurozone has long faced a productivity problem, but recent years have been particularly worrisome. Structural headwinds, from weaker technology diffusion to the imperfect single market, are expected to continue weighing on the medium term productivity outlook. However, the easing energy crisis – which is responsible for the bulk of the weakness recently – is likely to drive a cyclical improvement in the near term. This should help close some of the growth gap with the US over the coming year.

Global View: The easing energy crisis should give some lift to eurozone productivity

The ECB looks almost certain to kick off its easing cycle next week Thursday, in what must be one of the most heavily telegraphed policy pivots in recent history. At the same time, financial markets seem to have already got used to the idea that the Fed and ECB policy paths are about to diverge – a prospect that looked unlikely only a few months ago, before US inflation sprang an unwelcome return. The reason markets are digesting this development so well are twofold. First, markets continue to think the Fed will not be all that far behind the ECB in lowering rates. In other words, the divergence is not expected to last very long. And second, there are good reasons for the policy divergence. Despite tentative signs of a recovery so far this year, the eurozone economy continues to be in a much weaker state than that of the US economy, and combined with the further falls in inflation we have seen, this gives the ECB a greater urgency to lower rates than the Fed. But will the eurozone continue to significantly underperform the US this year? We have long expected 2024 to be a year of transatlantic convergence in growth trends, with the US economy coming back down to earth, and the eurozone recovering from a prolonged period of stagnation. This view hinges on a recovery in eurozone productivity, which has been so poor recently that it is drawing the attention of , former Italian prime ministers. In this month’s Global View, while acknowledging the structural challenges the eurozone faces, we make the case for the further easing in the energy crisis – alongside reduced labour hoarding – to drive a partial recovery in productivity this year.

Eurozone productivity: Bad track record aggravated by the energy crisis

The eurozone does not have a great track record when it comes to productivity. While productivity growth has slowed , long term productivity growth in the eurozone has lagged the US since the start of this century. Some of the reasons for this are specific for the eurozone; others are global in nature. To name a few: 1) changing sector compositions (increasing share of low productive services); 2) low investment due to opaque capital markets in the eurozone, and from lack of scale for eurozone businesses; 3) slower technology diffusion across businesses 4) an imperfect single market. Together, these factors help explain the ‘’, which argues that the eurozone, compared to the US, has failed to reap the full efficiency benefits of ICT technology, or as Nobel Prize winner Robert Solow once famously put it: ‘Computers are everywhere except in productivity statistics’.

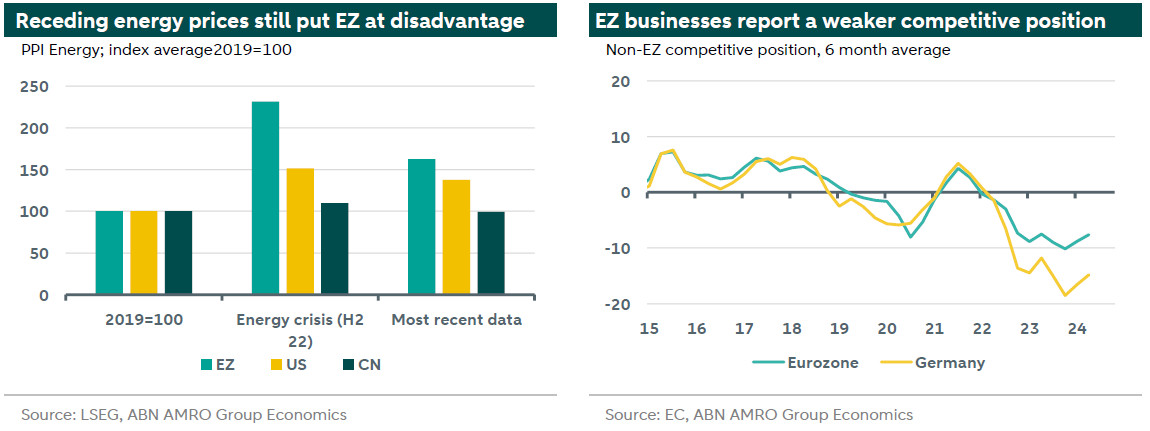

With a long term track record that is already subpar, recent crises – including the energy crisis and possible scarring from pandemic policies – have made things worse. Starting with the energy crisis, despite recent declines, eurozone energy output prices are still around 60% higher than pre-crisis, while in the US they are 35% higher and in China they are broadly unchanged. Next to energy prices, investment needs in grids – partly linked to the energy transition, but also due to the shift to LNG from pipeline gas – also pushed up costs. Elevated energy prices have hit countries with large industrial sectors particularly hard, like Germany and Italy. Of those two, as energy-intensive industrial subsectors such as chemicals and base metals are concentrated in Germany, the story of the energy crisis is to a large extent a German story. As a result of elevated energy prices, German producers in particular report that their competitive position on the global market has slipped, as input costs have risen more compared to global competitors.

Elevated energy prices: Short- and medium-term effects

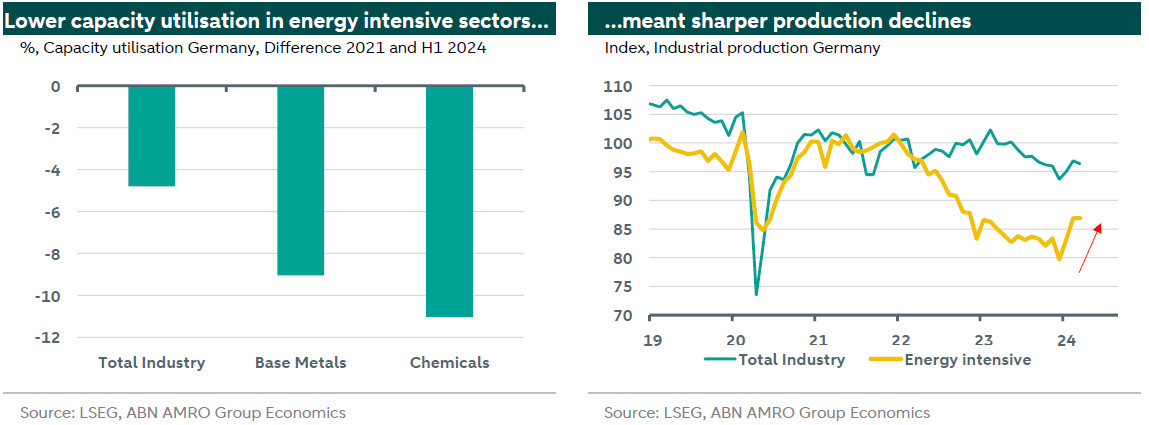

The link between energy prices and productivity is more complicated than meets the eye. The straightforward effect runs via capacity utilization. As energy prices rose, businesses shut down energy-intensive production. Examples of this over the past years are plenty: from the closing of a smelter in the Netherlands to chemical conglomerate scaling down production in Germany. Indeed, capacity utilization in Germany fell the most in energy intensive sectors when energy prices spiked back in 2022. While falling energy prices have since driven a pickup in energy-intensive output, these sectors bore the brunt of industrial production declines, and output remains well below the pre-crisis level. This could not have come at a worse time for the broader industrial sector, which already faced headwinds from the global manufacturing slump (linked to the shift in consumer demand from goods back to services).

As energy-intensive firms on average have a higher level of productivity, the hit to output has had an outsized impact on aggregate productivity figures. Furthermore, high energy prices have led to increased uncertainty over the viability of business models, which in turn can lower investment and thereby medium term productivity growth. It is too early to give definitive answers, but investment survey by the EIB suggest that energy costs are a major obstacle for investment for 60% of German firms.

Pandemic hangover: A blow to allocative efficiency?

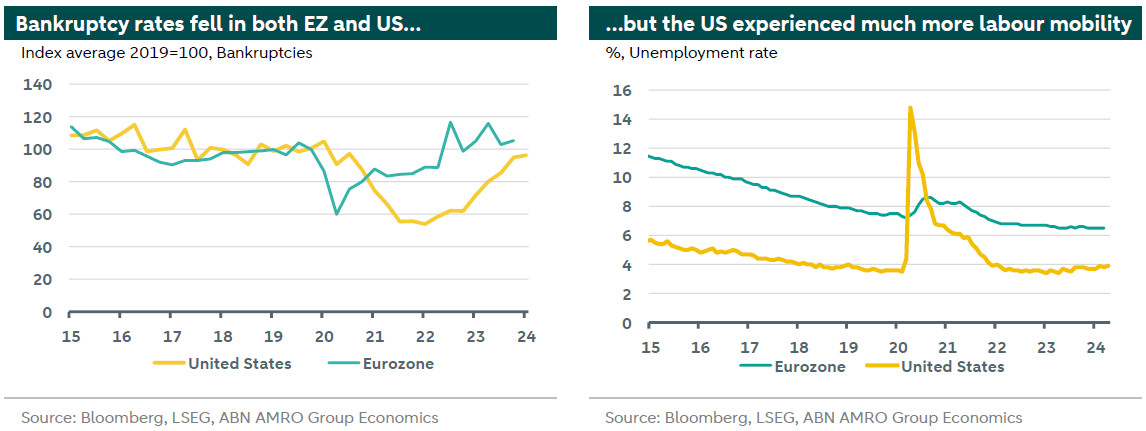

Productivity is traditionally viewed as having 1) a within-firm component, i.e. how productive is the firm, and 2) a between-firm component, i.e. can resources be allocated more efficiently between firms and thereby raising productivity? High energy prices primarily impact the within-firm component (1), but as by Dutch Central Bank Governor Klaas Knot, the pandemic may have impacted the between-firm component of productivity. Mr. Knot highlighted the differences in Covid support and the detrimental impact that may have had on labour and capital reallocation. Where the US supported workers directly as businesses laid people off, European governments favoured support via businesses (wage subsidy schemes). As a result, the supply side in Europe was ‘frozen’ temporarily, keeping employer-employee relations intact. Whereas government support in the EZ and in the US both lowered bankruptcies, labour mobility (looking at the unemployment rate) in the US was generally higher. While there is no clear evidence yet of any productivity effects of this, in the past, labour reallocation has been productivity enhancing. Judging from historical evidence, it is likely that increased labour reallocation in the US has also raised productivity this time – a benefit that the eurozone may have missed out on.

We expect a near-term bounce in productivity…

Productivity is often discussed as a longer run concept, but it also has a strong cyclical component. One of the main reasons productivity has been particularly weak over the past 18 months is that consumer and investment demand has stagnated, while employers – likely in anticipation of a recovery – have maintained or even expanded workforces. This combination has mechanically pushed down on productivity, and indeed it has surprised us the degree to which employers have held on to workers despite the weakness in demand (we had expected a decline in employment that has yet to materialise). Now that demand is recovering, we expect businesses to accommodate this by better utilising existing workforces rather than by further expanding employment or hours – both of which are already at historic highs. The catch-up in nominal wages with inflation – which is now weighing on profit margins – is likely to be an important factor that keeps employment growth in check. Our base case for the labour market therefore sees employment broadly holding at current levels, with GDP growth expected to continue recovering as the year progresses. This should raise productivity from a cyclical perspective.

…as businesses make better use of existing spare capacity

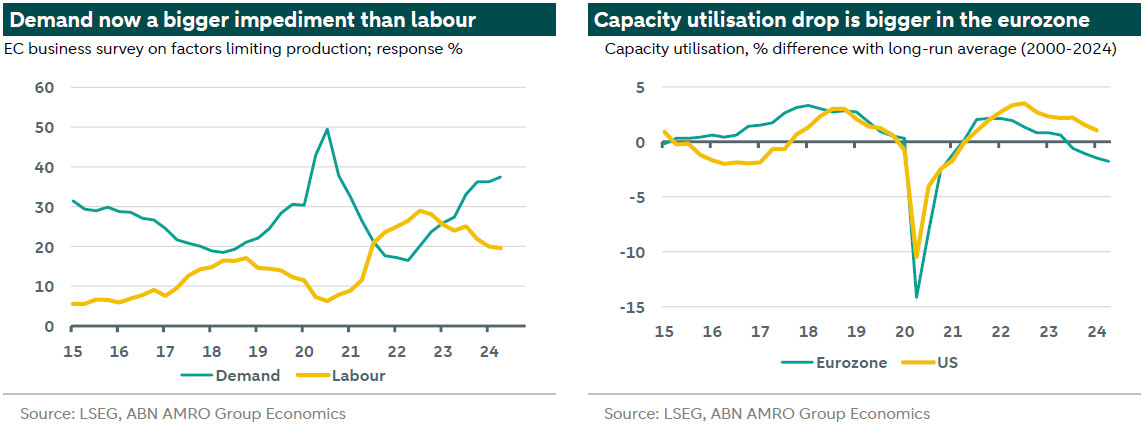

A clear sign that the existing workforce is not being fully utilised is the low level of capacity utilisation, which – at 78.9% as of Q2 – is the lowest rate since Q4 2020, when the economy was still recovering from the first lockdowns of the pandemic. While US capacity utilisation has also fallen back, reflecting tight monetary policy and the global shift in demand from goods to services, the fall in the eurozone has been much larger (-3.9pp vs -2.5pp in the US). We attribute much of this difference to the impact of the energy crisis, which has hit energy intensive industry particularly hard, as well as consumption more broadly via the shock to real incomes. The outsized decline in capacity utilisation in the eurozone suggests significant room for demand to increase without a corresponding rise in employment, which should partly reverse the recent decline in productivity. Another factor that should help is that the improved supply-demand balance for labour should lead to less labour hoarding behaviour on the part of employers. Indeed, the European Commission’s business survey on factors limiting production continues to rank weak demand higher than lack of labour as the main factor, and this gap has widened further in recent months.

Demand recovery to be driven by rising real incomes and reduced consumer caution

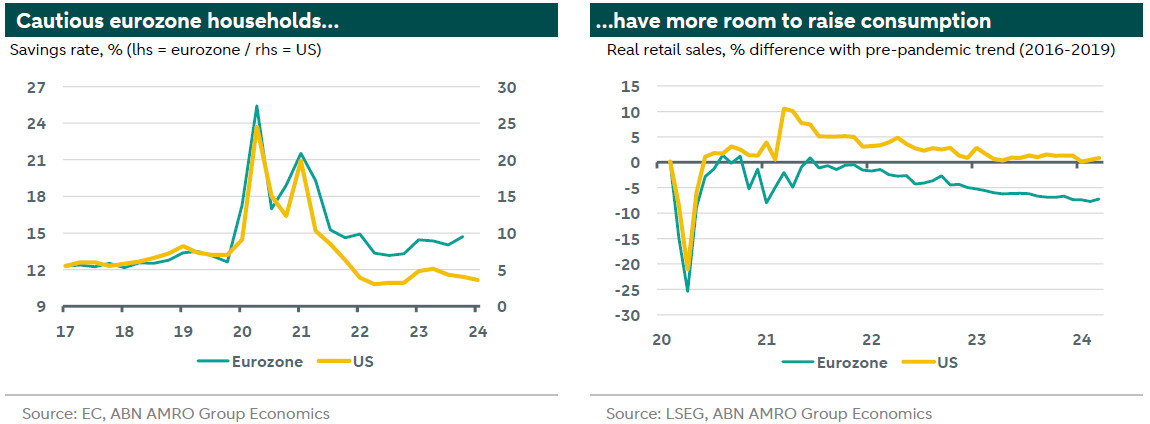

What will drive the recovery in output and demand? First, energy prices – while remaining higher than before the energy crisis – have fallen to more normal levels, and this is already driving some recovery in energy-intensive industry (see bottom right chart on page 2). Second, rising real incomes, driven by the aforementioned fall in energy prices as well as higher nominal wage growth, should support a recovery in goods consumption, which remains well below the pre-pandemic trend. Consumption is also likely to see support from a decline in the savings rate, which – in contrast to the US – has been higher than before the pandemic, suggesting eurozone consumers have been significantly more cautious. Rising real incomes and falling interest rates are likely to drive an improvement in consumer confidence, leading to a lower savings rate and therefore stronger consumption.

Still, we do not expect a dramatic rebound

Taking a step back, the energy crisis had a much milder impact on the economy than most forecasters (including ourselves) predicted at its onset. The eurozone economy has flatlined over the past 18 months, but it avoided a deep recession. And a silver lining is that high energy prices provided a spur to the energy transition. By accelerating the shift away from fossil fuels and investing in energy efficiency savings, European countries frontloaded some of the transition pain that will ultimately contribute to future-proofing the economy (2).

Still, while the easing in the crisis means we are likely to see some cyclical improvement in productivity, the same factors that weigh on the broader growth outlook are also likely to prevent a full return to the pre-pandemic/pre-energy crisis trend in productivity in the near-term. There is likely to be some scarring impact from higher energy prices (see page 2), and the structural move away from energy-intensive industry may create labour market frictions that take time to resolve (workers who lose their jobs in energy intensive industry may take time to re-train for other jobs). And it is not only energy-intensive industry that faces problems: the European car industry faces a major challenge from the shift to EVs, given the stronger competitive position of Chinese manufacturers. The expected raising of tariffs on Chinese EV imports by the European Commission – expected imminently – may guard against an existential threat to the European car industry, but this will not boost productivity, and may come with its own costs, for instance in the form of potential retaliatory tariffs on European car exports.

Meanwhile, though the policy proposals of Enrico Letta and the upcoming proposals of Mario Draghi show promise, the structural headwinds weighing on productivity mentioned at the beginning look unlikely to be resolved quickly. And though interest rates are expected to fall, rates are expected to remain at a level that continues to restrain demand for at least the coming year. Given these factors, we continue to expect near-term eurozone growth to remain below trend at 0.2-0.3% q/q, and even with above-trend growth expected next year, output is likely to remain below potential for some time yet.