ESG Strategist - Limited impact expected from the ECB greening its collateral framework

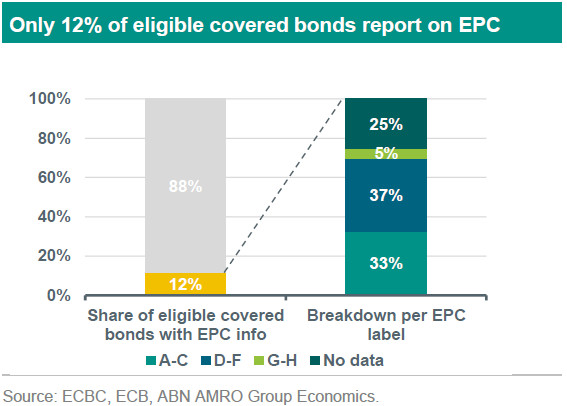

The ECB decided in 2021 to more proactively incorporate climate into its monetary policy strategy. This includes also the greening of its collateral framework. Until now, the ECB has only decided to (i) apply pool limits to corporate bonds that receive a high score by the ECB according to this framework, and (ii) limit the eligibility of marketable instruments and credit claims where the debtor is compliant with the CSRD. Our analysis indicates that these current measures would have limited impact on banks as only half of the credit claims refer to debtors that fall under the CSRD, and corporate bonds represent only 6% of assets currently pledged as collateral. We investigate how the ECB could potentially also apply climate-related criteria to covered and government bonds, but data availability remains a significant challenge. For example, for covered bonds, our analysis shows that only 12% of the eligible bonds currently report on the EPC label distribution of their cover pool. We also briefly discuss how green TLTROs linked to EU-Taxonomy assets could be a powerful instrument to lower funding costs for debtors in transition.

This article was written with the collaboration of Bernice Razenberg and Yu-Sha Vergeer, from ABN AMRO’s Sustainability Centre of Excellence

In 2021, the ECB conducted a review of its monetary policy strategy. Without prejudice to its first and foremost target – maintaining price stability -, the central bank also added climate considerations into its policy framework. Accordingly, the Governing Council has committed to an ambitious climate-related action plan (see ), which was also updated earlier this year (see ). Part of this plan was to introduce climate considerations as a requirement in the Eurosystem collateral framework (ESCF).

In this paper, we will examine the ESCF, including its purpose and current set-up. We then move to analyse the potential implications for banks of the ECB deciding to green its collateral framework. Lastly, we will discuss the possible introduction of a green TLTRO program as an instrument to assist on the climate transition.

What is the collateral framework and how does it work?

The Eurosystem collateral framework includes a wide range of collateral types in order to ensure sufficient collateral availability for a wide range of counterparties with different business models, operating in different markets. The complete list of eligible marketable assets is updated every day and publicly available on the ECB's website (see ).

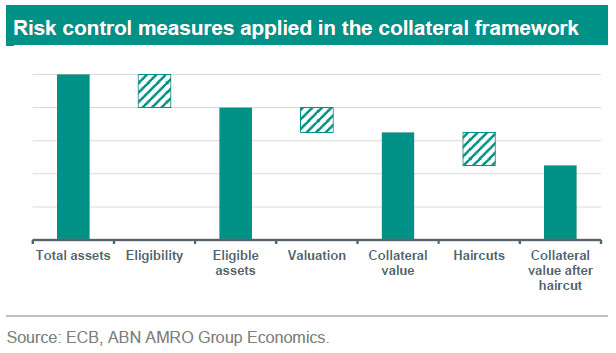

The collateral value is estimated based on four different risk control measures: counterparty and collateral eligibility criteria (which ensures operations are only conducted with financially sound banks and lent against adequate collateral), collateral valuation (which needs to occur on a daily basis for marketable assets) and valuation haircuts (depending on the asset’s credit and market risk, as well as liquidity). Haircuts are defined on an asset-by-asset basis, rather than on collateral pools, and do not differ per counterparty, in order to ensure a fair level playing field among market participants.

Even though the ESCF is not a monetary policy instrument per se, it may assist in the implementation of monetary policy. That is because the ECB can provide stability to the financial market by being willing to provide financing to banks on the back of collateralized assets. By doing so, the ECB can help to prevent solvent, but temporary illiquid, banks to default in the case of a financial stress situation. Ultimately, the collateral framework determines how easily banks can access central bank credit.

Additional to that, the ESCF also has indirect effects. For example, eligible loans under the ESCF provide a liquidity service to banks (the creditor). Research has shown (see ) that these banks have an incentive to pass on part of this benefit to their borrowers in the form of a reduced interest rate, which translates into lower funding costs for them. That being said, the ECB has already used the collateral framework as a tool to provide market liquidity in general in the past. For example, in response to the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, a general 20% reduction in the haircuts was approved in April 2020. A haircut reduction provides monetary easing with a direct potential impact on banks’ cost of funding. Such that, afterwards, it was argued that this was the first instance in which the ECB used haircuts as a monetary policy instrument (see ).

Which assets are accepted as collateral?

The assets accepted as collateral by the ECB are split into two categories: marketable and non-marketable. The first category includes government bonds and other debt instruments issued by public sector / supranational institutions, as well as own-use covered bank bonds (1), unsecured bank bonds, corporate bonds and asset-backed securities. Non-marketable assets include credit claims and cash deposits. With regards to credit claims, these include loans granted to the public sector, corporates, and small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Since 2011, member states can also set up country-specific additional credit claims framework, which specify the eligibility for additional credit claim (ACC) assets to be pledged as collateral. In this case, ACCs can also include loans to households as well as pools of similar kinds of loans, consisting of, for instance, corporate, SME, consumer loans or mortgages. Furthermore, following the Covid-19 pandemic, also loans backed by Covid-19-related public sector guarantees became eligible.

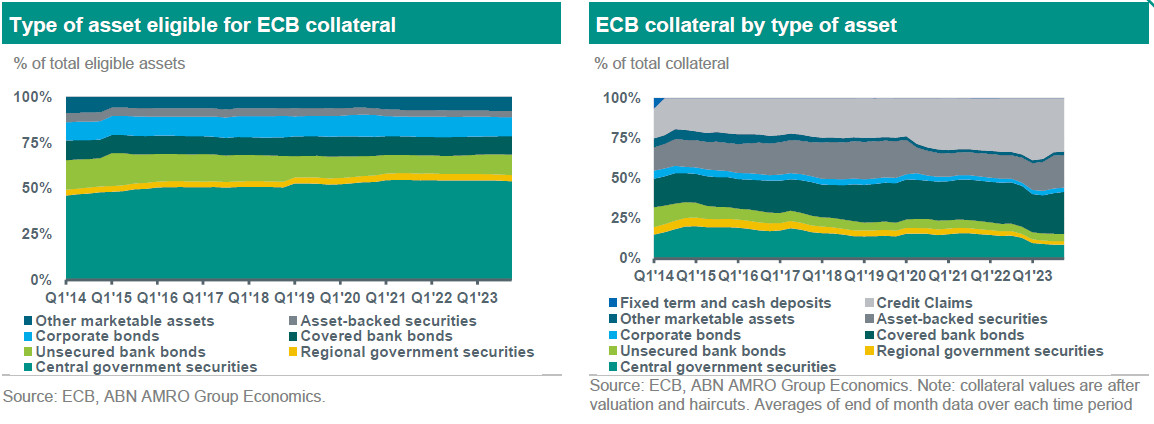

At the moment, there are EUR 18.3 trillion assets that can be pledged as collateral in the EU. The charts below highlight that, although the majority of eligible assets are in the form of central government securities (54%), the asset class most frequently used as collateral are credit claims (33%) and covered bank bonds (26%). This is because banks prefer to keep the most liquid and safe assets on their balance sheet. By doing so, banks can first use the most liquid and safe assets in case of liquidity issues, and only rely on ECB borrowings (backed by the less liquid collateral) as a last resort.

What would a green collateral framework look like?

1. Corporate Bonds

We think it is likely that the ECB will rely on the existing framework developed for the tilting of its corporate securities purchase program when implementing pool limits for the corporate bonds pledged as collateral. That is, there would be lower haircuts applied to corporate bonds that receive a high score by the ECB according to this framework. This framework consists of three pillars: (1) backward-looking emission performance of corporates; (2) forward-looking emission targets, and (3) the quality of climate disclosures. These pillars are used to compute climate scores, which range from 0 to 10, where the higher the score the better the climate performance of the issuer and the lower the haircut.

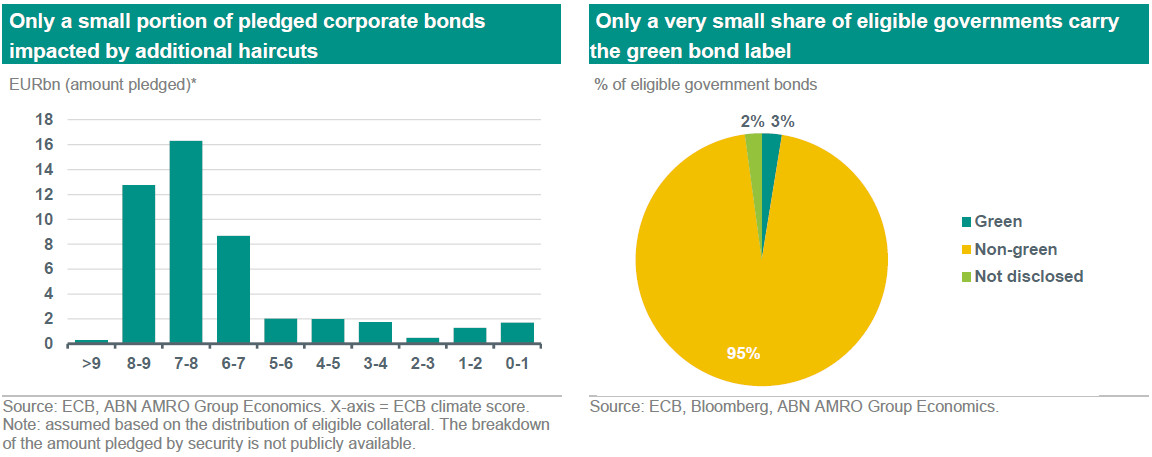

Based on our previous analysis of the CSPP (see ), we can attempt to replicate such scores in order to evaluate how many of the eligible corporate bond assets would be impacted were the ECB to apply higher haircuts to securities with a low climate score. While data is not fully available for the entire universe, our analysis is applicable to around 70% of all the eligible corporate bond assets, as per latest ECB data. As shown in the chart below (left), a large share of eligible assets is estimated to carry a high climate score. In fact, only around 15% of the assets carry a climate score that is below 5. If one assumes that the haircut would be applied in the form of best-in-class categorizations, as in - the haircut is split according to percentiles - the overall impact of the additional haircut could be minimal depending on the percentile considered. For example, a haircut distribution based on quartiles would imply that only the bottom 25% of the distribution (i.e. corporate bonds with a score that ranges from 0 to 2.5) would be severely penalized by the additional haircuts. Our analysis indicates that this refers to only 7% of the eligible universe. Applying that to the total collateral pledged in the form of corporate bonds would translate into an impact in only EUR 3bn of the total universe – a negligible amount compared to the EUR 1,137bn currently pledged as collateral.

2. Government Bonds

Looking at government bonds, the greening of this asset class in the Eurosystem collateral framework can be challenging. First of all, the ECB must be careful to not generate additional demand for certain European sovereign bonds by applying different haircuts based on, for example, climate performance, which may in turn compress yields and increase the spread differential across EU sovereign bonds.

Currently, the only differentiation in the collateral framework that occurs across countries is with regards to their credit rating (for example, countries with a credit rating between AAA and A- all receive the same haircut, assuming the same bond maturity). Second of all, were the ECB to discriminate countries based on their carbon emissions, an additional issue arises as there are several indicators that the ECB can consider for such assessment (for example, absolute emissions or emissions per capita). Furthermore, the emission disclosures per country at EU level occurs, as per , with a two year lag. This might also imply that a haircut based on emissions is wrongly penalizing countries that have already managed to extensively reduce carbon emissions over the previous two years. Lastly, the greening of government bonds might also impose several challenges from a political point of view. As just noted, higher demand (and hence, liquidity) for government bonds of certain countries can have a direct impact on a country’s funding costs, making this a politically sensitive topic.

Still, it is reasonable to include climate-related risks in the credit risk assessment (and hence, haircut) of a country – given that a country’s exposure to climate-related risks can impact the country’s capability of servicing its sovereign debt in the future. At the moment, there is evidence that ESG risks are not fully and consistently captured by credit rating agencies. Furthermore, the ECB itself has also noted that lower carbon emissions translate into lower credit risk (and vice-versa, see ). Hence, a reasonable alternative for the ECB would be to rely on more favourable haircuts to be applied on green bonds of government bonds. Or, another option, would be to increase haircuts on non-green sovereign bonds. Both alternatives would incentivize countries to increase the share of their green bonds over total issuance. At the moment, only 3% of the government bonds eligible for collateral hold a green label (see chart above on the right). Nevertheless, this could be seen as a viable alternative tackling the aforementioned challenges.

3. Covered Bonds

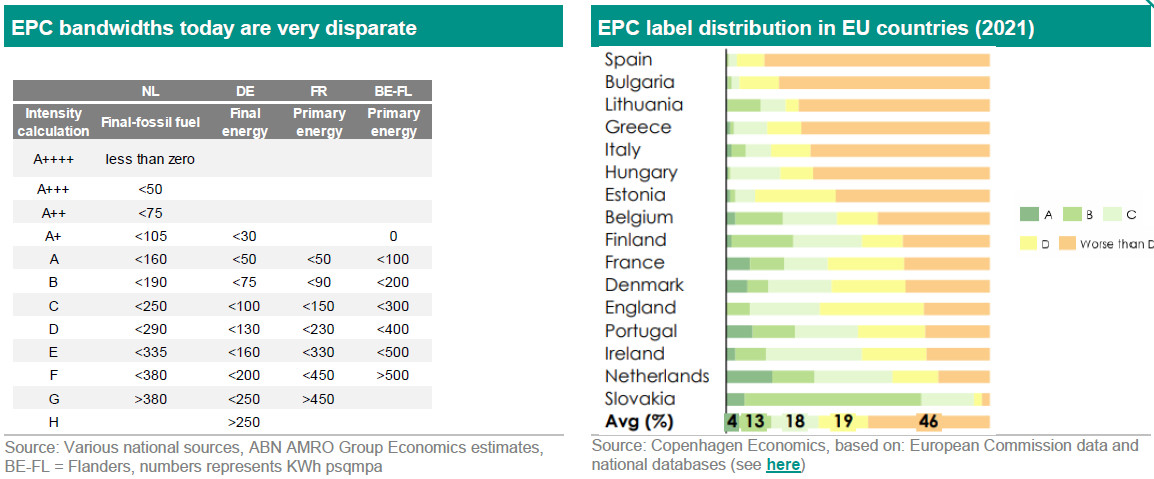

With regards to covered bonds, we think that the ECB will most likely assess the sustainability credential of the instrument based on the underlying assets. That is because the existing collateral framework assesses the riskiness of these instruments (and consequently, its haircut) based on the assumption that the value of these assets are ring-fenced from its counterparty. That being said, as covered bonds are usually linked to mortgages, we assume that the greening framework would be based on the energy performance of the underlying mortgages. This is currently proxied via the use of Energy Performance Certificates (EPC). One challenge arises however from relying on EPC labels for such assessment: the definition of EPC labels is very scattered around countries. For example, less than 160 KWh psqmpa (= per square metre per annum) implies an energy intensity that is equivalent to an EPC label A in the Netherlands, but only as an E label in Germany (see for example table on the next page). Hence, relying solely on EPC labels would perhaps unintentionally penalize some covered bonds exposed to certain countries more than others (see chart on the next page on the right).

To tackle this issue, the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD) was revised (the revision is expected to go through the formal adoption process in early 2024, see ). The revision included the harmonization of EPC labels, with energy performance classes expected to be based on common criteria. However, such harmonization is likely to take time. On top of that, not yet all buildings have an EPC label (this is only mandatory when properties are sold or rented). In fact, many of the covered bonds that currently report on the EPC label distribution, also report that a large share of the underlying buildings linked to the mortgages (around 25% according to our estimates, see chart below) do not have data.

An additional issue about relying on EPC labels to assess sustainability credentials (and hence, “green” the collateral framework) is the fact that not all issuers report on the EPC label distribution of the underlying mortgages included in the cover pool. For example, looking at the covered bonds that have a covered bond label granted by the ECBC (see - this represent around 70% of all outstanding covered bonds), only 16 out of 142 issuers report on the EPC label distribution of their cover pool. This translates to only 12% of the collateral eligible covered bonds having information available on EPC labels (see chart below). That would imply that, were the ECB to add additional haircuts to covered bonds that do not report on EPC label information (following the climate disclosures pillar of the framework applied to corporate bonds), a significant share of covered bonds would be penalized.

Overall, we think that a potential greening of the collateral framework involving covered bonds will only occur after the harmonization of EPC labels takes place and once there is more data available about EPC labels.

Important to highlight that the ECB has already acknowledged that the greening of both bonds issued by financial institutions as well as government bonds is limited due to data constraints. On this regard, the central bank affirmed that “additional asset classes [that is, excluding corporate bonds] may also fall under the new limits regime as the quality of climate-related data improves” (see ).

As of now, the only climate-related requirement applicable to these instruments and to credit claims, is that the debtors need to comply with the CSRD. As the implementation of the CSRD has been delayed, this eligibility criterion is only expected to apply as of 2026.

4. Credit Claims

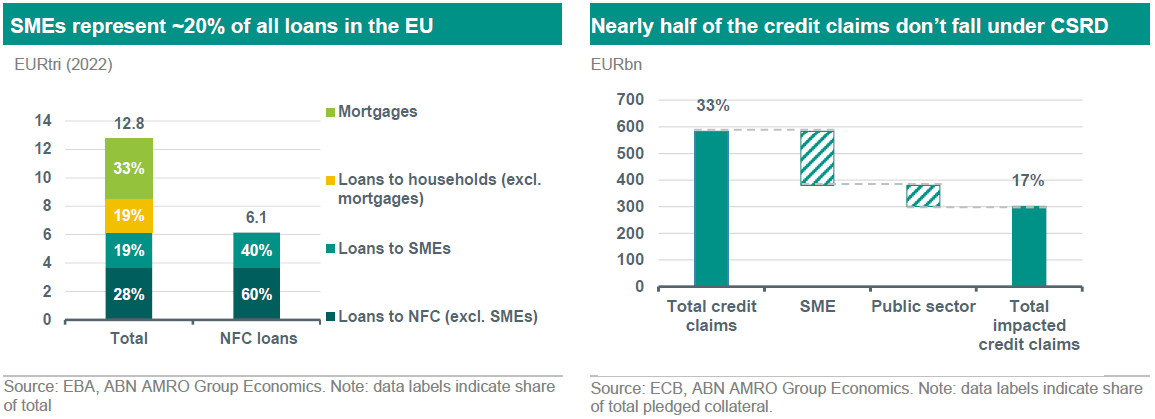

In this paragraph we will examine the impact of the CSRD-compliance requirement on credit claims. As we previously mentioned, these refer mostly to loans to corporates, SMEs and the public sector. Following the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic and the corresponding easing of some collateral measures, credit claims became an important asset for collateral purposes. As of Q3 2023, credit claims have the largest share (33%) of all the collateral pledged to the ECB.

Unfortunately, the ECB does not publish a list of eligible non-marketable assets, which makes the assessment of the impact of the ECB greening its eligibility criteria for credit claims very difficult. Nevertheless, it is possible to estimate how much of the pledged credit claims would fall under the CSRD-compliance criterion. That is because SMEs only need to comply with the CSRD as of 2028 (2) and public sector entities are out of scope of the CSRD. Hence, assessing how many of the credit claims are directed towards SMEs and public sector entities gives us a good idea of how large the impact of the ECB’s decision to green its collateral framework could be.

The European Banking Authority (EBA) estimates that SME loans represent around 40% of all non-financial corporate (NFC) loans in Europe (see ). Including also loans towards public entities (as per ECB data), this would imply a 35% share. That is because the ECB estimates that 14% of all loans (excluding financial loans) are directed towards the public sector (see ). Ultimately, that implies that only around 52% of all credit claims pledged as collateral would be impacted by the ECB’s decision to only accept credit claims from debtors that comply with the CSRD. This translates to an amount of EUR 260bn risking exclusion due to the new rules.

As a next step, we look at the expectations around CSRD-compliance. A study conducted by Lefebvre Sarrut, a provider of legal and tax services, showed that in June last year, 45% of the 744 surveyed European entities had not taken any action to prepare for the European CSRD directive and, what’s more, 43% did not have a designated reference for ESG criteria (see ). Still, the CSRD-compliance criteria under the ESCF will only apply as of 2026. Therefore the expectations are that, by then, the majority of the entities will comply with it.

What is the impact for banks in the EU of greening the collateral framework?

Banks pledging collateral in scope of the proposed changes may face a direct impact on their credit line with the central bank. Marketable debt instruments from non-financial corporations can be impacted due to limits on the share of assets issued by carbon-intensive entities that banks can pledge, or may become ineligible if these do not comply with the CSRD. This last limitation to eligibility will also apply to credit claims (non-marketable asset) from companies and debtors that do not comply with the reporting directive. Banks will either have to swap the collateral for assets that are eligible, or take a smaller credit line. In addition, liquidity may be reduced for banks that pledged collateral valued as weaker as a result of implemented haircuts aiming to remove the current carbon-bias from the framework.

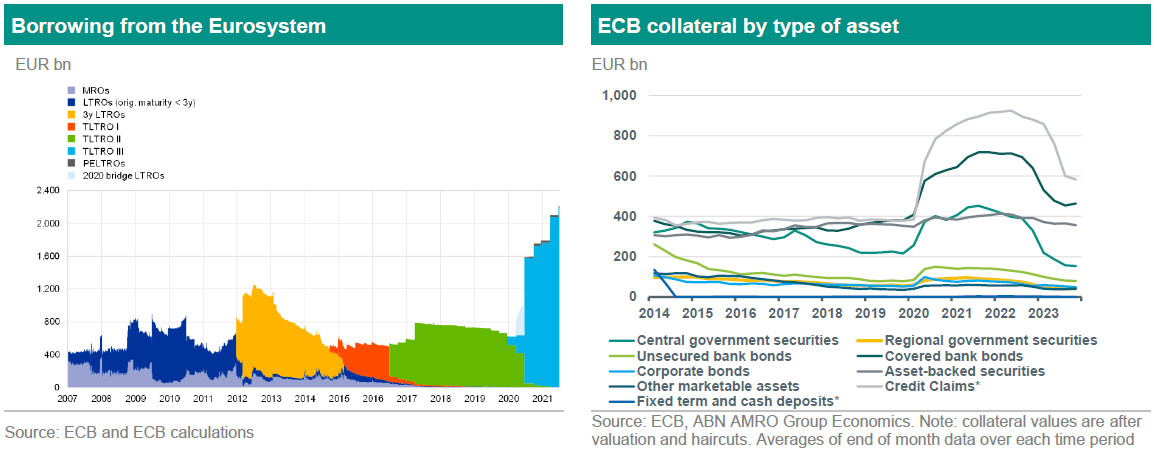

Although banks tend to start with the less liquid assets when pledging collateral, the composition of pledged instruments can change in future, as has occurred in the past. During times where central banks brought excess liquidity into the market (for example, via targeted longer-term refinancing operations, or TLTRO programmes, see chart below on the left) an increase in the pledged amount for particular asset types has been observed. Under TLTRO III, which took place in 2019, a sharp increase in the pledged volume of credit claims, covered bank bonds, and central government securities was registered (see chart below on the right).

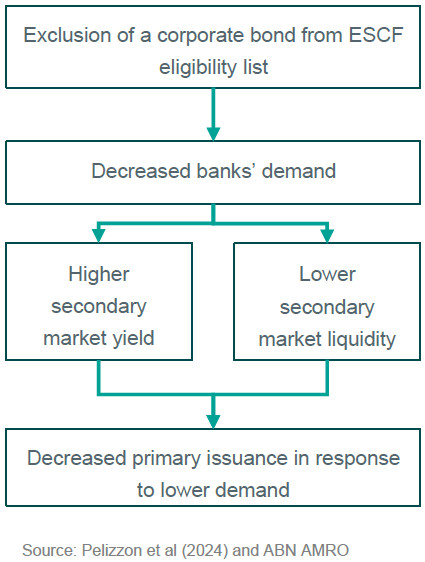

According to research (see ), there may be several knock-on effects observed as a result of the proposed changes to the framework. When the available credit line with the central bank is impacted by the greening of the ESCF, banks are likely to reshuffle their portfolios in response. Changes in the eligibility of collateral (marketable assets), specifically in non-financial corporate bonds, have a secondary and/or primary market impact on the asset (for example, via increasing/decreasing liquidity, bond yields and issuance). Overall, demand for assets that are no longer eligible under the framework will fall, resulting in a decline of the assets’ prices, and in the case of bonds, higher yields.

Exclusion from the ECSF eligibility list and its resulting consequences, as illustrated above for marketable assets, may increase the risk profile of the banks’ lending portfolio. As we just mentioned, changing demand for such assets could lead to reduced access to capital for these entities. This, in turn, has an upward impact on bond yields and consequently, on the debtor’s funding costs. Hence, one can argue that under a greening of the collateral framework, companies that are not compliant with the CSRD and/or that are not climate-friendly (as per the ECB framework), could experience a higher cost of funding. A higher cost of funding may have several negative financial implications, which, in turn, impact the riskiness of the borrower. As a result, banks may face increased credit risk on loans, with companies consequently facing an increase in capital costs following upward adjustments on interest rates when refinancing. If the higher cost of capital exceeds the cost to transform their activities, carbon-intensive companies are expected to transition their technologies towards more sustainable alternatives.

Prices and liquidity premiums for green assets, or assets of companies compliant with the CSRD, will increase, given the expected surge in demand and relative scarcity of such instruments. As a result, climate-friendly companies and companies compliant with the CSRD are expected to have a funding advantage.

Hence, the greening of the collateral framework incentivizes banks to shift their portfolios towards “greener” and CSRD-compliant assets This could lead to additional liquidity in green marketable paper. Moreover, as a result of changing demand in the primary market (and secondary for marketable assets), lending clients of the bank may be impacted by a change in availability of capital and the associated cost of funding themselves. This may lead to a second-order effect on banks of changes in the collateral framework, through changing solvency and credit worthiness of corporate loans on their balance sheet.

Green TLTRO: how would it work?

The Governing Council of the ECB developed non-regular refinancing operations, like the TLTRO, in order to strengthen monetary policy transmission. For instance, under the TLTRO, the ECB offered banks long-term funding at attractive conditions in order to stimulate bank lending to the real economy. As such, the ECB can also decide to make use of this tool to help the climate transition. For example, a green TLTRO programme would provide banks with cheaper funding if they lend towards green activities, which would help decarbonize the European economy.

There has not been yet any formal announcement from the ECB on intentions to green its TLTROs programme, which means that it is hard to foresee what a potential framework for green TLTROs could look like. However, one could argue that the main criteria will be to rely on alignment with the EU Taxonomy (3). That is because the EU Taxonomy’s goal is to “steer investments to the economic activities most needed for the transition” (see ). Hence, a TLTRO programme directly linked to more favourable interest rates directed towards green activities could be a potential route for the ECB to meet its objectives.

From this perspective, the interest rate that banks pay for the refinancing operations would be determined by the volume of Taxonomy-compliant loans issued by the bank. In practice, it should provide banks with a discount on their overall volume of interest payments to the central bank. That is, the green TLTRO rate should be lower than the regular ECB rate, so that banks which have no Green Taxonomy-compliant loans can only refinance at the regular rates. To enable an early implementation of Green TLTROs, however, the onus should be on banks to provide proper documentation for the Taxonomy-compliance of individual loans.

The challenge of applying such green TLTRO is the fact that only a very small share of banks’ lending activities currently align with the EU Taxonomy. A report by EBA (see ) estimated that, on average, only 7%-8% of banks’ assets complied with the EU Taxonomy. Nevertheless, such instrument could help increase this share going forward.

Concluding remarks

As the green transition becomes imperative and urgent, central banks start pondering what might or could be their role in the transition. The ECB has been a pioneer among central banks, by explicitly including climate change considerations in its latest monetary policy review. However, it remains unclear how will these considerations materialize. One of the options that the ECB has considered so far is to change the collateral framework of banks in order to accommodate climate change considerations. Until now, the ECB has only announced a framework to screen for the “greenness” of corporate bonds, and has announced that, as of 2026, it would only accept marketable instruments and credit claims from issuers that are compliant with the CSRD. Still, there are other asset classes that may be considered under these changes, like covered bonds or government bonds.

Looking at the current composition of assets pledged as collateral, there does not seem to be much impact from the ECB greening its collateral framework. That is because (i) corporate bonds represent only 6% of the total assets pledged, and (ii) CSRD-compliance requirements are only applicable as of 2026. With regards to the latter, our analysis also indicates that only half of the credit claims come from issuers that need to comply with the CSRD. Hence, also there the impact of such “green” measure would be limited.

With regards to green TLTROs, these could be powerful instruments to steer the climate transition in case the ECB offered banks lower rates for loans under the commitment that they use the proceeds of those loans to finance EU Taxonomy-aligned activities. Still, following a more hawkish monetary stance by the ECB since 2022, the use of these instruments could be dependent on a more accommodative monetary policy stance.

Nevertheless, the clear and increasing focus of the ECB of incorporating climate into its monetary policy strategy should be a strong signal to banks that the ones with a “greener” loan portfolio will benefit from a first-mover advantage as the central bank advances on its climate strategy.

(1) Own-use covered bank bonds differ from general covered bank bonds in the sense that they are not available on primary debt capital markets. The idea behind accepting covered bonds as collateral is that these assets do not derive their value from the financial institution, albeit being issued by one.

(2) This is also exclusively towards listed SMEs (non-listed SMEs are excluded from the reporting requirements).

(3) The EU taxonomy is a classification system establishing a list of environmentally sustainable economic activities to guide investments and lending towards a greener economy.