US - ISM and Manufacturing PMI divergence – what does it mean?

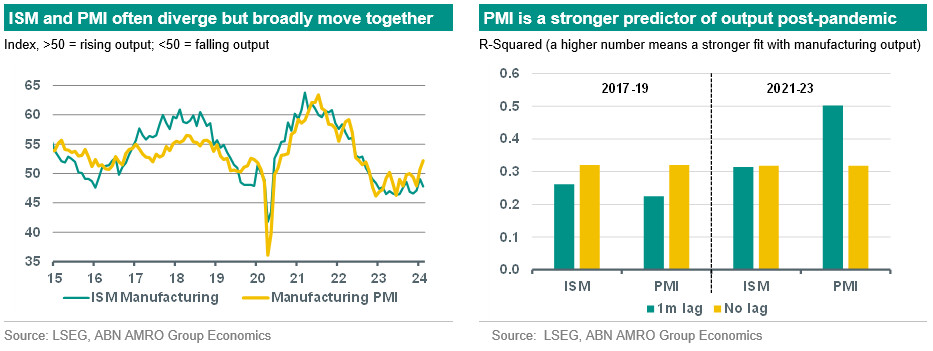

Last week, the ISM and S&P Global manufacturing PMI caught attention due to the notably divergent signals they were sending regarding the health of US industry. While the February ISM fell further below 50, to 47.8 from 49.1 – suggesting contracting factory output – the February manufacturing PMI actually rose 0.7 points to 52.2, suggesting rising output. What do these mixed signals mean for the US economy? And which index should we put more weight on?

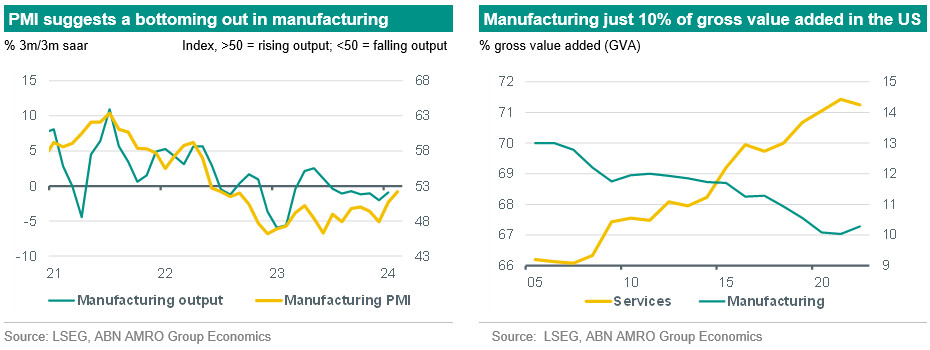

Looking through the noise, US manufacturing is bottoming out but not rebounding

We looked into the relationship between these indices and activity, and have two main takeaways. First, historically, although they tend to track one another very closely, we find it is actually not that unusual for the two indices to diverge significantly in a given month. It is highly likely therefore that this divergence will close again in the coming months (see chart below). Our second observation is that the manufacturing PMI seems to perform somewhat better as a leading indicator in the post-pandemic period, although both the ISM and the PMI are reasonably good predictors of manufacturing output. We therefore put somewhat more weight on the signal coming from the manufacturing PMI (which suggests some modest pickup in activity) over that coming from the ISM (which suggests a decline). Put another way, the gap between the two is more likely to close with the ISM recovering, than it is with the PMI falling back.

What does this mean for US manufacturing, and the economy more broadly? Manufacturing in the US has essentially flatlined over the past year or so, consistent with the broader global downturn in industry, which has been driven by normalising goods consumption in the US and weak demand in Europe and China. As described in our update on global manufacturing earlier this week, we see signs now of a bottoming out in industry, but we also see little reason to expect a very sharp rebound given the headwinds from continued tight monetary policy. Interest rates are expected to start gradually falling in the second half of the year, but inflation worries are likely to keep rates relatively high for at least the coming year or so. In that context, we see the pickup in the manufacturing PMI as consistent with the broader bottoming out – but no sharp rebound – story.

Manufacturing is less of a growth driver than in the past

Although the bottoming out in manufacturing is a modest tailwind, it does not mean very much for the US growth outlook. The US economy is a domestically-driven and largely consumption-led economy. Indeed, despite the weakness in manufacturing – which has stagnated over the past year – the economy has continued to grow robustly, driven by consumption. Manufacturing makes up just 10% of gross value added in the US, while the services sector has been on a near continuous path upwards and stands at over 70% of GVA. While it is true that the more volatile cyclical swings in manufacturing compared to services means that it can still impact growth, the falling share in GVA means that impact is waning. This is also reflected in the falling share of equipment investment in total private fixed investment, from 36% to 31% over the past ten years, whereas intellectual property investment has risen from 24% to 35% over the same period.