UK - Confidence crisis

Unease over the new government’s budget plans has driven a dramatic selloff in UK assets. The Bank of England will be forced to hike rates aggressively over the coming months – potentially to well beyond our new base case of 4%. This could lead to a catastrophic bust by 2024.

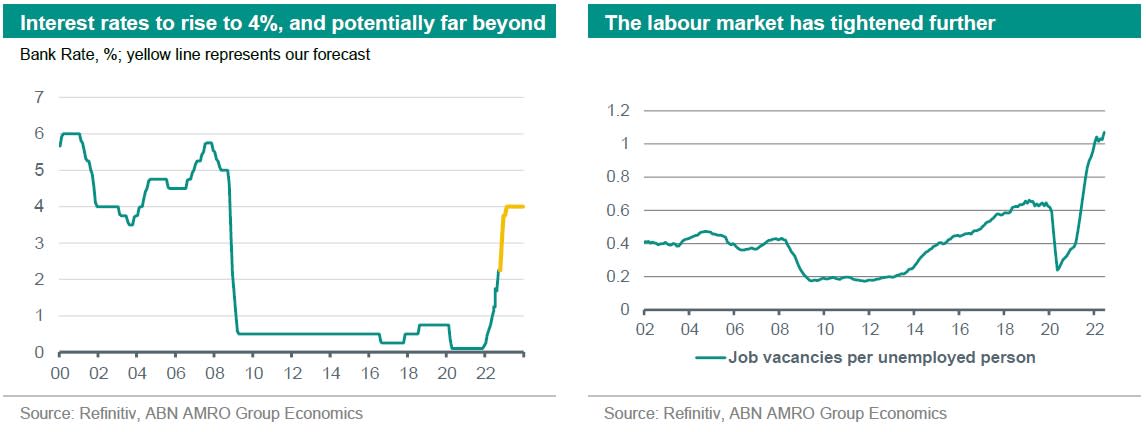

It has been a tumultuous month for the UK economy and financial markets. In particular, the market’s verdict was resoundingly negative on the new government’s plans to unleash a wall of debt-fuelled stimulus on a supply-constrained economy (see also here). Bond yields surged to new post-financial crisis highs, while money markets now expect the Bank of England to raise its policy rate to 5.5% by next summer. Ordinarily, the currency would strengthen on such a rise in interest rate expectations; instead, the value of sterling has plunged – against the dollar to a 37 year low. The plans to freeze annual energy bills for the average household at c.£2500 and support for business energy bills may help the economy avoid a deep recession in the very near term. But this delays the pain rather than avoids it. There is now a real risk that the Bank of England will be forced to raise rates much more aggressively than even our updated forecast of 4%, for two reasons. One is that the reduced hit to real incomes from the energy price cap, as well as the demand stimulus stemming from the biggest tax cuts since the 1970s, means that inflation is likely to stay above the 2% target well beyond 2023. The second reason is that the plunge in sterling is an even bigger near-term risk to the inflation outlook, given that the UK is a net importer of goods with a sizeable trade deficit. If the MPC does not follow through on current market expectations for 250bp in rate hikes at the coming two meetings, sterling could weaken further still, exacerbating the inflation outlook. Rate rises that go well beyond our 4% projection raises the risk of a catastrophic bust further down the line – with a deep recession by 2024.

Much will now depend on how policymakers react to the crisis in UK assets. The first line of defence has been the Bank of England, which issued a statement on Monday stating that the Bank ‘will not hesitate to change interest rates by as much as needed’. The BoE has since intervened in gilt markets, and we still would not rule out an emergency, inter-meeting rate hike to stabilise sterling. Ultimately, a U-turn on the policy measures announced by the government is the only fundamental fix to the problem. While politically this would represent an embarrassing climbdown, it might prove to be the least worst option for the government.

Economy has continued to weaken, but inflationary pressure has strengthened

Meanwhile, the economy has continued to weaken, with the mild contraction in output that began in Q2 likely to continue in Q3 – fulfilling the technical recession definition. This is partly due to the extra public holiday because of the Queen’s funeral in September, but activity indicators even before this have also suggested declines in output – retail sales have continued their downward trend, manufacturing has stagnated, and the PMIs have all fallen below the 50 mark separating expansion from contraction. Despite this, the labour market has remained remarkably tight, as despite a modest fall in job vacancies, the inactivity rate has continued to rise, leading to a net increase in overall tightness as measured by the job vacancy ratio. Wage growth also continued to pickup to 5.4% y/y, while core inflation accelerated further to a new 30 year high of 6.3%. Given all of this, and even in the absence of this month’s fiscal stimulus announcement, the Bank of England would in any case have been minded to continue tightening monetary policy aggressively.

This is part of the Global Monthly, see here.