Global Monthly - What if policymakers get the energy crisis wrong?

European markets, economies and governments are adapting rapidly to energy shortages. Gas consumption has fallen significantly, with rationing over the winter now likely to be avoided. However, there is now a risk that governments might go too far in their attempts to avert recession.

Full Global Monthly (including regional updates)

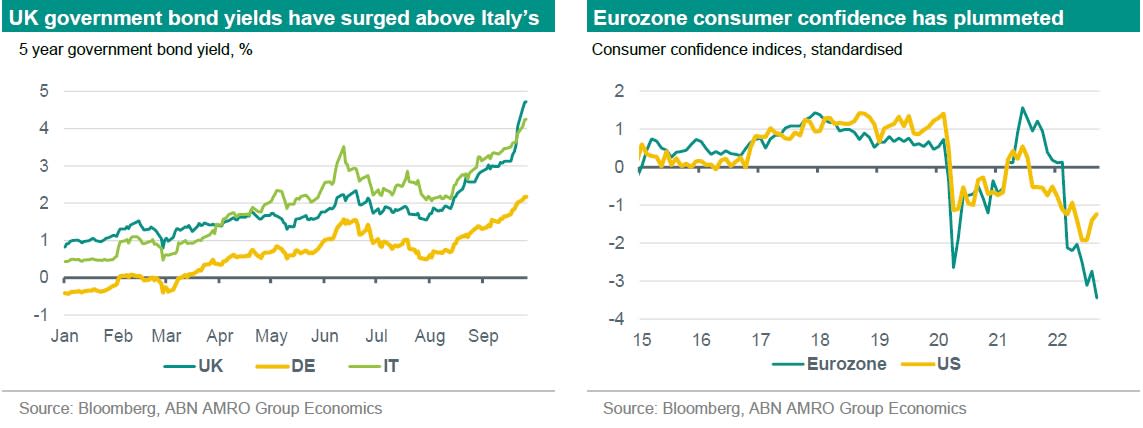

Global View: The UK’s confidence crisis highlights the risk of policymaking going awry

Since our last Global Monthly, the European energy crisis has entered a new phase, as markets, economies and governments have adapted to the new reality of energy shortages. The good news is that European gas inventories have continued to rise ahead of the heating season, prices have fallen significantly from the astronomical highs reached in August, and gas consumption among both households and businesses looks as though it is seeing a necessary and sustained fall. However, the risks remain significant, and increasingly, the policy response is coming under scrutiny as governments attempt to offset the pain of the energy crisis. The most spectacular example of this was the UK’s not-so-mini budget announcement last Friday, which contained a generous household and business energy price cap, and the biggest tax cuts since the 1970s – all entirely unfunded, and therefore implying a massive rise in the deficit next year. Ultimately, the central bank will be forced to offset most of the growth-supportive impact of these plans given the pressure the currency has come under, as well as the risks the policy poses to the medium-term inflation outlook. While aggressive fiscal policy moves on the scale of the UK’s are unlikely elsewhere in Europe, the market reaction served to highlight the risk governments run if they go too far with their interventions. Business and consumer confidence surveys over the past month suggest the eurozone and UK economies are probably already in a recession. While carefully calibrated policy measures might help to ease some of the pain of recession, they will not help economies escape the reality of supply constraints that they face.

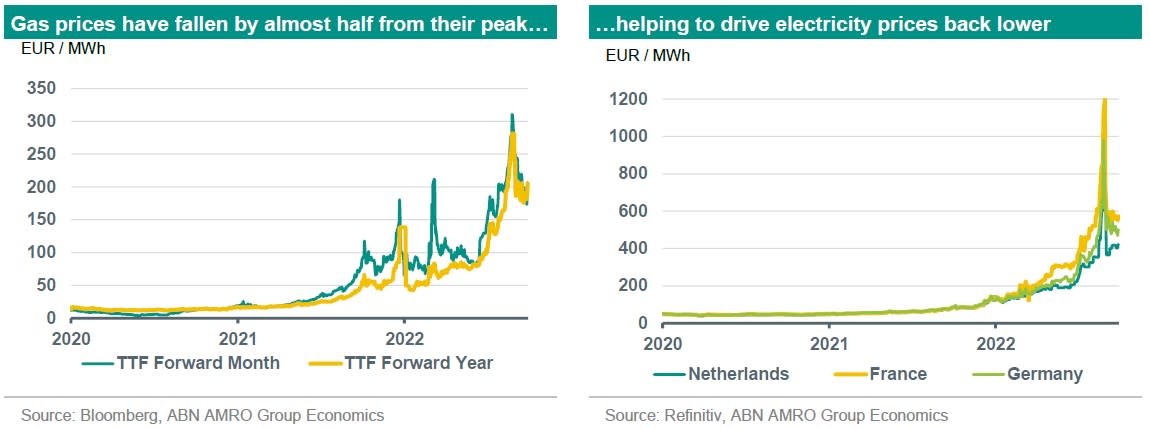

Energy prices have come off the astronomical highs set in August

Gas prices have fallen to almost half the peak level reached in August, as the signing of long-term LNG contracts, the opening of new floating regasification capacity at Eemshaven in the Netherlands, alongside the aforementioned ample inventories heading into winter led to a reduction in speculative long positioning in the gas market. Still, there remains significant uncertainty. While a mild or an average winter would mean Europe probably scrapes by without physical shortages, much depends on how demand evolves, and also how fierce competition from Asia will be for spot LNG cargoes. This will also depend on how severe the Asian winter is. In the event of a severe winter in either Europe or Asia, physical gas shortages could yet trigger another price surge back to the record highs we saw in August. The apparently deliberate sabotage of the Nord Stream pipeline – which triggered a rebound in gas prices in recent days – highlights also the risk of unforeseen events for prices.

Lower overall gas prices, as well as improved conditions for other power generation sources such as coal and nuclear, have also fed through to lower electricity prices. A number of French nuclear power plants are expected to come back online towards the end of the year, while a rise in Rhine river levels has made the transport of coal easier again in Germany. With that said, with progress stalling on EU attempts to de-link electricity prices from the gas price, for the time being electricity prices continue to be largely determined by gas market conditions.

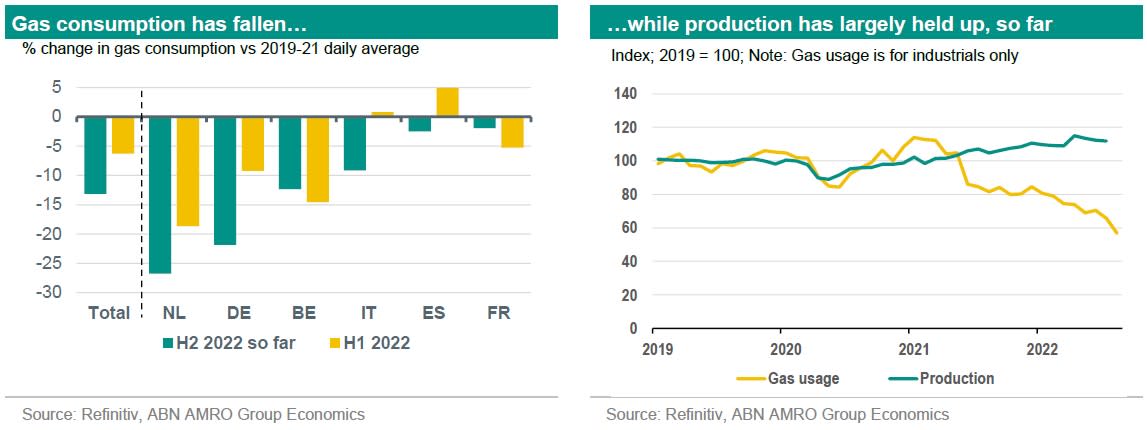

Falling gas consumption suggests physical shortages might be avoided

Further good news is apparent in the gas consumption data – something we are now tracking closely. Year-to-date, average daily gas consumption is now down by 8.5% across the ‘big six’ eurozone countries (the Germany, France, Italy, Spain, the Netherlands, Belgium). That fall has picked up pace particularly over the past few months as prices have surged further, with the daily average down 13.2% since July – approaching the EU target of a 15% cut in demand. At the same time, and as we have highlighted before for the Netherlands specifically, production has largely held up despite the declines in gas usage.

The drivers of the declines have varied. For households, homes are being better insulated and people are cutting back on cooling and heating in response to high prices. In industry, oil refineries for instance have made the relatively easy switch to using oil rather than gas as an energy source. In some other cases, producers have been able to idle capacity temporarily in the hope that prices would decline again at some point, relying on existing inventories of certain inputs in the meantime. In the cases where viable substitutes exist for gas, or where households or services providers are able to reduce consumption due to greater energy efficiency or acceptance of lower heating temperatures, the impact on output would remain minimal. However, for some producers the current consumption declines will be difficult to sustain without production cutbacks. This is one of the reasons we still expect the energy crisis to lead to declines in GDP over the coming quarters, and the weakness in a range of manufacturing indicators (notably the PMIs) recently is consistent with our expectation.

But government intervention runs the risk of clouding the incentives to lower gas use…

At the same time, the large declines in aggregate consumption hide significant variations between countries. In particular, the declines have been much larger in Germany and the Netherlands – where so far there has been relatively little intervention by governments to cap prices – than in France and Spain, where governments moved quickly to cap prices. As governments increasingly move in the direction of price caps, the data therefore highlight the danger that price caps might significantly reduce the incentive to cut back on energy use, which is ultimately necessary if Europe is to avoid a physical shortage of energy.

…as policy becomes increasingly supportive of demand

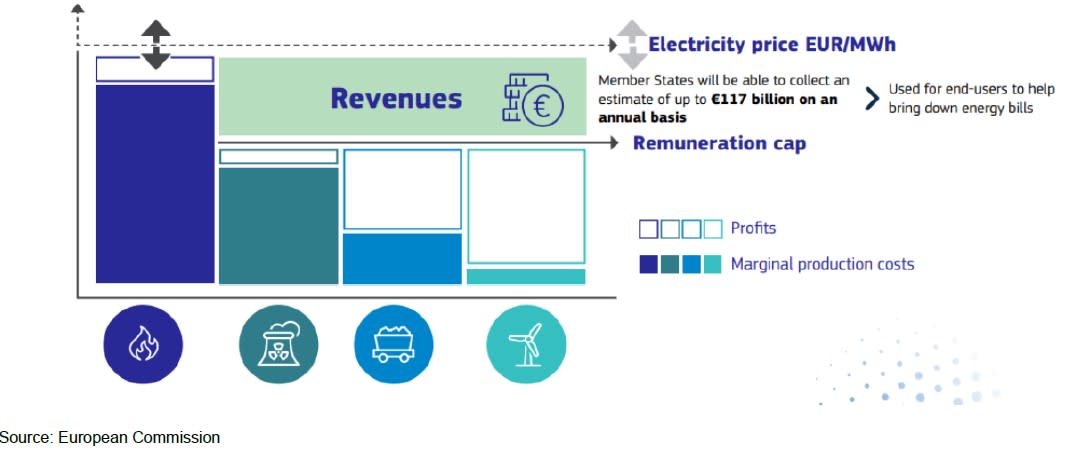

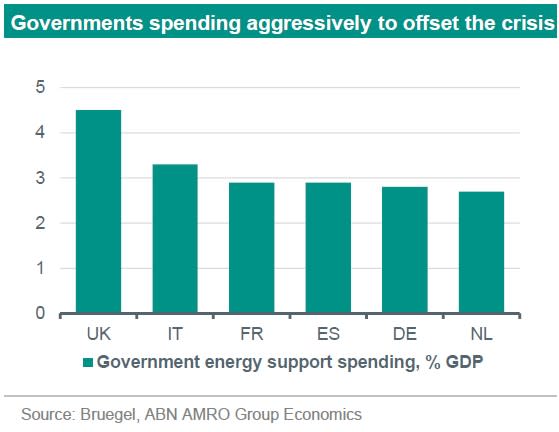

Indeed, the big story in recent weeks has been the increasingly muscular fiscal response to recession risks in Europe. Two major developments have been the announcements of household energy price caps by the Dutch and UK governments. In both cases, the caps are very generous and very expensive, but they differ in their impact on incentives to reduce energy use, as well as how they are funded. The latter is important not only from a debt sustainability standpoint, but also in terms of the net fiscal impulse to the economy and therefore its impact on the medium term inflation outlook. The cap in the Netherlands covers households and small businesses, but only up to a certain level of usage – above which market prices apply. In addition, although the cost of the plan is uncertain, a significant proportion is paid for by the rollback of an energy tax reduction that has applied until now, as well as a windfall tax on power suppliers that are not dependent on expensive natural gas (see figure below).

In the UK, in contrast, the cap applies regardless of usage, meaning that the incentive to reduce consumption is significantly blunted (there remains some incentive given that prices will still be much higher than before the crisis), while there is a separate cap in place for both SMEs and large corporate energy users (the Dutch cap only applies to SMEs). The other difference with the Netherlands is that other support measures will remain in place, and the government has ruled out imposing a windfall tax on non-gas electricity providers (an existing tax on the domestic oil and gas sector will remain). As such, the much higher cost of the UK plan, combined with the fact that it is entirely funded by debt means that it is a significantly bigger net fiscal impulse to demand in the economy.

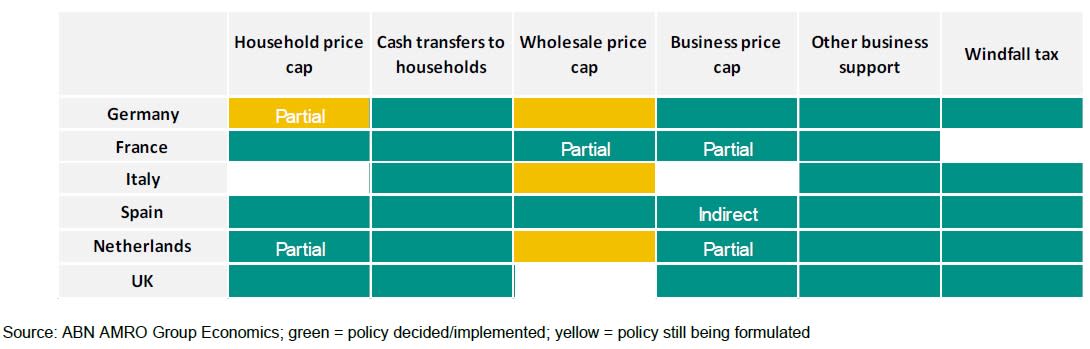

These policy announcements are just the latest in a raft of interventions by European governments over the past year, which we summarise by country in the table below.

Policies have ranged from direct cash transfers to the most vulnerable households, to sweeping price regulation mechanisms. And there is still more to come: Germany is currently working on its own household energy price cap which, like that of the Netherlands looks likely to come with a usage limit, and will be partly funded by an energy windfall tax. At the EU level, meanwhile, work continues on the development of a wholesale gas cap, and a cap on electricity not generated by gas. In Italy, while the government has already made significant interventions over the past year, its newly-elected government could also come with additional measures over the coming months.

Three risks from doing too much

While it is understandable that policymakers are acting to shield households and businesses from the worst effects of the energy crisis, we highlight three reasons for caution. First, there is the danger that price caps reduce the incentive to lower consumption, which is necessary given the very real risk Europe faces of energy shortages during the winter months. In that regard, price caps that apply up to a certain threshold of energy use – as we see in the Netherlands – look better placed to achieve that goal. Second, in an environment of significantly constrained supply and high inflation, providing blanket stimulus to the economy is like adding fuel to a fire. As such, any gain from growth will be short-lived and counter-productive, because central banks will have to act more forcefully to counter the effects – as we are now likely to see in the UK (and with deeply damaging implications for the economy). It is notable, in this respect, that ECB President Lagarde warned against generalised fiscal stimulus in her remarks this week to the European Parliament. Thirdly, with interest rates surging, governments no longer have the same room to rapidly expand deficits without triggering negative reactions from the investors that are being asked to finance those deficits, as again the example of the UK has shown over the past week. This raises risks to financial stability that in turn can further weaken the growth outlook.

In short, governments face a very different environment to the one they faced in the early stages of the pandemic, when inflation and interest rates were at historic lows, and there was little prospect of a shortage of anything in the economy. Responding in the same way as during the pandemic could therefore backfire.

A recession in Europe still looks unavoidable

Given the above constraints, we continue to expect a recession in European economies over the coming year. Europe looks likely to get through the coming winter without physical shortages of energy, but this will still come at a cost – both in the form of falls in people’s real incomes, and losses in production as manufacturing capacity is idled. In cases where governments do attempt to fully ease the pain with fiscal measures, this is likely ultimately to be offset by steeper rises in interest rates by central banks – as well as raising the risk once again that energy shortages become realised.