The strategic approach to critical raw materials

The EU recently published its Critical Raw Materials Act. The EU set targets for domestic capacity and aims to limit the supply from a single country by 2030. It also updated its list of critical raw materials and released a list of strategic raw materials. The US and the UK had have already published their strategies. The EU approach is similar to that of the US.

The strategic approaches of the big developed economies to critical raw materials are now all out in the open, with the EU being the latest to publish its plans

The EU sets targets for domestic capacity and plans to limit the supply from a single country by 2030

The EU updated its list of critical raw materials and released a list of strategic raw materials

The US and the UK had already done so

The approach of the US and EU is similar, but the UK seems less hands on

Introduction

The race is on to decarbonize the world by 2050. There are certain technologies that are crucial to help to this endeavour. However, these technologies depend on a number of raw materials that are experiencing rapid demand growth and high concentration of supply chains in particular countries. Some of these materials are produced in comparatively small volumes or as by-products of other mining activities. In a large number of these minerals, China dominates the extraction, the processing or both. As countries increasingly understand their dependence on the supply of these materials they have come up with strategies to help secure their future supply. In this report we focus on what are critical raw materials and what actions EU, the US and the UK have taken to secure supply.

EU strategy to critical raw materials

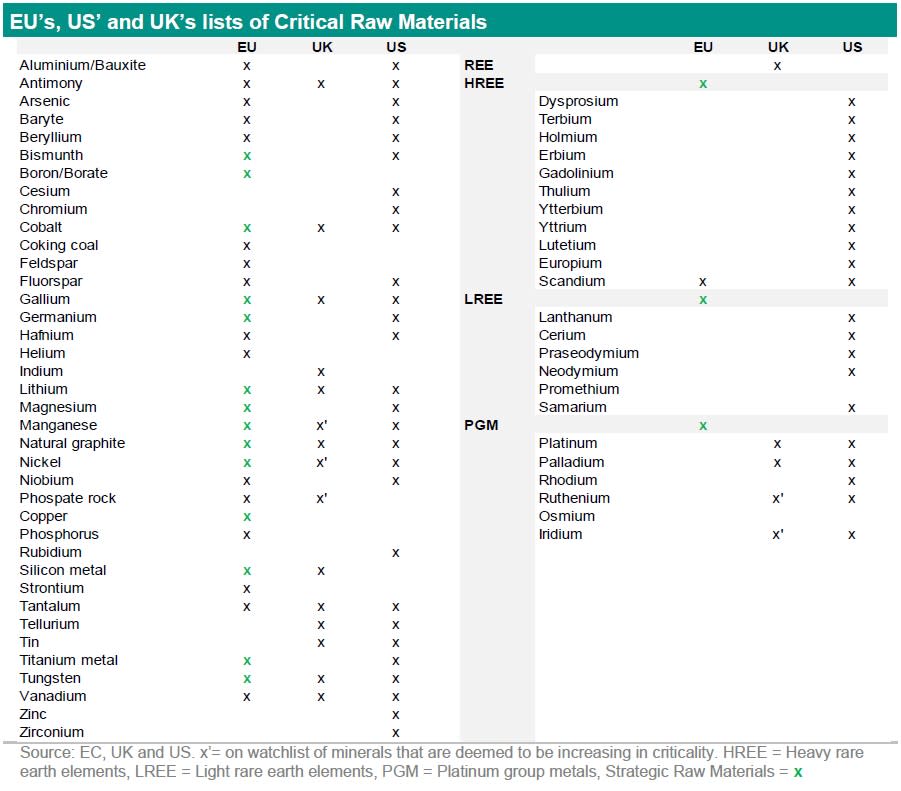

On 16 March 2023 the EU released the Critical Raw Materials Act (see ). The Commission proposed a set of actions to ensure the EU’s access to a secure, diversified, affordable and sustainable supply of critical raw materials. The EU uses a criticality methodology based on two main criteria: Economic Importance (EI) and Supply Risk (SR). The EU has defined 34 raw materials as critical raw materials (see table below). Within this list, some critical metals are defined as strategic materials as they are seen as crucial to technologies important to Europe’s green and digital ambitions and for defence and space applications. Lithium and titanium metals are examples of these. Lithium is used for batteries in electric vehicles and for storage. Titanium metal is used in aerospace and defence. In the list of 34 materials are three material groups such as Platinum Group Metals (PGM), Heavy Rare Earth Elements (HREE) and Light Rare Earth Elements (LREE). The full list of critical raw materials as defined by the EU is in the table at the end of this report (see ).

The EU sets clear targets for domestic capacity along the strategic raw material supply chain and to diversify EU supply by 2030. These targets are set as percentage of the annual consumption that is needed by 2030:

10% of annual consumption of the minerals needs to be extracted from Europe

40% of the annual consumption of processed materials needs to come from within Europe by 2030

15% of annual consumption need to come from recycling by 2030.

In addition not more than 65% of the EU’s annual consumption of each strategic raw material at any relevant stage of processing can come from a single country. Currently China is the major supplier of 21 critical raw materials of the EU including strategic raw materials.

The EU will take the following steps to meet these targets. For a start, the EU will reduce the administrative burden and simplify permitting procedures for critical raw materials projects in the EU. Indeed, Selected Strategic Projects will benefit from support for access to finance and shorter permitting timeframes (24 months for extraction permits and 12 months for processing and recycling permits). In addition, Member States will also have to develop national programmes for exploring geological resources. Moreover, the Critical Metals Act provides for the monitoring of critical raw materials supply chains, and the coordination of strategic raw materials stocks among Member States. Furthermore, Member States will need to adopt and implement national measures to improve the collection of critical raw materials rich waste and ensure its recycling into secondary critical raw materials. Products containing permanent magnets will need to meet circularity requirements and provide information on the recyclability and recycled content. Finally, the EU will need to strengthen its global engagement with reliable partners to develop and diversify investment and promote stability in international trade and strengthen legal certainty for investors. In particular, the EU will seek mutually beneficial partnerships with emerging markets and developing economies, notably in the framework of its Global Gateway strategy. The EU will invest in research, innovation and skills.

The proposed Regulation will be discussed and agreed by the European Parliament and the Council of the European Union before its adoption and entry into force.

US inflation Reduction Act

The US had already taken actions to try to secure the supply of critical materials. On 16 August 2022 the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) was signed into law. The Inflation Reduction Act’s $370 billion in investments will lower energy costs for families and small businesses, accelerate private investment in clean energy solutions in every sector of the economy and every corner of the country, strengthen supply chains for everything from critical minerals to efficient electric appliances, and create good-paying jobs and new economic opportunities for workers. Built within the IRA is a commitment to increasing the domestic US supply of critical minerals to provide the materials necessary for a vast expansion in (EVs), batteries, and renewable power production infrastructure. Under the advanced manufacturing production credit outlined in the legislation, mining companies that produce any of the critical minerals listed in the bill will qualify for a tax credit equivalent to 10% of the cost of production for that mineral. The minerals produced must meet specific purity levels to qualify for the credit. To satisfy the IRA's critical minerals requirement, at least 40% the value of the critical minerals contained in the vehicle's battery must be "extracted or processed in any country with which the United States has a free trade agreement in effect" or be "recycled in North America." The required percentage would increase gradually to 80 percent by 2027. Vehicles that satisfy this requirement would receive a tax credit of $3,750, provided that they otherwise qualify as a "clean vehicle" as defined in the IRA. A similar rule in the IRA would provide an additional tax credit of $3,750 if at least 50 percent of the battery's components are manufactured or assembled in North America (increasing to 100% by 2029). An overview of the critical metals defined by the IRA is the table on the next page.

UK’s Critical Metals Strategy

The UK has also come up with a strategy to secure the supply of critical metals. On 13 March 2023 the UK government released its policy paper: Resilience for the future: The UK’s Critical Minerals Strategy (see ). The UK government takes a similar approach to those of the US and the EU. It has defined a list of critical metals. It defines critical metals as minerals with high economic vulnerability and high global supply risk. These ‘critical minerals’ are not only vitally important but are also experiencing major risks to their security of supply. The strategy is to accelerate growth of the UK’s domestic capabilities, collaborate with international partners and to enhance international markets to make them more responsive, transparent and responsible. The UK has not yet set targets as the EU and the US have done.

Lists of critical raw materials

Critical raw materials are materials where the extraction and or processing is often concentrated in area/country, they are difficult to mine, and in high demand for the products used and for the technologies that are crucial to reduce CO2 emissions. The EU, the UK and the US have defined separate lists of critical raw materials. The EU even has a separate list of strategic raw materials. These are the crosses in green in the table on the next page.

These lists have a lot of similarities but there are also differences. To start with the similarities. The US, EU and the UK define often the same materials as critical. Moreover, they may be more specific on the rare earth elements but they are for all three countries classified as critical. There are also a number of differences. As mentioned earlier rare earth elements are mentioned in different detail. The US has provided the most detail. The US named the individual rare earth elements, while the EU splits them into heavy and light rare earth elements and the UK grouped them into one group rare earth elements. Another difference is that some materials are deemed critical for one of the countries but not for the other countries. This difference could be the result of domestic extracting and processing capacity but also less demand for a certain technology where a specific materials are used. For example for the UK Indium is a critical metal that is used in touch screens, flatscreen TVs and solar panels, while the mineral is not on the list of the EU and the US. In case of the EU, Indium was removed from the list because the EU’s domestic production largely covers the EU needs. Another example is that the US has Cesium on its list that is used as drilling fluid and to make optical glass while the EU and the UK don’t have it on their lists. As a disclaimer the EU did mention all raw materials, even if not classed as critical, are important for the European economy and that a given raw material and its availability to the European economy should therefore not be neglected just because it is not classed as critical.

Conclusion

The strategic game of securing the supply for critical raw materials was already underway but has become more clear and determined. China has been far advanced in this and the US, UK and EU are trying to catch up to secure the supply of these materials and support their economies and industries. These materials are also crucial in the technologies to decarbonise the world by 2050. Higher domestic supply and higher recycling will decrease the dependency but some materials can simply only be found in some places in the Earth’s Crust. The question is if reserves in these materials will ever be enough to decarbonize the world. We don’t think so at current technologies. So it is a race to secure the reserves and to position well strategically as long as there are no significant breakthroughs in technologies that result in substantially lower demand for these materials. Some technologies could even result in no demand for a material that is currently deemed as critical or of strategic importance. An example is cobalt. If battery technology advances and new batteries don’t require cobalt anymore then demand for this now critical metals will almost disappear.