SustainaWeekly - Scoring the impact of climate risks on sectors

In this edition of the SustainaWeekly, we first provide a summary score of the impact that physical and transition risks will have on 20 sectors of the Dutch economy as well as taking a closer look at the impact of mitigation policies by the government. We then go on to assess the recently disclosed ECB data on climate-related indicators at the euro area level. These indicators will help policy makers to assess climate risks, and to better understand challenges and opportunities around the climate transition. Finally, we analyse the transition for commercial vehicles. For the sector to meet emission reduction targets there are three main challenges: the range and freight challenge, the refuelling infrastructure challenge and the charging infrastructure challenge.

Economist: Climate change and policies to mitigate it will impact 1) business revenue and costs 2) the value of assets and liabilities and 3) the availability and cost of capital. We score the impact that different physical and transition risks will have on 20 business sectors as well as the potential impact of price and non-price based policy measures.

Strategist: The ECB has recently disclosed data on climate-related indicators. From a first glance, we see that investment funds seem to have the largest financed emissions and also the largest weighted average carbon intensity, but banks have the largest carbon footprint. The data also still has several limitations and must therefore be treated with care.

Sector: Commercial vehicles account for almost half of the emissions of the mobility sector so will be a key part of the transition. For commercial vehicles to meet emission reduction targets there are three main challenges: the range and freight challenge, refuelling infrastructure challenge and the charging infrastructure challenge.

ESG in figures: In a regular section of our weekly, we present a chart book on some of the key indicators for ESG financing and the energy transition.

Impact of climate risks spans across multiple sectors

Climate change and policies to mitigate it will impact 1) business revenue and costs 2) the value of assets and liabilities and 3) the availability and cost of capital

We score the impact that different physical and transition risks will have on 20 business sectors in Netherlands

Governments are using a variety of price and non-price based policy measures to facilitate the transition

Overall, in our view, having an up-to-date understanding of all technological developments in the sector (national and international) and in policy and regulations will become more crucial

Climate change and the policies to mitigate it have a major impact on virtually all sectors of the Dutch economy. It is no surprise that decarbonisation is gaining importance in many companies, both to reduce emissions as well as to manage policy-related risks to their businesses. It helps to have insight into the extent to which climate risks affect the business activities of companies in sectors. It is good for strategic decision-making and it increases ultimately financial resilience. In this note we provide a summary score of the impact that physical and transition risks will have on 20 sectors of the Dutch economy. Next to that, we take a closer look at transition shocks and in particular, we focus on mitigation policies by the government.

Impact of climate risks

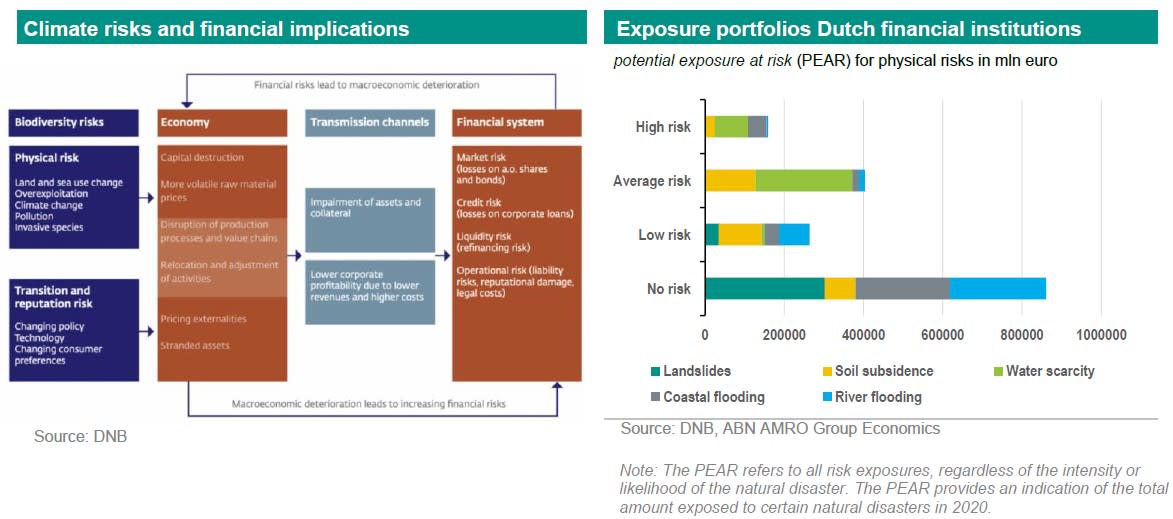

Climate-related risks are uncertain and nonlinear. They are divided into two types: physical and transition climate risks. Physical risks involve acute events (such as floods, heat waves and drought) and chronic events (such as sea level rise, higher temperature and increased rainfall). Despite the fact that some of these risks are predictable to some extent (particularly with the chronic risks), there will be continuous uncertainty with each risk type about location, frequency and ultimate severity of those events. For transition risks, that uncertainty is fuelled in particular by changes in government policies, technological developments, shifts in consumer preferences and confidence.

For businesses, these risks have implications for revenues and costs, as well as for the value of assets and liabilities, and/or the availability and cost of capital. Floods, heat waves and droughts cause damage to real estate and infrastructure. In addition, they disrupt supply chains in many sectors. Mitigation policies – such as carbon prices – can make certain activities uneconomical. On the other hand, climate risks also bring opportunities to sectors. For example, it causes companies to try to mitigate the effects of climate change or to adapt to the new reality. This can be done by using resources more efficiently, by cost savings, by using low-emission energy sources, building more flexibility in the supply chain, by developing new products and services, but also, for example, adopting and developing innovative decarbonization techniques.

Supervisors of financial institutions have attached great importance to assessing the climate risks in their portfolios. And the good news is that financial institutions can proactively reflect the financial consequences of climate risks in both the short and long term with increasing accuracy. Thus, the challenges posed by climate risks are becoming better understood, especially what the impact is on different sectors. For regulators, this information is crucial. On the basis of this information, they can assess the risks in a more adequate way, better ensure the resilience of the financial system and adjust their policies accordingly if and when required.

Incidentally, the sector approach is traditionally used. This approach is a good starting point and provides a solid foundation, especially for transition risks. This is because the impact of government policies, technological advances and shifts in consumer preferences have effects primarily at the sector level. Every company in every sector faces these transition risks in one way or another sooner or later. However, the high variability of the ultimate impact of the climate risks can differ significantly between companies within sectors.

Government climate-related policies aim to mitigate climate change by accelerating the transition of the economy towards net zero emissions. This can be done, for example, by making the emissions trading system more stringent, by introducing or by raising the carbon tax, by adjusting subsidies to encourage low-carbon measures or discourage use of fossil fuel. As technological developments accelerate, companies' existing plant and machinery may become obsolete faster or the use of energy sources may become more expensive due to, for example, stricter efficiency standards. To remain competitive, companies must therefore adapt. Finally, consumer and investor climate sentiment also affects business activities. For example, an increase in the need for climate-friendly variants could result in a shift to more climate-friendly transportation, production and energy use.

For physical climate risks, the emphasis is somewhat different. These risks primarily involve the location of business operations as well as of suppliers. It manifests itself primarily in damage and disruption to production facilities, datacentres, warehouses and other business facilities of companies, as well as through their supply chains. Nevertheless, even here a meaningful assessment of the overall risk can be made at the sector level. Sufficient information is available on the distribution of companies across the Netherlands, for example, and flood risks – which are particularly important for the Netherlands - by area are well mapped. Using the combination of this information, a reasonable estimate can be made of the impact at the sector level.

Ultimately, both physical and transition risks inflict economic damage on businesses in sectors. The physical risks mainly damage buildings, establishments, infrastructure. They also affects productivity and labour availability. But they can also involve write-downs of bonds and shares of companies whose properties or processes are exposed to the physical effects of climate change. Transition risk usually also involves write-downs of investments in and loans to businesses or write-downs in real estate holdings. Incidentally, higher transition risk also means that companies have to build higher financial buffers for their assets. On balance, climate risks affect an organization's future financial position, the impact of which on assets, sales, costs and thus profits are very important to monitor. In any case, it is clear that climate change affects all economic sectors in one way or another, but there are differences by sector

The physical impacts of climate-related shocks and the transition to a low-carbon economy not only affect the financial situation of companies, they also shape the strategic decisions companies make. These strategic decisions should increase the financial resilience of companies as much as possible. To make informed decisions about future operations in relation to climate risks, we have mapped the net impact of these climate risks by sector.

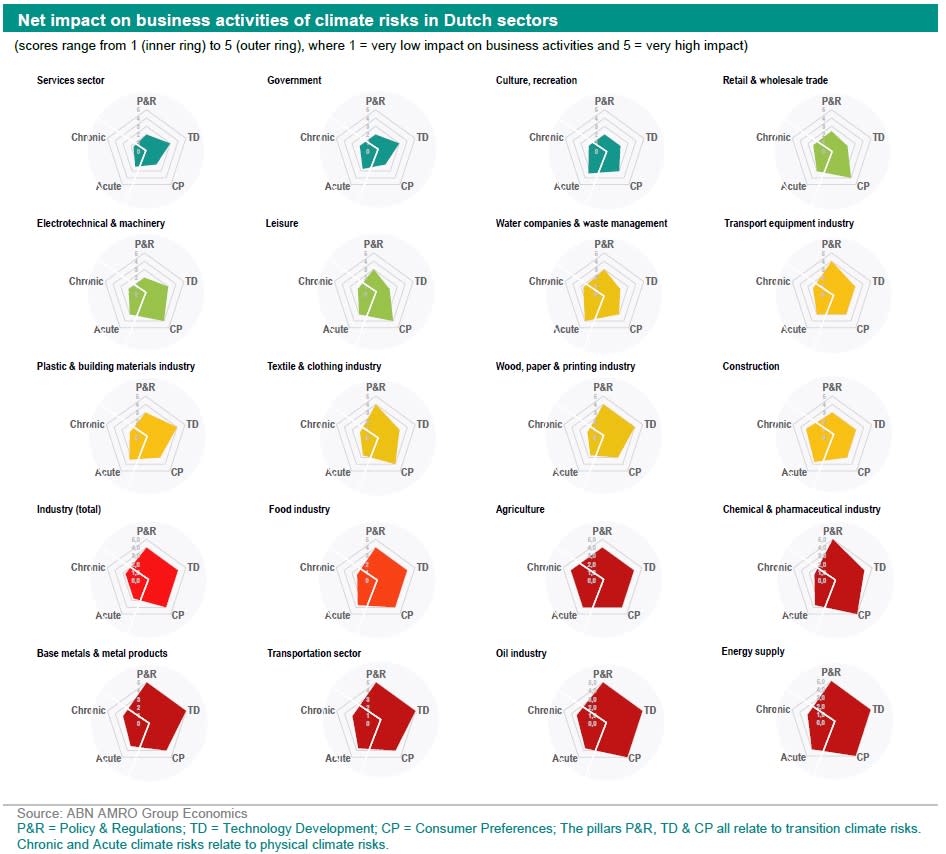

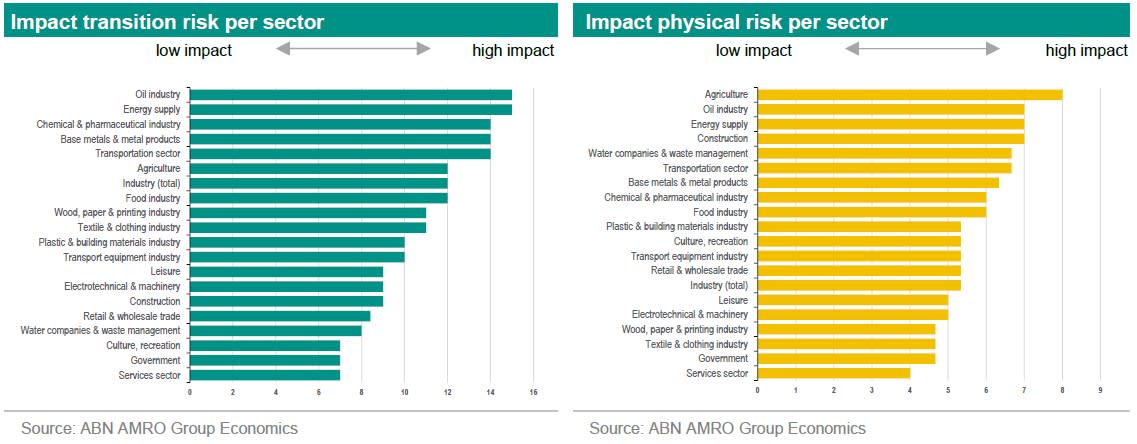

We plot the impact of physical and transition risks by sector on five pillars, where two pillars ("chronic" and "acute") relate to physical risks. The three remaining pillars relate to transition risks, namely the impact of changes in government policy ('P&R'), technological developments ('TD') and shifts in consumer preferences and confidence ('CP'). The government has a number of price and non-price based tools to hand. An overview of the results is presented in the circle figures for 20 sectors. The smaller the coloured area in these figures, the lower the impact on activities in the sectors will ultimately be. The colours run from dark green (very low impact) to dark red (very high impact).

For the assessment of the acute physical risk impact, we were able to form a reasonable assessment based on existing data (mainly the distribution of companies across regions and the probability of flood risk in those regions). There are no exact data and data available per sector for shocks such as 'drought', 'heat waves' and 'extreme weather' (such as storms). Chronic physical risks have a lower score than acute physical risks in most sectors. The most important input for making the scores with regard to 'Policy & Regulations' (under transition risk) is the sector's dependence on the use of fossil fuels. For the other two pillars under transition risk (‘technology development’ and ‘consumer preferences’), the scores are partly based on our own research, including, for example, the publication ‘Decarbonisation strategies in Dutch sectors’ (see here). Over time, more data will become available with which we can further improve our analysis of climate risks and the impact on sectors. Therefore, these first results that we present in this article are subject to change.

Immediately it can be seen from the overview with the preliminary results that seven sectors (excluding the "Industry (total)" sector) have a high to very high impact and six have a low to very low impact. Six sectors face an average impact of climate risks.

No sector escapes the physical effects of climate-related events. Here, acute shocks tend to have the greatest impact. Such shocks almost directly affect business activity in sectors more closely linked to weather events. Broadly speaking, these include sectors such as agriculture, construction, water utilities, healthcare, transportation and those heavily dependent on tourism. But the impact is also relatively high on sectors such as energy supply and the petroleum industry. For example, physical shocks directly affect the electricity system: from generation potential to transmission and distribution networks. And in the petroleum industry, it will mainly affect infrastructure (e.g. pipelines) or damage to terminals (which are often close to the coast). In the case of transition risks, those sectors that are more heavily dependent on the use of fossil fuels in the production process are particularly hard hit. This particularly involves many subsectors of industry, but also includes energy supply and the transport sector.

As we noted earlier, no sector will be spared in climate-related shocks. An acute or chronic climate shock also affects many employees of companies personally and thus directly ensures that the productivity of many companies is also affected. Yet there are some sectors whose resilience to climate risks is relatively better. These are mainly commercial and non-commercial (government) services.

Unpacking transition risks

In the analysis so far we have considered three types of transition risks - consumer preferences, technological developments and government policies and regulations. In this section we take a closer look at transition shocks and in particular, we focus on mitigation policies by the government.

We focus on government policy for three reasons. First, transition shocks driven by policy are expected to have a larger impact on the business operations in almost all the sectors that we have considered in this analysis (see chart above) compared with physical and other transition risks. Second, government policy is an immediate risk. The net zero ambition is fully embedded in the policy agenda in the EU and that comes alongside stringent interim emission reduction targets for 2030. By contrast, the physical effects of climate change are expected to emerge meaningfully over a longer period.

Governments have implemented and announced a wide variety of price and non-price measures to achieve the interim target and net zero. Of these, price-based measures such as carbon taxes have taken centre stage in policy analysis because the additional cost imposed on emissions from the tax fits neatly into a narrative that frames emissions as a negative externality that needs to be appropriately priced. Economic theory, in fact, suggests that a carbon price is the most efficient tool when the market fails to price GHG emissions. A price on emissions is efficient because the government does not need to know the technology options available to industry or for that matter consumer preferences. A carbon price allows the market to identify the least costly path for reducing GHG emissions and there is the added benefit that the revenue from the tax can be used by governments to lower debt levels, compensate less well-off households or to eliminate distortionary taxes such as labour taxes. That is the theory.

The reality is that carbon taxes are politically difficult to implement because the tax is visible and the burden tends to fall disproportionately on the less well off. As a result, governments rely heavily on non-price abatement measures such as regulations and planning. Also, carbon taxes are not always appropriate. They work best in sectors where substitution of product/technology is possible.

A good example of multiple abatement measures is the energy supply sector which includes power generation and distribution sectors. Governments have used price-based measures such as developing carbon emission trading markets (ETS) and introducing carbon taxes and feed-in tariffs, but also non-price measures such as regulation that, for example, compels a substitution to wind or solar power, as well as planning. Renewable energy requires a wide distribution network that links existing networks across municipal and national boundaries. Establishing these links requires agreements, planning and investment by government. Another example is town planning that aims to reduce private car usage by providing affordable and convenient public transport. All these are examples of policy intervention where the market on its own fails to internalise the costs of emissions. Indeed, the theoretical justification for non-price measures is the existence of multiple market failures in the economy.

The note later in this publication on commercial vehicles outlines the different price measures and regulations imposed on the sector by the EU and the Dutch government to facilitate the transition. The mobility sector, which includes commercial and non-commercial vehicles, is required to reduce emissions by a-third by 2030 compared with 2020 levels. The sector is a good example of multiple market failures that include technological challenges as well as infrastructure bottlenecks. Government policy aims to address these failures by encouraging new demand for EVs and hydrogen-powered vehicles with price measures and regulation and at the same time addressing the infrastructure bottlenecks with regulation and planning. The table below highlights some of the policy initiatives that are specific to this sector.

Conclusion

All-in-all, physical and transition risks have many impacts on operations, with transition risks typically having a higher impact than physical risks. Governments will deploy a plethora of price and non-price measures and the impact of these and other transition and physical shocks can vary significantly. Companies would do well to identify the potential impact of these risks. Differences by industry and company can be significant. Some organizations are much more resilient to change due to climate-related risks than others. Moreover, from an investment perspective, it is important for companies to have an indication of the potential climate-related impacts on their assets, especially those with long lives and clear policy guidance helps the planning process. Having an up-to-date understanding of all technological developments in the sector (national and international) and regulation will become more crucial.