Russia-Ukraine macro-economic implications

Yesterday, Russia launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine from multiple fronts, taking the conflict from one isolated to the eastern breakaway regions to one seemingly with the goal of regime change. The US and European governments have levied additional severe sanctions on Russia on top of those announced on Tuesday. In this note, we sketch out the broad implications of the Russia-Ukraine conflict, and of the resulting risk to commodity supply chains. We will communicate further on the macro-economic and market implications in the coming days.

Additional sanctions announced yesterday involved the freezing of Russian assets and transactions and further curbs on Russian banks. However, sanctions stopped short of more extreme measures such as a ban on Russia’s use of the SWIFT payments system. The latter would make it extremely difficult (if not impossible) for Russia to continue selling key commodities to European trade partners, and so while the chance of this move has increased, it remains a low probability.

The crisis immediately plunged financial markets into risk-off mode, with equity markets in freefall, safe havens such as Bunds outperforming, and commodity prices – particularly energy – spiking. While the implications of the conflict and the reactions are many and multi-faceted, in this note, we outline our thoughts on the main macro-economic implications. We continue to think the main channel of impact is via energy, and that Europe will be much more impacted than the US. We focus on two key scenarios – one where commodity prices continue spiking higher, and another, more severe scenario where price spikes are accompanied by physical disruption to gas supplies to Europe. We also offer an additional third, very negative scenario involving broader commodity supply disruptions including to oil, to which we attach a low probability (<5%). These scenarios roughly follow those we outlined previously in , with adjusted probabilities.

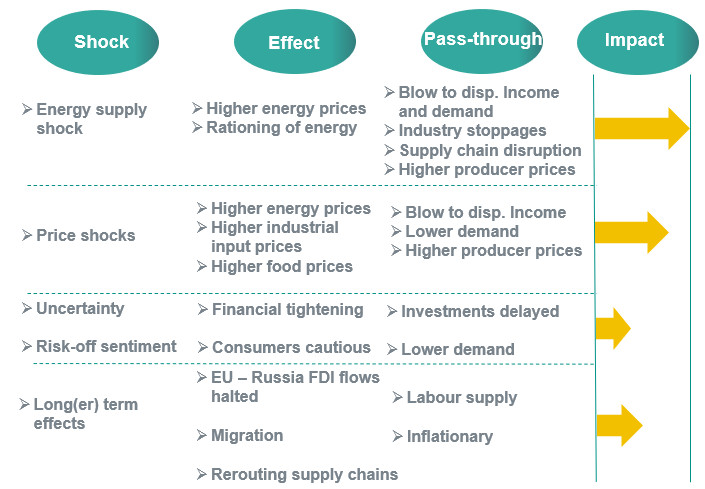

In the below infographic, we lay out the main channels of impact from higher commodity prices and of potential disruptions to supply.

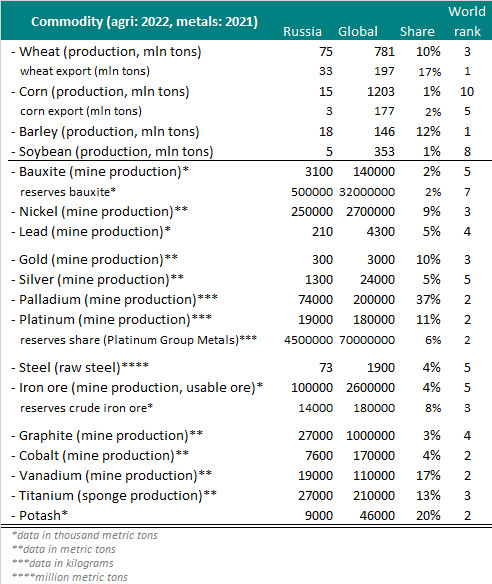

Russia is a commodities powerhouse

A key consideration for our scenario analysis is the significant share Russia has in major global commodity supplies – not just in oil and gas, but also wheat (it is the number 1 world exporter), and in key metals such as palladium (used for car catalytic converters) and nickel (batteries). See below for a summary.

Note that the economic impact of potential export restrictions on more fungible metals and agri commodities is not as severe as it is for gas, which is heavily dependent on physical infrastructure (pipelines and LNG terminals) needed to source supply from elsewhere. For instance, China has now approved the import of wheat from Russia, a commodity it currently buys from the US. US wheat supply could be diverted to other regions in this scenario.

Three scenarios: 1) Price shock, 2) Supply shock 3) Severe supply shock

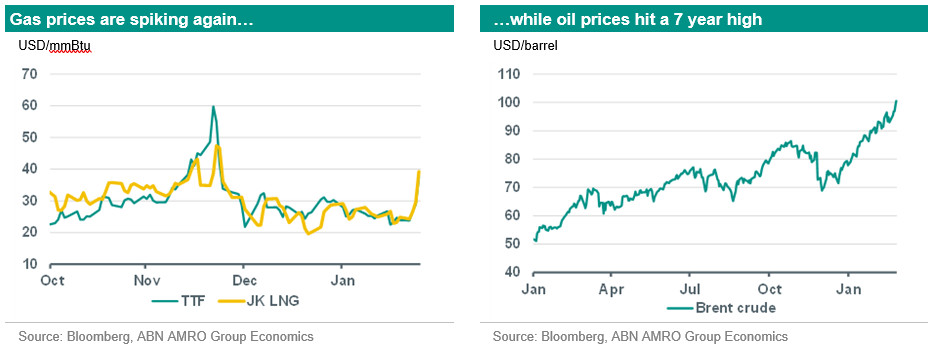

The price shock scenario (probability: 75%) - In this scenario (which is now unfolding), commodity prices continue their surge higher, and prices remain elevated for the foreseeable future, until we see some moves to de-escalate the conflict. Already, European 1 month ahead gas prices have jumped by more than 50% to the highest level since mid-December, and oil prices rising by much smaller magnitudes of c.6-7% (European benchmark Brent crude in particular jumped above $100 per barrel). Similar price spikes are visible in other key commodities where Russia and/or Ukraine are major suppliers, such as wheat and palladium. Prices are likely to continue spiking in the near-term as markets continue to digest the increased risk of disruption to commodity supplies.

Price spikes will have macro-economic implications – primarily by pushing inflation higher, but with second round effects likely dampening economic activity. Europe (the eurozone and UK) is still expected to be the hardest hit in this scenario, particularly via the gas price channel, as it is heavily dependent on Russian supply (the US, in contrast, is relatively insulated). However, we think it is likely that fiscal authorities will make further interventions to soften the blow both to households and industry, and to minimise economic disruption. With regards monetary policy, while elevated inflation limits the scope for a significant easing of policy, the downside risks to growth makes the risk even greater that the ECB will abort its planned end of asset purchases and rate hikes that we currently have in our base case for December.

Given the fluidity of the situation, we judge that it is too soon to make concrete forecast revisions, but will provide updates in due course.

The supply shock scenario (probability: 20%) - In addition to the price shock, physical supplies of gas are disrupted, perhaps as a counter-response to western sanctions. This depends naturally on just how severe western sanctions become. As well as even bigger gas price spikes, electricity markets would also see significant price surges as a spillover effect. European economies would need to ration energy supplies in order to ensure household energy security, and this would likely lead to industry stoppages where energy intensity is high. As well as pushing inflation higher still, this would cause contractions in economic activity – i.e. we would essentially be facing a stagflation scenario.

What could central banks do? With the need for government support likely to be even greater in this scenario, the risk of yield spreads between core and periphery debt widening would increase significantly. This would likely lead to the ECB stepping up asset purchases to stem spread widening. For the Fed, however, given that: 1) the US economy would be much more insulated from the effects, as it is energy independent, and 2) its inflation problem is much bigger than that of Europe’s, we think the bar for the Fed to delay a tightening of policy would be much higher. If anything, it could mean a slower pace of rate hikes, but policy tightening would likely still take place.

The severe supply shock scenario (probability: <5%) - In this scenario, western governments impose a ban on Russia’s use of the SWIFT payments system, causing major disruptions to all Russian commodity exports (i.e. not just gas, but also oil, metals and food). Alternatively, Russia itself imposes an export ban against Europe/the US. Either scenario would probably result in a global bottlenecks crisis. This would lead to even bigger shortages and price surges. For the global economy, we would expect the effects on growth (downward) and inflation (upward) to be intensified, with the US likely to be much more affected, as jumps in gasoline prices and even higher inflation broadly would weigh heavily on consumer confidence. The need for increased shipping capacity as European oil imports are redirected from Russia to other regions would put additional pressure on already strained global shipping infrastructure. This would add to the many bottlenecks currently weighing on global industry, and intensify inflationary pressures more broadly.

Will Beijing help Moscow?

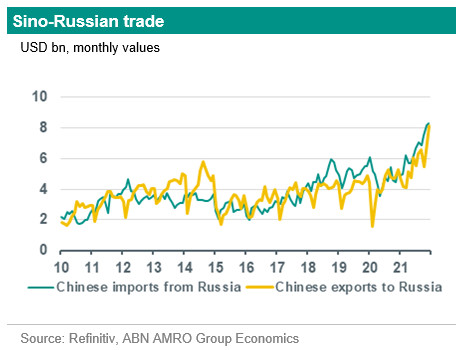

One of the questions related to the impact of tougher sanctions on Russia is to what extent China may help mitigating their impact. This issue is not new: China also supported Russia after the imposition of Western sanctions in 2014, following Crimea annexation. And China has also maintained some economic relations with North Korea and Iran, thereby undermining the effectiveness of international sanctions.

Sino-Russian ties have indeed strengthened over the past few years, partly driven by (geo)politics but also by an economic rationale. Both countries have complex relations with the US and other Western nations and do not like Western (NATO) interference in their backyards. Moreover, China has a great need to import all kinds of commodities such as oil and gas, (precious) metals and wheat that Russia can deliver.

From that perspective it is a win-win situation for both countries to intensify these ties, because that would help China to safeguard essential commodity supplies and Russia to offset the potential impact of Western sanctions. In fact, China has already stepped up gas imports from Russia, while Beijing just decided to increase wheat imports from Russia. Part of the bilateral trade is done in roubles or yuan and the share of that could be raised as well, shielding these trade flows from international sanctions. In fact, Sino-Russian bilateral trade has increased significantly since the covid-19 related drop in early 2020, to an extent that goes beyond a post-pandemic catch-up (see chart). We should add that part of this pick-up is a price effect.

China’s support also comes in other forms, with Russia allegedly being the largest recipient of Chinese official loans. Policy banks such as China Development Bank or the Export-Import Bank of China could probably continue doing that while being relatively shielded from sanctions.

That said, China probably has to act carefully, given its own complex relations with the US and the West (partly shaped by its own longer-term territorial aspirations). China already faces Western sanctions (Hong Kong, Xinjiang) and still has to deal with heightened US tariffs stemming from the trade war initiated by the Trump administration. And while China is the largest export destination for Russia (around 15%), Russia is not a big export market for China (export share of around 2%) – with the US and other Western countries (besides EM Asia) being much larger export partners. All in all, China has to weigh the costs and benefits of (secretly) supporting Russia versus managing relations with (and preventing additional punishment from) key trade partners. US president Biden commented after Russia’s invasion that any country that would back Russia would be ‘stained by association’, without naming China explicitly.