Russia-NATO tensions: What do they mean for the economic outlook?

Global Macro: Europe would be hurt the most by an escalation of tensions – In our Energy Monitor last week, we described how Russia-NATO tensions over Ukraine could trigger further turbulence in already tense and volatile energy markets.

Our take is that the most likely scenario (with 75% probability) is for a continuation of current elevated prices, but that further dramatic price spikes or disruptions to physical supplies – triggered for instance by a complete halt in Russian gas exports to Europe – have a very low probability. Despite the low probability, we think it is worthwhile to think through some of the macro implications, should one of these more negative scenarios materialise.

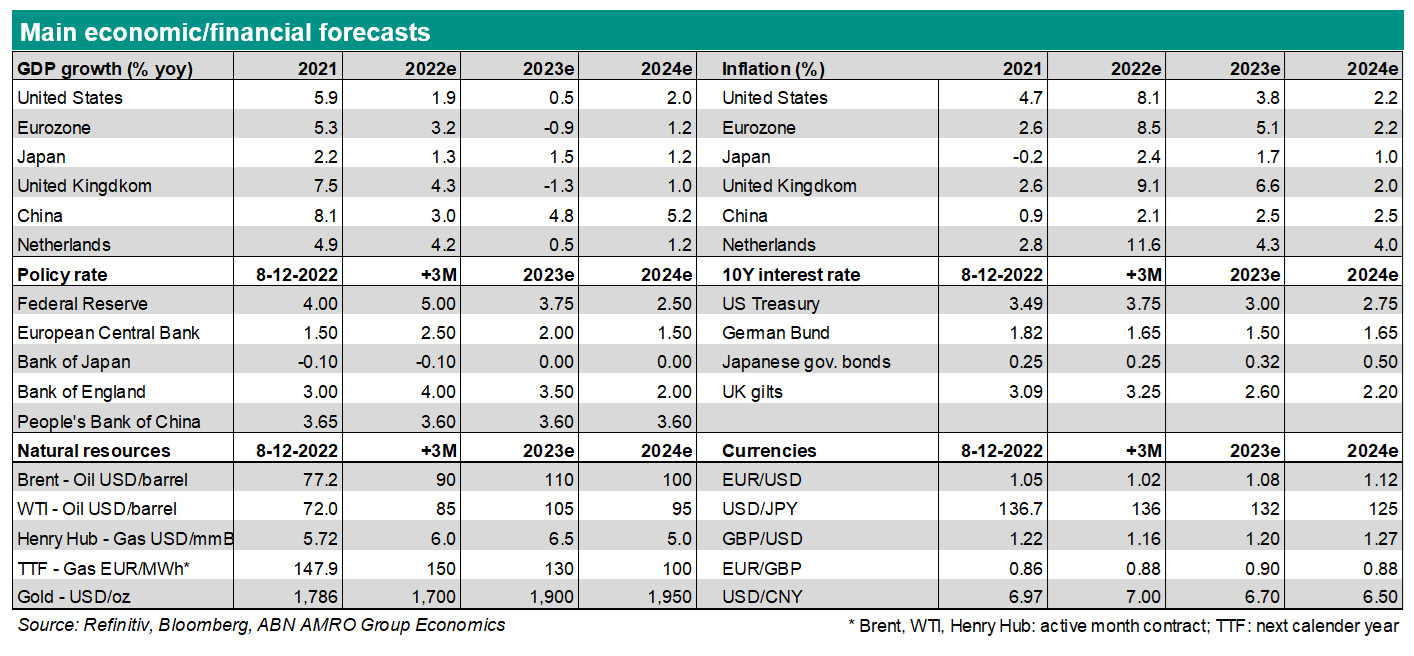

In the most benign scenarios, the global economy is likely to evolve in line with our base case, i.e. we expect a resumption of above-trend growth following the current Omicron-induced soft patch, but with bottlenecks and (increasingly) tighter financial conditions posing headwinds. See our January Global Monthly, published earlier this week, for more on our base case macro views.

In the below, we focus on the implications of energy price shock and supply disruption scenarios, which we judge collectively have a 10% probability. In big picture terms, the primary impact would be on Europe, with some advanced Asian economies likely also being impacted by price spill-overs. The US is relatively insulated from the effects, with only a modest boost to already-high inflation and a small hit to growth from spillovers, though the impact would be bigger in the most negative scenario (<5% probability) where oil prices also surge.

In the eurozone, the impact on growth and inflation would be significant, though the extent to which will depend crucially on whether governments (partly) compensate households and companies for jumps in energy prices. Russia is a major energy supplier to Europe: roughly 30% of Europe’s oil imports is from Russia and about 60% of Europe’s (extra regional) natural gas imports. Looking at the largest eurozone countries, Germany and Italy are the most dependent on gas from Russia (share in total natural gas imports around 65% and around 45%, respectively), while France gets most of its natural gas from other countries (share from Russia is around 15%). However, with energy markets tightly integrated in Europe, the price effects of any shock to supply will likely be felt by all.

The US is a net exporter of both oil and gas, and is therefore largely insulated from external supply disruptions, though it can still be affected by price spill-overs. China is a net importer of gas, but it currently enjoys a surplus in LNG stocks and has even been selling some of this surplus recently. Japan and Korea do import some oil and gas from Russia, but the share in total energy imports is limited. Nevertheless, the LNG prices paid by Japan and Korea – specifically that which is not subject to long-term contracts – is tightly linked to those of gas prices in Europe. This is because, when supply is tight in Europe, it competes with Asia for LNG on the global market. As such, Japan and Korea might also be significantly impacted by a surge in European prices, though the degree to which it is affected will depend on just how much non-contracted gas it needs, which as in Europe depends on the severity of the winter.

Negative scenario (5-10% likelihood): Stagflation as Russia halts gas exports to Europe

In this scenario, an invasion by Russia into Ukraine triggers very stringent US/EU sanctions on Russia, with a potential retaliatory halting of gas exports to Europe. We judge the probability of a halt in Russian gas exports to be low, given that there is no precedent for Russia reneging on supply commitments, and that it would also be harmful to its own interests. In this scenario, Europe would attempt to import more LNG as well as to ration gas demand. Even if all LNG-import terminals were fully operational, it would only replace 2/3rds of contracted Russian gas imports. And since Europe would compete with other consumers, mainly in Asia, it is plausible that it would not reach full import capacity, especially during the winter months.

Energy supply would therefore need to be rationed, in particular for industry. Prices of natural gas would jump significantly higher, and reach new record highs for a large part of the forward curve. The TTF monthly contracts could trade above EUR 200/MWh for an extended period, i.e. higher than the spikes we have seen recently, and with peak prices significantly higher. Electricity prices would also jump throughout Europe, with power generation in a number of countries largely dependent on gas fired plants. In fact, with the phasing out of nuclear and coal, some countries are expanding their use of gas as a power source, accompanying the shift to renewables.

In this scenario, we judge that Germany and Italy’s industrial sectors would be particularly vulnerable to rationing, with activity subject to temporary halts for some sectors. Combined with the drag on consumption from further upward inflationary pressure (reducing real incomes), eurozone GDP is likely to contract for one or two quarters, depending on the duration of the supply disruptions and the price pressures. Given the estimates for gas prices above, we would expect inflation to be around 1.5-2 percentage point higher on average this year compared to our base case (of 2.5%), and for GDP growth to be roughly 2-3 percentage points lower than in our base scenario (of 3.7% growth).

For Japan and Korea, we view physical supply disruptions as unlikely in this scenario, though inflation would likely be boosted by price spill-over effects, and this could well have a dampening effect on demand. For the US, we would expect Henry Hub gas prices to bounce higher again, though unlikely to levels beyond recent historic ranges. As such, inflation would be around 0.2pp higher than in our base case this year (4.6%). Growth would also likely be lower – in the order of 0.2-0.3pp – largely on the demand spill-over effects from Europe and Asia, and from tighter financial conditions. However, the direct impact on growth would be limited.

Very negative scenario (<5% likelihood): An even bigger escalation could cause a global bottlenecks crisis

In this scenario, a halt in Russian gas exports to Europe would be accompanied by a halt in oil exports. Roughly 50% of the Russian oil and condensate exports are shipped to Europe. The three biggest importers are Germany, the Netherlands and Poland. However, even in case of an export ban towards Europe, we believe the effects will be less hefty than with natural gas, with Europe likely able to import its crude and condensates from other parts of the world. Nevertheless, this would still lead to significantly higher oil prices. This would come via both a rise in risk premium, and temporary mismatches in the supply and demand sphere. Oil prices would be trading above USD 100/bbl and in case of serious supply worries even head for a new test of the all-time high (USD 149/bbl). Due to tighter market conditions, this situation could hold for the rest of the year.

For the global economy, we would expect the effects on growth and inflation described in the previous scenario to be intensified, with the US likely to be much more affected, as jumps in gasoline prices and even higher inflation broadly would likely weigh on consumer confidence. The need for increased shipping capacity as European oil imports are redirected from Russia to other regions would likely put additional pressure on already strained global shipping infrastructure. This would add to the many bottlenecks currently weighing on global industry, and intensify inflationary pressures more broadly. The growth effects could be amplified by the need for potentially even tighter central bank policy that might be needed to contain inflation expectations. (Bill Diviney, Aline Schuiling, Hans van Cleef)