Global Monthly - What if interest rates rise much more quickly?

We have made only modest downgrades to our growth forecasts on the back of the Omicron wave, but much bigger upgrades to our inflation forecasts. Alongside surging wage growth in the US, this has led us to bring forward our expectation for Fed rate hikes to March – with the risk of an even steeper rise in rates. We explore the impact of an alternative scenario, where the fed funds rate rises to as high as 4% next year: on the US economy, bond markets, as well as the potential spill-over effects to the eurozone.

Co-author: Nora Neuteboom

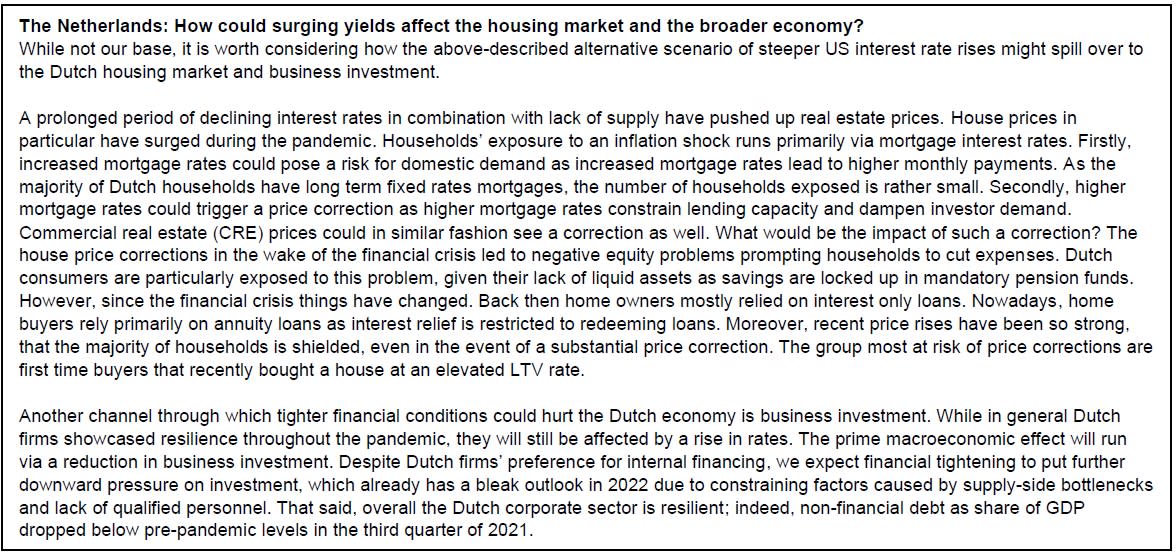

With infection waves looking to have peaked in major advanced economies, and the few countries that reimposed restrictions starting to loosen them once again, the spread of the Omicron variant has proven to be more benign in its impact on the economy than feared. This month, we have made relatively modest near-term downgrades to our growth forecasts, chiefly on the back of a delay in the services recovery and in the resolution of supply-side bottlenecks. At the same time, we have made much bigger upgrades to inflation forecasts, particularly in the US and the eurozone. Indeed, the effect of Omicron on the policy outlook has, if anything, been to strengthen the case for an earlier tightening in monetary policy. As such, we have again brought forward our expectation for the start of rate rises in the US. We continue to expect the ECB to chart a very different course than that of the US Fed – with ECB rate hikes still perhaps years away – but the eurozone will not be immune to rate rises in the US. We have already seen the beginnings of this, with 10y bund yields last week symbolically breaking back into positive territory for the first time since May 2019. In this month’s Global View, as well as giving updates on how Omicron has altered our view on the outlook, we will explore how markets and economies would respond to a potentially much steeper rise in interest rates than we currently have in our base case.

Omicron impact: Growth downgrades; inflation upgrades; bringing forward interest rate rises

In growth terms, the main impact of Omicron has been to delay the services recovery. For the most part, this has come on the back of voluntary consumer caution, with visitor traffic to retail and recreation establishments falling back in most countries. For some eurozone countries (notably the Netherlands and Austria) and a number of cities in China, there were even outright lockdowns for a time. In the eurozone and China, we have lowered our 2022 GDP growth forecasts 0.2pp to 3.7% and 5.1% respectively. But with the recovery pushed further out, this has the effect of lifting our 2023 growth forecasts, to 2.6% and 5.3% respectively. For the US, we have made a slightly bigger downgrade to 2022 growth – to 3.8% from 4.1% previously – but keep our 2023 forecast unchanged at 2.3%. Similar to the eurozone and China, the services recovery will pushed further out, though the positive effect of this on 2023 growth will be offset by weaker government spending following the failure of Biden’s Build Back Better plan, and the pass-through of Fed rate hikes.

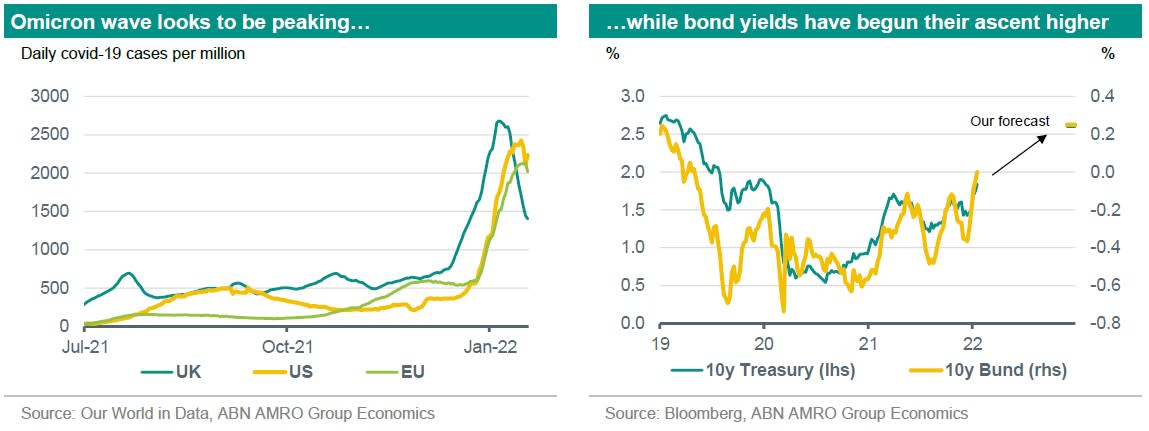

Indeed, we have made much bigger changes to our inflation projections, partly on the back of Omicron, and in the US specifically, partly because inflationary pressures have broadened and become more durable. The effect of Omicron on inflation is chiefly in the delayed easing of supply-side bottlenecks. In advanced economies, increased worker absences for isolation reasons are putting renewed strains on already stretched workforces. In China, the government’s zero-covid policy has led to renewed local lockdowns (that said, the latest PPI data from China suggests some modest easing in price pressures for now). Indeed, while the Omicron wave looks to have peaked in advanced economies, the situation in China is radically different, and the possibility of broader lockdowns in China to contain the spread of Omicron remains a major risk to the outlook, both for growth (to the downside) and inflation (to the upside).

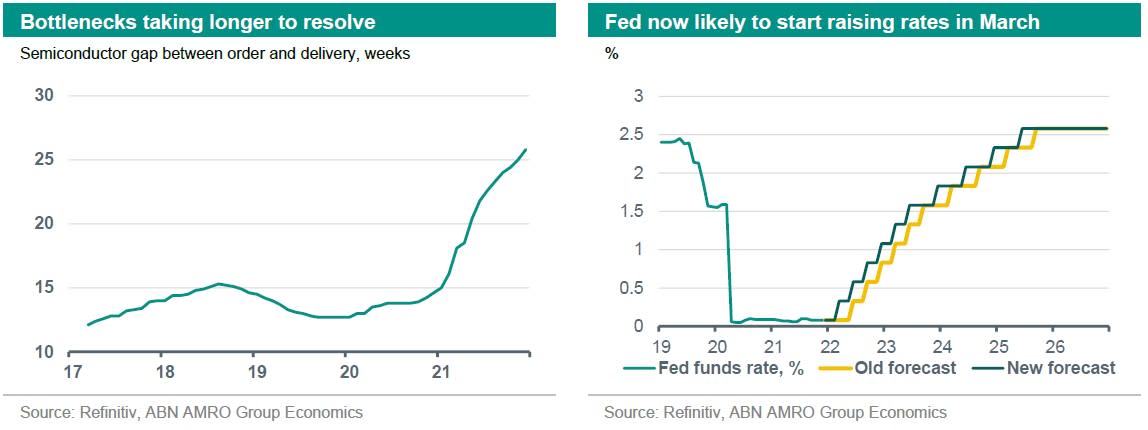

In the US, continued upside surprises to inflation have led us to bring forward our expectation for the first Fed rate hike to March, from June previously. We now expect inflation to average 4.6% in 2022 in the US, up from 3.9% in our December projection. This is on the back of elevated pipeline pressures from producer prices, but more importantly – and more durably – from the labour market. With unemployment now sitting below the level consistent with full employment at 3.9%, wage growth accelerated further in December, to 6.1% on a 3m annualised basis – double the pre-pandemic average of c.3%. Elevated inflation and a tight labour market are proving to be a potent cocktail in the US, and have significantly raised the risk of a prolonged wage-price spiral.

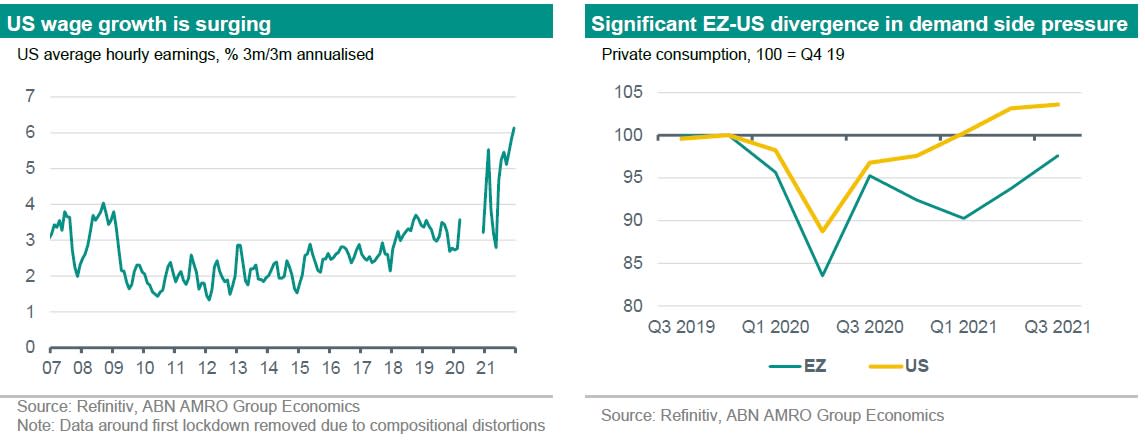

To be clear, the picture in the eurozone continues to differ substantially. While we have also raised our 2022 inflation projection here, to 2.5% from 1.7% previously, this is chiefly on the back of more sustained goods and inflation. Inflationary pressures stemming from the domestic demand side remain absent in the eurozone, with the volume of private consumption still around 2.5% below pre-pandemic levels as of Q3 last year, whereas in the US it was 3.6% above pre-pandemic levels. Moreover, structural rigidities – such as the prevalence of multi-year, collectively negotiated wage agreements – continue to keep a lid on near-term wage growth, despite labour market tightness in countries such as the Netherlands and Germany. Even the recent jump in inflation is likely to have only modest upward effects on wage growth, with indexation regimes applying to a small minority of workers. As such, despite our forecast upgrade, our base case continues to be for inflation to fall back to below the ECB’s 2% target by end-2022. Given these differences, we expect a much earlier and steeper rise in interest rates in the US than in the eurozone. For the US, we now expect four interest rate rises this year, up from three previously, and a further three rate hikes next year. This will bring the fed funds rate back to the pre-pandemic target range of 1.5-1.75% by mid-2023. For the ECB, while from Governing Council members signal greater vigilance over inflation, we continue to think rate hikes on our forecast horizon (to end-2023) are unlikely.

Still, as we flagged in our Global Outlook last month, the eurozone is significantly impacted by spill-overs from the US inflation problem, and this will intensify as the year progresses. Moving in tandem with US Treasury yields, Bund yields have already risen more quickly than our forecasts, and given the earlier start to Fed rate hikes, we now expect Bund yields to rise to 0.25% by end-2022, up from our previous expectation of 0%. Rising rates naturally put a dampener on growth through various channels, from housing to business investment. These effects will be masked during the post-pandemic recovery phase, but will weigh on growth in the longer run.

But what if interest rates have to rise a lot more?

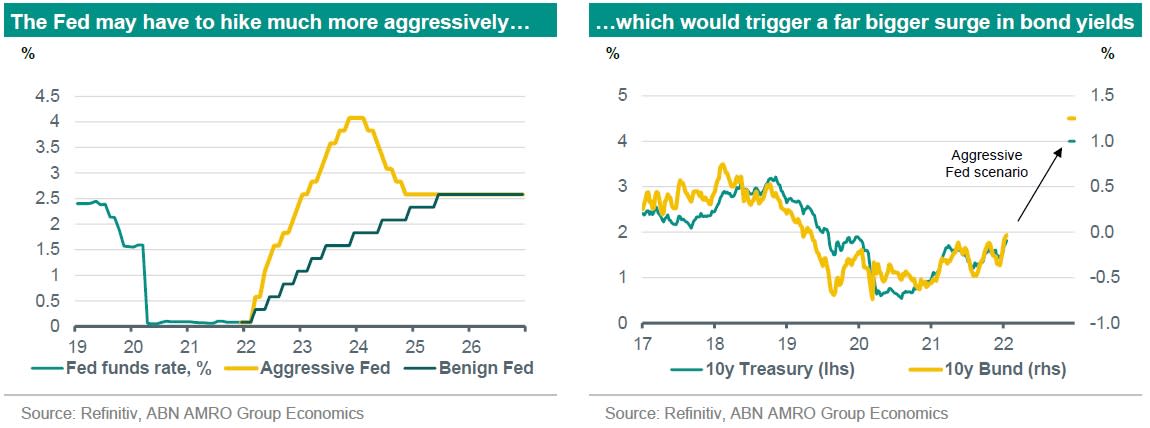

While we have again brought forward our expectation for the start of Fed rate hikes, even this more aggressive profile is conditioned on inflation falling back significantly over the coming year, albeit settling above the Fed’s 2% target. But what if inflation doesn’t fall back, or falls back by less than we expect? We think the Fed would respond much more aggressively in this scenario. This would involve raising rates at more than double the pace of our base case, and peaking as high as 4% by end-2023 – well above the estimated nominal neutral rate of c.2.5% (see chart below).

The first round impact of this would be to trigger a massive (and probably quite sudden) tightening of financial conditions. The 10y Treasury yield – which typically peaks at around the eventual peak of the fed funds rate – could surge to as high as 4% by the second half of this year. Our estimates suggest that, at a 4% 10y Treasury yield, equity markets would be due a severe correction, with credit spreads also likely jumping sharply. Such a shock to financial conditions would naturally be a big hit to the economy, via numerous channels. The housing market – which turned red-hot through the pandemic – would likely see a correction lower on the back of surging mortgage rates. Many business investments would be rendered unviable by higher interest rates. And the fall in equity markets would have a major negative wealth effect. The net effect of all of this would indeed be to bring inflation back down, but with the unfortunate side effect of a significantly weaker economy – and perhaps a US recession by later this year. The Fed could slow the pace of rate hikes if this looks to be inducing a severe recession, but with its priority to tackle inflation, would be much higher.

Spill-over to the eurozone would be even bigger in this scenario

As with our base case, there are significant spill-over effects to the eurozone and indeed the global economy. Weaker demand from a slowing (if not contracting) US economy, alongside a hit to EM growth (see from our Outlook), would be one major spill-over, though a weaker US economy could actually provide some relief to buckling supply chains, with excess goods consumption having compounded these difficulties over the past year. A much more negative spill-over is likely to be via financial conditions, both from surging bond yields and weak equity markets. We are likely to see such market moves mirrored in Europe, albeit on a smaller scale. For bund yields, we would see an even bigger jump than in our base case, to around 1.25%. This would be the highest yields have been since 2014, when the ECB first embarked on its asset purchase programme. Given the very different macroeconomic environment in the eurozone, the ECB would likely push back against this surge in bond yields by stepping up asset purchases, while risk aversion stemming from global falls in equity markets would also support demand for safe havens such as Bunds. This would ultimately bring yields down to a still-elevated level of around 0.8%.

A further offsetting factor would be a weaker euro, which would be weighed by an even larger gap between US and eurozone bond yields. Even in our base case, we expect EUR/USD to fall to 1.05 by end-2022, and to parity by end-2023. In this more aggressive Fed scenario, we would expect this move lower in EUR/USD to be hastened, although this effect could be later blunted as markets price in a bigger hit to the US economy from surging rates. A weaker euro would boost eurozone export competitiveness, offsetting some of the dampening effect on activity of higher interest rates and the expected slowdown of global growth and world trade in this scenario. While the tightening of financial conditions would therefore not be as big in the eurozone as in the US, it would still lower economic growth, likely to close to zero as compared to the above-trend growth we expect in our base case.