Rates Conviction - EU defence spending could shake EGB market

Recent comments by Trump regarding Russia and Europe have suggested a diminished US commitment to NATO, prompting European nations to significantly increase their defence spending.

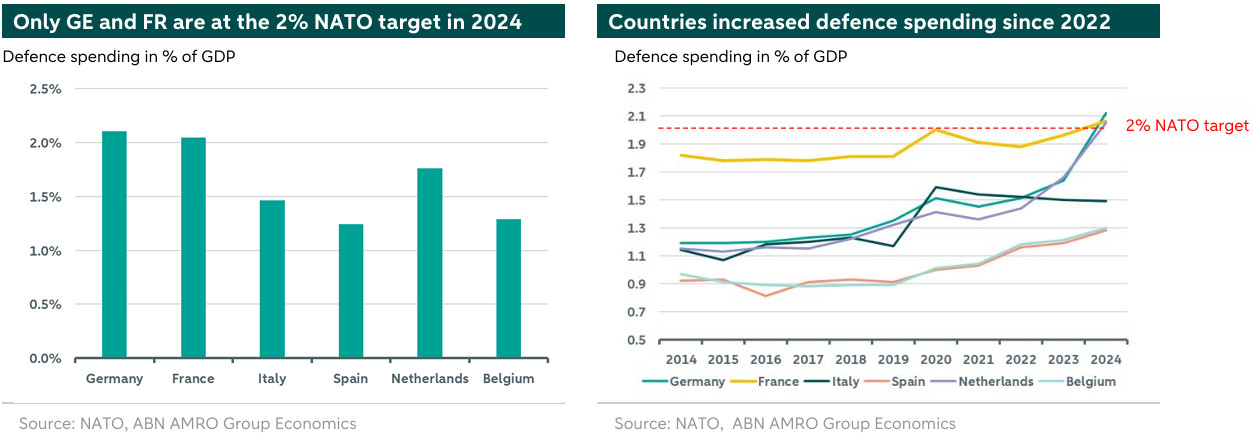

Among the largest eurozone countries, only Germany and France are projected to meet NATO's 2% defence spending target in 2024, with the Netherlands nearly reaching the benchmark.

Countries like Italy, Spain, and Belgium, which currently fall short of the 2% target, may be required to substantially increase their defence investments in the coming years.

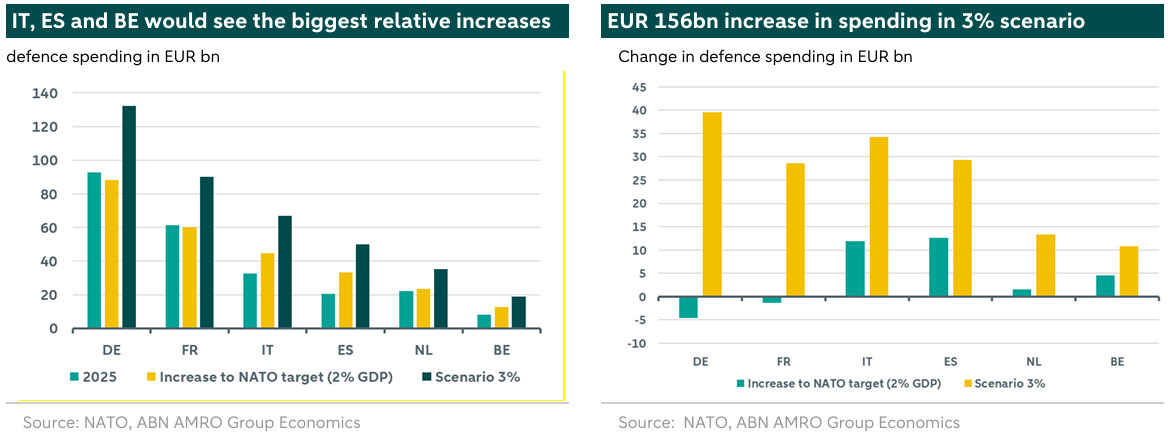

Assuming a scenario of 3% NATO target, the increase in investment spending for the EU big-6 would need to increase by EUR 156bn.

Various financing options were discussed at the Paris defence summit, including the exclusion of defence expenditures from EU fiscal rules, utilizing existing EU funds and facilities, and creating a new EU defence fund financed through joint debt issuance (similar to the NGEU program post-COVID).

The first option is likely to have the biggest impact in terms of market reaction, as rising defence expenditures would exacerbate existing fiscal and debt concerns in Europe

This scenario would likely lead to additional bond issuance and higher term premia, resulting in increased bond yields.

Conversely, utilizing existing EU facilities or creating a new EU defence fund through joint debt issuance would benefit mostly peripheral countries…

….Larger economies like Germany and France would bear a bigger portion of the financial burden, potentially resulting in an underperformance of their bonds compared to those from smaller economies.

However, a long-term financing solution to establish a European defence could also renew investor confidence on Europe’s capacity to come together as a Union.

All else equal, higher defence spending could mean the ECB pauses rate cuts a little sooner, but the case for a prolonged rate cut cycle remains very much intact.

NATO 2% defence spending target still far away for several EU countries

Donald Trump has made it clear since winning the US presidential election that it is no longer a foregone conclusion that the US will act as protector of the other NATO countries. In particular, the fact that many NATO members have spent less than 2% of GDP on defence for years is a thorn in the side of the new US president. In recent weeks, this discussion has become very tangible for the European members of NATO as the US has, for the time being, not involved the European Union in peace negotiations with Russia regarding the war in Ukraine. This has given Europe a reality check that it needs to stand more on its own feet in terms of defending its own borders.

Based on NATO data [1] it appears that only a few of the NATO members meet the objective of spending at least 2% of GDP on defence. These data show that Poland has the highest relative defence budget and that the Baltic states also have relatively high defence budgets. The US itself spends an average of about 3.5% of its GDP on defence, while the United Kingdom has also met the target in recent years.

Of the six largest countries in the eurozone, only Germany and France met the target in 2024, while the Netherlands was close to this target. Based on the NATO data, the Netherlands has reached the target in 2024, but because GDP increased more than anticipated in the NATO data, the actual spending fell below the 2% target in 2024. But where France has kept spending relatively stable at around 2% in recent years, Germany and the Netherlands have, after the outbreak of the war in Ukraine, brought spending to the desired level or close to it (see right graph below). For Italy, Spain and Belgium, the defence budgets are still far from the 2% target, although Spain and Belgium have increased the spending during recent years as well (see right graph below).

Countries with a relatively low defence budget will bear the brunt of an increase

Now that it is likely that the defence budgets of the European NATO members will have to increase, we have analysed what the size of changes in the defence budgets will be, measured in euros using two scenarios. The first scenario involves an analysis in which all European NATO members set the defence budget at the NATO target level of 2% of GDP. However, this is likely to be insufficient due to the current geopolitical situation and that budgets will continue to rise, which is why we have also analysed a scenario in which budgets are set at 3% of GDP. Incidentally, Donald Trump has also called for higher targets on several occasions (up to 5% target), but we currently consider it unrealistic given current budget constraints in Europe.

Because both Germany and France are already above the 2% defence spending target, these countries do not need to increase their defence budgets in the first scenario. In theory, these countries could even lower their budgets because they currently spend more than 2% of their GDP on defence. In this scenario, the Netherlands will have to increase its budget by EUR 2bn, while Italy (EUR 12bn), Spain (almost EUR 13bn) and Belgium (EUR 4.5bn) in particular will have to increase defence spending considerably to reach the target of 2% of GDP. Moreover, these extra expenditures will be structural because the basic assumption is that the 2% standard will have to be met every year.

In the second scenario, in which the defence budgets for all European NATO members are set at 3% of GDP, defence spending will significant increase for all countries. According to our analysis, total expenditures on defence for the six largest EU countries will increase by EUR 156bn to EUR 400bn (based on 2025 GDP estimates), with Germany having the largest increase in absolute terms (from EUR 93bn to EUR 132bn). But here too, the countries that currently have the lowest defence budgets based on GDP will have to make a greater effort.

Overall, it is clear that government spending will increase in both scenarios. Several countries have already announced plans to gradually increase defence spending in the coming years, which means that the impact on the budget deficit and the possible increase in debt issuance will also be gradual. However, some of the countries mentioned are already struggling to reduce their budget deficits and their debt-to-GDP ratios. Italy, Belgium and France have, for instance, been placed under EU supervision through the EU's Executive Deficit Procedure, which means that this additional, structural expenditure on defence will exacerbate these countries’ fiscal challenges.

In the following paragraphs, we will discuss the possibilities for financing this additional expenditure and the potential impact of these various options on fixed income markets.

1) Excluding defence expenditures from the EU fiscal rule

One direct approach to finance European defence expenditures is at the national level. Given the current lack of consensus on joint debt issuance, this appears to be the most feasible option in the near term. The idea proposed by EC president Ursula Von Der Leyen goes in that direction. She proposed to trigger an emergency clause that would allow military spending to be exempted from the EU's stringent budget deficit limits. This would enable EU member states to finance defence spending through higher deficits without breaching the fiscal rules. Countries like Spain have expressed reluctance to jeopardize their good fiscal performance for higher defence spending. But with the geopolitical environment rapidly changing, and the formation of the which has agreed to strengthen Europe’s defence, the pressure to raise spending is likely to increase.

One obvious drawback from this is the impact on countries’ deficits and subsequently on borrowing costs. In recent months, markets have begun to scrutinize Europe's fiscal figures, leading to higher term premia due to concerns about public finances spiralling out of control. Higher defence spending would also result in a greater government debt supply that the market would need to absorb, in addition to ongoing quantitative tightening (QT). Consequently, even if defence expenditures were excluded from fiscal rules, the impact on national debt levels would be tangible as borrowing requirements would rise. As a result, this option is likely unsustainable in the longer-term given current fiscal profiles of most European countries.

What would be the impact on the EGB market?

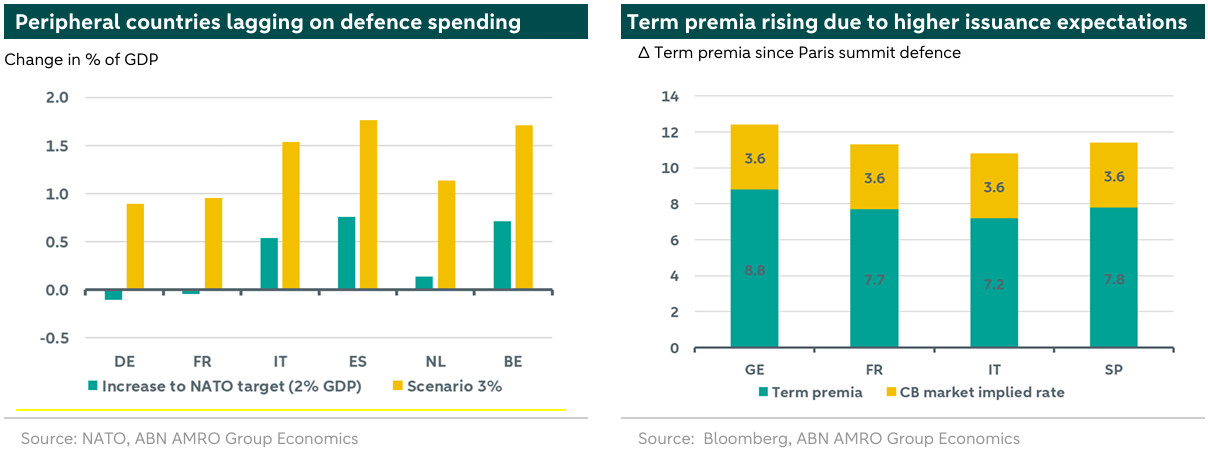

Assuming that national governments are required to individually shoulder the costs of increased defence spending, countries like Germany and France—which already meet the 2% NATO target, as described above—would be least affected. Even with an increase to a 3% NATO target, the impact as a percentage of GDP would be less significant for these nations compared to others. Countries like Italy, Spain and Belgium would need to ramp up significantly their defence investment (as shown in the left graph below) and are already among the highest indebted countries in the Eurozone. Thus, these countries, who are also placed under the EU’s Excessive Deficit Procedure, could see their efforts to reduce deficits stalled, likely triggering higher risk premia and exerting upward pressure on bond yields.

In our view, this financing approach could heighten current fiscal concerns among investors, adding considerable upward pressure on EGBs overall, particularly for heavily indebted countries. Following the Paris Defence Summit, long-term EGB yields already increased as the market anticipates higher bond issuance on the back of higher government spending. This led to a rise in term premia, as shown in the graph on the right below.

2) Make use of current EU programmes

Some European politicians pointed to the possible use of existing EU programmes that can be quickly deployed to finance (part of) the increase in defence spending. The idea would be to redirect parts of cohesion or structural funds towards defence-related investments. For instance, the NGEU program (which is currently ongoing and offers the largest financing pool with almost EUR 800bn in total) could be such a tool. Given the existing infrastructure and success of the NGEU program among investors, extending it to focus on European defence seems a straightforward and effective option. Looking at the current disbursement, only EUR 300bn has been disbursed so far out of the EUR 640bn allocated to member states. There is also EUR 100bn left in the envelope to be allocated to all among member states. Furthermore, the programme officially runs until the end of 2026, which means that the use of this programme is currently temporary, but could theoretically be extended.

However, redirecting the undistributed NGEU funds towards defence spending would require unanimous approval from EU member states (including from more obstructionist, Russia-leaning states such as Hungary), alongside potential legal and political reforms to the existing NGEU framework. While theoretically feasible, such reallocation presents a complex challenge that will take some time.

Various European leaders such as the Spanish Minister of Economy, Carlos Cuerpo, also suggested expanding the European Investment Bank’s (EIB) defence-related investments. Other option is to make use of the European Stability Mechanism (ESM), worth more than EUR 400bn, originally established to support countries during the Eurozone crisis. This approach could provide a more politically palatable solution by tapping into existing financial structures without the need for additional joint debt.

Other European defence facilities such as the EDF, EDIP, and EPF can serve as additional financing tools. However, those EU defence tools face several big challenges (as discussed in this European ),the most important one being the limited size. Adding up all the individual EU defence facilities we reach around EUR 25bn with both EDF and EPF set up to go through 2027 only, which is far from meeting the additional EUR 500bn spending recommended by the European commission for the next decade.

What would be the impact on the EGB market?

Assuming that part of the NGEU program could be re-allocated to finance defence spending and an increase in other EU defence spending facilities, the immediate financial pressure on more fiscally vulnerable EU member states could be alleviated. Furthermore, the market may perceive the increased defence spending initiative as a strategic shift towards more integrated EU defence capabilities. While this could be seen as a positive move for EU stability and security, the financial implications for larger economies may raise concerns about their fiscal health. Indeed, given the limited funds available, additional contributions from member states would likely be required. As these contributions are typically based on a country's gross national income (GNI), larger economies like Germany and France would bear a bigger portion of the financial burden, potentially resulting in an underperformance of their bonds compared to those from smaller economies.

3) New EU program facility financed by joint debt issuance

Another financing option discussed at the Paris defence summit was the creation of an EU defence fund programme. Issuing EU debt, similar to what was done with the NGEU post-covid recovery instrument, is another option available to Europe. This time even the fiscally conservative Germany would be on board as the most likely next German chancellor, Frederich Merz, is open to it. However, numerous national political hurdles must be addressed, especially with ongoing federal elections (see our ). This option could free up national budgetary resources and offer long-term funding stability while bolstering the domestic defence industry. Nevertheless, achieving EU consensus for such a program will be challenging and time-consuming, making it more of a medium- to long-term solution rather than an immediate fix for increasing defence spending.

To address potential moral hazard, adjustments could be made so that countries not meeting current NATO targets, like Italy, Spain, and Belgium, must first achieve the 2% target before benefiting from this financing pool. Indeed, in terms of fairness, countries already meeting the target might be reluctant to finance other countries' defence underspending. Furthermore, despite the urgency, the idea of joint debt is still politically sensitive, especially among the most fiscally conservative countries in Northern Europe. Therefore, this option may not be the quickest and easiest to implement yet.

What would be the impact on the EGB market?

Assuming implementation similar to the NGEU program, this initiative would primarily benefit peripheral economies, particularly smaller ones like Spain and Belgium, which currently fall short of meeting NATO targets. Access to a new funding pool could help them achieve these targets. In such a scenario, we expect peripheral countries to outperform, with 10-year spreads tightening further from current levels, while Germany would underperform. Similarly, Dutch bonds are likely to underperform the rest of the EGB market, as their borrowing costs are lower than the EU's, reducing their need to utilize this program, as was the case with the NGEU.

And what about the impact on growth, inflation and the ECB?

Our current base case sees the eurozone economy slowing later this year and in 2026 on the back of the US tariff hit to exports, with the ECB expected to continue cutting rates until the deposit rate reaches 1% in early 2026 (we expect a temporary pause in cuts at the April Governing Council meeting). This base case does not assume a significant rise in defence spending beyond what is already in government programmes.

It is too early to draw concrete conclusions given how fluid the situation is, but all else equal, higher defence spending on the scale described above would put upward pressure on growth, inflation, and – depending on the timing – could lead to the ECB pausing rate cuts sooner than our current base case. We note however some caveats. First, any increase in spending is unlikely to fully offset the slowdown from the US tariff threat, which if anything is tilting towards a more negative scenario than our base case. Second, to the extent that other EU funds are redirected towards defence spending, this would not lift growth beyond our base case, as it would mean less spending in other domains. And third, it would take time for the EU defence industry to ramp up and to respond to higher spending, meaning that initially a significant portion of higher spending is likely to ‘leak’, i.e. be spent on higher imports (mostly from the US). This will dampen the growth and inflation impact.

Conclusion

In summary, at the current stage, there remain significant uncertainties regarding the funding of the anticipated increase in defence spending. However, we think that the exclusion of defence expenditures from the EU fiscal rules appears to be the most feasible scenario in the short-term. This approach can be implemented relatively quickly and can serve as an interim measure while further discussions on establishing a comprehensive European defence framework continue. Given the budget constraints faced by most European countries, adding an additional EUR 500 billion of government spending on at the European level and financed by the individual member states, as recommended by the European Commission, might be unsustainable. This option may also significantly impact European government bond yields due to the extra spending from the additional borrowing requirements, leading to higher term premia. Therefore, joint debt issuance presents a more viable long-term financing option. The market impact would also be more contained for individual countries and could actually trigger renewed investor confidence in a more unified European Union.

To fully assess the impact of increased defence spending, it's essential to analyse its effects on the broader European economies, on the monetary policy, the spillover effect on individual countries’ deficits. This will be the focus of an upcoming note.