Global Monthly - Will the Red Sea disturbances throw disinflation off track?

Despite the continued transatlantic growth divergence, disinflation has made further progress in both eurozone and the US. On some measures, inflation is already back at central bank 2% targets. The Red Sea and Panama Canal disturbances remind us of the risk of unexpected supply shocks, but our take is that the they are unlikely to meaningfully disrupt the normalisation in inflation. Also this month: We flag the key events and themes that are likely to shape the outlook in 2024.

Global View: Red Sea shipping disruptions are likely to only marginally impact inflation

Since our Global Outlook 2024 publication in early December, the US economy has clearly slowed, the eurozone is stabilising at weak levels, and China’s growth momentum continues to be weighed by the stumbling property sector. The broad trend has been in line with expectations. However, the US economy has continued to defy expectations for an even sharper slowdown, while the incoming data suggests the risks to eurozone GDP – in the very near-term – if anything look a little tilted to the downside. What about going forward? The core drivers of activity continue to suggest a transatlantic convergence in growth patterns. The fading impulse from excess savings and a cooling labour market are likely to weigh on consumption in the US. In the eurozone, the recovery in real incomes following the easing of the energy crisis and the catch-up in wages is expected to drive a modest recovery as the year progresses. In China, while the authorities are continuing to roll out targeted stimulus and piecemeal easing, the need to deleverage holds them back from administering a bigger jolt to growth. The subdued global growth outlook makes it all the more vital that central banks make a timely pivot to rate cuts. Could the Red Sea disturbances scupper that? As things stand, we think not. But a major escalation in the Middle East could change matters.

Disinflation continues apace, but sticky wage growth in Europe bears close watching

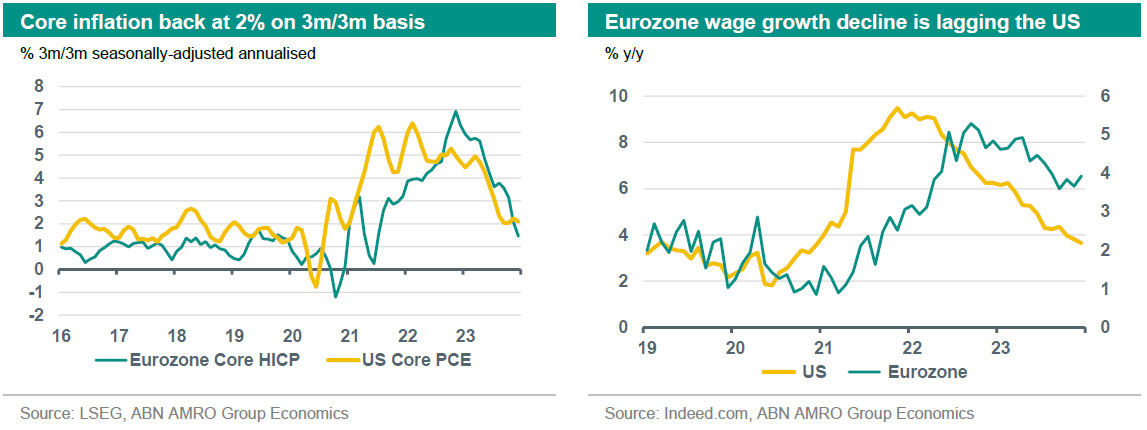

For the time being, disinflation has continued in advanced economies. On a 3m/3m annualised basis, the Fed’s preferred measure – PCE inflation – is within striking distance of the 2% target, while in the eurozone, core HICP inflation is even somewhat below 2%. It is true that the main drivers of disinflation so far – goods and energy – are starting to fade. But we already see the beginnings of a decline in services inflation. For instance, annual growth in housing rents – a major driver of inflation in the US – clearly peaked back in March 2023, at 8.3% y/y, and more timely new lease data suggest that this component will continue rapidly normalising over the coming months. In the eurozone, core disinflation has been mostly concentrated in energy-intensive components so far, but given the weak demand environment, we expect this to spread increasingly to labour-intensive services.

Key to this is going to be a timely normalisation of wage growth. In the US, some measures of wage growth have already fully normalised: average hourly earnings are growing at around 4% on a 3m/3m annualised basis, similar to before the pandemic, and unit labour cost growth was just 1.6% y/y as of Q3. The Atlanta Fed’s wage growth tracker is admittedly on the higher side, but it has also fallen sharply over the past year, and one of the Fed’s favourite measures – the Employment Cost Index – is also on a clear normalising path. Given the cooling in the labour market, we see little reason to worry that these normalising trends will reverse.

In the eurozone, the wages story is lagging the US given the later surge in inflation, and because the rise in wage growth was driven more by workers seeking compensation for the shock to their real incomes rather than being driven by a particularly tight labour market (1). Wage growth is still well above pre-pandemic levels, even according to the most timely measures such as the Indeed monthly tracker. However, the peak looks to have been set in the Autumn of 2022, and since then the Indeed tracker has been on a downtrend. Other, more lagging measures of wage growth remain elevated but look also to have peaked. With the economy much weaker than in the US, and the main driver of the jump in wage growth (the energy crisis) now resolved, we expect a much more rapid normalisation in wage growth over the coming months, thereby giving the ECB the confidence to start lowering rates in June.

Will the Houthis and the Panama drought throw disinflation into reverse? We think not

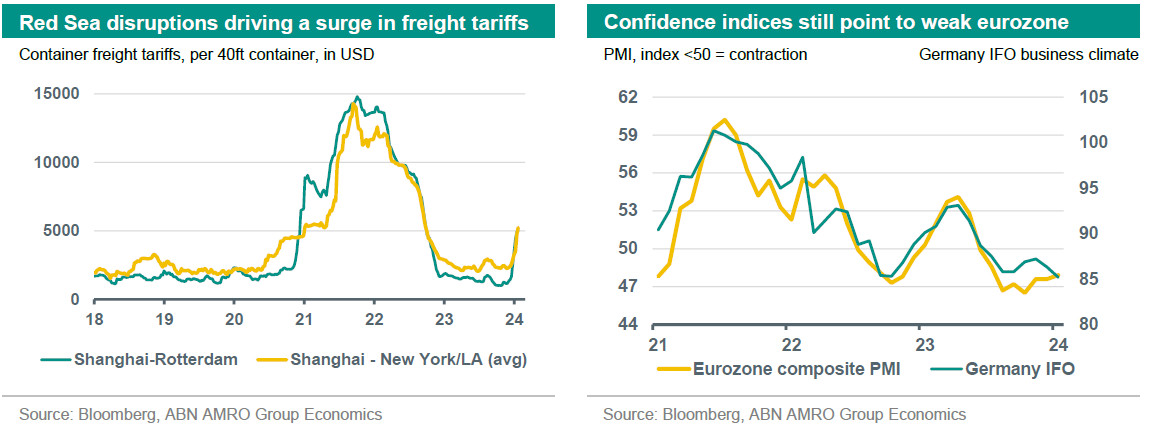

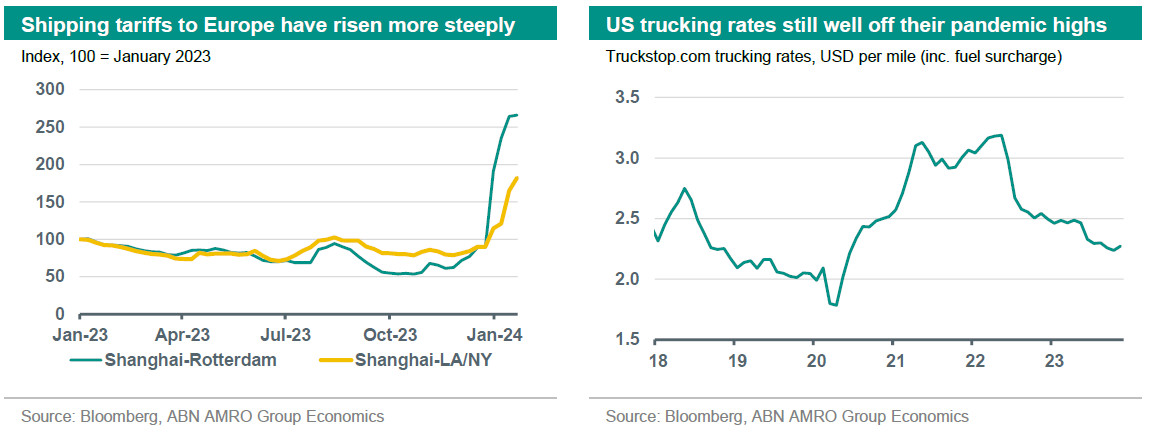

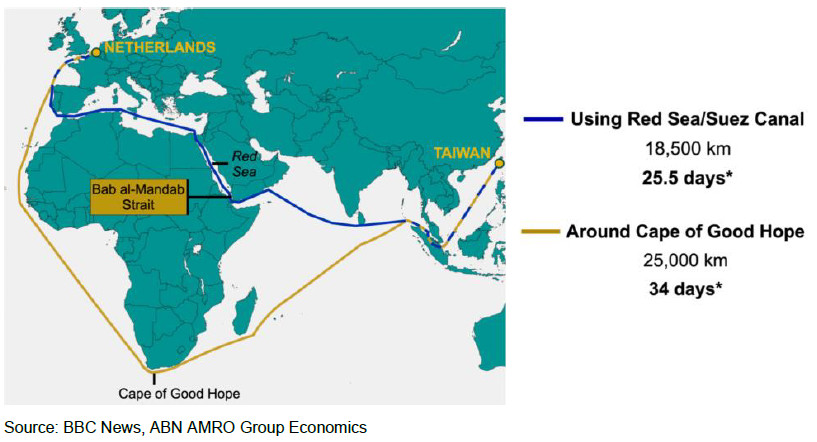

While we await clarity on wage developments, a new inflation risk has emerged: the Houthi attacks on commercial ships passing through the Red Sea. This has led to a quadrupling in shipping freight tariffs from their recent lows between China and Europe, and the potential for supply disruptions due to the diversion of ships around the much longer Cape of Good Hope route. This comes on top of the disruptions in another crucial global trade artery, particularly for the movement of goods to the US from Asia – the drought in the Panama Canal. Taken together, the disruptions have led to a quadrupling in shipping tariffs from Asia to Europe, and a doubling in tariff rates to the US. Just as we seem to have got over the pandemic and energy crisis supply shocks, is inflation now set for another supply shock-induced surge?

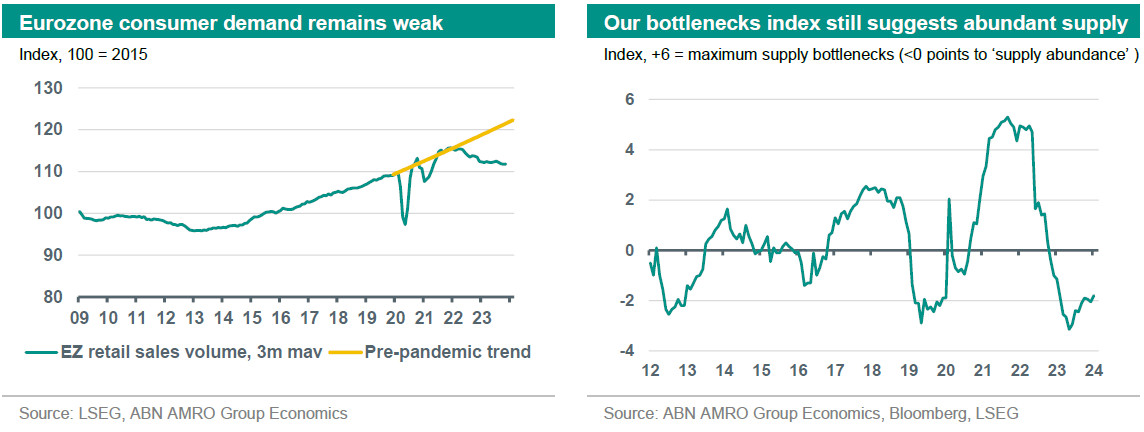

We think not, for three reasons. First, shipping costs make up a relatively small share of the cost of goods imports: according to an from 2021 (2), international shipping costs make up less than 1% of the final cost of manufactured goods. Goods themselves make up 26% of eurozone and 20% of US inflation baskets. Even then, a significant share of this is unaffected by international shipping costs. For instance, in the US, nearly half of the good in the inflation basket is cars (new and used), and medicines, which are largely domestically sourced. Moreover, shipping freight tariffs collapsed by nearly 90% in 2022, but partly due to fears of potential future disruptions or price rises (see ), this was likely not passed on to consumers. Taken together, goods importers therefore probably have enough margin to absorb the recent tariff rises, which is itself still an order of magnitude smaller than in 2021.

A second and related reason not to expect an inflation surge is that, unlike the 2021-22 period, this shock is not being accompanied by other supply shocks. Back then, it was not just shipping freight tariffs that rose: freight tariffs across transport modes (including domestic routes, such as road haulage) also jumped, and shortages of key components (such as semiconductors) led to surging prices of other input costs. These cost pressures are no longer present. Indeed, on the contrary, prices of many inputs are seeing falling prices: in Europe specifically, a massive offsetting factor is the collapse in energy prices, which is still yet to fully feed through to goods prices.

Third, even for those businesses where margins are tighter as a result of shipping tariff rises, the weaker demand environment at present means that it will be much harder for costs to be passed on. Eurozone retail volumes have been on a persistent downtrend since the end of 2021, and remain some 4% below their end-2021 peak. We are therefore sceptical that European importers will be able to pass on any extra costs. In the US, where consumer demand has been more resilient, the rise in shipping costs – and the potential for disruption – is much smaller given that the disruptions to the Panama Canal are less severe than the Red Sea/Suez Canal.

Even under the most generous assumptions, we estimate the rise in shipping tariffs – if they are sustained and fully passed on – may raise eurozone goods inflation by c1pp. This would raise overall inflation by only 0.3pp. Given the powerful offsetting factors, such as the collapse in energy prices and the downward pressure on goods prices from overcapacity in global manufacturing, this would marginally slow the disinflation trend, but it would not come close to derailing it. In the US, the impact is expected to be even smaller, given the proportionally smaller rise in shipping costs.

What about supply disruptions?

With shipping from Asia to Europe taking around 9 days longer via the Cape of Good Hope than via the Red Sea, another concern has been the potential for supply disruptions resulted from delays to parts deliveries impacting supply chains.

So far, there is limited evidence of this. Some auto makers announced production pauses for 3-10 days, although the same companies have also faced weak consumer demand, and so the Red Sea disturbances could be convenient cover for a pause. In the eurozone flash PMIs for January, the sub-index for delivery times suggests some lengthening, although the commentary that accompanied the release added the caveat:

“…various industry reports indicate that businesses are not caught off guard like they have been previously, having learned from past disruptions. Many have proactively diversified their suppliers across geographical regions and enterprises, mitigating the potential fallout from such unforeseen challenges.”

Also noteworthy is that the Houthis have said they would not target Chinese ships in their attacks (reflecting China’s neutral stance in the Middle East). This is crucial given that much of the trade that could be impacted originates from China. Indeed, the latest data suggests that around half of the traffic that typically passes through the Red Sea is proceeding as normal.

With regards the Panama Canal, while drought-related disruptions have pushed shipping costs higher, physical disruptions have been limited. Monthly transits through the canal are down by around 25%, but most of this decline has been due to dry bulk shipments diverting to lower cost routes, as canal passage fees rose. Container ships – those containing finished consumer goods – have been less affected. Where there has been an impact on container shipments, shipping companies are adapting, for instance by moving some cargo over land adjacent to the Panama canal and reloading back onto ships at the other end. This raises costs, but the risk of physical disruptions is minimised.

What if the conflict in the Middle East escalates?

At present, the main channel of impact from the conflict in the Middle East is via shipping, which – as we have argued – is unlikely to really move the needle on inflation. Another channel, which drew attention back in October when the conflict between Israel and Hamas broke out, is oil prices. While oil prices initially rose in the early stage of the conflict, this proved short-lived, and oil prices are now around 15% below where they were on the eve of the conflict in late September. But with the US and UK militaries becoming involved, the risk of a further escalation – potentially drawing Iran directly into the conflict – has risen. Should such a material escalation occur, a much steeper and more sustained rise in oil prices could occur.

Were oil to rise 35-40% above current levels – to average $110-120 per barrel in 2024 (and potentially a much higher peak) – we estimate this would add around 0.7pp to US inflation, and 0.9pp to eurozone inflation. Given the risks this would pose to inflation expectations, such an escalation could have more meaningful consequences by potentially postponing the start of interest rate cuts, which would negatively impact the growth outlook. As things stand, this remains a risk scenario, and our base case for inflation assumes only a modest rise in oil prices this year (to $90 per barrel by end-2024 for Brent crude).

-----

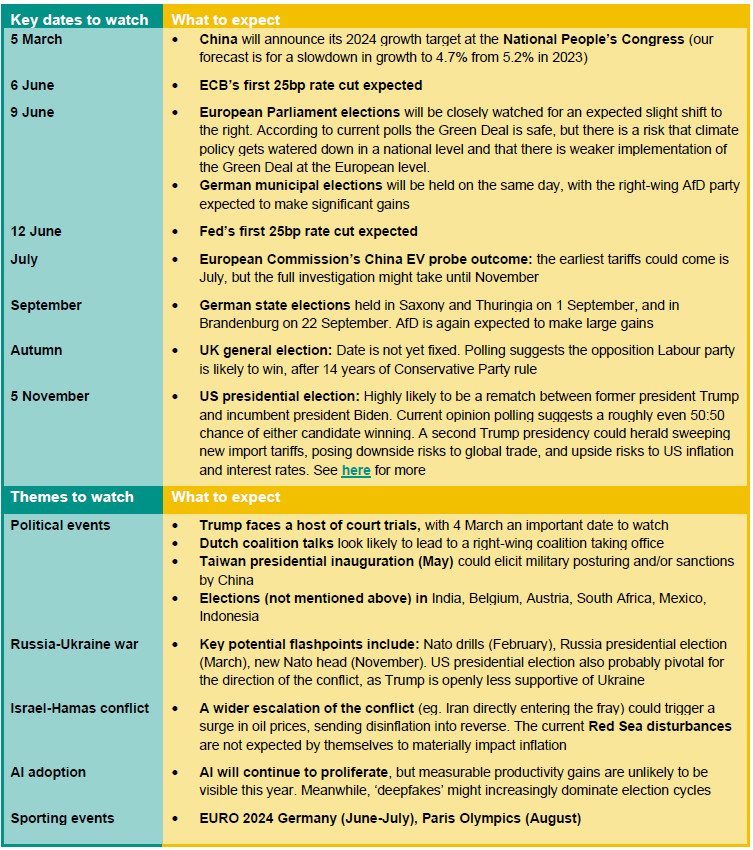

Key events & themes 2024: To supplement our , below we flag some key events that could impact the outlook in our coverage space. Below this, we describe some broader themes that are likely to dominate the news cycle.

(1) Of course, there were pockets of labour market tightness eg. in Germany and the Netherlands, but not at the eurozone aggregate level

(2) When shipping freight tariffs also surged – by a much larger magnitude.