Global industry: Europe still the weakest link

Global manufacturing PMI drops back below neutral mark. Weakness broad-based; France and Germany weak spots in eurozone manufacturing. Supply weakened more than demand in December. Input price component up again, but still well below previous peaks. Rising spot container tariffs between China and US signal trade frontloading.

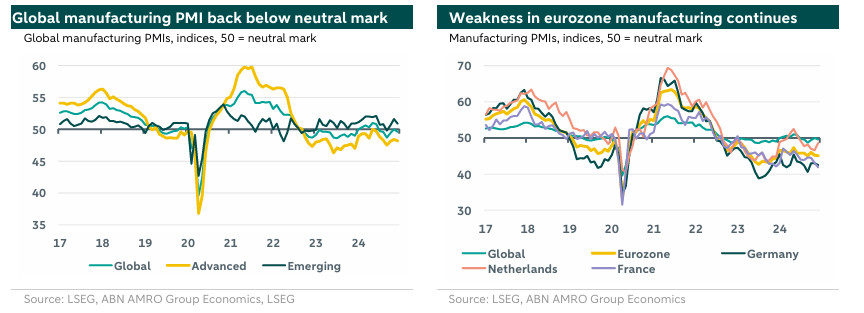

Global manufacturing PMI drops back below neutral mark

After having risen by around 1.5 points in October and November, the global manufacturing PMI ended 2024 on a bit weaker note. The index dropped back to 49.6 in December, just below the neutral mark (50) separating expansion from contraction. Looking back at the whole of 2024, the global manufacturing PMI moved in a quite narrow range around the neutral mark. That was broadly in line with our assumption at the start of last year that global industry would at best bottom out in 2024 compared to a weak 2023, but would fail to show a convincing recovery. Looking forward, our macro outlook for 2025 assumes headwinds from a US trade tariff shock to drive a slowdown in global GDP and (goods) trade in the course of 2025 and in 2026, which is likely to form a drag on global industry as well. Still, frontloading ahead of these (assumed) tariffs is expected to initially boost global trade in the first half of this year, and this would typically create a short-term tailwind for global manufacturing as well (see our see our Global Outlook for 2025, The year of the tariff.

Weakness broad-based; France and Germany weak spots in eurozone manufacturing

In terms of geography, the deterioration in global manufacturing PMIs shown in December was broad-based, with the divergence between relative strength in emerging markets (EMs, in expansion territory) and relative weakness in developed markets (DMs, in contraction territory) continuing:

After having risen to a five-month high in November, the aggregate EM index fell back by 0.7 points in December, to 50.9. This was led by China’s Caixin manufacturing PMI, which is included in the EM aggregate and has been quite volatile in recent months (see our comments on China’s December PMIs here). China’s alternative ‘official’ index published by NBS also dropped, but only marginally. Note that China’s two manufacturing PMIs remain in expansion territory, unlike those of their key DM peers.

Meanwhile, the aggregate index for DMs dropped slightly to 48.2 (November: 48.4), remaining in contraction territory. The weakness is broad-based, with the indicators for the US, the eurozone, Japan and the UK all still below the neutral mark. The eurozone remains a negative outlier, with the eurozone manufacturing PMI dropping slightly to a three-month low of 45.1. This is driven by weakness in both Germany (42.5) and France (41.9, the lowest reading since the initial Covid-19 shock in early 2020). By contrast, the index for the Netherlands rose back by two full points to a five-month high of 48.6, although remaining in contraction territory (see our comment on the Dutch manufacturing PMI here).

Supply weakened more than demand in December

Looking more closely at the global manufacturing PMI’s subindices, the deterioration in global manufacturing was broad based, with the components for output, domestic orders and export orders all coming down compared to November. Whereas the demand side has been generally weaker than the supply side for quite a long time, in December the global output component (supply side) dropped sharper than the domestic and export components (demand side). That drop was led by Caixin’s output component for China, although this sub-index stayed in expansion territory in December and has been quite volatile over the past months. These developments are also visible in our global supply bottlenecks index, for which an excess supply/demand metric (more specifically: output in EMs versus demand in DMs) is one of the key components, next to other measures such as delivery times and backlogs in global industry, or shipping tariffs. Although our index remained in “excess supply” territory in December, it has moved a bit towards the neutral mark, driven mainly by this excess supply/demand metric.

Input price component up again, but still well below previous peaks

While the ongoing global excess supply conditions help keep a lid on cost push price pressures stemming from global manufacturing, the global PMI component for input prices is gradually rising again in recent months – reaching a four-month high of 54.4 in December (November: 53.9). By contrast, the output price component dropped back to a nine-month low of 51.3, suggesting that producers are not (yet) passing through higher input costs to their offtakers. We should add that both the components for input and output prices remain well below peaks seen during the pandemic episode of abundant supply bottlenecks in 2021-2022, and also below the 2024 peak seen in June.

Rising spot container tariffs between China and US signal trade frontloading

We already mentioned before (see here) that in case of heavy trade frontloading regarding US imports in anticipation of higher US import tariffs, we could see short-term pressures on industrial goods’ prices stemming from temporary capacity issues – at least initially, before the demand effects from the trade tariff shock start to dominate. In mid-2018, when the US started to implement China tariffs, the global components for input/output prices only showed a brief and modest uptick (not necessarily one-on-one related to these tariffs), but we expect a much bigger and broader tariff shock this time. Interesting observation in this respect comes from spot container tariffs. Freight rates for shipping between Shanghai and Los Angeles/New York have risen by around 45% on average since mid-December. This may well be an early sign of trade frontloading, which could turn out to be a short-term help for global manufacturing.