Fed Watch - June rate cut no longer looks plausible

We now expect the Fed to start cutting rates in July (previously June), with a pause in September, and a total of three 25bp cuts expected in 2024 (previously five). Rates are expected to fall to the estimated neutral level of 3% by November 2025. We do not think the Fed is wedded to changing policy in quarterly projection months, and nor do we think the election timing is a significant factor. Our ECB view is unchanged; it would take a much sharper move in the euro to affect ECB cuts. Rates forecast update: The change in Fed view raises our near-term short-end yield forecasts for the US, but long-end yield forecasts are much less impacted. Our euro rates forecasts are mostly unchanged.

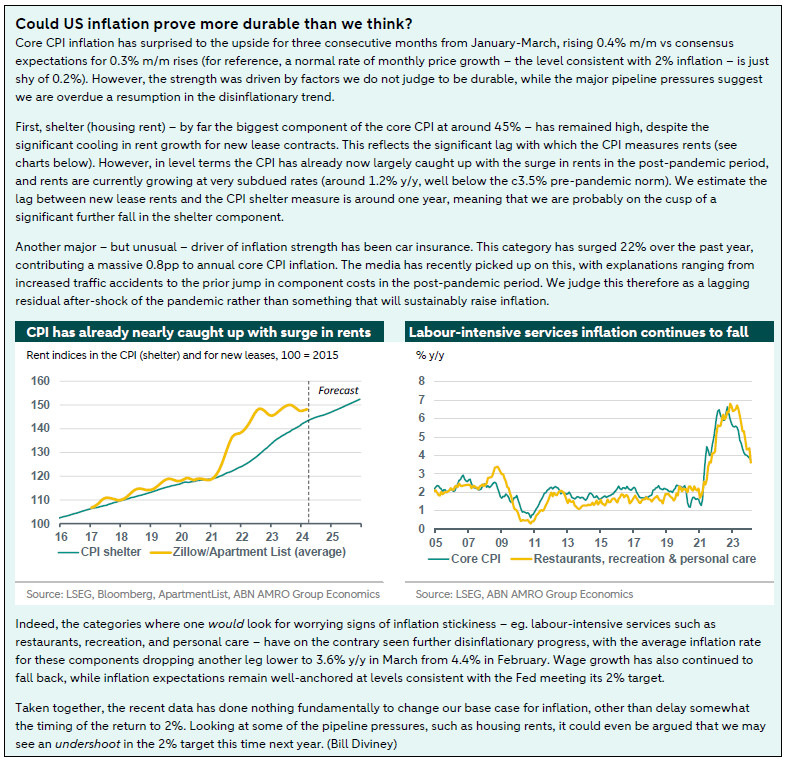

Following Wednesday’s upside CPI inflation surprise (see Box) – the third in a row – we are changing our call for the start of rate cuts for the Fed to July, from June previously. We also now expect the Fed to proceed with rate cuts at a more gradual pace initially – with a pause expected at the September meeting – as the central bank waits to gain confidence that inflation really is durably back at the 2% target. This means that we now expect three rate cuts in 2024, down from five previously. We continue to expect the upper bound of the fed funds rate to settle at 3%, though we now expect that level to be reached one quarter later (in November 2025 instead of July).

The reasons for the change are twofold. First, although we see nothing in the inflation data – nor in the pipeline pressures – to suggest the recent high readings will be sustained, we think it will be difficult for the FOMC to come to a consensus on rate cuts by the June meeting, as they will likely require a number of low or benign inflation readings to be confident the US is back on track to 2% inflation. By June, there will only be two further inflation reports, which will probably be insufficient.

Second, the strength in economic activity (see ) reduces the urgency to cut rates. While the economy has slowed to a more trend-like pace in 2024 so far, there is little sign of weakness in the economy. As such, we think the Committee can probably afford to be patient in order to confirm that disinflation has resumed.

Why not start cutting in September? Why the pause?

Pipeline indicators for inflation, such as weak growth in new housing lease rents, and benign wage growth, suggest that we are overdue some downside surprises to the inflation data. In Q4 last year, inflation persistently surprised to the downside. Assuming we see more benign readings for inflation over the coming months, we think the Fed will want to get some easing ‘in the bag’, considering the lags with which monetary policy works. This therefore favours a first cut in July. However, given the volatility we have seen in inflation, we also think it is reasonable that the Fed proceeds more carefully with rate cuts initially. While the precise timing of any pause will depend highly on the dataflow at that time, we judge that September would be a reasonable point to hold policy and take stock of developments before proceeding further. By November, inflation should be more durably back at the Fed’s 2% target, which should give the Committee the confidence to cut at consecutive meetings until a more neutral level of interest rates is reached in late 2025.

Aren’t projections months more important?

The Committee updates its economic projections on a quarterly basis – in March, June, September and December. Historically, these months have held greater weight for policy decisions, also because these used to be the only meetings accompanied by a press conference. However, under Chair Powell’s tenure, a press conference now accompanies every meeting, and NY Fed president Williams has said “rate moves won’t need to be timed to meetings at which officials update their quarterly economic forecasts.”

Is there a precedent for rate cut cycle pauses?

When rate cuts start, they usually come at consecutive meetings, so it would be historically unusual for the Fed to pause after starting to cut rates. However, we think the current circumstances – of reduced confidence in forecasting and heightened data-dependence – makes a pause more likely than in the past. More recently, the Fed paused when it was coming to the end of its hiking cycle, at the June FOMC meeting last year.

Does the election make any difference?

The US presidential election takes place on Tuesday 5 November, while the November FOMC meeting concludes on Thursday 7 November (it is unusual for a FOMC meeting to conclude on a Thursday; this likely is due to the election timing). We have seen some suggestion that the Fed would likely not cut rates in September and perhaps even November, to avoid being seen to support a particular candidate in the election. We do not put a great deal of weight on this, although we happen to think that the likely evolution of the data will support a July start to rate cuts and a September pause. While the November meeting is close to the election, crucially it takes place after the vote – meaning that any move is unlikely to be seen as politically motivated, regardless of the outcome. (Bill Diviney)

What does the changed Fed view mean for the ECB?

We are keeping our ECB base case, of a 25bp rate cut at each meeting from June onwards, unchanged. As President Christine Lagarde made clear at the press conference of the April Governing Council meeting (see ) the ECB is data dependent ‘not Fed dependent’. Of course this does not mean what the central bank of the largest economy of the world has no bearing on the ECB, but rather it depends on the specific spillover effects. These can be put in three categories (1) the currency impact (2) the impact on broader financial conditions (3) the impact on Europe’s export markets – especially the US. We do not see large effects on any of these three areas, while they are also offsetting, with the possibility of a weaker euro having to be weighed against the possibility of tighter financial conditions. We think the EUR/USD will largely remain in the 1.05-1.10 range it has been in (see our upcoming FX weekly for more on this) given that the expected relative repricing of interest rate expectations (relative to our respective base case for the Fed vs ECB) will not be large due to the change in our Fed view.It would take a much sharper decline in the euro than we expect to trigger a change in the ECB's trajectory.

At the same time, the case for an ECB rate cut cycle remains clear. We take the view that interest rates are currently deeply in restrictive territory. Estimates of the neutral rate are half or less than the current level of the deposit rate. Given that the eurozone economy has been stagnating for more than a year, the only justification for restrictive monetary policy has been above-target inflation. However, the inflation picture is changing fast. Even assuming 125bp of rate cuts this year, monetary policy would still be restrictive at the end of 2024. (Nick Kounis)

What does the changed Fed view mean for bond yields?

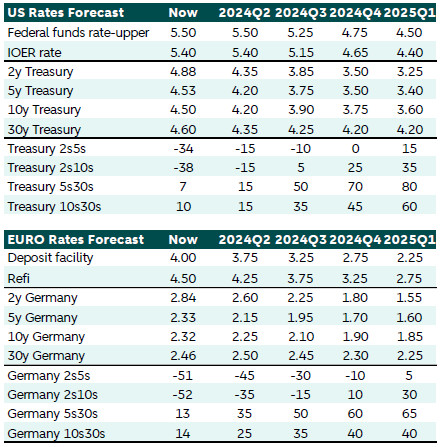

Following the changes in our Fed outlook, we revised our US Treasury yield forecasts higher. As shown in the table below, the main changes were skewed to the front-end of the yield curve (the 2y and 5y bond yields) as those rates are more anchored to monetary policy than longer bond maturities. The revision reflects that we now have 50bp less Fed rate cuts by the end of this year than previously. Still, we judge the pricing out of rate cuts by the market is overdone even on the basis of our new scenario. Markets currently price in even fewer rate cuts than in the Fed dot plot (which signals 3 cuts versus 1.5 by the market currently) as well as a much higher terminal rate at 4.2% against 3%-3.25% in the Dot plot. Thus, despite our Fed revision, we remain confident that outright yields will fall once we approach the rate cut cycle in the summer as market should adjust its policy rate expectations closer to true neutral rate.

Overall, the changes only marginally affect our European rates projections (see table below). The main effect is for short-term rates to fall somewhat less than previously expected. In the end, the timing of the Fed and ECB rate cuts is only one month apart and we still expect a significant repricing of rate cuts by the market for this year in the coming months on both sides of the Atlantic. As such, we think the direction of bond yields over coming months will be downwards. (Sonia Renoult)