ESG Strategist – Sustainability-linked bond market at a crossroads

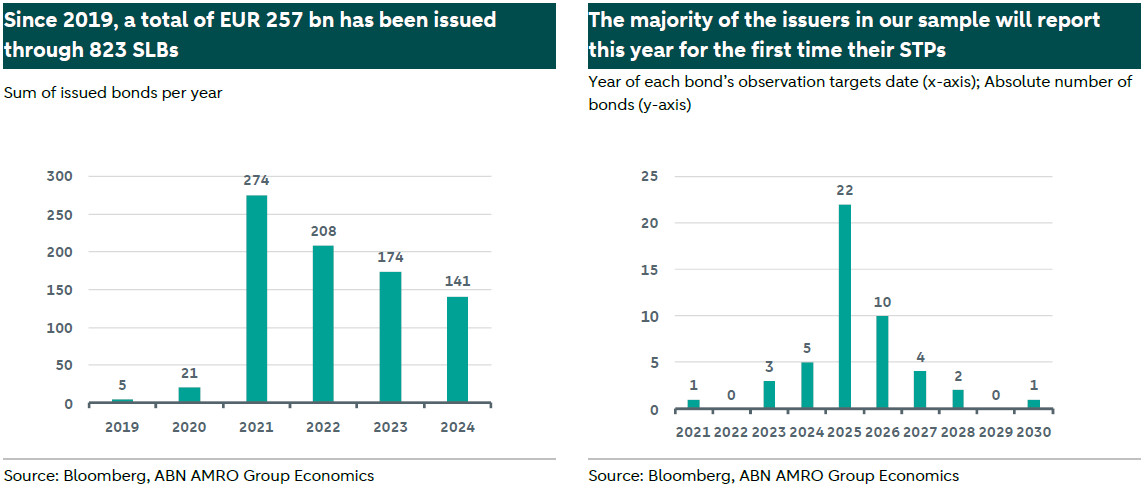

Back in September 2019, the Italian utility company Enel issued what would be the first ever sustainability-linked bond (SLB). In total, since 2019, EUR 257 billion was issued by 400 issuers through 823 SLBs. The SLB market reached a peak in 2021, fuelled by the entry of prominent issuers, and has been steadily declining since 2022, due to unfavourable economic conditions, rising interest rates, and heightened concerns around the credibility of the SLB market have hampered volumes since. Last year, SLBs accounted for 5% of all ESG bonds listed worldwide (i.e., green, social, sustainability, and sustainability-linked bonds).

In this note we explore the trends and the challenges of investment grade corporates and sovereigns issuing SLBs

Since 2019, EUR 257 billion of SLBs were issued by 400 issuers

However, SLB issuance reached a peak in 2021, and it has been steadily declining due to unfavourable economic conditions and heightened concerns around the credibility of the SLB market

2025 is the year expected to set new records for SLBs in terms of targets due

The lack of common standards might be jeopardizing the development and growth of the SLB market

Each SLB issued has an observation date, which is the date where the targets are expected to be tested. 2025 is anticipated to set new records for SLBs in terms of targets due. As such, we aim to present an overview of the current state of the SLB market in this note. We focus on active euro-denominated sustainability-linked bonds issued by investment grade corporates and sovereigns,. This leaves us with 48 SLBs analysed. Above, we display the observation target dates for the bonds analysed in this note. Most bonds in our sample, similar to the entire SLB universe, will report on whether their targets were achieved or not for the first time this year.

Before proceeding with our analysis, it is important to mention that legal documentation is publicly accessible for most of our sample, though it is dispersed across bond frameworks, press releases, or websites. While this situation is common for all ESG bonds, it poses a greater challenge for SLBs due to their unique financial characteristics and target systems. Therefore, we would encourage issuers to make final terms publicly available and provide clear transparency regarding which SLBs are linked to specific targets, including the detailed structural mechanisms established. For instance, issuers could publish a comprehensive table on their websites to ensure accessibility and clarity.

We begin by offering an overview of the SLB market and conclude with some challenges and recommendations to enhance the market's strength and guide the use of this financial instrument.

Trends in the SLB market

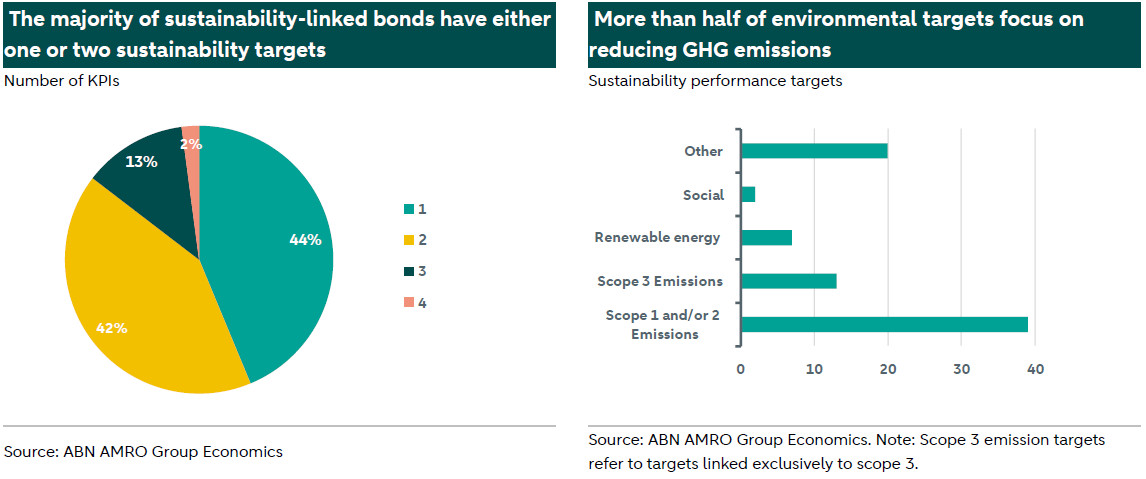

SLBs tie the financing costs to specific sustainability Key Performance Indicators (KPIs). Unlike green or social bonds, which concentrate on funding projects with distinct environmental or social advantages, SLBs are distinct due to their performance-based nature. That is, SLBs’ use of proceeds target general corporate purposes instead of ESG projects. The bond's financial or structural features, such as the interest rate, are directly tied to the issuer's success in meeting predetermined sustainability goals. Below, we plot both the number of KPIs observed per bond and the focus areas of these KPIs.

Typically, the KPIs outlined in an issuer's SLB framework do not completely align with the KPIs specified for each individual bond. For example, an issuer might decide to allocate the bond's proceeds towards just one KPI, while the framework includes several. As a result, each bond generally focuses on fewer KPIs, often just one or two, in comparison to what is included in the framework. Moreover, these targets are usually environmental targets with a quantitative target, such as a reduction in waste by a specified ton amount or a reduction in CO2 emissions. For instance, more than half of the non-financial companies in our sample have set targets aiming at Scope 1 and/or 2 emissions’ reduction. Scope 3 emissions are also targeted, although by considerably less companies. That is even though scope 3 emissions tend to be the largest amount of emissions for most companies (especially utilities companies, which are some of the largest issuers of SLBs).

As previously highlighted, several companies have set their targets to be due in 2025. The Climate Bonds Initiative conducted an last year that revealed a market characterized by diverse KPI performance relative to these targets. This variability is neither surprising nor negative, considering the market's infant stage. Their findings indicate that while several targets have been achieved, the most common result is that many KPIs are not on track. This situation partly stems from adverse external factors over recent years that are beyond the control of individual entities, such as Enel, which attributes all KPIs being off-track to geopolitical issues such as the Ukraine conflict.

Additionally, the Climate Bonds Initiative encountered a similar challenge as we did in conducting this analysis: the scarcity of publicly available post-issuance reporting. Furthermore, the disclosed information often lacks clarity on whether a company is on track to meet its targets, making it difficult for readers to impartially assess how the data compares to the targets. Consequently, one of our recommendations moving forward is for issuers to regularly disclose public data regarding the KPIs set under the SLB and explicitly clarify the impact of these numbers on the baseline and targets. Additionally, issuers should ensure that consistent information is available across their website, entity-level reports, and SLB documents, facilitating easy access to SLB-related information for investors.

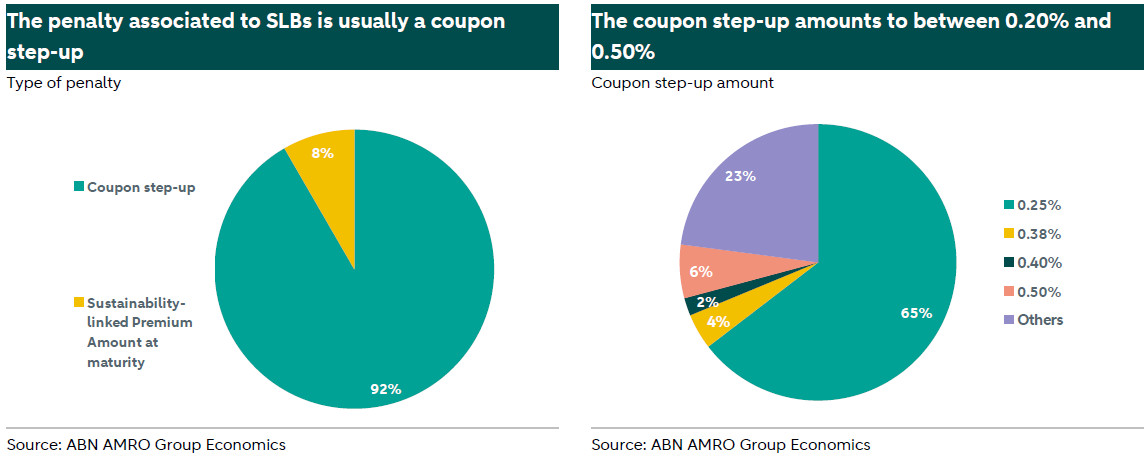

As previously noted, SLBs are distinctive due to their performance-based nature, imposing a penalty and/or reward if a company fails to meet the targets established at issuance. Regarding penalties, most companies have chosen a coupon step-up for each Sustainability Performance Target (SPT). This means that if a company does not achieve one or all of its targets, the coupon paid after the observation target date will increase by a predetermined amount. This is typically 0.25%, but it may range between 0.20% and 0.50%. However, some issuers, such as Enel and Pandora A/S, have opted to pay a sustainability-linked premium amount at maturity instead of a coupon step-up.

Nevertheless, it is important to note that the prevalent use of a 25 basis points (bps) penalty lacks a clear rationale, a conclusion also observed across the market (see ). The OECD suggests that the tendency towards a 25bps penalty might simply reflect the market's relative immaturity. Additionally, indicates that the savings from the “greenium” (or SLB premium, meaning SLBs benefit from more favourable pricing conditions compared to similar non-SLB bonds, due to the additional value investors attribute to the environmental benefits linked to SLBs proceeds) frequently exceed the penalties issuers face for not achieving targets. Consequently, some issuers might be exploiting the system to benefit from favourable pricing while ultimately avoiding significant costs.

Conclusion: growing support for SLBs, yet room for improvement

In a particularly noteworthy development, the European Central Bank (ECB) began accepting Sustainability-Linked Bonds (SLBs) as collateral starting January 2021 (see ). The ECB provides specific criteria for the SLBs it accepts, requiring them to be tied to targets addressing environmental objectives outlined in the European Union (EU) Taxonomy or Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) focused on climate change or environmental degradation. This demonstrates the increasingly important role of central banks in supporting innovation in sustainable finance and sent a clear message of support for SLBs to the market. Despite this backing, the SLB market has not expanded significantly, accounting for only 5% of the entire sustainable finance market last year. That is hardly surprising in an emerging market with limited voluntary guidance and no mandatory regulations.

In response, on December 2024, the European Commission released the EU Green Bond Standard along with optional disclosure templates for SLBs in the EU. The Commission recognizes that the absence of standardized disclosure templates at the Union level makes it challenging for investors to easily and reliably access necessary information, and to compare and aggregate data on these bonds. Specifically, the lack of a unified methodology for issuers’ reporting leads to administrative challenges and uncertainty for bond investors. Consequently, as stated by the Commission, to "facilitate comparison and address greenwashing, optional sustainability disclosure templates should be provided […] for sustainability-linked bonds." Additionally, the Commission plans to publish a report by 21 December 2026 to assess the need for regulating sustainability-linked bonds.

These voluntary templates are expected to support the development and expansion of the SLBs market, although we advocate for the implementation of mandatory standards that issuers can adhere to and comply with. Such minimum standards should ensure the quality and credibility needed by investors, paving the way for a future where all financing is linked to sustainability performance.