ESG Strategist - Are credit rating agencies overlooking climate risks?

Climate risks are mounting across the world and Europe is not immune to this global development. The devastating floods in Valencia and the wildfires in Portugal are just recent examples of a phenomena that is expected to become increasingly frequent. As it was noted in our previous research (see [1]), acute physical risks – such as floods, or wildfires – can result in significant direct economic damages, such as the loss of buildings, livestock, natural resources and infrastructure, which in most instances is only partly insured. Moreover, climate-related disasters can also have longer-term impact on economic growth. These can ultimately affect the ability of a country to repay its debt, such that climate-related risks should be – if not already - considered by credit rating agencies. Hence, in this note, we aim to dive deeper into sovereign ratings, in order to understand whether climate-related indicators are accounted for by rating agencies when assessing country risks. We solely focus on climate-related indicators, given that past research has proven that the social and governance pillars (the other components within the E, S and G) remain the biggest drivers of sovereign risk premia (the exception being low-income countries where some environmental variables stand at the forefront - see [2]). This note is structured as follows: below we discuss the data and the methodology used, followed by our interpretation of results. Finally, we finish the note by offering conclusions.

Acute physical risks can cause substantial economic damage and have long-term effects on economic growth, potentially impacting a country’s ability to repay its debt

Therefore, credit rating agencies should incorporate climate-related risks into their evaluations

In this note, we investigate whether Moody’s has considered climate-related variables in their country assessments from 2015 to 2021

We use as control variables lagged macroeconomic variables, European Commission forecasts, and social- and governance-related variables in order to isolate the climate pillar

Our findings suggest that rating agencies take freshwater usage and the share of protected land into their rating assessments…

… but that does not seem to be the case for greenhouse gas emissions, highlighted by their lack of significance in our model

Our results are nevertheless limited by the availability of data and the restricted time frame of the study

Data & Methodology

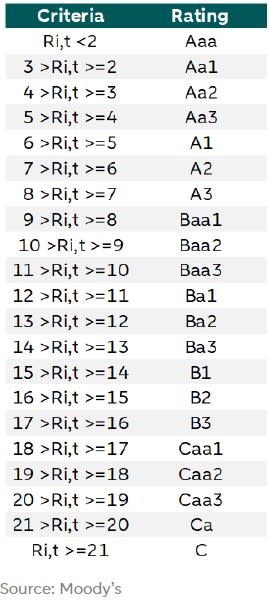

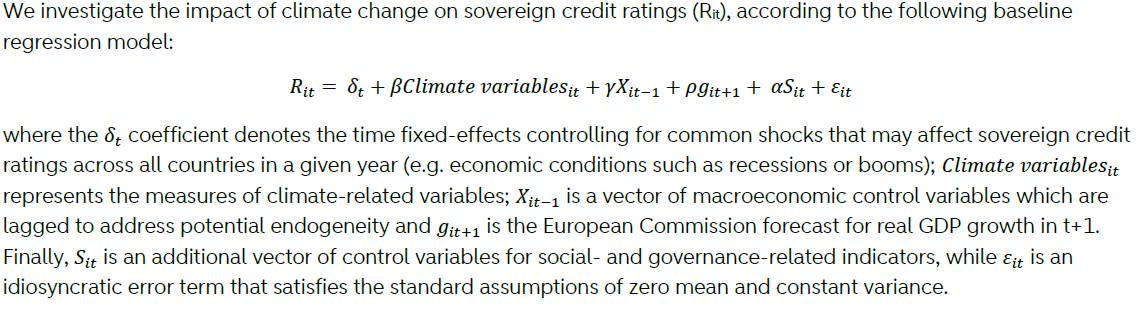

We use several data sources to construct a panel dataset of annual observations covering the 27 European Union (EU) countries over the period 2015-2022. The choice of the time-frame regards the availability of data, given that climate-related data is scarce before 2015. 2015 is also the year that the Paris Agreement was signed, and several research sources have shown that climate-related data is neither trustworthy nor abundant before that year. The data on sovereign credit ratings is drawn from Moody’s. We use it to construct our dependent variable, Rit (correct writing in table below), which indicates a country’s credit rating at the end of each calendar year. The variable Rit is then assigned a rating if the predicted value by the model falls between a range of pre-determined values. This is demonstrated in the table below.

Since rating assignments typically rely on non-linear models and probabilities, we model Rit (correct writing in table above) based on the odds of the issuer being classified into a specific category. Therefore, Rit will represent the log(odds), where the odds reflect the probability of the issuer receiving a higher or lower rating, determined by factors such as its macroeconomic performance, political stability, and others (details discussed further below).

The main explanatory variables of interest are greenhouse gas emissions per capita (tonnes of CO2 equivalents per person), freshwater usage as a share of total available water, and protected land area as a share of total land. Moreover, we include the following conventional determinants of sovereign credit ratings as control variables (please revert to the appendix for more information on this): real GDP per capita, real GDP growth, inflation rate, unemployment rate, and the ratio of government debt to GDP. We also include the forecasts of the European Commission for the real GDP growth rate - which are usually not considered by the literature. Furthermore, and as mentioned previously, because we want to isolate climate-related variables, we use control variables that capture both social and governance issues, such as the share of the population, that has an age between 15 and 64 years old and less than primary education, women’s employment rate and political stability. We rely on data from the European Commission, the Eurostat, the European Central Bank (ECB), the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank’s World Development Indicators (WDI) database.

There are two econometric approaches commonly used in the literature. The first approach is a linear regression method that estimates a numerical representation of credit ratings, which also allows for panel data applications. The second approach is based on an ordered response model that uses credit ratings as a qualitative ordinal measure. In this note, we use an ordered response model (probit) estimated using the maximum likelihood approach, given that the OLS approach is better to capture large differences in credit ratings, but mis-estimates small differences – as the ones observed across EU countries.

Results

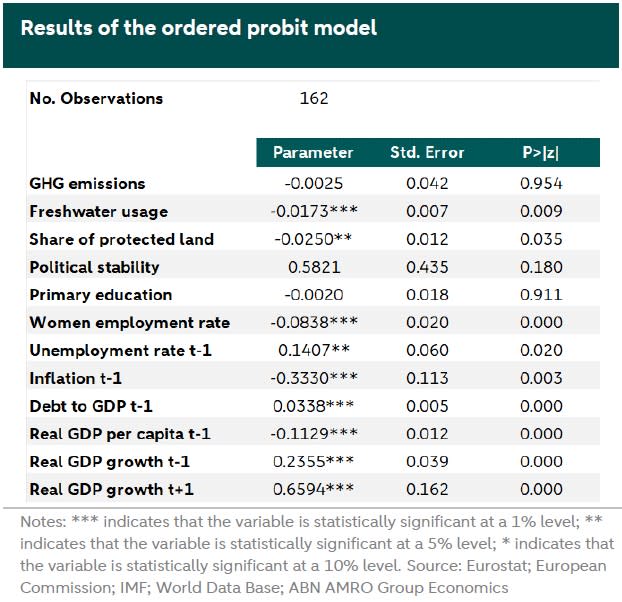

We note that there is no multicollinearity present in this model. Then, we proceed to assess the overall significance of the model. Furthermore, we assess the overall significance of the model using a chi-square statistic given that we are using an ordered probit model. According to the results, the model is overall significant at the 1% level.

We begin by examining our key variables of interest (the climate indicators). Our findings indicate that two out of the three variables are statistically significant at the 5% level, namely freshwater usage and the share of protected land relative to total land area. Interestingly, the sign of the coefficient for the freshwater usage variable contradicts our expectations. Specifically, the results suggest that increased freshwater usage correlates with a better sovereign rating. This may be attributed to the development level of a country, as developed nations typically consume more water due to agricultural, industrial, and household needs. Hence, a higher freshwater usage might indicate a more advanced (and active) economy, which has a positive impact in the sovereign’s credit rating. However, high freshwater usage also leaves these countries vulnerable to potential water stress or future shortages due to high water dependency. Consequently, would rating agencies start to consider freshwater usage as an indicator of exposure to climate risks, countries currently heavily reliant on water may be exposed to potential impacts in their credit ratings.

Regarding the share of protected land, the coefficient sign from our model aligns with our expectations. That is, the greater the share of protected land, the better the sovereign rating. This finding is consistent with recent EU legislation, which mandates that countries protect at least 30% of their total land by 2030. As such, countries that have a larger share of protected areas, are less susceptible to biodiversity-related risks and less likely to face penalties from the European Commission in the future. Nevertheless, given how recent this legislation is, it might not entirely explain why this variable is statistically significant. One possible reason for the significance could be related to the governance of a country - the decision to protect land reflects governmental priorities and the ability to implement and enforce policies, which are important aspects of governance that rating agencies consider.

Regarding greenhouse gas emissions (GHG emissions), the results suggest that higher emissions are associated with better ratings. However, since this variable is not statistically significant, it appears that rating agencies may not be factoring emissions at all into their country assessments. If this variable were to be significant, it would imply that rating agencies are not penalizing countries that fail to reduce their GHG emissions. On the contrary, they are estimating lower default risks for countries with higher emissions (likely driven by the fact that higher GHG emissions are associated with a more developed industry and economy as a whole). However, as countries continue to emit, both their physical and transition risks increase, making them more vulnerable to future shocks and potentially compromising their ability to repay debts.

Turning to our control variables, most are consistent with existing literature and are statistically significant at the 5% level. For example, higher real GDP per capita is associated with better sovereign ratings, while higher unemployment rates and debt-to-GDP ratios correlate with poorer ratings. Real GDP growth is also statistically significant, however, the sign of its coefficient may seem counterintuitive. According to the table, countries with higher rates of GDP growth are correlated with poorer ratings. This is actually in line with previous research (see ), which showed that less developed countries often exhibit higher-than-average GDP growth rates, but receive lower ratings due to political instability, high levels of inflation, among others. Even though all countries in the EU are considered developed countries, eastern European countries tend to be less economically developed than its peers (e.g. Germany, France, Netherlands). Moreover, those countries also tend to register higher-than-average growth rates, given that their starting point is also lower. As such, GDP growth rates are not per se a reliable indicator of a country’s debt repayment ability, having to be considered in conjunction with other variables.

A similar reasoning applies to the GDP growth rate forecast, as reported by the European Commission. According to the table, this variable – which was not often included in previous literature – is also statistically significant at the 1% level, and in the same direction as the lagged GDP growth rate.

Inflation, meanwhile, is statistically significant, although its coefficient’s sign does not align with the literature or our expectations. High inflation typically undermines economic stability, making it difficult for businesses and consumers to plan for the future, which rating agencies may view negatively when assessing creditworthiness. Therefore, we would expect that higher inflation levels, would be correlated with poorer ratings. However, according to the results above, higher inflation tends to result in better sovereign ratings. A possible explanation for this anomaly could be the specific period under review. From 2015 to 2021, inflation remained below the European Central Bank's target of 2%, indicating a sub-optimal economic environment with sluggish inflation and growth, particularly in certain European countries. Therefore, during this time, higher inflation may have been seen as beneficial, suggesting a return to more normal economic growth. As a result, countries experiencing above-average inflation rates were perceived as healthier.

Lastly, concerning our social and governance-related variables, only one of the three variables is statistically significant – contrary to previous research findings (see ). Given our limited sample size, these results should be interpreted cautiously. Nevertheless, as expected, countries with a lower share of unemployed women tend to have better sovereign ratings, as this indicates a robust labour market.

Recommendations and conclusion

While some results, such as the statistical significance of freshwater usage and the share of protected land, are encouraging, there is still significant room for improvement. Rating agencies need to recognize the critical need to account for the risks climate change poses to economic growth and debt sustainability, making it essential to include relevant variables when conducting rating assessments. One of the most significant of these is a country’s greenhouse gas emissions.

Nevertheless, our analysis has limitations, particularly the short and narrow time frame, which may introduce bias or obscure results. As rating agencies make continuous progress in addressing climate issues, a study covering a longer and more recent period might offer different perspectives and more positive findings. Additionally, as corporations and countries enhance the availability and quality of climate-related data, this will further aid the efforts of rating agencies, researchers, governments, and, ultimately, investors.

Appendix

Real GDP per capita: the greater the potential tax base of the borrowing country, the greater the ability of a government to repay debt. This variable can also serve as a proxy for the level of political stability and other important factors;

Real GDP growth: a relatively high rate of economic growth suggests that a country’s existing debt burden will become easier to service over time;

Inflation rate: a high rate of inflation points to structural problems in the government’s finances. When a government appears unable or unwilling to pay for current budgetary expenses through taxes or debt issuance, it must resort to inflationary money finance. Public dissatisfaction with inflation may in turn lead to political instability;

Unemployment: high unemployment typically indicates underutilization of labour resources, which can lead to lower overall economic growth. A stagnant or contracting economy can reduce government revenues from taxes, making it more difficult for the government to meet its debt obligations;

Government debt to GDP ratio: a high debt-to-GDP ratio suggests that a country has a large amount of debt relative to its economic output. This can raise concerns about the country’s ability to meet its debt obligations, increasing the perceived risk of default. Moreover, as debt levels increase, so do the interest costs associated with servicing that debt. A high debt-to-GDP ratio might indicate that a significant portion of government revenue is being used to pay interest, leaving less available for other essential services and investments. This can be a negative factor in credit assessments;

Primary education: a high proportion of people with less than primary education can limit the competitiveness of a country’s labour market. Lower education attainment often translates to a workforce with fewer skills, which can reduce productivity and hinder economic growth. This can, in turn, impact government revenues and fiscal stability;

Women’s employment rate: when women face higher unemployment rates, it can signify barriers to entry in the labour market, such as the lack of access to affordable childcare, discrimination, or inadequate maternity leave policies. Addressing these barriers can enhance economic output;

Political Stability: political stability ensures continuity and predictability in government policies, which is crucial for economic planning and investor confidence. Stable political environments enable governments to implement long-term economic strategies, making it easier to manage public finances and debt.