ESG Economist - The role and effectiveness of Dutch transition subsidies

The energy transition is essential in achieving emission reductions and climate targets in time. For renewable investments a wide range of subsidies are available. In this publication we zoom into subsidies for renewable energy production and climate transition (SCE/SDE) offered by the Dutch government to enhance clean projects matching the transition agenda. In the coming years, funds originating from the subsidy schemes are expected to increase, affecting Dutch government finances. Dutch subsidy schemes are appropriate and popular to stimulate and incentivize corresponding clean investments. However, due to challenges around cost of financing, labour market tightness, nitrogen limits, and the electricity grid, we emphasize the need for a dynamic, timely, and proactive subsidy scheme. Coordinating the different components of the transition process is essential for keeping the scheme up to date to reflect the impacts of any emerging obstacles. Subsidy schemes for clean technologies should align with other climate policies, such as carbon pricing, to achieve a timely, orderly, and efficient transition.

Introduction

The energy transition is essential in achieving emission reductions and climate targets in time. The transition entails a switch towards low carbon technologies such as renewables, sustainable fuels, electrification, efficiency improvements, or the use of carbon capture. Such a switch needs to happen in a timely manner if emission targets are to be met. However, even with the readiness of the needed technologies, the deployment is still not up to speed. A main challenge comes from reluctance, which is driven by the high associated costs and lower competitiveness of low carbon technologies in comparison to the fossil fuel abased alternatives.

Access to finance is another obstacle for low carbon investments as these investments are capital intensive, long-term, and usually associated with uncertainties increasing their risk profile which does not match the risk appetite of most private investors. The wide difference in fixed and operating costs between clean and fossil-based technologies requires an intervention to ameliorate the business case of low carbon technologies.

A main instrument that gives clean technologies a comparative advantage is carbon pricing, which increases the cost of high emission technologies and improves the business case for low carbon ones. However, for some transition needed technologies, carbon price is not enough and leaving the transition to market dynamics will take too much time. Thus, additional intervention that complements carbon pricing is necessary to achieve a smooth and timely transition. Subsidies, such as CAPEX and OPEX subsidies, are one way to complement carbon pricing to enhance the adoption of different clean technologies.

In this article, we zoom in on subsidies for renewable energy production and climate transition (SCE/SDE) offered by the Dutch government to enhance clean projects matching the transition agenda. First, we review the background of these subsidies and their targets. We move afterwards to their status, effectiveness, practical implications, and the link to the Dutch government finances. Finally, we conclude with suggestions and recommendations for more effective schemes.

An overview of the Dutch low carbon and transition subsidy schemes

In this section, we give an overview the most prominent Dutch subsidy schemes that aim to incentivize investments in low carbon and transition needed technologies.

Money reserved by the government for transition subsidy schemes is mainly financed by the revenues from the auctioning of emission allowances under European Union Emission Trading Scheme (EU-ETS). Higher CO2 price translates into lower subsidy for sustainable projects because those that start such a project have higher savings in CO2 costs. Part of the financing for these projects originates from the Dutch cabinet plan to spend more money on reaching climate goals (). There are different subsidy schemes by the Dutch government. Below we highlight these subsidies, their criteria, and targets. There are three main transition related subsidy schemes offered by the Dutch government, which we explain next.

Subsidy Demonstration Energy Innovation (DEI+)

The subsidy is targeted towards projects at a pilot or demonstration phase. The subsidy is aimed at projects with a focus on one of seven themes (circular economy; energy efficiency; flexibility of energy systems; renewable energy; Carbon Capture, Utilization and Storage (CCUS); local infrastructure; any other measure that reduces CO2 emissions in the built environment, industries or power generation; Houses, buildings, and blocks that do not use gas). The budget available in 2022 was EUR 74.6 million. Depending on the project type and theme, entrepreneurs could receive between 25% and 80% of eligible costs with a maximum between 9 and 15 million per project.

Subsidy scheme for Cooperative Energy Generation (SCE)

This subsidy scheme aims to stimulate the generation of renewable energy from solar, wind, or hydro sources by energy cooperatives and homeowners' associations. It applies to both small and large connections. The scheme was launched in April 2021 with EUR 92 million available for the first round.

The SCE subsidy is an OPEX subsidy that guarantees the profitability of the installation through its lifetime. The subsidy is paid as an amount per kWh produced. For each type of installation, the RVO (Netherlands Enterprise Agency) sets a base amount per kWh that is needed to make the installation profitable. The base amount in the year application is then valid for 15 years. The paid subsidy is the difference between the base amount of the project and the market price for power produced.

Simulation of sustainable energy production and climate transition (SDE++)

This subsidy scheme targets renewable energy generation projects or the implementation of CO2 reduction technologies (CO2 storage/low-CO2 production ()). There is EUR 8 billion available for this scheme under the 2023 round. Moreover, the SDE++ is an OPEX subsidy that aims to subsidize the difference between the market value of produced energy and the cost of renewable energy production, guaranteeing the profitability of such project, where market value is calculated on annual basis and verified for the Netherlands.

The subsidy works as a guarantee; building sustainable energy generation is expensive and has large start-up costs. Owners receive a compensation. When the electricity price is high (like the last year) the subsidy is not paid out as the projects are ‘in the money’ and earning well. If the electricity price declines, there is an operating deficit, and the subsidy is paid out to compensate these low revenues (). For SDE++ subsidies, the grid operator must provide a positive ‘transport indication’, which indicates that transport capacity (for electricity on the grid) is available at that location (TNO, electrolysis as solution for grid congestion)

Other subsidy related developments

In May 2023, the Dutch government announced a new €28.1 billion Climate Package for reducing CO2 emissions (). This package is mainly targeted towards onshore and offshore green hydrogen production, storage, imports, and a pipeline network in the North Sea. The funding is tailored according to the type or production capacity of different projects with a possibility of both CAPEX and OPEX subsidies.

International subsidy schemes

According to the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), global investments in energy transition technologies in 2022, including energy efficiency, reached USD 1.3 trillion. It is an astronomical amount and even proved to be a new record in the level of investments. At first sight, this is very encouraging, of course, but unfortunately much more is needed than this. IRENA thinks the global energy transition will require another USD 150 trillion investment in a variety of low-carbon technologies between 2023 and 2050. This would mean an annual investment of EUR 6.8 trillion globally a year from now. This means that we still have a long way to go.

Investment in specifically renewable energy was also unprecedented, totaling USD 0.5 trillion in 2022. But even this amount falls short of achieving the set climate targets, in this case IRENA's 1.5 degrees Celsius scenario in the World Energy Transition Outlook 2023 (). The 2022 amount represents less than a third of the average investment needed each year, according to IRENA. To accelerate this in continental Europe, many subsidy schemes are available. Their goal is to not only encourage renewable energy investments going forward, but also keep the investment accessible for companies.

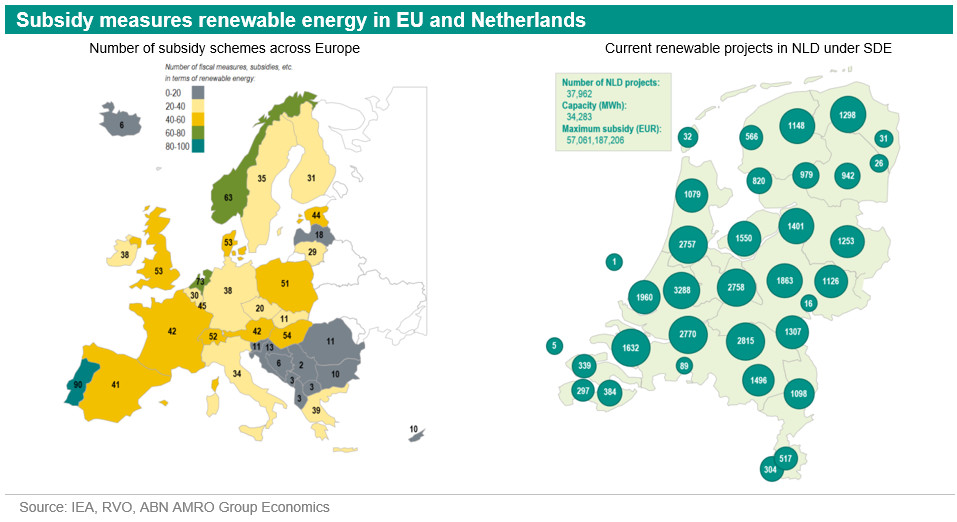

Below we show how many renewable subsidy opportunities there are currently per country in Europe. Leading with a number of 90 renewable energy subsidy schemes in Europe is Portugal. The Netherlands is second in this perspective with 73 subsidy schemes, closely followed by Norway. From the graph it also becomes clear that there are plenty of options spread across Europe to encourage renewable energy financing.

The availability of these subsidy schemes for renewable energy development has proved successful in almost all countries in Europe. The growth in the number of installations and installed capacity in solar PV, onshore and offshore wind has been substantial in recent years partly due to the subsidies. It made investments in renewable energy accessible to a wide range of companies. This has allowed especially SMEs, for example, to make relatively large use of the scheme, for whom such an investment is often financially challenging.

In the Netherlands, the renewable energy subsidy scheme (SDE++) is very popular. This is evident not only from the strong growth in the number of projects spread across the Netherlands, but also from the strong growth in the number of applications to the SDE++ subsidy. For instance, outgoing minister Jetten (Climate and Energy) announced recently that almost two thousand SDE++ applications have been made for a total of EUR 16.3bn in 2023. This appears to be more than double the amount of renewable subsidy available for this purpose (EUR 8bn).

It shows that subsidy schemes for climate financing from the government will continue to play an important role in the coming years. Not only to boost capacity and installed capacity, but also to serve as bridging the financing gap for companies with less financial capacities. It is probably the most ideal way to further scale up investment in renewable energy in the coming years.

What have the subsidies generated so far and what is still in the pipeline?

In this section we highlight the progress of the SCE and SDE++. We do this by using data provided by the RVO (the Netherlands Enterprise Agency), which allows for illustrating the power these projects have generated so far, and what is still in the pipeline.

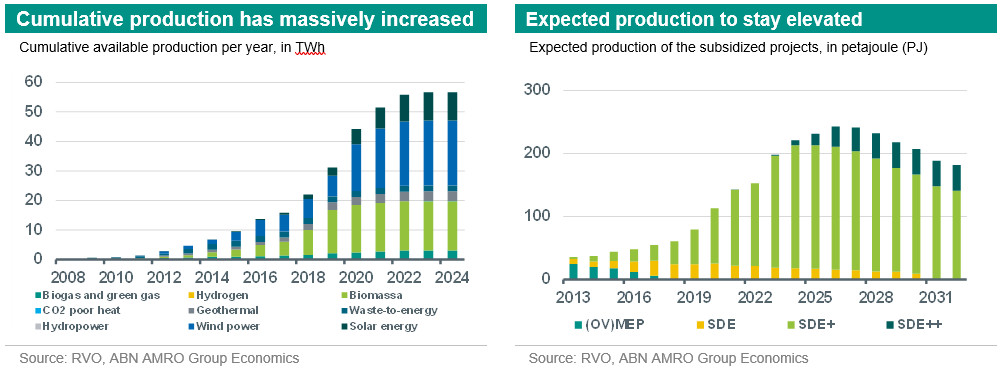

From the application rounds where the subsidy scheme was open, on average 75% was realized or is still in development, and the rest has not been realized and the subsidy has been withdrawn (). Reasons for not realizing projects could be – amongst others – safety regulations for nature, connection to the electricity grid, or gaining local support for the project ().

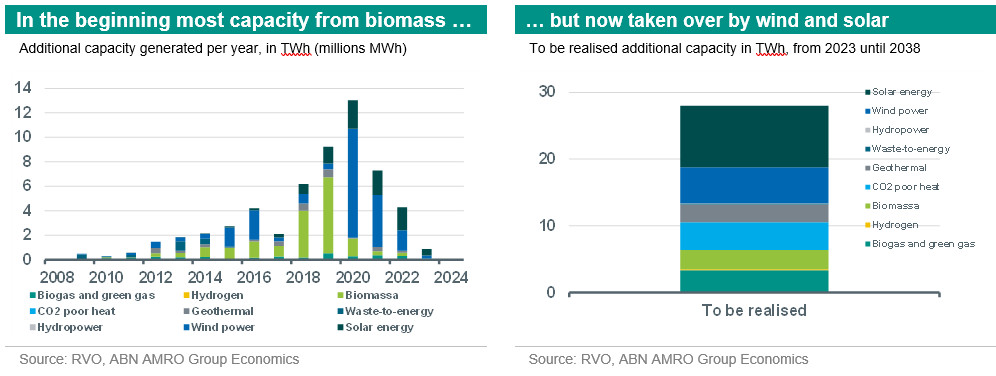

Most of the additional capacity generated by subsidized projects, in terawatt-hour (TWh), comes from biomass. This was particularly the case until 2019. After that year, wind energy took the lead. Together with solar power, wind is also largest source from which additional capacity will still be realized. This is visualized in the two graphs below. Several factors could have played a role in the switch from biomass to solar and wind energy when granting the subsidy. This could be sparked by the European Green Deal and the ‘Fit for 55’ package, but also the higher energy price caused by the Russia-Ukraine conflict, and prioritizing energy security more generally. Additionally, a shift in policy focus took place as since the start of the SDE++ subsidy, the attention has shifted to CO2-reduction rather than energy production ().

There are still many projects that have recently received access to the subsidy scheme, and they still are to be started. The maximum period with which the projects are realized is 15 years, meaning that there is still about 28 TWh of yearly generated capacity in the pipeline until 2038. The right-hand figure below shows the expected production of subsidized projects until 2038.

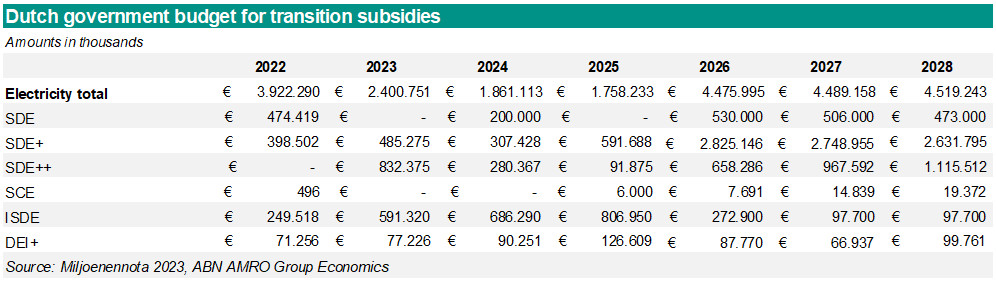

What could this mean for Dutch government expenditure?

In the coming years, funds originating from the subsidy schemes are expected to increase, though more gradual than was budgeted in 2022. Energy prices have been high, meaning that the government had to provide less funding from the subsidy scheme. This is also visible in the subsidies granted and scheduled for the upcoming years, where the total subsidized amount decreased significantly (see overview below). The remaining funds were and can be used for other government plans. For instance, in the last Miljoenennota (the Annual Budget publication) it was stated that “To cover the climate package in 2025, funds from the Sustainable Energy Subsidy (SDE), which fall under the Rijksbegroting (general budget) ceiling, have been used. In 2025, therefore, over €2.3 billion has been transferred on balance from Rijksbegroting ceiling to investment ceiling.”. Further ahead, as displayed in the overview below, funds originating from the subsidy schemes discussed in this publication are expected to increase.

Challenges to effective subsidy schemes

As discussed above, making substantial investments in clean technology projects is becoming more and more challenging even with the presence of subsidy schemes. A recent firm level survey by the ECB () reports that three quarters of firms have plans to invest in clean technology projects. However, the cost of financing is an issue. Half of the surveyed firms identified too high financing costs – as a result of the tightening of monetary policy by central banks leading to high interest rates and tightening financing conditions – as posing a significant obstacle to invest. Furthermore, firms find subsidized loans as important tools to enhance investments in green technologies, while public guarantees are viewed as insufficient. There is a major market inefficiency in Europe, as there is a huge pile of private funds ready for ESG investments, but there are limited investments taking place.

The success of the subsidy schemes depends in large part on the absence of any obstacles that hinder the transition process. That is, the problem of insufficient low carbon investments can also be driven by bottlenecks, such as unclarity of future regulations, long permitting times, and limits to infrastructural capacity. These form constraints and challenges facing the transition and adversely undermine any subsidy scheme in place. For the Netherlands, there are two constraints in particular: labour market tightness and nitrogen limits. In the considerable sustainability efforts that need to be made, professionals for the energy transition are essential but unfortunately hard to find. Dutch labour market shortages are substantial in general, but for occupation in the energy transition related activities they are even greater (link). Labour market tightness poses practical challenges, for instance for government plans. The second constraint comes from nitrogen limits, as it delays the expansion of electricity channels but is essential in laying the foundation for the transition. The cap on nitrogen pollution thus affects the construction of electricity networks, but also construction and infrastructure generally (). Because of these nitrogen constraints, some projects are currently on hold and awaiting further news. The longer it stays this way, the more difficult it is to reach the climate targets for certain sectors as now the foundations for the transition need to be made (). For example, the current limited grid capacity is a major cause for postponing investments in renewables, which in turn delays investments in green hydrogen. The latter is necessary to decarbonise hard to abate industries where electronification is not possible.

Furthermore, a disadvantage of the subsidy schemes is that they have a large administrative burden. The subsidy grant depends on energy prices and is determined in a backward looking way. This increases the administration that comes with the projects and finances (), which also poses limits on possible solutions or extensions.

Conclusions and recommendations for successful subsidy schemes

This article we provided an overview of the subsidy schemes to enhance the development and investments in clean technologies that match the Dutch transition agenda. We laid down the background of these subsidies and their goals. We moved afterwards to their status, effectiveness, practical implications, and highlighted the link to the Dutch government finances.

We conclude that the current Dutch subsidy schemes are appropriate to stimulate and incentivize corresponding clean investments. Also, these subsidy schemes prove to be very popular among SMEs. However, considering the above-mentioned challenges, we emphasise the need for a dynamic, timely, and proactive subsidy scheme that considers the developments in the market environment to avoid delays or fall backs in the transition process. For example, last month offshore auction in the UK did not receive any bids mainly because the subsidy strike price did not take into consideration the increase in inflationary pressures on the industry-wide production cost. In addition, coordinating the different components of the transition process is essential for keeping the scheme up to date to reflect the impacts of any emerging obstacles. Finally, subsidy schemes for clean technologies should be aligned with other climate policies, such as carbon pricing, to achieve a timely, orderly, and efficient transition.