SustainaWeekly - Lack of personnel an obstacle to energy transition

Professionals for the energy transition are essential but also unfortunately hard to find. In this week’s SustainaWeekly we quantify the shortages of transition professionals in the Netherlands compared to the overall labour market using our labour market indicator. We go on to look at regional differences as well as whether there are other carbon-intensive sectors who could release workers who have similar skill sets. In a separate note, we analyse recent ECB bank bond issuance trends. In our final note, we assess the main determinants of the European Union emission allowance (EUA) price from the demand and supply side, along with shedding the light on the relationship between EUA price and the transition process.

Economist: Professionals for the energy transition are essential but also unfortunately hard to find. The shortages per profession in the energy transition vary. Shortages also vary by region and can be more evenly distributed if workers are enticed to travel. CO2 reductions in other sectors could slow labor demand in some sectors, making more workers with similar skills available to alleviate some of the shortages in transition professionals.

Strategist: Issuance of euro-denominated bank bonds slowed down in Q3, also affecting issuance of ESG labelled bank bonds, which dropped by 39% versus Q2. But the share of ESG bank bonds in total issuance held up firmly. Moreover, issuance of ESG-labelled bank bonds is still well on track to exceed last year’s figure. Most ESG bank bonds are in senior format and have a green label.

Policy & Regulation: EU carbon emission prices are governed by supply and demand forces. The supply of allowances is pre-determined by policy, while demand for allowances would be driven downwards by higher abatement efforts and more investments in renewables. The level the carbon price affects the feasibility and business case for low emission technologies and, in consequence, the transition towards these technologies.

Energy transition falters due to lack of personnel

In the coming years, considerable sustainability efforts must be made. Professionals for the energy transition are therefore essential but also unfortunately hard to find.

The shortages per profession in the energy transition vary. Shortages also vary by region. The shortages can be more evenly distributed if workers are enticed to travel.

As a thought experiment, we look at what CO2 reductions in other sectors might mean for the tightness in the energy transition

This is expected to slow labor demand in some sectors, which could be positive for the energy transition where additional labor demand is expected

Not enough hands for energy transition

Considerable sustainability efforts must be made in the coming years to reduce CO2 emissions by 55 percent in 2030 compared to 1990 levels - in line with the European Commission's Green Deal. The availability of personnel is a growing stumbling block to achieving the required energy transition. Electricians, installation, insulation, and maintenance technicians and insulators are all badly needed but hard to find, the shows.

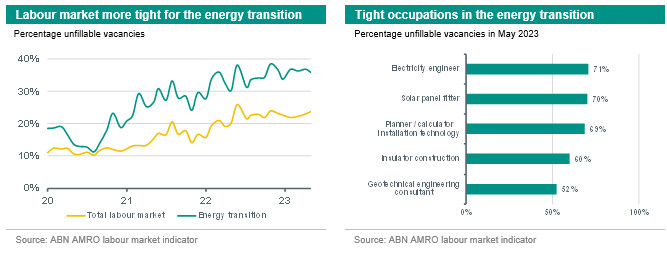

Professionals for the energy transition are unfortunately in short supply. At the end of May, almost 36 percent of vacancies in occupations related to energy transition were unfillable. This means that almost 36 percent of all vacancies that are outstanding within the energy transition cannot be filled by the job seekers who want to fill a profession in the energy transition and are able to fill this vacancy within a certain search radius (willingness to travel). We rely on our labor market indicator, which uses data from Werk.nl to take into account job seekers' job preferences and how far they are willing to travel for a vacancy. Relative to the tightness for all occupations, we see a sharp difference. Indeed, in May, 23.7 percent of all job openings were unfillable. The labor market shortages are in general substantial but for occupations in the energy transition, they are even greater.

Zooming in on these energy transition jobs, the shortages vary by occupation. Engineers for electricity grids, solar panels and insulators in construction are in great need of new personnel. On the other hand, environmental experts are not in short supply.

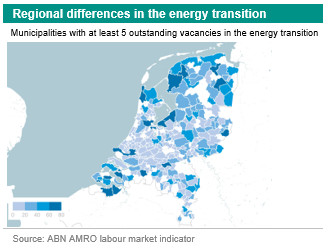

Regional differences reveal opportunities

Regionally, there are also large differences in the labor market tightness of energy transition occupations. The top five municipalities of Lelystad, Schagen, Den Helder, Terneuzen and Sudwest-Fryslan. We also see a higher percentage of unfillable vacancies in large cities. For example, in the municipalities of Rotterdam, Groningen, Breda, 's-Hertogenbosch and Amsterdam, the percentage of unfillable vacancies in energy transition is above 60 percent.

These large regional differences also mean that a relatively small adjustment can alleviate average shortages. For example, workers can be enticed to commute longer distances. By doing so, the tightness can be more evenly distributed across the country.

Reduction of CO2 emissions could create labor market space

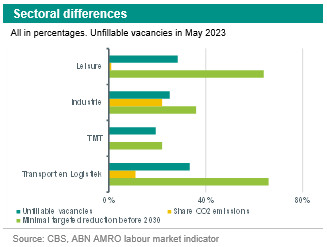

On the road to lower emissions, there will be sectors that will reduce their CO2 emissions. As a thought experiment, we look at what this could mean for the tightness in the energy transition. We select a group of sectors with low or high CO2 emissions, but with occupations that connect to occupations in the energy transition. This allows us to see what lower labor demand in high CO2 sectors can mean for the tightness in the energy transition.

It is expected that for some sectors, the reduction of CO2 emissions can slow labor demand. This is positive for the energy transition in which additional labor demand is actually expected. The distributional issue of labor is ultimately a political choice, but by shining light on information inequality, we hope to generate more insight into the possibilities for labor market dynamics.

To make this a little more concrete, we use the transfer . This data consists of alternative occupations that connect to one other occupation. This connection can come, for example, from similar skills needed to perform the work. We also use data from CBS on CO2 emissions per sector and the minimum reduction for 2030. In this thought experiment, we look at the leisure, manufacturing, TMT and transport and logistics sectors. These sectors contain occupations that, according to the UWV, have potential for a transition to an occupation in the energy transition.

There are two occupations in the energy transition that have many connections to other occupations. The first profession is solar panel mechanic. Occupations from which a transition can be made from sectors with relatively high CO2 emissions - industry and transport and logistics - include technical service employees and warehouse and shipping employees. A switch to the profession of solar panel mechanic can also be made from less CO2-intensive sectors. These include cab and private drivers, and audio-visual, image, sound and lighting technicians from the leisure and TMT sectors.

The second profession that finds a lot of connection is account manager business services; for example, as an energy consultant. Again, a transition can be made from both carbon intensive and less intensive sectors. Think of professions such as travel consultants, travel agents and hotel receptionists. But also trainers in communication skills and managers in logistics, transport, shipping and distribution.