ESG Economist - From 55 to 90…the EU’s new climate target

The European Commission has proposed a new emission reduction target for net GHG emissions of 90% by 2040 compared to 1990 levels, building on the 55% reduction it hopes to achieve by 2030. The Commission does not propose any policy measures, but presents an impact assessment and aims to inform the next Commission for it to set out a legislative proposal and policy framework. The proposed target is at the low end of the scientific advice, and would likely not be enough to keep within the carbon budget consistent with 1.5 °C on the basis of our calculations and current share. The impact assessment shows that investment needed to achieve these outcomes are enormous. It would need to total around 1.5 trillion euros annually, almost double seen in the last decade.

90 will become the new 55

The European Commission (EC) has proposed a new reduction target for net GHG emissions of 90% by 2040 compared to 1990 levels, building on the 55% reduction it hopes to achieve by 2030.The Commission does not propose any policy measures. However, it does present an impact assessment. It intends that this communication will ‘pave the way for a political debate and choices by European citizens and governments on the way forward’. On this basis, it will be the next Commission that will make the legislative proposal to include the 2040 target in the European Climate Law and that will design the post-2030 policy framework. In this note, we assess the ambition of the new target and set out what is needed to meet it, including the implications for investment spending.

How ambitious is the new target?

The proposed 90% target was selected after considering three options: 1. Up to 80% and consistent with a linear trajectory from 2030 to net zero in 2050; 2. At least 85%, corresponding to a range of 85-90%, which is in line with the level that would be achieved if the current policy framework is simply extended; 3. At least 90%, corresponding to a range of 90-95%, which corresponds with the advice given by the European Scientific Advisory Board on Climate Change (ESABCC). Indeed, the 90-95% range is the option seen as the ‘only option…that does not put at risk the EU’s commitments under the Paris Agreement’.

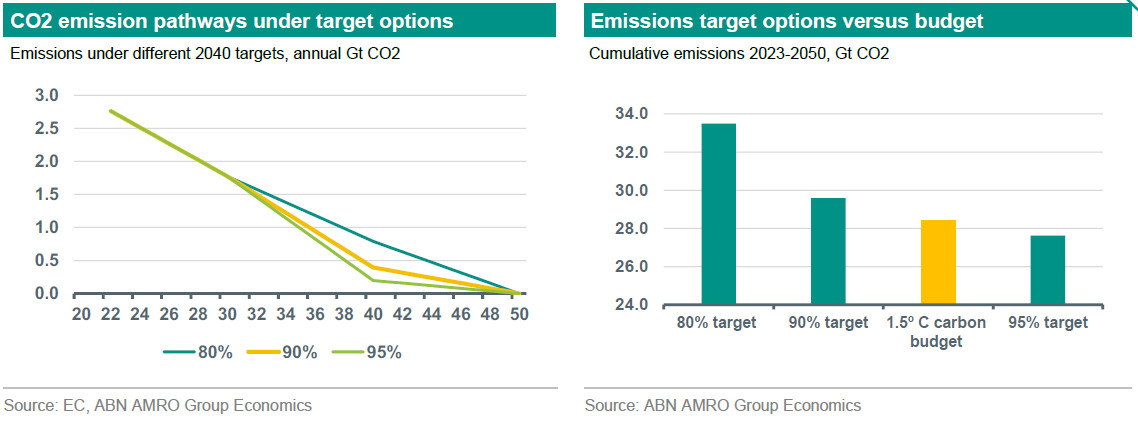

We computed the annual emission pathways in three scenarios (see chart on the left below). All three pathways assume that the 55% target is met as well as a linear trajectory between 2040 and net zero in 2050. However, they differ in what happens between 2030 and 2040. In the first trajectory we assume emission reduction of 80% by 2040 compared to 1990 levels, corresponding to scenario 1. In the second, we set out a pathway consistent with the proposed 90% target (which is the upper bound of the EC’s scenario 2 and lower bound of its scenario 3). In the final pathway we assume emission reduction of 95% by 2040 (which corresponds to the upper bound of the EC’s scenario 3). While the first pathway shows a linear pathway between 2030 and 2050, the other two show relatively deeper cuts in 2030-2040. Especially in the last pathway, the EU would not be too far off net zero by 2040.

While all trajectories reach the fabled net zero mark in 2050, this is a necessary but not a sufficient condition to meet the ultimate goal, which is path for emissions consistent with the EU’s contribution to limiting global warming to 1.5 °C. As it is cumulative emissions – the so called carbon budget on a global level – that contribute to the level of global warming. We can then size down from global carbon budget to the EU’s contribution to it to arrive at a regional carbon budget.

We start with the IPCCs estimate that the global carbon budget at the start of 2020 consistent with limiting warming to 1.5°C with a likelihood of 50%was 500 GtCO2. We then adjust that downwards using estimates from the Earth System Science Data to account for the emissions that we have seen since then, which leaves a smaller budget of to 380 GtCO2 for 2023-2050. Any particular country or region’s ‘fair’ share of the global carbon budget is a contentious topic, but we assume a share in line with the current proportion of emissions (see our previous notes and for more on this). We show the resulting carbon budget for 2023-2050 for the EU for 1.5 °C in the chart on the right above (yellow bar) compared to the resulting cumulative emissions for the three pathways we sketched (chart on the left).

As can be seen in the chart, achieving the 90% target would still actually leave the carbon budget above the one consistent with 1.5 °C, whereas the 80% is not even close. A 95% target would result in a carbon budget below the 1.5 °C one and in actual fact the midpoint of a 90-95% range is the one consistent with 1.5 °C. It seems therefore that a 90% target for 2040, while ambitious, might not be quite ambitious enough.

What is needed to meet the 2040 target?

The EC sets out a number of conditions that need to be met to achieve the 90% target. First of all, the full implementation of the 2030 energy and climate policy framework. In particular, it calls on member states to take measures to implement the commonly agreed policies and legislation necessary and to ‘increase ambition’. Given the proximity of 2030, this is a matter of concern. Starting from recorded data in 2022, emissions would still need to fall by around 35% from that level to hit the EC’s target for the end of this decade (55% reduction compared to 1990 levels). Assuming the target for 2030 is met, emissions would still need to fall by around 78% in the next decade to meet the 2040 target. So a failure to meet the 2030 objective would make meeting the 90% 2040 target even more challenging as emissions would need to fall at an even faster rate. Perhaps even more importantly, above pathway emissions over the next few years would shrink the carbon budget more quickly, meaning that a 90% target (even if met) would leave cumulative emissions further above a 1.5 °C carbon budget.

Second, the Commission asserts that the transition needs to be ‘just and fair’ for people. Public policy and funds should be employed to support low-income households to make decarbonisation investments as well as helping to alleviate the direct impact of carbon pricing where needed. It noted that the ETS funded Social Climate Fund will mobilise EUR 87bn to support vulnerable households, while member states are obliged to spend their overall national revenues for climate and energy purposes, including addressing the social impacts of the transition. Apart from the ethical dimension, the EC’s focus on this topic may also reflect concerns about signs of wavering public support for decarbonisation policies in some cases.

Third, the transformation of the EU’s energy system both on the supply and demand side. The share of electricity in final energy consumption would need to double from 25% today to around 50% in 2040. At the same time renewable and nuclear energy would need to generate over 90% of electricity consumption by that point and the consumption of fossil fuels would decline by roughly 80% compared to 2021 levels.

A faster roll-out of novel technologies would be needed after 2030. With regards the industrial sector, the achievement of the 2040 target would need early deployment of carbon capture (see here), which would reach around 140 Mt/CO2 annually. Hydrogen production would surge to 88 Mtoe in 2040 compared to an estimate 9 Mtoe in 2030, as it would be needed to produce e-fuels (see here) to help decarbonise hard-to-abate sectors such as aviation and maritime transport. The fast deployment of these and other zero and low-carbon technologies is seen as creating a large domestic market for clean-tech manufacturers.

A more than quadrupling of the electrification of road transportation would be necessary in 2031-2040. According to the EC, the share of zero-emission vehicles would rise to 60% for cars, above 40% for vans and just below that for heavy-duty vehicles. In the buildings sector, much of the acceleration in renovation rates would be seen in the coming years as part of meeting the 2030 target, but rates would need to remain relatively high after that. For residential buildings, renovation rates jump to 2.2% in 2030 from 0.9% in 2020, and then slow to just below 2% towards 2040. This would lead to further improvements in energy efficiency for residential buildings, but a decrease in energy consumption is necessary across all end-use sectors. Compared to 2021 levels, energy consumption in the residential sector would fall by 45% in 2040; 42% in transport and around 30% in services and industrial sectors.

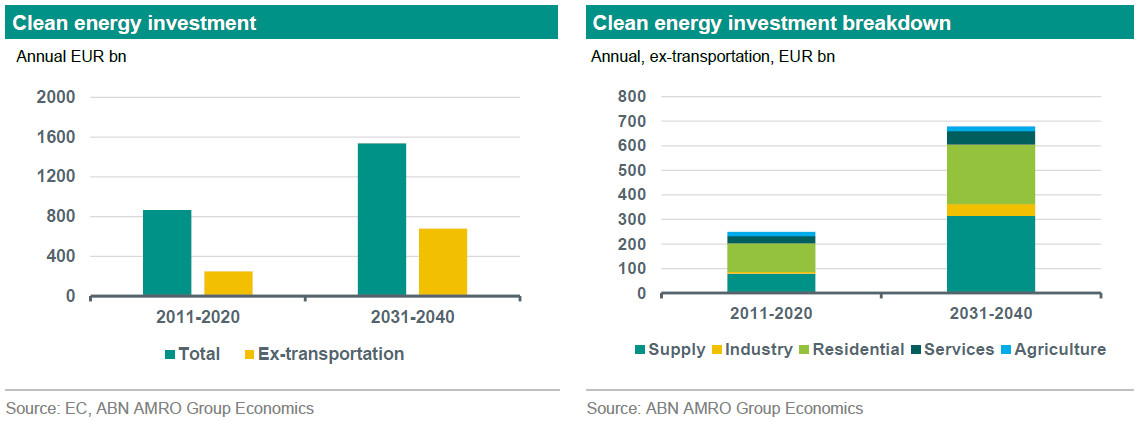

Another important condition to meet the 2040 target is a sharp step up in clean energy investment. The EC presents estimates of investment needs for the 2031-2040 period both on the supply and demand side compared to the 2011-2020 period. We present these in the charts below. We use the average numbers for the EC’s options 2 and 3 as the midpoint is most representative of what is consistent with the 90% target.

The chart on the left shows that total clean energy investment would need to average roughly EUR 1500bn per annum in the years leading up to 2040. This compares to total recorded green investment over the last decade of EUR 865bn. Typically, transportation is excluded from the total numbers given that the numbers for this sector includes large expenditures for passenger cars (around 60% of the total). Excluding-transportation, the required increase in investment is greater, at EUR 680bn annually, compared to EUR 250bn in 2011-2020. The chart on the right shows the breakdown by sector. The largest absolute increases are in energy supply and for the renovation of the building stock. The annual investment need ex-transportation amounts to 3% GDP over the 2031-2040 period, which is 1.5% GDP above the 2011-2020 period, but broadly in line with the EC’s previous investment need estimate for 2021-2030. Given historical trends in the investment to GDP ratio, this would be very challenging but not unprecedented.

Emission reduction target for 2040 might need to be scaled up

The EC’s proposed new emission target is ambitious, but our analysis of the remaining carbon budget suggests that somewhat higher emission reduction would likely be necessary for the EU to remain consistent with a 1.5 °C trajectory. Indeed, that even assumes that emission reduction over the next few years is in line with current targets. If it is not, the carbon budget may shrink faster than what we have assumed, meaning that there might be even more to do in the 2031-2040 period. Such a situation would place policymakers in between two unwelcome scenarios. On the one hand, a sharp and potential abrupt step up of the stringency of climate policy. This would have the potential to lead to a disruptive transition with significant economic fall-out. On the other hand, the EU failing to meet its international obligations, which can have far-reaching effects on policies in other countries, given its leadership role in terms of climate ambition. In this sense, the EC’s analysis of the challenges over the decade after this one stresses the importance of meeting the targets over the next few years.