ESG Economist - COP28’s mixed bag

During COP28 little progress was made in increasing the ambition of the 2030 targets. No “phase-out” but “transitioning away” from fossil fuels: significant but insufficient step. Countries pledged to triple renewables capacity. No deal on international framework for carbon credit markets. The loss and damage fund saw pledges (though falling short of what is needed) and concrete steps.

Introduction

From 30 November until 12 December the 28th Conference of Parties (COP) to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) was held in Dubai, United Arab Emirates. On 13 December, one day after the Conference ended, the concluding statement was published (), After a COP preview in our Sustainaweekly publication (), in this note we discuss the results and conclude mixed progress.

Little progress in increasing the ambition of the 2030 targets

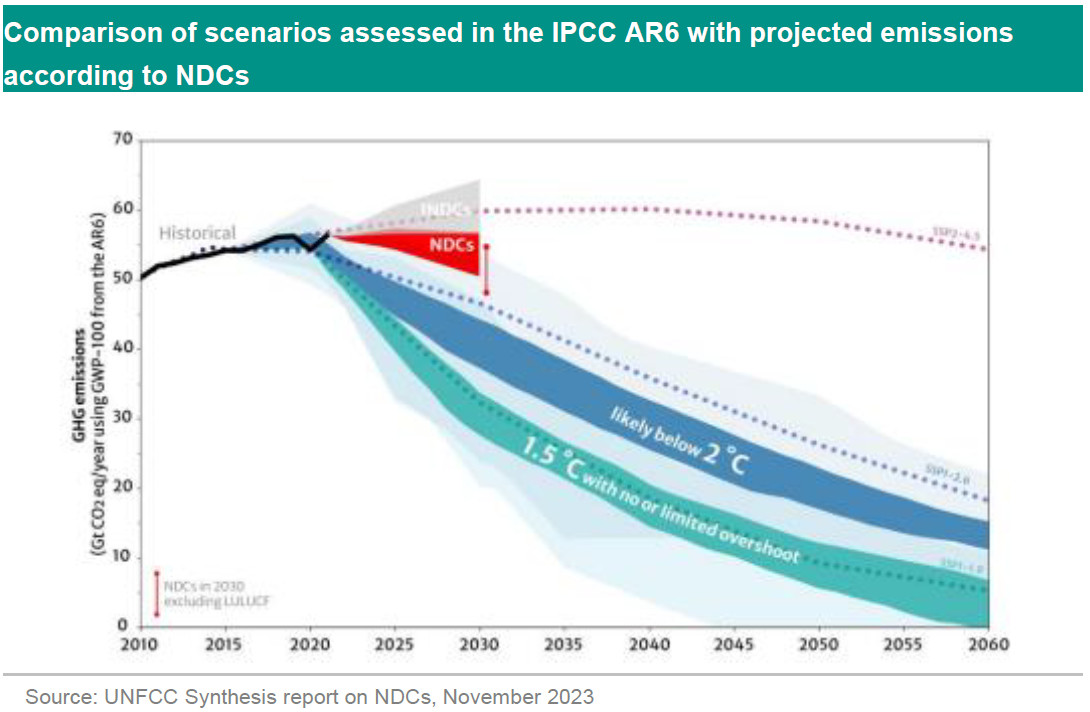

An important agenda point at COP28 was the Global Stocktake, in which issues are assessed and gaps identified related to where the world stands on climate action and support. Combining countries’ progress towards the Paris goals, the planet is currently on track for 2.1°C to 2.8°C of warming according to the UNFCC’s Synthesis Report on NDCs (), taking into account implementation of NDCs up until 2030 and depending, among others, on assumptions on the implementation of conditional elements, further emissions reductions beyond 2030, and inherent climate uncertainties. This is down from 4°C before the adoption of the Paris Agreement, but far off the 1.5°C (or at least below 2°C) target established back in 2015.

The stocktake recognises the science that indicates that global greenhouse gas emissions need to be cut 43% by 2030, compared to 2019, to limit global warming to 1.5°C. With the same wording as in the COP27 concluding statement, the COP28 decision on the global stocktake “requests Parties that have not yet done so to revisit and strengthen the 2030 targets in their nationally determined contributions as necessary to align with the Paris Agreement temperature goal”. The agreement calls for all parties to set ambitious, economy-wide emission reduction targets. Currently, however, the stocktake notes that the world is off track when it comes to meeting the Paris Agreement goals. Even if all current pledges were to be fulfilled, the world is not on track to limit warming to 1.5°C or below 2°C.

Phasing out, down, or transitioning away from fossil fuels

UNEP states that for the window to limit warming to 1.5°C to remain open, among others, investments in high-emission activities need to be phased out. According to the IEA, investment in oil and gas currently is actually almost double the level required in the Net Zero Scenario in 2030, signalling a clear risk of protracted fossil fuel use that would put the 1.5 °C goal out of reach. This promised to be a major point of contention in COP28, with the discussion focussing on “phasing out, versus phasing down”. In previous conferences, it was generally about (just) coal. The word “phase-out” (of fossil fuels) made it into the draft document during the negotiation process. But it was no longer in the final text, which mentions “transitioning away from fossil fuels in energy systems, in a just, orderly and equitable manner accelerating action in this critical decade” while also mentioning “transition fuels can play a role in facilitating the energy transition while ensuring energy security”. This is clearly less ambitious and more vague than “phase-out” and it has more qualifications and caveats, such as the one on transition fuels. Still, it is a significant (albeit insufficient) step, marking the beginning of the end of the fossil fuel era.

Pledge to triple global renewable energy capacity

The going has been easier on the pledges and progress for renewables: this is clearly a less contentious issue in which considerable progress has already been made in many countries. Global annual renewable capacity additions increased by almost 50% in 2023, the fastest growth in two decades, according to the “Renewables 2023” report the IEA just released ().During COP 28, a pledge was made to triple global renewable energy capacity by 2030 and double the speed of energy efficiency improvements. The pledge includes a commitment to ‘”expand financial support for scaling renewable energy and energy efficiency programs in emerging markets and developing economies”. This Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency Pledge () could, if fully implemented, close about a third of the gap between current policies and 1.5°C in terms of 2030 targets. It has until now been signed by 122 countries (and the EU). However, it lacks some concrete interim goals, and does not count all large emitters under its signatories.

No deal on key rules for carbon credit market

During COP28, there were prolonged negotiations on an international framework with key rules for approving carbon offsets and trading those offsets in a centralised UN-run system. The market for carbon credits has faced criticism for being opaque and lacking credibility. The international framework, first mentioned in Article 6 of the , is supposed to endorse standards for the carbon credit market and kickstart a mechanism for countries to compensate their own emissions by financing decarbonisation elsewhere. However, during COP28 the EU, UK and other countries opposed measures they perceived as weakening the system. Examples include a confidentiality clause in bilateral deals, and the option to cancel credits after they have been issued. The US and other countries such as Saudi Arabia, on the other hand, had been pushing for more flexible standards. In the end, talks on this issue failed to produce a result.

More concrete steps on the financial arrangement for loss and damage

During COP27 a fund (and broader funding arrangements) was agreed to provide assistance to poor countries that would suffer disproportionately from climate disasters. The agreement to set up a fund was hailed as a ‘historic step’ because of the underlying (albeit not explicitly stated) principle that wealthier countries that have contributed most to climate change, should support poorer countries that suffer most from it. But there were no details or concrete commitments following COP27.

On this issue an agreement to operationalise the fund (through the World Bank) was reached on the first day of COP28: the first time a significant decision was adopted on the first day. The fund will assist vulnerable developing countries in their response to economic and non-economic loss and damage from climate impacts such as extreme weather and slow onset events such as sea level rise. Commitments to the fund started coming in moments after the decision was agreed and currently stand at around USD 800m. Europe and countries such as the UAE made large contributions, while the US was criticised for the small size of their contribution (of a paltry USD 17.5m). In addition to the commitments to the fund, a platform for technical assistance to developing countries that are particularly vulnerable to climate change was also agreed. So far, however, pledges have fallen short of what is needed. Avinash Persaud, the influential climate envoy of Barbados, estimates that climate-related loss and damage costs are already exceeding USD 150bn annually and this number is expected to increase.