ESG Economist - Carbon costs for ETS companies are set to rise

In 2024, Dutch companies that fell under the European Emissions Trading System (EU-ETS) have emitted more CO2 than they did a year ago. According to the Dutch Emissions Authority (NEa), the increase was 2.3%, which amounts to approximately 1.4 million tonnes more CO2 emissions. In this short update on emissions among EU ETS companies, we not only look at emissions in the Netherlands, but also compare this with the trends in emissions in the other 26 EU member states. We also highlight the trend in carbon costs. Based on the expected CO2 price and the path of emissions towards 2030, we estimate the carbon costs in the period through to 2030.

In 2024, CO2 emissions from ETS companies in the EU-27 fell by 5%, while the Netherlands saw an increase of 2.3%

The current rate of emission reduction is insufficient to achieve the EU ETS 2030 climate target

Due to decreasing free emission rights and a rising CO2 price, the carbon costs will likely increase, which will stimulate decarbonisation

ETS emissions

The CO2 emissions of certain sectors are regulated by the European Union Emissions Trading System (EU-ETS). The EU-ETS is based on the ‘cap and trade’ principle. The ‘cap’ refers to the limit set for the total amount of CO2 that can be emitted by installations and operators covered by the ETS-system. The ‘trade’ has to do with the marketability of the emission rights.

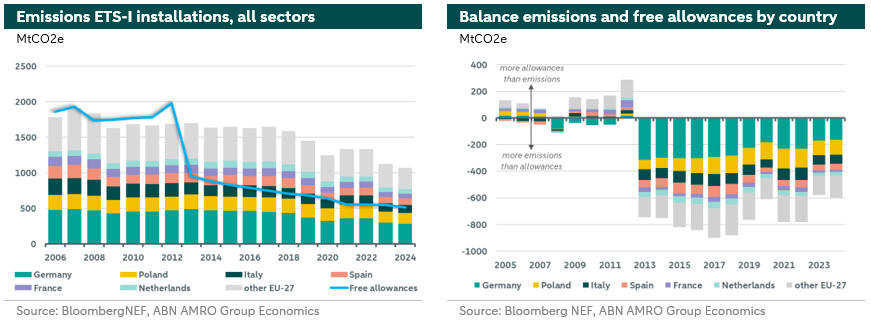

So far, the ETS-system had a positive impact in Europe. In 2024, CO2 emissions in the EU-27 decreased by 5%. However, this decrease is at odds with the increase of 2.3% on an annual basis of Dutch EU-ETS companies. In the Netherlands, industry and aviation primarily drove the increase. In 2024, the Netherlands saw a slight levelling off in the reduction of electricity production emissions, unlike the EU-27 where this sector significantly drove down CO2 emissions. For example, emissions from electricity production in the EU-27 fell by 12% in 2024. This was due to an increase in renewable sources and nuclear energy, combined with a decrease in the use of gas and coal.

However, the Netherlands was not the only country to record an increase in CO2 emissions among ETS-companies. Emissions also increased in ten other EU countries in 2024. Nevertheless, these were generally the relatively small countries in terms of GDP. Of the top six countries with large ETS-companies shown in the figure on the left above – and with a combined share of 70% of total ETS emissions – Spain, in addition to the Netherlands, also showed an increase in emissions (of 2%).

ETS-companies in the EU are allocated free emission rights for CO2 emissions to enable them to compete with companies outside the EU that are subject to less strict climate legislation. However, the number of free emission rights will decrease in the coming years according to a linear reduction factor: -4.3% from 2024 to 2027 and -4.4% from 2028 to 2030. In 2013, the number of free emission rights under phase 3 (2013-2020) of the EU-ETS system decreased significantly and a voluntary auction became the standard method for allocating emission rights. Since 2013, not a single EU country has had a surplus of free emission rights (see figure on the right above).

Rising carbon costs

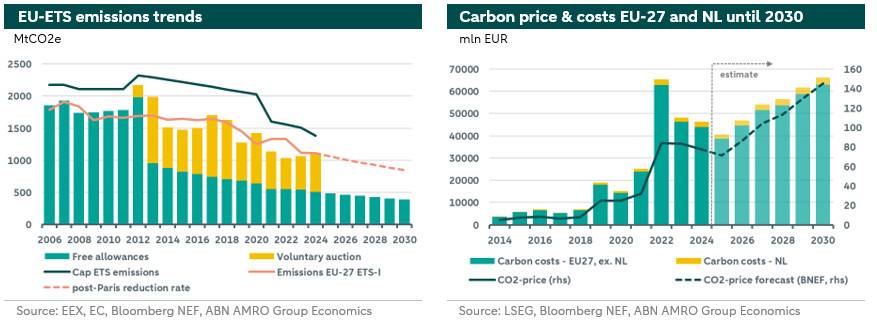

Approximately 45% of CO2 emissions in the EU are regulated by the EU-ETS. The EU-ETS aims to cut CO2 emissions by 62% by 2030 compared to 2005 levels. With the decrease in CO2 emissions in 2024, ETS emissions are approximately 50% below the 2005 level. This means that the 2030 target of -62% compared to 2005 is within reach. However, if the emission reduction path taken after the Paris Agreement (the ‘post-Paris reduction rate’ in the figure on the left below) were to continue, there will be an emission gap of 20% in 2030, compared to the EU-ETS goal. This means that more climate measures are needed than have been taken so far.

An emissions cap applies to installations and operators under the ETS-system for the entire EU. The cap is lowered annually in accordance with the EU's climate objective, with an annual reduction factor determining the pace of the reduction. Every year, ETS-companies must hand in enough emission rights to fully account for their emissions. If companies fail to do this and emit more CO2 than they are entitled to, they risk a fine of EUR 100 for every tonne of CO2 they emit over the limit. This fine per tonne of CO2 increases every year in line with the inflation rate calculated by Eurostat.

In 2013, a system change took place in the EU-ETS, whereby part of the free emission rights were included in a voluntary emission auction. Nowadays, ETS-companies can sell their surplus emission rights on secondary markets or purchase their deficit of emission rights at auction and secondary markets. The price of an emission right within this system is the EU-ETS price (CO2 price). There was from time-to-time an annual gap between the free emission rights plus the purchased emission rights and the actual emissions. This gap is partly filled on the one hand by the free emission rights for electricity production for member states with a relatively low GDP in phase 4 (2020-2030, Article 10c). Next to that, it was filled by the New Entrants Reserve (NER). These are the free emission rights for new installations and capacity expansions at existing ETS-installations. However, the gap is also determined by the unused (free) emission rights that have been granted to or purchased by ETS-companies in the past, particularly to heavy industry. Some of the abundant emission rights were sold over time, improving margins as a result. Others were saved, because an emission right does not expire within EU-ETS. These emission rights can be used at a later stage, in times when the emission reduction efforts fail.

Revenues from the auctioning of emission rights peaked in 2022 due to a sharp increase in the CO2 price. According to Bloomberg New Energy Finance (BNEF), the rising trend in the CO2 price is expected to continue until 2030 (see our notes on CO2 price trends and ). This also means that the carbon costs for companies that fall under the ETS-system will also increase. The number of free emission rights decreases every year, and the difference must be made up by either purchased rights at auction or by reduced emissions. The trend and calculation of the carbon costs in the period 2025-2030 in the figure on the right is based on the emissions according to the post-Paris reduction path. This results in more than EUR 66 billion in auction revenues in 2030. The Netherlands accounts for approximately 5% of the EU's total carbon costs. For Dutch ETS-companies, the annual carbon costs will also increase, parallel to the trend in the CO2 price. For all ETS-companies in Europe, investing in decarbonisation in the period up to 2030 will ultimately reduce carbon costs.

Conclusion

For years, free emission rights protected large ETS-companies in Europe from foreign competition. However, this proved to be a brake on investments in decarbonisation. With the increase in the CO2-price until 2030, the carbon costs for ETS-companies will only increase, providing an inventive to these companies to invest in decarbonisation. However, these investments are more difficult to realize in times of high energy costs, an additional CO2-tax and a potential decrease in export demand (due to the trade war). This squeezes margins even more, which were already under pressure. A more structural and long-term measure, however, is to further stimulate decarbonisation by ETS-companies and stimulate them to invest in low-carbon technologies. To make decarbonisation a success, it must be given top priority in policy. This requires full government support, not only in a financial sense, but also with transparent and long term policies. Eventually, more clean energy and low-carbon technologies go hand in hand with less price volatility (of energy) and less import dependency (of energy).