Dutch economy in focus - One swallow does not make a summer

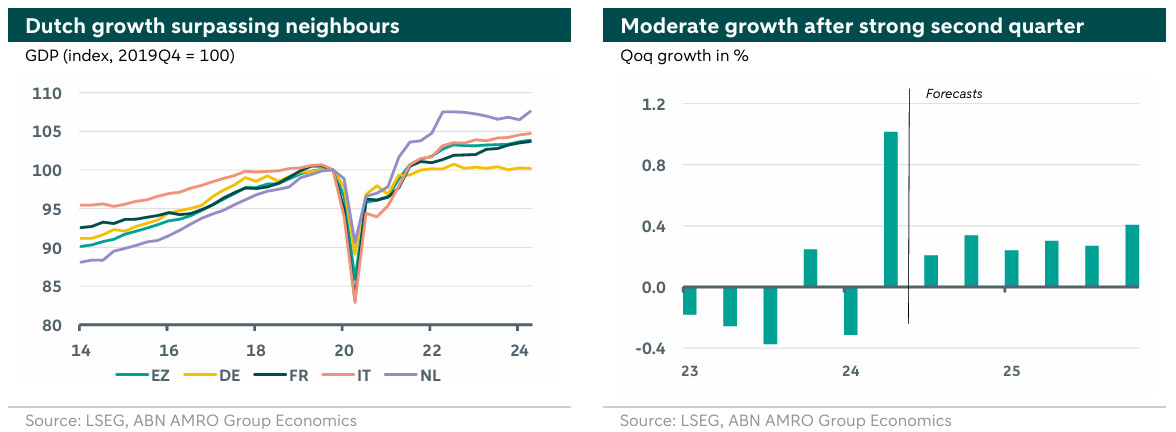

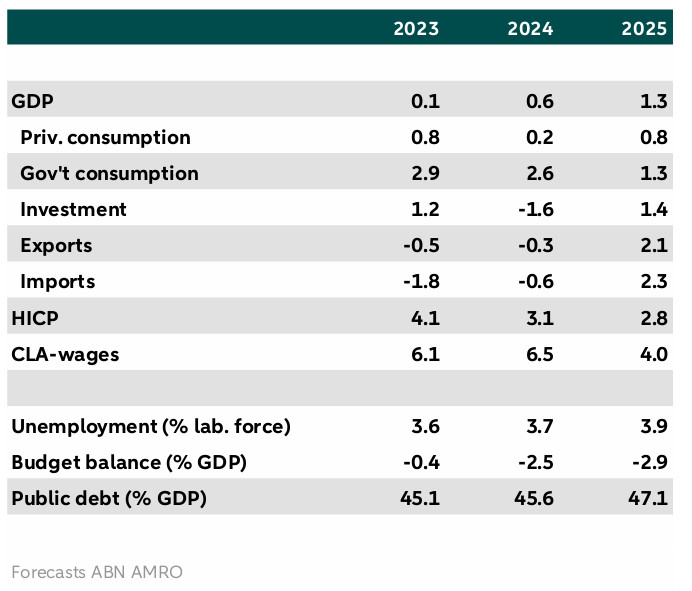

Surprisingly strong growth in the second quarter finds no continuation in the quarters after. High interest rates, weakness in manufacturing and reluctant consumers keep growth down. Growth picks up more next year as rates are cut further, global trade picks up, and consumer demand increases. We expect economic growth to average 0.6% in 2024 and 1.3% in 2025. Although the international situation is precarious partly due to geopolitical tensions. For instance, the Netherlands could be hit hard if Trump implements his plan for import duties (read more in box 1). The new cabinet has the luxury of looking further ahead on Prinsjesdag (budgeting day) now that the pandemic and the energy crisis are behind us and inflation has already fallen significantly (read more in Box 2).

A volatile first half of the year

In the second quarter of 2024, the Dutch economy experienced a surprising 1% q/q growth, driven by increasing exports and government consumption. This growth followed a contraction of -0.3% q/q in the first quarter, making the first half of the year volatile. There were also hefty revisions to Dutch statistical office (CBS) growth figures. Does this strong growth mean we can celebrate? No, because over the six months, the economy grew moderately by 0.7% and growth will remain modest in the rest of 2024. Only afterwards, when interest rates fall further and growth in the eurozone picks up, can the Netherlands also benefit in the form of higher GDP growth.

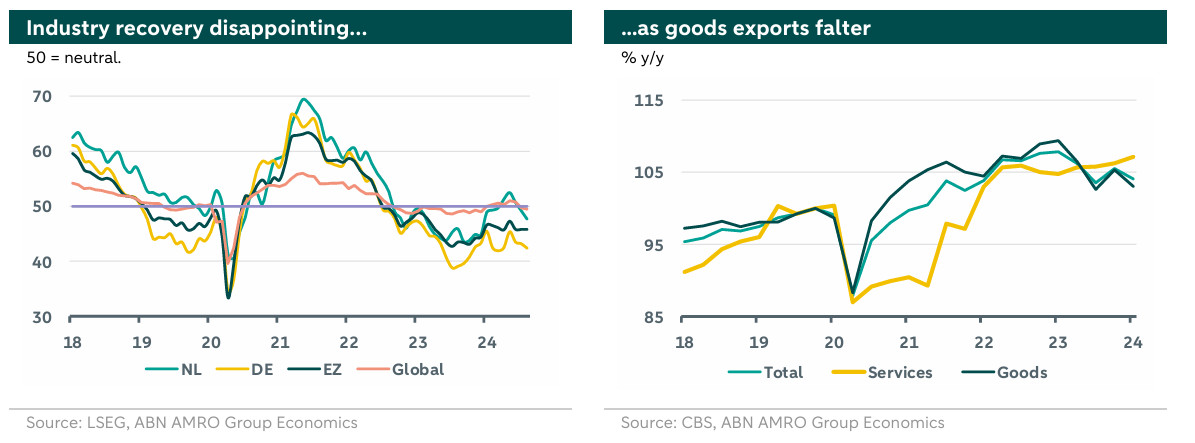

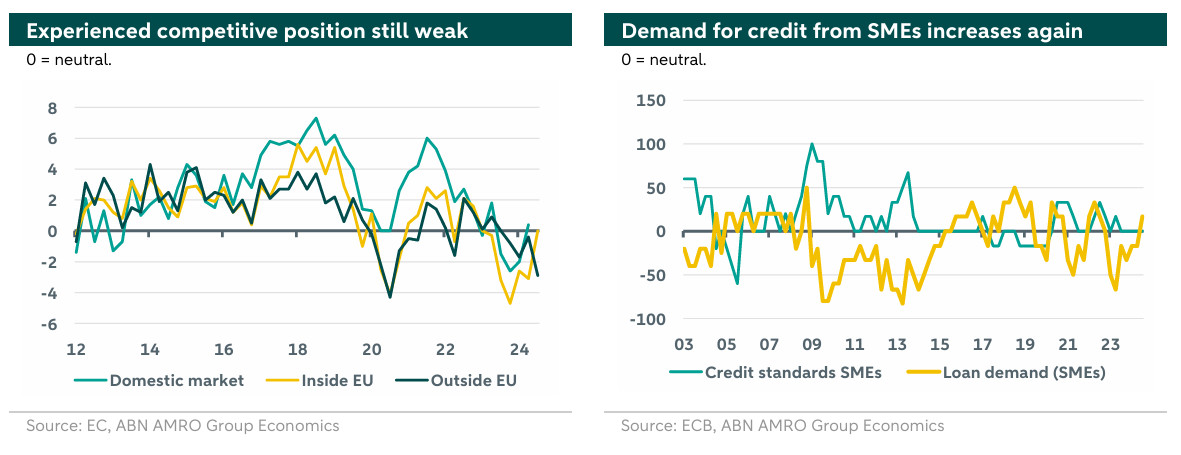

Weak competitive position and subdued demand hamper European industry

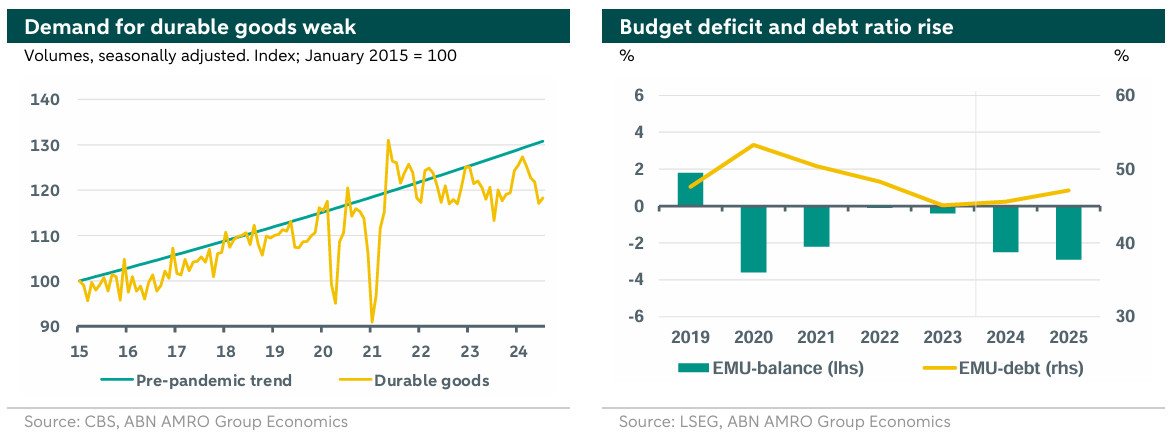

The Dutch economy is currently in a precarious international context. Although global trade is picking up somewhat, Dutch industry is not benefiting much from this as of yet. Dutch manufacturing companies are part of international value chains and suffer above average from the weak competitive position of the European, especially German, industrial sector. We see supply factors. The competitive position of industrial companies has worsened due to higher energy costs. But demand also plays a role. Growth in the eurozone leans mainly on strong demand for services. Eurozone and Dutch goods demand is lagging, as high interest rates squeeze demand. Indeed, when interest rates are high, investment costs are higher and the interest-sensitive sector, a major consumer of industrial products, underperforms.

Exports pick up in 2025 but geopolitical risks increase

The outlook for exports is mixed. Growth in exports will remain limited in the coming months. If rate cuts continue in 2025, growth in the will pick up. Eventually, Dutch exports will also benefit. This will therefore lead to a larger contribution of net exports to GDP growth. At the same time, the global recovery is fragile. The is slowing and continues to suffer from domestic real estate problems. Geopolitical risks are also increasing. In box 1, we mapped what possible US import tariffs, a plan by presidential candidate Trump, would mean for the Dutch economy.

Rate cut imminent but demand impulse still pending

With eurozone developing largely as expected, the likelihood of interest rate cuts by the European Central Bank (ECB) is increasing. Indeed, the favourable development of inflation coincides with a weaker-than-expected recovery of the eurozone economy. As a result, calls for less tight monetary policy are growing stronger. Already since June we expect the ECB's deposit rate to fall to 3% (currently 3.75) by the end of 2024. During the year, investors assumed a slower pace of interest rate cuts. But since August, the expectation of a 3% deposit rate has also been the consensus in financial markets. The pricing in of these rate cuts is also affecting financial market valuations. For instance, government bond yields fell in August. Because of the delayed pass-through of policy interest rates, it will take until 2025 for these interest rate cuts to have an effect on the economy.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

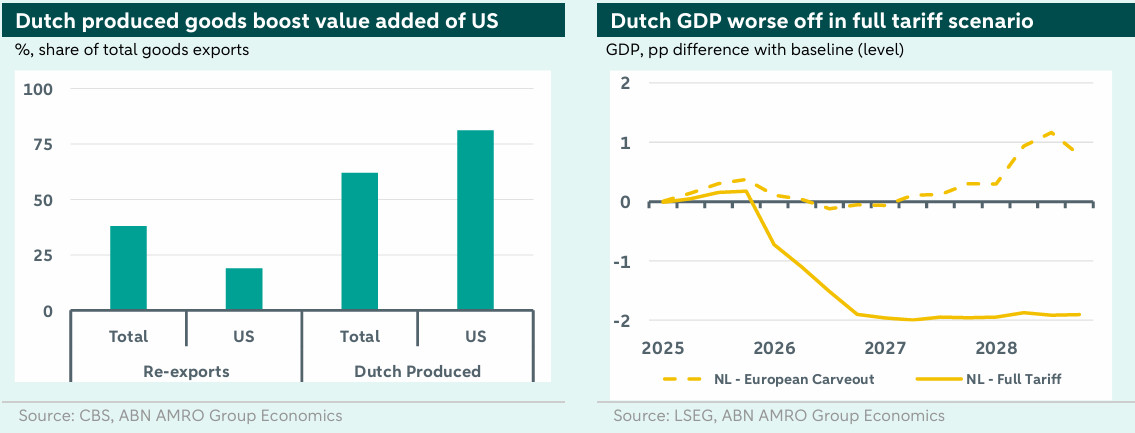

Box 1: Trump Tariffs and the Netherlands – Economic structure and position in supply chains amplify impact

In August's , we looked at the impact on the eurozone and the Netherlands of two scenarios in which Trump introduces import tariffs. In the 'Hard Trump' scenario, we assume import tariffs apply to all countries. In a second 'Soft Trump' scenario, we assume a situation in which the European Union receives an exception. As a trade-oriented country with a high degree of participation in global value chains, high-value added goods exports to the US and as an entry point to the European mainland, our analysis shows the Netherlands stands to be significantly impacted (positively and negatively) in both Trump tariff scenarios.

Dutch-US trade: Value-added and capital goods heavy.

Some 6% of Dutch goods exports are destined for the US, with around 20% constituting re-exports and 80% being Dutch-made goods. The value-added on domestic produce is significantly higher than for re-exports. This is visible in the GDP contribution of domestic produce exports to the US, which averages 0.8% of GDP (average 15-20) according to the . It ranks fifth, even taking into account EU countries. Capital goods are the biggest export product: machines and transport (22.6% of total exports to the US) and chemicals (15.4% of total exports to the US). The high degree of internationalization of Dutch trade also affects Dutch-US trade: from the product groups that Dutch firms export to the US, over half of the inputs needed are imported from other EU countries.

Hard Trump: International focus of the Netherlands means it is worse off than the broader eurozone

In the full tariff scenario, a global slowdown in growth and trade causes Dutch GDP to perform increasingly worse in the coming years compared to the baseline with no tariffs, with GDP a cumulative 2% lower by 2027. Relative to the broader euro area the Dutch economy is worse off. The impact is amplified by the fact that compared to the EU-average, the Dutch economy is more trade-orientated and is more international supply chains. However, to earlier tariff episodes, we initially observe a frontloading effect in 2025. The Dutch economy benefits from increased trade from companies anticipating the tariffs. From 2027 on, the GDP hit versus baseline stabilizes, but lower trade volumes still weigh on Dutch potential growth.

Soft Trump: Substitution later on means the Dutch economy profits after a global slowdown

In this scenario the euro area and the Netherlands in particular ultimately benefit from substitution effects, as US trade shifts from tariff-hit countries to the eurozone. The Dutch product mix helps here as Europe and the Netherlands become increasingly attractive to import capital goods from. The Netherlands can – depending on the precise rules of origin – source inputs from other trading partners which are hit by US tariffs, and export capital goods to the US without the tariff. However, in this scenario the Dutch economy is not fully isolated from adverse effects. The tariffs cause a global economic slowdown which is why Dutch GDP is lower in 2026 and 2027, after which the substitution effect dominates and the Dutch economy benefits. Outside the scope of this analysis, are potential additional trade restrictions on the semiconductor sector. The semiconductor sector has become a flashpoint in US-Chinese rivalry, making additional measures possible. This sector has become increasingly important for Dutch exports, and further restrictions could amplify the effects described below. (Aggie van Huisseling & Jan-Paul van de Kerke)

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

A difficult business climate

Due to weak growth prospects, geopolitical uncertainty and the tight labour market, companies are reluctant to invest. Investments have been lagging GDP trends since 2019. An additional reason for this, is the sharp decline in transport equipment investments, such as cars and commercial vehicles. However, helped partly by a packed government investment agenda, investment growth remains positive in the coming quarters. The annual figure for 2024 will nevertheless be negative, but this is due to statistical spillovers from 2023.

Bankruptcies rise further

Since the low point in mid-2021, the number of bankruptcies in the Netherlands has been rising again. Recently to above the average of 2019. We expect the increase in bankruptcies to continue in the coming quarters due to the pass-through of higher interest rates and the repayment of pandemic incurred debts. With this, the number of bankruptcies comes more in line with the state of the business cycle. In general, we see that the Dutch corporate sector is financially resilient.

Labour supply remains constrained

The worst stress has passed, but the labour market remains tight. The normalisation of the number of bankruptcies will provide relief, allowing labour dynamics to pick up a little. In the second quarter, a fall in the number of new job vacancies provided some relief, reducing tension to 1.08 vacancies per unemployed person. The number of employed persons and jobs also grew less strongly. In the agriculture, manufacturing, construction, information & communication and business services sectors, we see stagnation or even a decline in the number of employed persons and jobs. In contrast, employment continues to increase in the trade, public administration & government, education, care and culture & recreation sectors. The unemployment rate remains low in the coming years, given strong labour demand and limited available labour supply. The labour participation has reached a new record, with 73.4% of the population aged between 15 and 75 working.

Strong wage growth due to increase in minimum wage and labour market tightness

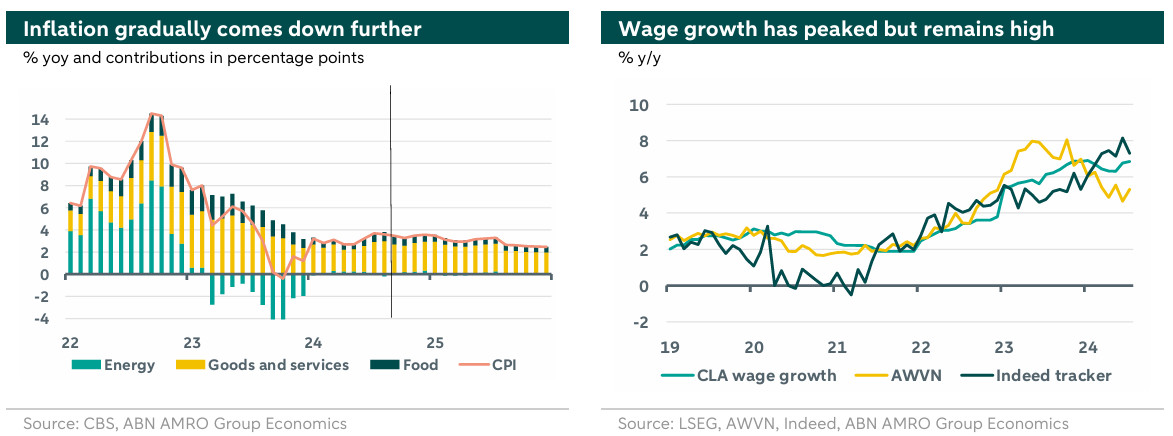

Wage growth declined at the beginning of the year, but picked up again recently, mainly due to an increase in the minimum wage. This has throughout the broader wage framework. In August, wage growth fell slightly again. Of the 547 collective agreements expiring this year, 362 have already been . Factors driving wage growth are inflation compensation, labour market developments and inflation expectations. In many CLAs, the loss of purchasing power has already been (largely) made up, which removes a major cause of strong wage growth. In contrast, the tight labour market gives workers more bargaining power and inflation expectations have stabilised at a somewhat higher level than before the pandemic. The notes that instead of the long-term average, higher wage figures from the past year are increasingly being used as a reference by CLA- parties. On balance, we think wage growth has peaked but will remain high for the rest of the year. We forecast a CLA wage growth of 6.5% for this year and of 4.0% next year.

Inflation remains a services story

Inflation is gradually falling further, but services continue to exert upward pressure. Wage growth plays a role, especially in contact-intensive services as margins are often smaller and the pass-through of wages is faster. The range where wage growth has a neutral effect on inflation corresponds to the inflation target plus productivity. We this at 2.2 - 2.8%. Current wage growth is significantly above this at 6.7%. In addition, housing rents were re-indexed in July. Rents (about 20% of the consumption basket) increased substantially. This increase is driving services inflation higher in the following 11 months. Food prices recently rose somewhat again due to the excise duty hike on tobacco implemented from 1 April 2024. This adjustment gets delayed effect, as initially tobacco stocks may be sold with old excise rates. The impact of energy prices on inflation is smaller this year than in previous years. Given the limited increase we expect for and , this will remain so for the rest of the year, although geopolitical developments continue to pose an upside risk to energy markets. Finally, industrial goods prices will be a negative contributor for the rest of the year given the weaker demand we see in the . All in all, inflation will fall further, to 3.2% this year and 2.9% next year; still above the ECB's 2% target.

Households appear cautious

Household spending has virtually stagnated in recent quarters. Households are more cautious than expected, despite their real income increase due to falling inflation and strong wage growth. In particular, consumption of (durable) goods is disappointing. Compared to before the pandemic, households are still a larger share of their income. In surveys, they indicate that saving is important at the moment. Possibly, they want to take advantage of increased interest rates; balances on bank deposits with longer maturities and interest rates are rising. The uncertain macroeconomic context and geopolitical tensions may also play a role in households' reluctance. In addition, bad weather played tricks on the hospitality sector, stimulus measures (such as the energy surcharge) have fallen away, and income growth may be uneven between different types of households. Given real income growth, we still pencil an increase in spending in the rest of the year.

Trend of budget deficits continued

Dutch public finances are in good shape at the start of the government. In the past two years, the budget deficit has been limited and the debt ratio hovers just above 40% of GDP, far from the European 60% rule. However, the direction public finances are moving in, is one of deterioration with high budget deficits and a rising debt ratio. By 2025, budget deficits are expected to reach 2.9% of GDP. Some 28 billion more will then be spent than will come in in tax revenues. This trend was already in place under the previous cabinet and the new cabinet deviates from it only slightly.

To avoid overspending, the cabinet proposes in the outline agreement to cut spending if, according to the CPB, the deficit exceeds 3%. Macroeconomically, it would make more sense to keep a larger margin, i.e. a lower budget deficit, while the economy is still doing relatively well. When the economic tide turns and social security spending rises and tax revenues fall, the government then still has room to stabilise the economy without having to immediately cut spending to avoid breaking its own and European rules. The cabinet's exact plans will become clear in the coming weeks. The details of the outline agreement are expected this week and the budget for the coming year will follow on Prinsjesdag (see Box 2 for a preview of Prinsjesdag).

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Box 2: Budget Day - Building blocks to cope with the impact of ageing still missing

Tuesday 17 September is Prinsjesdag (budgeting day) and the new cabinet will present its plans for the coming fiscal year. Because this time, Prinsjesdag is not ruled by crises (as during the pandemic and energy crisis), the focus can again go to the long term, to policies that will make the Netherlands future-proof.

One key long-term challenge is ageing. This is likely to lead to pressure economic growth, as the recruitment of new workers falters and domestic spending shifts towards labour-intensive healthcare. In addition, ageing leads to an increased burden of care on public spending. To keep resources for other social purposes, it is necessary to organise healthcare as effectively as possible.

We conclude that the measures already known from the Headline Agreement and the reports leaked to the press do little to cushion the expected impact of ageing on the economy.

Ageing population will pressure economic growth

Ageing puts pressure on future economic growth by slowing down production as the recruitment of new workers falters. It is therefore important to promote labour participation. The government wants to do this by lowering taxes on labour (lowering the tax rate in the first income tax bracket) and shortening the unemployment benefit period. The short-term effects of this are limited, as the labour market is already very tight and the number of long-term unemployed is particularly low. Even bigger gains can be made if the over-60s and people with a disability or chronic illness - two groups that are now often sidelined - enter the labour market more easily. Unfortunately, the government is not taking any specific measures to increase the participation of these two groups.

In addition, ageing leads to lower economic growth as domestic spending shifts towards healthcare, a labour-intensive sector with generally lower productivity and productivity growth. To achieve economic growth, the remaining production capacity needs to be used as productively as possible. This is done by investing in knowledge and training; but also by organising economic dynamism. That economic dynamism has been frozen in recent years by the support measures during the corona and energy crises. The cuts in the transitional compensation for redundant workers (as proposed by the government) do not contribute to improving economic dynamism. But, in particular, the proposed cuts to the Growth Fund, education and science, and restrictions on migration and foreign students will prove an obstacle.

Ageing population is associated with higher healthcare costs

Ageing also affects public finances, as care is largely publicly funded. In this respect it is unfortunate that the Integraal Zorgakkoord (Integral Care Agreement) - an instrument to organise future care as effectively and efficiently as possible in order to control healthcare costs that was, isn’t mentioned in the Headline Agreement. Prevention can also help keep the demand for and costs of care manageable. The government indicates that prevention is important, but does not put money aside for prevention. Instead, there is a threat of spending cuts for the agencies responsible for public health care. In addition to this, no money is earmarked for housing for the elderly, though in the Headline Agreement it is mentioned that local programming of owner-occupied houses should take into account sufficient housing for the elderly to promote mobility.

Currently there are substantial staff shortages in the care sector. The previous cabinet came up with the future-proof labour market for care and welfare programme. The new cabinet is cutting it back. Meanwhile it lowers the personal healthcare contribution, which will spur demand and make health care staff shortages even more acute. (Philip Bokeloh)

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------