Climate goals the Netherlands out of reach

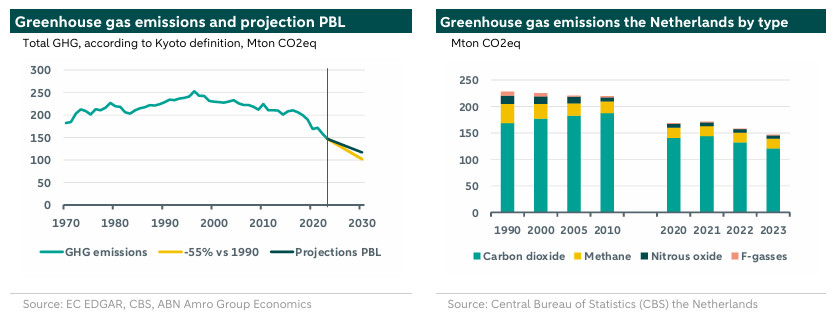

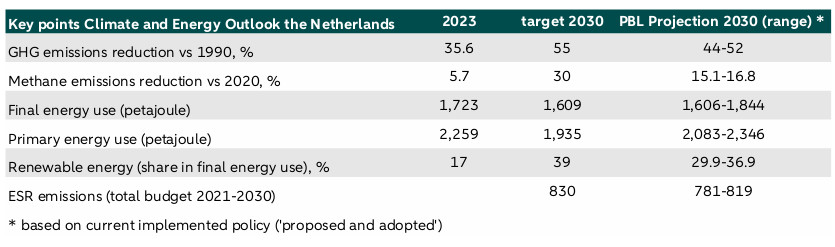

The independent PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency has published its annual Climate and Energy Outlook for the Netherlands (KEV) 2024 ……. as already became obvious after the publication of the policy plans and coalition agreement of the new Schoof government this summer, the PBL concludes that ‘reaching 2030 climate goal has become extremely unlikely and extra policy with rapid effect is needed’. The new government’s legal target for the net reduction of Greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions is set in line with EU regulations at 55% in 2030 compared to 1990, though this is less ambitious than the target of the previous government. According to the PBL current implemented policy (‘proposed and adopted’), puts the Netherlands on track for a reduction of 44%-52% in 2030, compared to 1990 levels. Including scheduled policies does not add much to this: a net 45%-52% reduction. Besides the targets for GHG emissions, the Netherlands probably also will not meet the separate global and EU targets for methane emissions, final energy use and the share of renewable energy. As the Netherlands is likely to be non-compliant with EU regulation, the risk that the government will be subject to infringement procedures has increased.

Introduction

After the new Dutch coalition government presented its main policy plans and coalition agreement this summer, it already became obvious that meeting the legal target for the reduction in Greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) had become unlikely (see our previous research note New Dutch government scales back climate ambitions, ). At the end of October, the independent PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency published its annual Climate and Energy Outlook of the Netherlands (KEV) 2024 (only in Dutch, ). It concludes that ‘reaching the 2030 climate goal has become extremely unlikely (lower than a 5% probability) and extra policy with rapid effect is needed’. In this note we will discuss the main takeaways of the PBL report. In a follow up note we will look more in depth at the sectoral climate goals and performances.

Reaching the 2030 GHG reduction goal is ‘extremely unlikely’

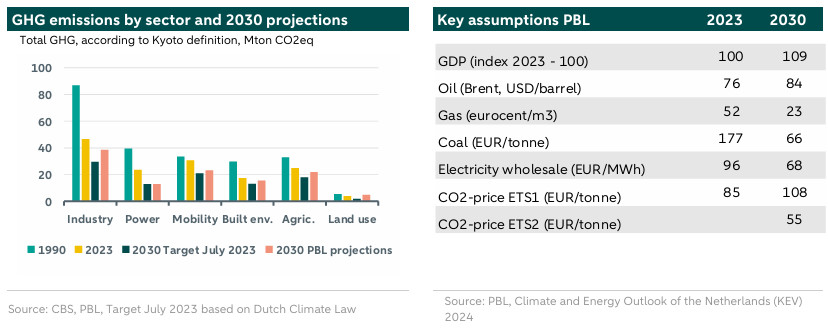

According to the PBL, it is extremely unlikely (lower than 5% probability) that the Netherlands will reach its legal climate goal of a 55% reduction in GHG by 2030. With current implemented policy (‘proposed and adopted’), the country is on track for a reduction of 44%-52% in 2030, compared to 1990 levels. Calculable plans (‘scheduled policy’) do not add much to this: a net 45%-52% reduction. The current projected emission reduction is 5 percentage points lower than a year ago. When measured in terms of levels, the estimated emissions in 2030 will be between 110 and 127 megaton CO2equivalent, whereas the target is 103 Mton CO2eq. To reach the goal with a probability of 50%, an additional emission reduction by 16 megatons in 2030 is needed; to reach the goal with an extremely high probability (95%), 24 megatons of reduction is required. Scheduled plans of the government can bridge only a small part of these reductions.

What are the main reasons for the slower GHG reduction?

The lower path of emission reduction is mainly due to setbacks in implementation, such as delays in offshore wind farms and stagnating production of green hydrogen. The PBL mentions that due to delay in the rollout of offshore wind farms its projection for the percentage of electricity that will be renewable in 2030 has fallen to around 70%, down from around 85% in the PBL’s previous projections. Moreover, political choices in the past year contribute to a lower projected emission reduction. This includes the cancellation of Pay as you Go (kilometre pricing in mobility) and policy changes by the new Dutch government (such as the wish for renewed manure derogation by farmers, reducing the excise duty on diesel paid by farmers, raising the maximum driving speed on motorways, lowering tax cuts on the purchase of EVs, abolishing the netting arrangement for the owners of solar panels, lowering the energy taxes on gas for households and cancelling the planned extra emission taxes for companies). Also higher final electricity demand results in more domestic fossil electricity production and higher emissions in the sector electricity, according to the PBL. In short, without new plans – and rapid implementation – the Netherlands will not reach its goal of 55% GHG reduction. A year ago, the PBL estimated that there was a 15% probability that the GHG reduction target would be met, versus a less that 5% probability (‘extremely unlikely’) at the moment.

Looking beyond 2030, the KEV also contains a projection for 2035 and a look towards 2040. The projection indicates that the 55% emission reduction goals set for 2030, will likely only be reached in 2035. This means that the speed of emission reduction under current policy is insufficient for climate neutrality by 2050 or an indicative emission reduction of approximately 90% by 2040 within the EU (as proposed by the European Commission). To meet these goals an emission reduction speed of 7.3 megatons per year would be necessary. The reduction speed between 2018 and 2023 was high at 9 megatons CO2-eq/year, but, according to the projections, this will drop to a mere 3.8 megatons/year in the years towards 2035.

Global and EU targets for methane emissions, energy use and renewable energy also unlikely to be met

The Netherlands has joined the Global Methane Pledge, which means that it has to reduce its methane emissions by 30% in 2030 compared to 2020. In the Netherlands around 75% of methane emissions are in the agricultural sector. According to the PBL, the Netherlands’ actual emissions reduction will be around 18.5% based on current implemented policy measures (proposed and adopted), implying that the probability of meeting the target is lower than 5%. When scheduled policy measures are included (such as the aim for renewed manure derogation by farmers) the emission reduction would decline by around 3.5 percentage points according to the PBL, meaning that the chances of meeting the target will fall further.

Furthermore, the European Energy Efficiency Directive has set targets for primary and final energy use in the Netherlands. The target for final energy use is binding, the one for primary energy use indicative. The target for final energy use in the Netherlands is set at 1,609 petajoule in 2030. In 2023, the final energy use was 1,723 petajoule, but according to the PBL it will rise to 1,833 petajoule in 2025 (for instance because production in industry and horticulture will rise and households will use more gas as gas prices have declined). After 2025, final energy use will fall again due to energy savings measures, with an estimated use of 1,744 petajoule in 2030. According to the PBL this means that chances of meeting the EU goal are around 5%. Including scheduled policy measures (such as extra subsidies for isolation in industry and buildings and phasing out bad energy labels for buildings) final energy use could fall somewhat more (to around 1,710), raising the probability of meeting the EU target to around 10%.

Finally, the goals for renewable energy probably will also not be met according to the PBL. In 2023, 17% of energy use came from renewable sources, thus meeting the goal of 16% in 2023 (in line with the Energy Agreement of 2013). Last year, the European goal for renewable energy for the Netherlands was sharply raised from 27% in 2030, to 39% in 2030. Although the share of renewable energy is expected to continue to rise in the coming years, the necessary acceleration in the pace will probably not be realised. The PBL projects the share of 33.4% in 2020, which is significantly below the new target. Also, compared to last year’s projection, the estimate has fallen by 1-4 percentage points due to less offshore wind, fewer solar panels, fewer heat pumps, and less energy savings.

2030 targets also threatened by long implementation phase of new policy measures

The PBL has evaluated how much time has expired between certain policy decisions and their actual implementation during the past ten years. Changes to legislation can take multiple years and market parties need to have sufficient time to prepare for a new norm. For example, the green gas blending requirement announced in 2020 has been adjusted and, if quickly passed by the House of Representatives and the Senate, will only be implemented in 2026 at the earliest. For large investments, five to ten years is the standard. For example, the CO2-capture project Porthos has been in development since 2018, but is only likely to be operational by 2026. Pricing, however, can have an impact much faster. Changing existing taxation rules can already deliver within a year, whereas the implementation of brand new taxation measures does take a longer time. Consequently, policy measures that takes a long time to implement, will be unable to bridge the gap between binding targets and projected outcomes in the five years left until 2030.European emission target ESR within reach

On a positive note, the PBL estimates that the Netherlands is well on track to reach the European emission targets under the Effort Sharing Regulation (ESR) for sectors outside of the emissions trading system ETS1 for industry and electricity (based on a 48% emission reduction in 2030 compared to 2005). This cumulative goal provides an emission budget of 830 megaton for 2021-2030 for the sectors of built environment, mobility, and agriculture. In the projections, the Netherlands remains well below this ceiling with 781-819 megatons. This is partially due to a decrease in emissions due to COVID-19, higher energy prices, and growth in wind and solar energy in the last few years.

Conclusion

According to the projections by the PBL there is a high probability that the Netherlands misses its main EU climate objectives and targets for 2030. Considering that there are major ideological differences between the parties in the coalition about climate change and climate policy, it probably will be complicated to agree on the policies that would put the Netherlands back on track to meeting its targets, also because there tends to be a considerable time lag between policy making and actual policy implementation. Therefore, it is likely that the Netherlands will not be compliant with EU regulation, implying that the risk that the government will be subject to infringement procedures has increased.