ESG Economist - New Dutch government scales back climate ambitions

Although no new government has officially been appointed by the Dutch King yet, a right-wing coalition of election winner PVV (far-right), VVD (liberal centre-right) and newcomers the Farmer Citizen Movement (BBB, right) and New Social Contract (NSC, centre-right) seems to be on the cards. The parties have already presented their policy plans for the next four years (1). In this note we first discuss the current climate objectives and targets of the Netherlands, next we look at the main changes planned by the new coalition government and, finally, we assess what the consequences are for the path towards meeting the objectives and targets.

The likely new Dutch government has presented its main policy plans for the coming four years

It’s target for the net reduction of Greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions is set according to EU regulations at -55% in 2030 compared to 1990, which is less ambitious than the previous government …

…. and some policy changes will make achieving the target for 2030 as well as the path towards Net Zero in 2050 unlikely and more bumpy

The government needs to submit its final updated National Energy and Climate Plan (NECP) to the European Commission (EC) by end of June 2024 ….

…. which will probably be too soon to include the planned policy changes of the new coalition

That said, these policy changes probably will not be in compliance with EU regulation …

… as they probably will result in lower reduction of emissions of certain GHGs such as methane and nitrogen, while net emission from land use, land use change and forestry (LULUCF) will probably rise

What are the Netherlands’ current climate goals and policy plans?

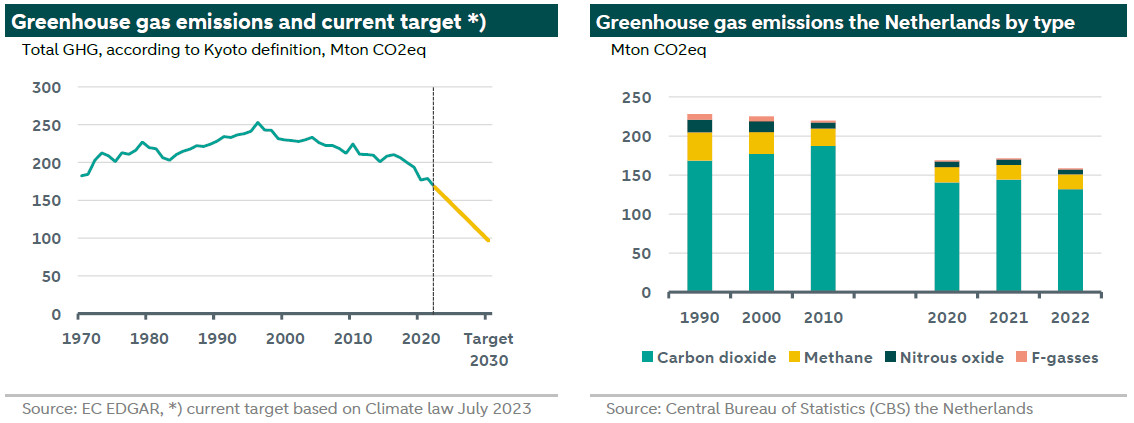

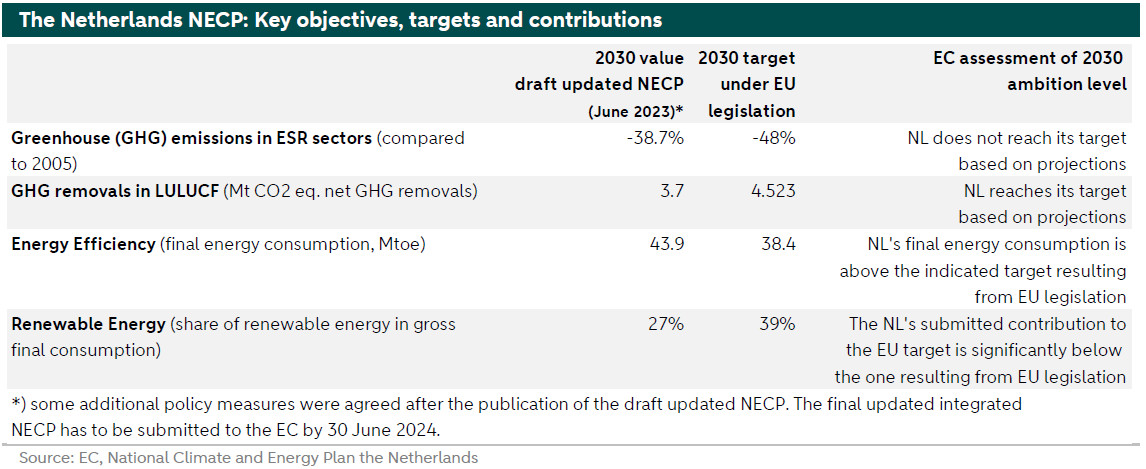

The Netherlands has agreed to the energy and climate objectives under the European Green Deal, the REPowerEU Plan and ‘Fit for 55’ legislative package. The country’s main policy objectives and targets are presented in its draft updated National Energy and Climate Plan (NECP), which was submitted to the European Commission (EC) in June 2023 (). In December 2023, the EC published its assessment of the Plan as well as a set of recommendations (), which are summarized in the table below. That said, since the publication of the draft updated NECP in June 2023, some policy changes have been agreed by Dutch parliament, for instance the target for the reduction of GHG emissions was increased to a least -55% net reduction in 2030 compared to 1990 (from -49% previously), and to net zero in 2050 (from -95% previously). On top of that, it was decided to build an extra buffer and aim at approximately a 60% (in fact 58%) reduction by 2030. The government has to submit its final updated integrated NECP to the EC by 30 June 2024, which makes it unlikely that the new coalition’s plans will be included. That said, the Commission’s assessment probably will be published around the end of the year and could, therefore, include some of the new coalition’s plans.

A separate independent analysis of the plans of the previous government (including the additional measures that were agreed in June 2023) was published by the PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency (‘Planbureau voor de Leefomgeving’) in November 2023 (). One of its main conclusions was that an emissions reduction in the range of 46-57% (2030 versus 1990) could be achieved but that parts of the climate plans had not been sufficiently been worked out. Also the PBL mentioned that it was essential that a quick start had to be made to the full implementation of all plans in order to meet the targets. The report by PBL does not take into account the fall of the Rutte IV government in July 2023, and the fact that certain policy proposals were declared controversial by the caretaker government (i.e. part of the climate plans were not implemented). Therefore, it seems likely that the PBL’s assessment of the emissions reductions would be less favourable today.

What will be the main changes by the new government?

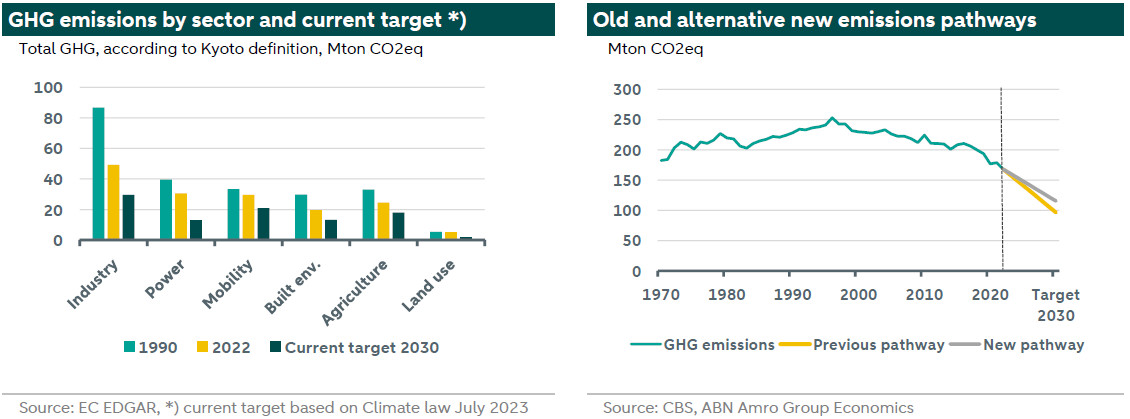

Some of the Netherlands’ climate goals will remain broadly intact according to the plans of the new coalition. For instance, the 2030 target for the reduction of GHG emissions has remained at 55% (compared to 1990 levels), although this no longer is a minimum reduction, and the extra buffer will be skipped. Also the plans to shut down all coal-fired power stations as of 2030 have remained and the EUR 35bn Climate Fund (for the financing of climate technology) will be maintained, although there will be some reductions in spending of around EUR 1.2bn in total (2). That said, some changes to the existing policy plans are on the cards, which seem to imply that the Netherlands will not meet the 55% reduction target.

Importantly, the coalition agreement contains several plans to support the agricultural sector and construction, which will have consequences for biodiversity and emittance of methane and nitrogen. For instance, there will be no forced expropriation of farms close to nature reserves, no further shrinkage of the livestock population and a reduction in the excise duty on diesel paid by farmers. Furthermore, new measures to solve the manure problem are needed. Dutch farmers are currently spreading more manure on land than is allowed under European rules and the new coalition aims at continuation of this exception to the rules (i.e. derogation). This would require renegotiating with the European Commission, which has not been successful after several attempts to date.

In addition there are some other policy plans and tax changes in the coalition agreement that could also have an impact on whether the climate goals will be met, such as ending subsidies on the purchase of EVs in 2025, raising the maximum speed limit on highways, extending a tax cut on gasoline, significantly extending the amount of land that is available for construction and giving priority to fishery when this would be in conflict with increasing the amount of windmills at sea. Also when deciding about land use for housing construction or building windmills on land, priority will be given to housing construction. The government also plans to cancel the hike in energy taxes for households and extra emission taxes for companies that were planned by the previous government and also wants to reduce energy tax payments by lower income households. Finally, the coalition wants to change the energy mix by opening two extra nuclear power plants in the Netherlands. Although this could lower GHG emissions the results will probably be felt only in the medium to longer term (see our earlier research note ESG Economist - How feasible are the Dutch plans for nuclear power? here).

What could be the longer-term consequences?

Commenting on the coalition agreement the Dutch independent research institute ‘Sociaal en Cultureel Planbureau’ (, in Dutch only) qualifies the new government’s climate plans as being reserved and at some points even withdrawing compared to the previous government’s plans. Indeed, we think that the main consequences of the new plans will be that emission reductions of the greenhouse gases methane and nitrogen will be lower during the next four years and that net emissions reductions in land use, land use change and forestry (LULUCF) will be lower as well. Moreover, the target of building an extra buffer in order to aim at 58% instead of 55% total GHG reduction in 2023 compared to 1990, has been removed. This means that achieving the 2030 target for total GHG emission reductions as well as the path towards Net Zero in 2050 has become less likely and more bumpy.

In order to assess the possible consequences of the new coalition’s policy plans for total GHG emissions we have constructed an alternative ‘what if’-scenario based on the emission reduction targets by sector as set by the previous government (see graph above) . If we assume that only around 25% of the targeted emissions reduction by agriculture will be achieved between 2022 and 2030 (which actually could be optimistic considering that the government has agreed to a lot of the policy demands of the Farmer Citizen Movement), around 50% of the reduction by construction will be achieved, and that there will be higher net emissions by LULUCF, total net GHG emissions will probably fall by around 50% in 2030 compared to 1990 (assuming that total reductions by the sectors industry, power and mobility remain on track to meet the 2030 targets).

To conclude, the plans of the new coalition government seem to imply that the Netherlands could miss some of its main EU climate objectives and targets for 2030. This means that the risk has increased that the government that takes office after the next general elections (due in 2028) would have to seriously step up climate policy measures again. Also the risk that the government will be subject to infringement procedures (in case it does not comply with the EU climate laws) seems to have increased. (see ).

(2) According to reports in the press, the far-right, climate sceptic PVV leader Geert Wilders admitted he had to give up almost all of its climate plans in order to reach agreement on other policy matters