US Watch - Tariffs are not the endgame

There is increasing noise on a ‘Mar-a-Lago accord,’ an idea outlined in a paper by CEA Chair, Stephan Miran. The accord is part of a grand plan to devalue the dollar, similar to the 1985 ‘Plaza Accord,’ that is envisioned to increase US manufacturing competitiveness, and revitalize the economy.

The framework of this plan uses tariffs and defence support as strategic tools in negotiations

The US’ business cycle stage, and changes in configuration of the global economy since 1985, make a successful repeat of the 1985 Plaza Accord unlikely, thought that may not deter the Trump administration

A statement of the Trump’s administration intent, and shifts in fiscal outlooks, both in the US and its major trading partners, have already pushed the dollar down but not enough to reduce the need for the accord

The overall plan is inflationary and suppresses growth.

In 1985, US officials met with G5 countries at the Plaza Hotel to negotiate a coordinated intervention to devalue the dollar. Over the last weeks, a so-called ‘Mar-a-Lago’ accord, to be negotiated at the President’s Florida resort rather than the Plaza, has been receiving significant attention. The accord is part of a grand plan to devalue the dollar and radically re-order global order and trade. This new view of trade focuses on distortions that lead to trade imbalances, and is set out in the work of, for instance, Pettis and Hogan (2024). These arguments are used in the Council of Economic Advisers Chair Stephen Miran’s piece ‘A user's guide to restructuring the global trading system,’ in which he sketches out what are, in his view, structural problems that the US is facing, and sets forth a number of policies that connect trade, financial flows and defense to alleviate them.

The Mar-a-Lago accord is therefore best understood in this wider context. The basic premise is that the dollar is overvalued because of its reserve currency status, which prevents the balancing of international trade. This overvaluation has supposedly hollowed out the US’s manufacturing and tradeable sectors. Tariffs are used to rebalance trade, draw more investment to the US and rebuild industrial capacity. However, the dollar will appreciate inevitably, undoing much of the work. The solution is a Mar-a-Lago accord, mirroring the 1985 Plaza accord, where countries would cooperate to weaken the dollar, whilst keeping the reserve-status of the dollar. Countries are unlikely to cooperate with this freely, and a combination of sticks and carrots is supposed to get them to agree. Countries could be divided into red, yellow and green zones, a view also Green will come inside the sphere of influence of the US, they can cut deals on tariffs, get military support, but have to cooperate with the US on its geo-economic goals, including the weakening of the dollar. Red countries are clearly outside the influence and can expect substantial tariffs. Yellow ones may cut a deal in some of these aspects.

In the following, we set out and reflect on this new view on trade. We summarize how Miran’s view on the global economy is shaped by this framework, and to what extent the statements put forth are grounded in fact, or at least mainstream economics. We next focus on the Mar-a-Lago accord, what it would entail, where the challenges lie, and how likely of a scenario this is. We finally discuss how recent developments in policy across the globe may limit the need for the accord and its associated risks.

Miran’s view on the global economy

The Miran piece is fundamentally based on a new view on trade that has been circulating in policy circles, which has been set out in, amongst others, Pettis and Hogan (2024). The first pillar of the theory states that trade should be more or less balanced, at least at the country by country level. Large trade deficits exist because of government policies, particularly in surplus countries, and these policies hurt deficit countries. Tariffs should be used to address this issue. This view is not a great description of the world in 2025, or even most of history. Many countries have run high trade deficits, or more aptly current account deficits, for extended periods of time without any problem, especially in the absence of government policies on in particular capital flows. Now there are substantial capital flows, and private flows dominate the official flows. Capital flows as a reserve asset may be part of the story, but certainly not the complete story. Part of the rising popularity in this theory perhaps lies in China, whose current account surplus can partially be attributed to state decision in the context of restricted capital flows.

From the Miran perspective, the main argument is the following. The dollar is overvalued because of its reserve status. The US is ‘forced’ to run a deficit because foreigners want dollars as reserve assets. These ideas are related to the Triffin (1960) view of the world, where a reserve currency forces the country to have current account deficits, until the point where it has accumulated such debt that it loses its status. This overvaluation hurts US competitiveness, harming manufacturing and tradeable sectors. Competitiveness may be restored through tariffs and currency policy, or a combination thereof. Tariffs play a dual role of industrial policy, and leverage in negotiations regarding currency policy, where Miran explicitly also suggests the US’ defense umbrella may give the US the necessary leverage.

The ultimate goal is to devalue the dollar, whilst preserving reserve currency status. Not an easy feat, especially considering the upward pressure tariffs put on the dollar. The solution is the Mar-a-Lago Accord; countries should sell their dollars and short-term treasuries and substantially increase the duration of remaining holdings. This limits the rise in long-term yields and keeps the dollar in reserve books and therefore solidifies its reserve status for the long term. In order to convince countries to sign up, tariffs, that were recently pushed on them, could be reduced or removed, and the signing countries may count on the US’ defense support.

Miran acknowledges the difficulty of implementing the proposal. Currency policies like these haven’t been implemented at this scale in decades. He writes: “There is a path by which these policies can be implemented without material adverse consequences, but it is narrow.” The path succeeding largely relies on countries ultimately following suit. He does not discuss what happens to the US if the plan fails, nor what happens if countries retaliate, like they are doing, nor what happens if countries are pressured to sign on to a Mar-a-Lago accord, but they don’t.

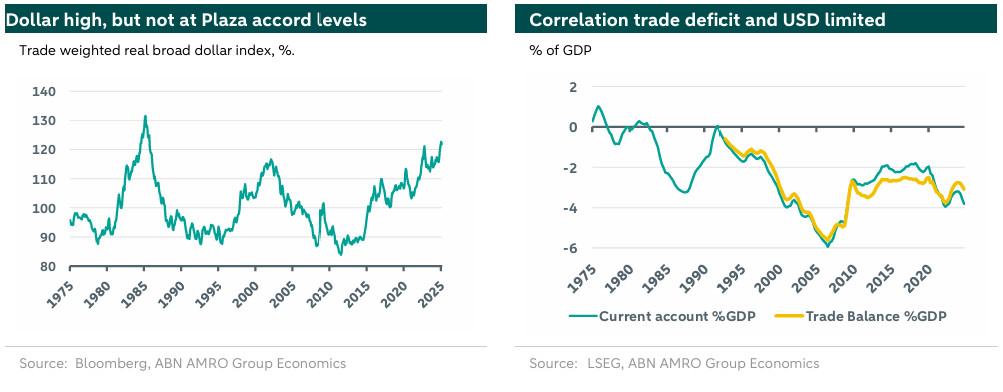

Is the dollar actually overvalued? It’s valuable, but not as valuable as it was in the 1980s when the Plaza Accord was signed, see the chart below. Correcting for unit labour costs, to see its impact on competitiveness, the value has overall decreased since the early 2000s. It does not necessarily have its current value because of its reserve status. The value of the dollar has seen a wide range over the past decades, and its reserve status hasn’t changed. There are clearly other factors, such as the US government deficit and high levels of private demand that play a role, with domestic supply being unable to keep up. Still, its value would likely be lower if the dollar was not the world’s reserve currency. It has that role because of the properties of the US economy; it is the largest economy, it has good rule of law, respect for institutions, decent and predictable macro policies. Because of these properties, and the fact that the US has the deepest most open liquid capital markets in the world, the rest of the world likes to hold dollars, which brings in capital, and pushes up the dollar. If the dollar truly were overvalued relative to, for instance, the euro, private capital flows could move from the US to Europe, but over the past decades that hasn’t happened.

Is having a reserve currency costly? Miran implies that the dollar’s role is bad for the US, in contrast to the exorbitant privilege that is usually attributed to it. Academic consensus appears to be that the dollar’s role is a net plus, though not exorbitant. The US gets marginally lower rates, it is shielded from exchange rate risk, and it can use the dollar for geopolitical leverage via sanctions. Manufacturers and the tradeable sector may be hurt by the overvaluation, because exports are less competitive, but at the same time they can buy imported components and intermediate goods cheaper. Homeowners benefit from lower rates and investors benefit from lower cost of capital.

Is the current account unbalanced? There’s no reason for current account balance to be zero. Some countries are going to have deficits for structural reasons, such as, for instance, demographics, energy endowments and strength of institutions. The IMF has a country level estimate of what the current account balance should be, based on such factors, and estimates it at a 2% deficit for the US. The US’ deficit is pushing 4% of GDP, which is substantially higher, but this is not necessarily caused by the strong dollar, see chart below. It can more directly be tied to both public and private sector spending; the US budget deficit for 2024 is above 6%, and the private savings rate is low.

Is deindustrialization even a problem? Manufacturing is important. Industrial policy has long been regarded as mostly inefficient from a growth perspective. More recently, there’s an increasing case to be made for industrial policy to support strategic sectors, i.e. defence, semiconductors and other important goods, with sovereignty and agency coming at the cost of some efficiency. Indeed, Miran warns about the risks of depending on foreign suppliers, especially from China, for critical products such as steel, aluminium, semiconductors, and pharmaceutical products. The product list is remarkably similar to the targeted tariffs that we’ve seen threatened and implemented over the past months. There is also a widespread view that manufacturing jobs are good jobs. This is also no longer really true; hourly wages for non-supervisory workers in manufacturing are lower than in the rest of the private sector. Productivity in services is generally higher, and this is where the US creates a lot of value and soft power, with big tech a prime example.

Will tariffs help the trade deficit? Even if it limits imports, the deficit will tend to increase in other ways. Tariffs tend to lead to a stronger dollar, cutting into exports. Tariffs also tend to lead to retaliation, again, cutting into exports. Tariffs are different form a currency devaluation in that aspect. Devaluations contract imports and expands exports as you’re more competitive, while tariffs restrict imports but also reduces exports through exchange rate appreciation. This brings us to the Mar-a-Lago accord.

The Mar-a-Lago accord

Like the Plaza Accord in 1985, the idea is for the US to come together with its major trading partners and holders of dollar reserves, to negotiate a coordinated devaluation of the dollar. Back in 1985, the major players were the US, France, Germany, Japan and the UK. They settled on a coordinated intervention in currency markets to depreciate the dollar relative to other major currencies. The countries collectively sold dollars and buy their own currencies, and aligned fiscal policy, which led to a depreciation of the dollar in subsequent years. The US trade deficit did actually decrease, but it led to mild inflationary pressures. For Japan, the yen appreciated significantly, which led to a period of economic challenges including asset bubbles and eventually a recession in the 1990s. Other countries like Germany also saw their currencies appreciate, which impacted competitiveness, but helped curb inflationary pressures.

Miran sees the euro, renminbi, and to a lesser extent the yen as the most important currencies in the current environment, but acknowledges that especially Europe and China are unlikely to agree to a similar accord. Both the Eurozone and China are not in a position to actively reduce their competitiveness. Miran proposes a multilateral approach where these countries might be persuaded to sign such an accord in exchange for a reduction of tariffs, which the Trump administration is currently in the process of applying, and defence support, which the Trump administration is currently withdrawing. To mitigate rising interest rates, countries should sell their dollars and short-term treasuries, and substantially increase the duration of remaining holdings, ideally with ‘century bonds.’Alternatively, Miran suggests a unilateral approach may be used, which might force foreign reserve managers to reduce their holdings by imposing a user fee on foreign official holdings of US treasuries. Alternatively, the US government could increase the size of its Exchange Stabilisation fund and buy foreign debt, sell its gold reserves and buy foreign debt, or, the Fed could be asked to print dollars to buy foreign debt. He even talks down inflationary impact of especially that last option.

Who are likely to be the Mar-a-Lago counterparties? It will be difficult to recreate the plaza accord forty years later. The world of capital and trade flows now looks remarkably different. Back then, the G5 countries that took part in the Plaza Accord accounted for a significant part of trade and capital, but this is no longer the case. Reserves are far more spread out, overall FX flows are much larger, and there’s a much greater role for private sector money. The chart below gives an overview of the current distribution of Treasuries. Miran explicitly calls out the major alternative currencies, the euro and renminbi, but in terms of foreign reserves, they might have little sway. China’s holdings may be somewhat due to some assets being moved to securities depositaries in e.g. Belgium and Luxemburg, overstating EU holdings. Most of remaining reserves are in the hand of other countries in south-east Asia, particularly Japan, with also prominent roles for the UK and Switzerland. In terms of trade balance, the ultimate goal, the major counterparties are China, Germany, Mexico and Vietnam.

Does the US have enough leverage for a multilateral agreement? It seems increasingly unlikely. The US would pressure countries by a combination of tariffs and defence support/withdrawal. Let’s start with the latter. Over the past month, the US has lost considerable credibility in terms of being willing to provide defence support in the first place, withdrawing support for Ukraine, and threatening to leave NATO. Europe is clearly positioning itself to no longer be dependent on the US, although this will take time. China will never be under the US’ defence umbrella. Other trading partners or reserve holders, such as Mexico, do not currently have a defence alliance or are unlikely to have a lot of faith in such a commitment. Tariffs have likely lost some of their initial power as well. The US’s negotiating credibly has taken a serious beating. The fact that Trump reneged on USMCA will make countries think twice about agreeing a deal with the US. Moreover, Trump has used them to deal with many objectives, there have been postponements and cancellations. After April 2nd, the scope is likely to be so wide that the damage to the US is of the same, or greater, magnitude than all but the worst-hit trading partners, further reducing their leverage.

Is unilateral action then likely? Given the above, unilateral policy is arguably more likely to be implementable, although it is probably too bold, even for this administration. One could force the swap of treasuries to century bonds, but that would likely be characterised as a default, with rating downgrades as a result. The Exchange Stabilisation fund in its current state is far too small to do anything, and an independent Fed will certainly not go along. The US has the world’s largest gold reserve, but has it officially valued at just $42 per ounce since 1973. Using the current value would push the value of the reserves up to over three-quarters of a trillion dollars. Revaluing the gold holdings has also been mentioned in the context of the Sovereign Wealth Fund (SWF) that Trump ordered to be created, but its role in a Mar-a-Lago accord is unspecified. Still, this SWF could also be used to purchase foreign debt at large scale, although Trump has proposed to invest in domestic assets. Overall, unilateral action will certainly help in devaluing the dollar, but predominantly in indirect ways, through damage to its reputation.

Will the dollar keep reserve status? As stated above, the US dollar has its reserve status for several reasons. Current developments are rapidly leading to the erosion of a number of them, and even just an attempt at a Mar-a-Lago accord would put further pressure on that status. At the same time, the US still has the deepest most open liquid capital markets in the world, and there does not appear to be a real alternative, see the chart on the right below. Euro-denominated debt is the second most-held, but a lack of an integrated capital market and Eurobonds makes this difficult in the short run. BRICS have periodically raised the idea of working together on a joint reserve currency, but with no significant progress. The IMF’s Special Drawing Right (SDR) have some theoretical advantages, but many practical challenges remain. There have been predictions of the dollar’s imminent decline for many decades, and the US has abused its privilege before. The cumulative advantage that has been built over decades is really hard to unwind and is unlikely to be lost in the short-term.

What happens to the economy if the devaluation works? At the time of the Plaza Accord, the economy was still recovering from the early 1980s recession and growth was strong. The Fed was not yet targeting 2%, but at 3.5% y/y PCE inflation was well below the average rate between 1960-1990. Moreover, the unemployment rate stood at over 7%, lowering to 5% in the ensuing years, which academic evidence suggests is least partially attributable to the accord, with some exporting sectors experiencing increased employment. The slack in the economy limited the inflationary impact, although it still increased somewhat. The current situation is different, with the unemployment rate at a low 4.1% and inflation already above target. If the trade balance improves when the economy is at full capacity, components of domestic demand (household consumption and business investment) are crowded out. The depreciation increases the cost of imported goods and services, further contributing to inflation. For consumers, this means higher prices on imported goods and potentially reduced purchasing power. Domestic producers will likely also raise their prices, being protected by tariffs to outside competition. The Fed may need to intervene by tightening monetary policy to curb inflation and stabilize the currency. The balance between stimulating growth and controlling inflation becomes a delicate challenge in such conditions.

What does orthodox economic theory say about how a government can simultaneously decrease the trade deficit and depreciate the dollar? The standard approach would be fiscal tightening; cut spending and responsibly raise taxes. As domestic demand for goods decreases, imports decline. Higher taxes can encourage higher savings rates, which reduces the need for foreign capital to finance investments, improving the current account deficit. Lower demand is also likely to lead to lower inflation, which may lower Fed interest rates, which in turn depreciates the dollar. This improves the competitiveness of US exporters, boosting exports, leading to further reductions in the current account deficit.

A confluence of circumstance

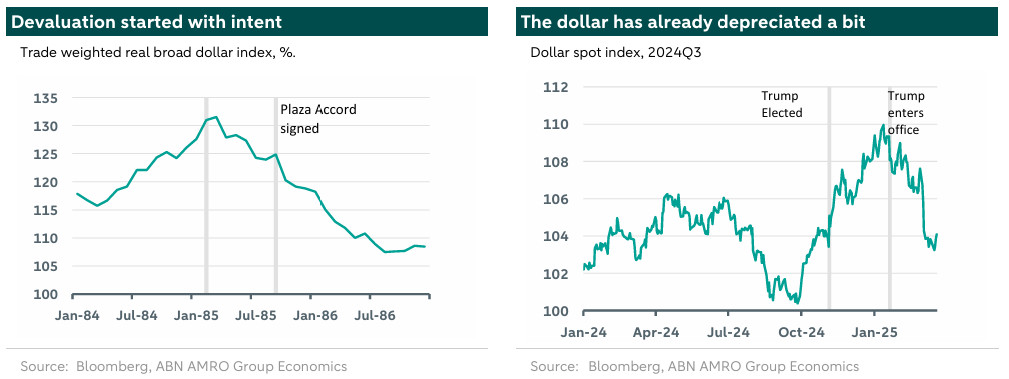

The Plaza Accord was successful in reducing the value of the dollar. Two aspects in this are worth mentioning. The first, is that the dollar already started depreciating long before the Plaza Accord was actually signed. Rather, it started depreciating when the new Treasury secretary Brown entered office, of whom it was known that a policy goal was to explicitly weaken the dollar. Market expectations play an important role, and can do a lot even in the absence of formal policy. Think of Draghi’s famous ‘Whatever it takes’ speech. We see the change in the dollar’s directionality between the election and the period after his inauguration when the policy talk of dollar devaluation increased.

Second, the Plaza accord was successful because it was a coordinated effort, not just in buying and selling foreign reserves, but also in terms of policy. You can move reserves, but the overall economic cycles need to align such that the equilibrium exchange rate is close to the targeted exchange rate. What do these lessons teach us about the current situation?

On the cyclical front, the US economy looks set to weaken substantially, to a large extent attributable to Trump policy. Recession fears are rising because of tariffs. This has generally led to a decrease in long-term yields, despite upside inflation risks from tariffs. Moreover, in the administrations mind, DOGE and tariff revenue, would lead to a reduction in the government deficit, but tax cuts may more than undo that.

Meanwhile, Europe is in fiscal expansion mode, predominantly increasing their defense spending to fill the gap the US is leaving. China has been stepping up fiscal support to deal with both domestic headwinds and tariffs. This recently led to higher bond yields and some appreciation of their currency relative to the dollar. The movement we’ve seen until now is however nothing compared to the depreciation we saw following the Plaza Accord.

Although tariffs may lead to a stronger dollar in the short-run, if Trump keeps the tariffs perpetually, this will likely lead to structurally lower growth, and the longer-term equilibrium value of the dollar is likely less than it would otherwise have been. The structural erosion of institutions, and the US’s reneging on its dominant position in the world theatre, weakens the dollar’s reserve position. While in the short-run the dollar is probably safe due to lack of alternatives, in the medium-term, the pressure will build for its dominance to end, and with that, part of its value. What does this mean for the rest of the policy outlook? The rebuilding of trade, and revitalization of manufacturing is clearly a policy goal of the Trump administration. Industrial policy, particular tariffs, will remain a big part of that. The dollar would have to depreciate substantially more as to remove the reasoning for a Mar-a-Lago accord, so despite little chance of success, they may still try, with all the adverse geopolitical effects that entails. Empirical analysis on this new view on trade is limited, and what evidence there is, finds little to no support the hypotheses. In the near term however, the overall package would be inflationary and reduce growth.