US: Recession in all but name?

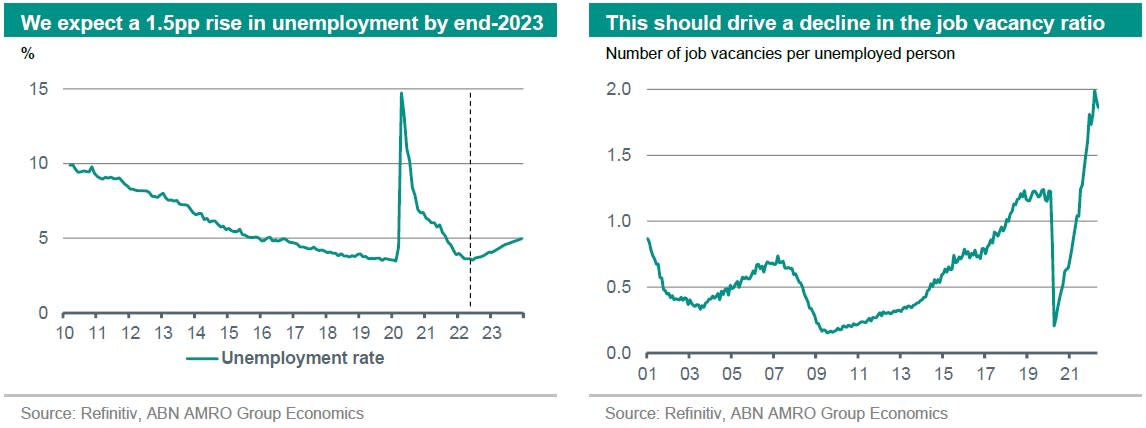

A volatile supply side could mean the US just about escapes a technical recession, but underlying growth is likely to weaken significantly on the back of a jump in interest rates. This is likely to raise the unemployment rate by 1.5pp by the end of 2023, helping to cool inflation.

This is part of the Global Monthly, see here

Notwithstanding the significant fall in the June flash PMIs this week, demand indicators so far in Q2 have been very strong in the US, with private consumption data showing continued above-trend demand for goods, and services recovering further back towards trend. Alongside an improvement in net exports, we expect this to drive a 3.8% annualised rise in GDP in Q2, following the 1.5% contraction in Q1. As we move into the second half of the year, however, we expect the growth environment to deteriorate. The deepening inflation hit to real incomes, combined with the tightening effect of higher interest rates – which is already hitting many households via higher mortgage payments and reduced net wealth via stock market declines – is likely to lead to broadly stagnant consumption (i.e. near zero growth) over the coming quarters. Fixed investment will be supported in the near-term by catch-up from the pandemic, as the supply-side continues to recover, but we expect investment to subsequently contract in the first half of next year. The headline growth picture is complicated by the supply-side disruptions and pandemic recovery distortions, and as such headline GDP growth is likely to continue to be volatile over the next few quarters on the back of swings in inventories and net exports. However, underlying demand is expected to weaken significantly this year and particularly as we move into 2023.

The projected weakening in demand is likely to lead to some rise in unemployment, probably beginning in late Q3 this year and picking up pace in Q4/Q1 next year. Our new base case is that unemployment peaks at c.5% in early 2024 from 3.6% as of May. This, combined with a significant fall in job vacancies, should bring the unemployed-job vacancy ratio down to below 1 by late next year from around 2 at present. This ratio has become a key metric for the Fed, as it reflects the significant supply-demand imbalance in the labour market that is risking a de-anchoring of inflation expectations. Indeed, on inflation itself, we have made a further upward revision to our 2022 annual average forecast to 9.0% y/y from 8.0% previously, and expect more of this strength to carry over into 2023, with inflation expected to average 4.6% (previously 4.1%). The Fed’s key focus is on month-on-month readings, and here we expect readings to remain far above levels consistent with the Fed’s 2% target for much of the remainder of 2022. Thereafter, the weaker labour market should drive a sufficient cooling in inflation by Q2 2023 to convince the FOMC that it has tightened policy enough.

While we had already made a significant upgrade to our expectation for Fed rate hikes prior to the June FOMC meeting, with the upper bound of the Fed funds rate now expected to peak at 4% in February (up from our previous 2.75% expectation), the supersized 75bp hike in June combined with Powell’s hawkish signalling led us to frontload some of this tightening. We now expect one further 75bp hike in July, with this followed by 50bp moves in September and November, and 25bp hikes in December and February. The risks to rates continue to be to the upside, as are the risks to the inflation outlook itself.