Global Monthly - Will the European economy survive a Russian gas cut-off?

We expect a significantly steeper rise in interest rates, and stagnant growth over the coming year. Against this backdrop, the threat of an abrupt cut in Russian gas supplies to Europe is beginning to crystalise, raising the prospect of a potentially deep recession. We describe how a gas cut-off might cascade through the economy, and the policymaker response.

Another supply shock is hitting Europe, as the economy already shows signs of slowing

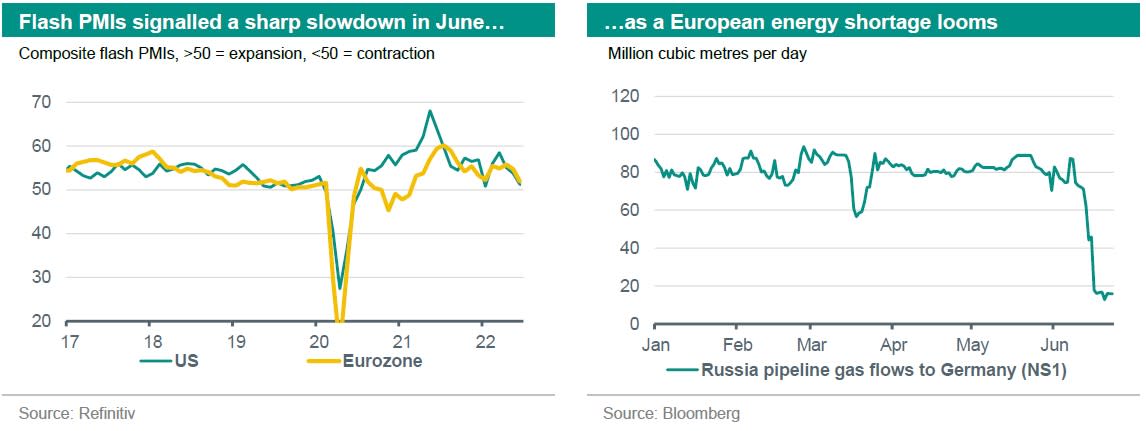

The risk of recession has grown further over the past month, as economies have shown increasing signs of slowing, and expectations for central bank policy tightening have increased sharply on the back of broadening inflation risks. On Thursday, the June flash PMIs indicated a sharp slowdown in growth on both sides of the Atlantic, driven by forward-looking indicators such as new orders and business expectations over future prospects. Against this backdrop, in the last few days it has become increasingly clear that yet another supply shock is likely to hit the European economy over the coming year. Russia appears to be cutting gas supplies to Europe abruptly ahead of the more gradual weaning off of Russian energy being pursued by European governments thus far. In this month’s Global View we focus on the most likely future scenario for a gas stoppage that is already underway, and the economic implications. Before this risk began to crystalise over the past week, we had already made significant downgrades to our growth forecasts, with stagnation expected on both sides of the Atlantic making up our new base case for 2023. These downgrades come on the back of the massive hit to real incomes from high inflation – which is weighing heavily on consumption – and the sharp rises in interest rates we now expect over the coming year. However, an abrupt stop in Russian gas supplies would mean an even darker scenario – with potentially a deep recession in the eurozone and UK economies over the coming year.

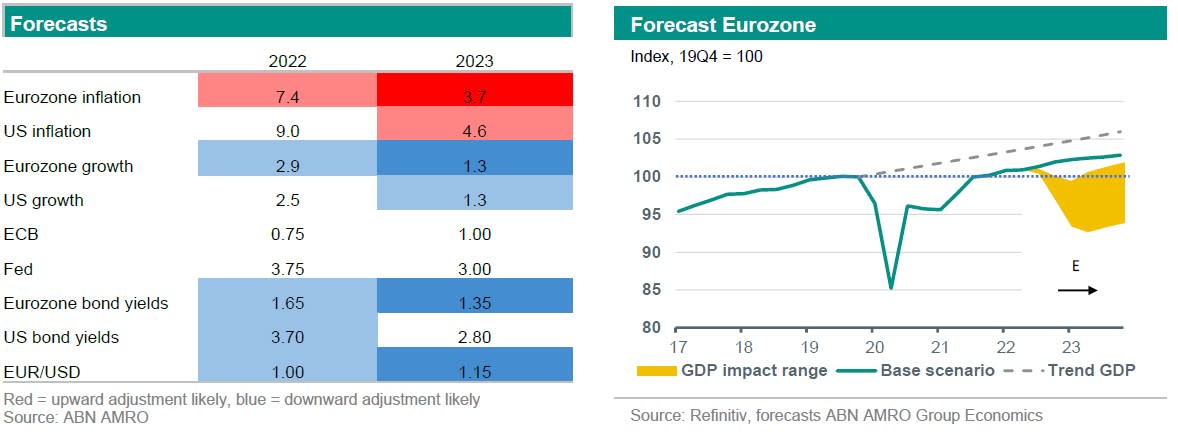

The renewed supply bottlenecks a Russian gas stoppage would lead to are taking place against a background of a global economy that is facing severe headwinds from stubbornly high and broadening inflation and a global monetary tightening in response. Therefore, we start with the macro and rates baseline scenario to which we have already made significant adjustments since last month (see table below). Subsequently we will sketch out a possible path of the gas stoppage and its implications for the European economy. While this analysis is focused on the eurozone, given the UK’s integration into the European gas market the effects would be similar to that of the eurozone. As these developments are still very fresh and fluid, for now we give only a broad indication of the adjustments we are likely make to our forecasts. We will make more concrete adjustments to our base case as the way forward becomes clearer.

Our new baseline on inflation and global tightening

We have raised our forecast for rate hikes for both the Fed and the ECB. In the US we are seeing persistently strong demand despite elevated inflation. In addition, we observe a more hawkish reaction function amongst FOMC members. As such, we now expect the upper bound of the Fed’s target range to reach 4% by early 2023, with the risk to this forecast still tilted to the upside. Also for the ECB we have made a significant change to our view. After the likely 25bp hike in July, we expect a 50bp move in September, followed by 25bp steps until the deposit rate reaches 1% in February. We previously expected just two 25bp hikes in July and September. The main reasons for our ECB view change are threefold: First, inflation has continued to accelerate beyond expectations. Even though the evidence suggests that the vast majority is driven by supply-side imported inflation and to some extent post-lockdown catch up, it still creates challenges for the ECB. Most importantly, there is a concern that continued high rates of inflation will dislodge inflation expectations, especially given the possibility that supply-side shocks will be more persistent. Second, even though there is not too much that the ECB can do about supply-side driven inflation, there is a general sense that a very accommodative monetary stance is no longer appropriate. The ECB therefore wants to normalise policy or take it back to more neutral levels. While there is a lot of uncertainty about where neutral is, there is broad agreement in the Council that it is much higher than current levels and also above zero percent. Third, the upward revision to our profile for the Fed’s target range means that there would be additional downward pressure on the euro if the ECB does not continue to raise interest rates over the next few months. A weaker currency is undesirable in this environment, as it would add to imported inflation. Indeed, in contrast to the last few years, we now live in a world of ‘reverse currency wars’. To be clear, the ECB will not be able to prevent the euro from falling, but it can reduce the extent of the decline. Both the Fed’s and the ECB’s target range peaks are seen in February 2023. As a result of significantly tighter monetary policy, we have also downgraded our growth expectations for both the US and the eurozone for next year, and made adjustments to our bond yield and FX forecasts, given our projection for more rate hikes. Against this background of already significant global turbulence, the impact of a gas stoppage from Russia to Europe is both hard to quantify and potentially highly impactful. In this Monthly we mainly focus on the channels of impact.

The likely path for Putin’s gas stoppage

Five European countries are currently fully cut off from Russian gas imports. These are Poland, Finland, the Netherlands, Bulgaria and Denmark. Export cuts towards Germany and Italy are also happening: the supply through NordStream1 for Germany is down by 60% and Italy faces a supply decrease of 50%. The total drop in Russian gas exports towards Europe is around 60 bcm at the moment. Reduced gas imports make the filling of European gas inventories to around 80% before October (the EU goal) challenging. At the moment, European gas are around 55% filled (of which Germany: 59%, the Netherlands: 49%, Italy: 55%, France: 59% and Spain: 71%). Portugal and Poland already have completely full inventories. Even with inventories filled, however, a cold winter may mean that energy security is at stake.Assessing the supply shockIn terms of how far the gas cutoff might evolve, we see three possible scenarios:

The situation will remain as it is (a loss of -60 bcm),

Russian exports towards Europe will drop even further to 2/3rd of the 2021 imports (-100 bcm), (Base case)

We see a full stop of further Russian gas exports towards Europe (-155 bcm).

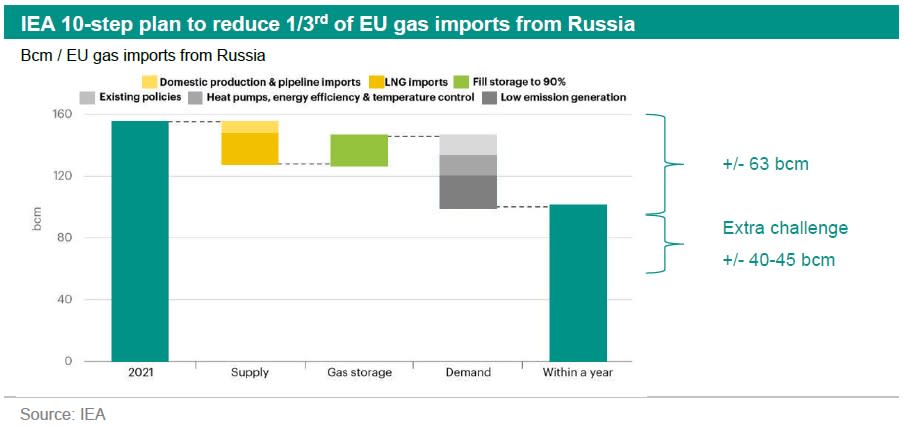

The first scenario would basically imply that implementing the 10-steps of reducing gas dependency as published by the IEA would suffice in dealing with the reduced gas supply from Russia. This is a combination of LNG diversification, pipeline diversification, bioenergy, energy efficiency and an increased usage of heat pumps and wind/solar energy. A scenario that we deem very challenging but feasible without much additional economic damage.

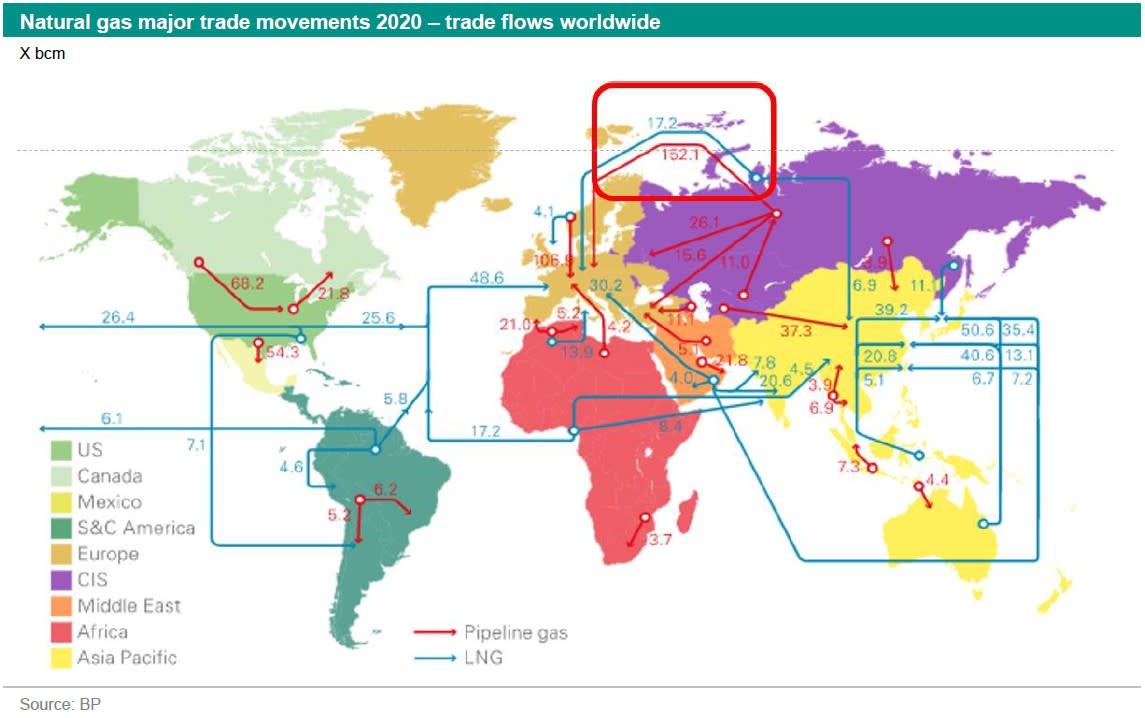

Scenario 2, a decline of 2/3rd of Russian gas exports, seems most likely. This would push Europe much further into a serious energy crisis. It means shortages, depending on (weather-related) demand, in combination with higher energy prices (gas, coal, oil, carbon, power) and fewer substitution options given the intrinsic rigidity of the gas infrastructure and the ongoing global quest for LNG now that pipeline gas becomes unavailable.From a Russian perspective, leaving 1/3rd of exports in place would already create shortages and economic harm in the EU but also push up prices and as such still generate a high profit (even though export volumes are lower). While most of Russia’s exports to Europe are under long-term contracts at cheaper prices, much of it is not, and some of the gas that is no longer exported to Europe can be diverted to Asia via LNG shipments. The 20 bcm challengeIn this 2/3 reduction scenario, the first 60 bcm of gas reduction (which we are currently facing) can be seen as achievable according to the 10 step plan by the International Energy Agency .

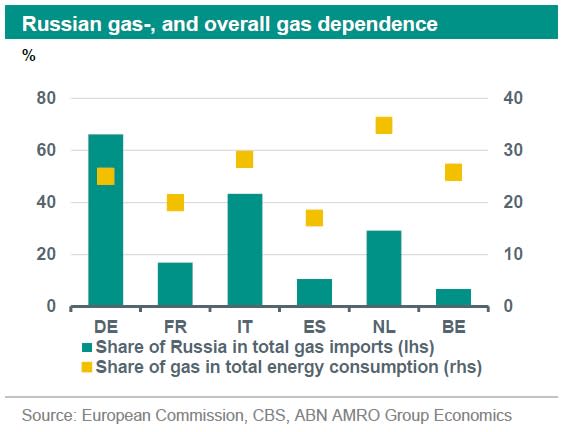

A 2/3rd gas supply reduction would mean that of the 100 bcm gas that is currently still being imported, another 40-45 bcm drop in Russian gas exports towards Europe will follow in the coming months. The recent announcements of reopened coal fired power plants to enable a gas-to-coal switch could roughly tackle 22 bcm (of which 25% is in the Netherlands and Germany). Assuming that energy savings in the residential sector will be modest in the short term (possible 5 bcm on top of the already assumed energy savings in the IEA plan), the main burden will fall on industry. This implies a 15-20% drop in consumption by the industry sector (20 bcm).No gas from Russia at all In case of a full gas stoppage (scenario 3), Europe will have to deal with an additional 50 bcm shortfall (on top of the challenges of scenario 2) through a combination of demand reduction in industry, but also somewhat in the residential sector or even in power generation. This would create serious problems and shortages. See the Box below for a comparison of various studies done on the economic impact of such a scenario for the German economy. All scenarios will trigger gas prices to remain high for longer. The shortages in the market would partly be countered by demand destruction, but tight market conditions will likely remain for the coming years. The gas-to-coal switch also adds upward price pressure to coal and carbon allowances, and would not trigger much relief for gas prices as the focus will remain on inventory building.

Economic Impact assessment

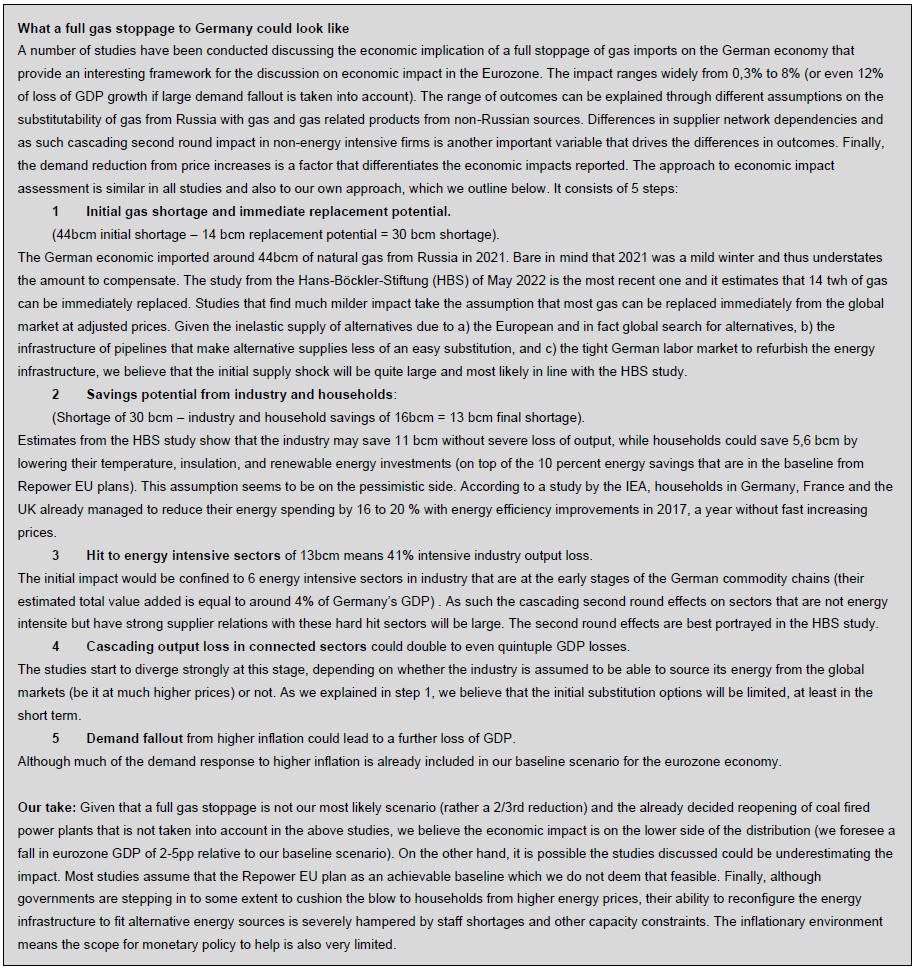

The flowchart below captures the main channels of economic impact that a severe additional supply reduction of Russian gas has on the economy. The initial reduction of gas supplied will at first be mitigated as much as possible through sourcing from different geographies and fuel substitution. Energy efficiency improvements would also be maximized. Whatever shortfall remains after mitigation and substitution is the final supply shock that causes economic damage. The supply shock triggers two initial effects: energy prices jump and industry energy use will be rationed by government regulation to protect households and essential sectors’ energy consumption. Energy intensive sectors which are considered relatively less relevant to domestic consumption will be closed first.

The price shock in itself could also render some business models obsolete as the margin squeeze triggers losses and ultimately bankruptcies. The direct effect from industry stoppages is output loss, but also indirectly these output losses cascade even to non-energy intensive sectors via supply chain linkages. The effects put yet further upward push on prices, uncertainty and risk premia. Inflation erodes households disposable income and, depending on consumers’ ability and willingness to dip into their savings, this will weigh consumption and economic growth. Uncertainty will weigh on investment which also affects medium term growth. Supply bottlenecks can withstand a lot of turmoil, but when confidence erodes, production networks can face serious distortions that take a long time to rebalance.

Eurozone

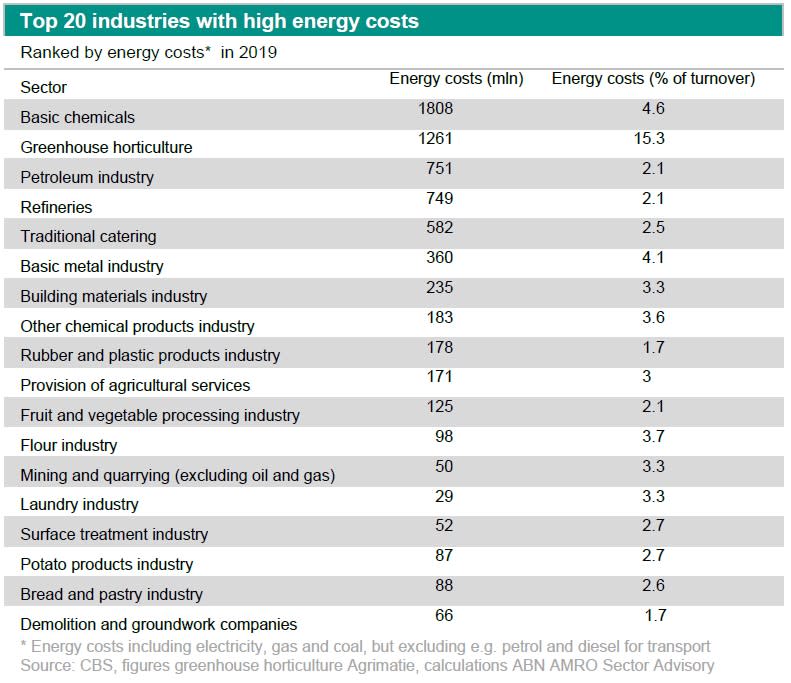

We have already lowered our growth estimates for the eurozone significantly since the start of the war in Ukraine. The jump in energy and food commodity prices and its impact on final domestic demand has been the major factor behind the downward revisions. The cut to GDP growth forecasts in 2022 and 2023 totals more than 2 percentage points so far. The potential impact of an abrupt end of Russian gas exports to Europe is not yet in our baseline scenario. Such a scenario would hit Germany and Italy particularly hard, as they are the two big-6 eurozone countries that are most dependent on gas imports from Russia. Both Germany and Italy import almost all their gas needs, with Russia having a share of roughly 65% and 40%, respectively, in total gas imports before the start of the war in Ukraine (compared to, for instance around 17% for France). The German and Italian governments have already presented plans to reduce their dependency on gas imports from Russia (amongst others by importing more from other destinations, such as several African countries, and by restarting coal-fired power stations), but each have said that this will take some time and that full energy independence from Russia would likely not be achievable before the second half of next year at the earliest. The Italian and German Energy and Economics Ministers have announced that the implementation of legal measures to save energy are a real possibility in the next few months. According to reports in the German press, the Federal Energy Agency has formulated a set of criteria by which decisions should be taken in the event of a gas emergency and potential shut downs in gas supply to the industrial sector. These include, the size of the plant and its energy use, the necessary lead time for gas procurement reduction or an orderly shutdown of the production facilities, the expected economic and business damage, the cost and duration of restarting after a gas supply reduction and the importance of the product to the general public. Besides plans to limit gas usage (reports in the Italian press for instance mention plans to limit air conditioning in most public buildings to a minimum of 25 degrees Celsius this summer) Italy has also recommended that European Union member states put a limit on the price of gas imports from Russia to help curb inflation and the economic consequences in the bloc. Indeed the European Commission has also included the option of an administrative price cap on gas at the EU level in a set of short-term measures to tackle high energy prices and address possible supply disruptions from Russia (see ). Such a EU initiative could ease the burden for individual countries. All in all, a disruption in gas supply in line with scenario 2, would imply a 20-25% drop in gas consumption by the eurozone industry sector (around 20 bcm). Such a drop would probably reduce GDP growth by around 3.5% and result in a deep recession in the eurozone economy. Unless there will be a common EU initiative for redistribution of gas and financial compensation, Germany and Italy would probably be hit relatively hard. Energy solidarity within the EU might cushion the economic impact, however in our current estimations we are not taking these into account.

The Dutch economy

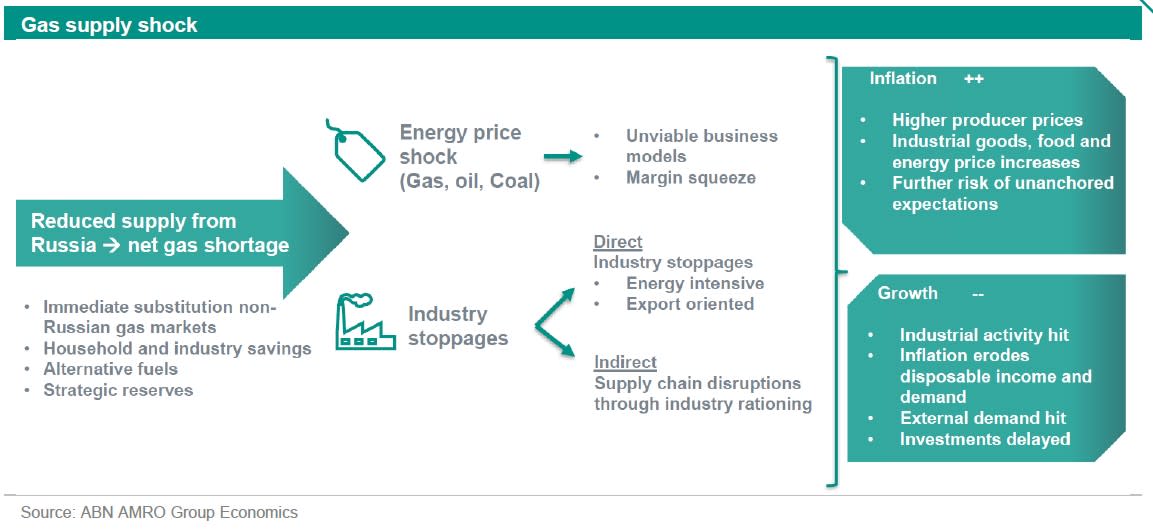

The Dutch economy is less dependent on Russian gas than the eurozone average. That said, current inventory levels (48%) suggest shortages are likely this winter, and gas makes up a large share of total energy consumption (34%). Therefore the impact off a Russian gas cut-off on the Dutch economy is as much linked to the price effect of the gas shortage as it is the effect that industry stoppages would have on activity. The price effect would make many business models in energy-intensive sectors such as fisheries and horticulture to become obsolete. But further price rises would lead to even more problems. They would affect a broader share of the business economy compared to recent energy price shocks as the gas-to-coal shift and substitution of gas to other sources of energy will push up prices in a electricity and oil markets as well. Industrial sectors that have the highest energy costs as a share of revenue would bear the brunt (chemicals, paper manufacturing, metals – see table below for gas usage as % of revenues).

Dutch industry has a share of 12% in total GDP, which is lower than the EU average. The most gas intensive sectors are the chemicals industry (25% of total gas consumption and 2% value added) While the food industry takes a 7% share of total gas consumption and has a value added of 2%, we deem it unlikely that this industry would be asked to shut down by the government.

The biggest economic impact on the Dutch economy could come from industry stoppages in other Eurozone countries (primarily Germany) which indirectly affects Dutch firms and demand for Dutch exports via supply chains. Emergency gas plans signal that larger industrial companies are expected to face energy rationing before SMEs, and as large companies are more integrated in global value chains, this may have a disproportionately bigger effect on Dutch trade as well. Interestingly, the sectors affected by this indirect effect are different than those hit by the direct effect. Trouble in supply chains will primarily affect the manufacturing of clothing (0.15% of Value Added) and mining (1.03% of VA) sectors and to a lesser extent Agri (1.8% of VA) and metals (1.4% of VA). Whilst the impact in terms of lower growth and higher inflation will already become visible towards the end of 2022, we judge that the main impact will come in 2023. Growth is expected to be severely reduced – likely in a recession – and inflation will stay elevated more in 2023.

Policy implications for the ECB and Fed

A gas stoppage would exacerbate inflation over the next year but also likely causes a deep recession. This creates even more uncertainty over the policy direction of the ECB. In terms of the path for interest rates, a crucial factor will be when exactly the new scenario becomes clear and also the degree of fiscal support to households and firms. On balance, we think that the new scenario will likely lead to a lower path for interest rates than in our baseline. Although ECB policy rate rises to get policy closer to normal (and at least into modest positive territory) still look likely, the terminal rate will likely be lower than in the current base. A recession and rising unemployment will likely lead to a lower outlook for inflation in the medium term compared to the ECB’s current projections. As such, once the ECB factors this outlook into its projections, interest rate hikes are likely to be put on ice. The new scenario will also likely trigger more turmoil in markets, possibly with disorderly moves, leading to a sharp tightening financial conditions as well as more severe fragmentation in terms of peripheral spreads. The ECB may therefore need to move to non-sterilised net purchases of peripheral bonds and eventually a broader QE programme with the aim of stabilising markets as well as spreads. The profile for bond yields will be lower than in the base case and could fall quite significantly in 2023. For the Fed, we do not expect much impact from a Russian gas cut-off. The US is largely energy independent, and if anything a gas cut-off only puts more upward pressure on US inflation as it would raise demand even further for US LNG exports. While the US economy might be hurt from a demand angle given the recession we would expect in Europe, this would be less of a concern than in normal times given that there is still significant excess demand in the US economy. With Fed Chair Powell making clear in recent remarks that achieving price stability is ‘unconditional’, we think only a truly disastrous scenario for Europe involving a sustained disorderly tightening of financial conditions might derail Fed rate hikes.

China, a counterbalance for growth…

From a global growth perspective, China could function as a counterweight to the expected slowdown in the key developed economies in the coming quarters (even though we will cut our annual growth forecasts as we will explain in the regional part). That said, China’s rebound from lockdowns in March/April will be unbalanced, bumpy and less spectacular than the recovery seen after the initial covid-19 shock in 2020. The recovery in industrial output and the fading of bottlenecks in production and transport is also beneficial for global supply chains.

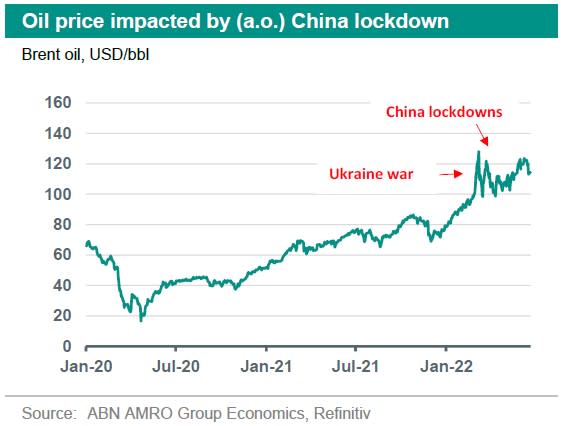

…and an additional upward pressure on energy prices

While the rebound in China may form a counterweight in global growth terms in the coming quarters, a pick-up in China’s demand and supply will add to the price pressures in global markets for energy, other commodities and industrial goods. Our base case of a gradual reopening in China is supposed to have an upward effect on energy prices while on the other hand it should help to reduce delivery times in global supply chains, and as such have a (ceteris paribus) downward effect on industrial goods prices. Depending on the severity of industry stoppages, global supply chains will again be disrupted and partly reallocated due to energy rationing in Europe, price increases and lower trade volumes. This would add to the structural realignment in global trade flows, as we already incorporated in our baseline scenario since the war in the Ukraine.