UK Election - A shift to the left, but brace for a right-wing re-alignment

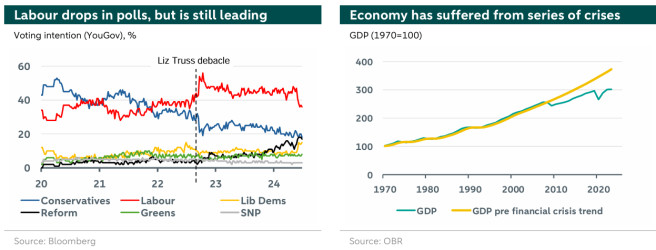

After 14 years of Tory rule, the British are ready for change this Thursday. The Liz Truss debacle, healthcare waiting lists, teacher shortages, and scarce housing drive voters to Labour. Tories may even end third, after Reform UK. An alignment of the two parties after the elections is conceivable. The next Labour government lacks fiscal space for fundamental policy changes, nor will it reconsider Brexit. The change in government will therefore not affect growth and inflation prospects, indeed, stubborn inflation will limit the Bank of England’s plan to lower interest rates.

Snap UK elections on 4 July

Britons are going to the ballot box this Thursday. The vote is somewhat earlier than expected, with Prime Minister Rishi Sunak calling parliamentary elections at an unfavourable time for his party. After 14 years of Tory rule, the British are ready for change. Britons have not forgotten the scandals during the pandemic under Boris Johnson, nor the financial calamity that struck the United Kingdom when Liz Truss briefly took over. Financial market investors punished her proposals for drastic tax cuts with a fall in the pound and higher interest risk premiums on government bonds. This ultimately led to the downfall of her government, but the severe damage to the Conservatives’ credibility on fiscal and economic policy has been lasting.

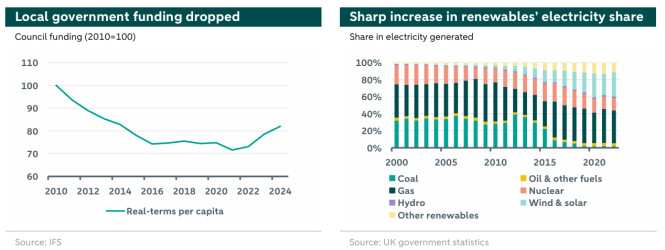

Economically, the Conservatives did not meet up to voters’ expectations. While unemployment is low, real wages have barely risen in recent years, causing Britons' disposable income to fall back relative to other countries. Moreover, healthcare waiting lists continue to grow, teacher shortages are increasing and housing is scarce and expensive. On top of this, the quality of local services has deteriorated because of the cuts in council grants. Finally, the Brexit issue: migration. The Tories have not succeeded in curbing immigration. On the contrary, the number of immigrants has increased, driven by those coming from outside the EU.

It is therefore not surprising that The Conservatives are doing badly in the polls. What also does not help is that their already unpopular leader Rishi Sunak is committing one blunder after another during his campaign. Another factor is that Nigel Farage, the chief cheerleader of Brexit, has recently become Reform UK's list leader, attracting disappointed Tory voters. There is even a chance that – in terms of vote share – the radical right Reform UK pass the Conservatives.

Given the ‘first past the post’ electoral system, in which the candidate with the most votes in a given regional constituency wins one of the 650 seats in parliament, the fragmentation on the right of the political spectrum weakens the position of right-wing parties. As such, while Reform may get 15-20% of the popular vote, it will probably only win a handful of seats in parliament. The bias in the electoral system, which favours large parties over smaller parties, could lead up to an alignment of the Conservatives and Reform UK after the elections. Effectively that would imply a rightward shift of the former Conservative party.

Labour still clearly leading the polls, despite the recent dip in support

Notwithstanding the recent drop Labour is heading for a strong score, according to the polls. In addition to voters being fed up with Tories and the fragmentation on the right, Labour is also helped by the Scottish National Party. The SNP is less popular because of its internal problems and because, for now, there is no prospect of Scottish independence, a key theme of the party. Scottish voters are expected to switch to Labour.

Although Labour campaigns with the slogan "change," we do not think government policy will change after the election. Since taking over the leadership of the Labour party from the far-left Jeremy Corbyn, Keir Starmer has steered the party to a more centrist policy agenda. Starmer is more in tune with former Labour Prime Minister Tony Blair and his finance minister Gordon Brown, who embraced market thinking with New Labour in the late 1990s. However, Starmer is more critical of globalization than Blair and Brown, and more concerned with globalization’s adverse effects on the distribution of income and wealth.

Starmer has moved to the right in terms of his views over the years, in part to attract centrist voters. He assumes that voters on the left have few alternatives and will vote Labour anyway. Starmer has since backtracked on promises he made in the battle for party leadership, such as the plan to abolish tuition fees for British students, or his intention to roll back privatizations of postal, energy and water companies. Another example is Brexit. In the past, Starmer wanted to hold a referendum on rolling back Brexit. Now he is keeping a low profile on this still thorny issue for the British.

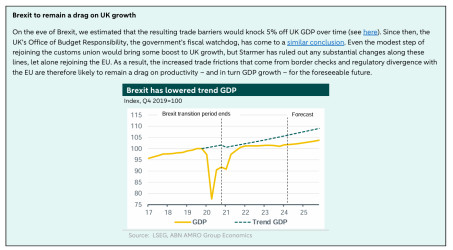

No reversal of Brexit any time soon

A low profile on Brexit is not to say that British policy toward Europe will remain entirely the same with Starmer at the helm. The Conservatives have been betting on trade deals outside of Europe in recent years. Apart from deals with far-flung, smaller economies, they came home cold, with limited interest from larger trade partners such as the US and China. Starmer is expected to push for regulation that is not too out of step with that of the EU, to keep trade frictions with the UK’s biggest trade partner to a minimum. But not much more than that.

Financially, Starmer has little room for radical adjustments. Public finances have weakened after a period of weak GDP growth and high government spending related to Covid and the energy crisis. Thus, there is not much money for stimulus measures. Rather, tax increases are on the agenda. In its manifesto, Labour announced GBP8bn in proposed tax increases. These include taxes for wealthy so-called ‘non-doms’ (an archaic tax status given to residents with overseas ancestry), measures to combat tax avoidance, higher VAT on private schooling, extra taxes for large energy companies that profit excessively from energy price increases, and a reversal of inheritance tax cuts made by former chancellor George Osborne. Labour wants to use a total of GBP5bn of this amount to improve the quality of public services and to put them on a more sustainable footing.

Much of Labour's attention will be on the housing market in the coming years. The number of new homes built has long failed to keep up with demand. Labour promises to add 1.5 million homes over the next five years. To achieve this, the number of annual homes constructed needs to be doubled. A key tool for this is more flexible zoning regulation. In addition, Labour is studying tax measures that encourage councils to allocate land for housing. Proceeds from such a tax incentive could also help to reduce council taxes, which are regressive in nature and hinder a more equal distribution of income.

NHS and education need reform

Other prominent issues are the NHS and education reform. In recent years, more money was allocated to health care. But health care costs rose even faster because of the complex care demands of an ageing population that deals with more frequent obesity and mental issues. The NHS’s problems cannot necessarily be solved by just spending more money. The organization of the healthcare system also needs attention. The same applies to education. Teachers quit because the workload is too high and jobs in other sectors give them more latitude.

Then there is the need for greening the economy. Labour proposes to allocate an extra GBP24bn over the next few years. The UK has already made progress in generating renewable energy. Now the problem is that electricity grid has too little capacity and investment is needed. Investments are also needed to reduce household energy consumption by making homes more sustainable. Compared to other countries, the housing stock is old and poorly insulated. Labour spends GBP1.1bn annually to improve homes with unfavourable energy labels. Lastly, Labour plans to set up a state-owned green energy utility company.

Housing, health, education, and sustainability targets will be difficult for Labour to meet without a growing economy. Currently, economic growth is based primarily on increases in the number of hours worked. But there is an upper limit to this. It is therefore necessary to improve productivity. Productivity growth declined steadily during the financial, covid and energy crises, while Brexit strained potential growth. If the economy had maintained the same growth rate after 2008 as before the financial crisis, the economy would be a quarter larger today.

Productivity boost required

Declines in productivity growth are not unique to the UK. Still, there are factors specific to the UK. First, the economy relies heavily on the services sector and the productivity of its most productive component – the financial sector – is under pressure. Second, all sectors perform worse than comparable sectors abroad in terms of productivity growth. Third, there are major differences in productivity across regions. Overall, London stands far above the other larger cities. In other countries, regional differences are much smaller.

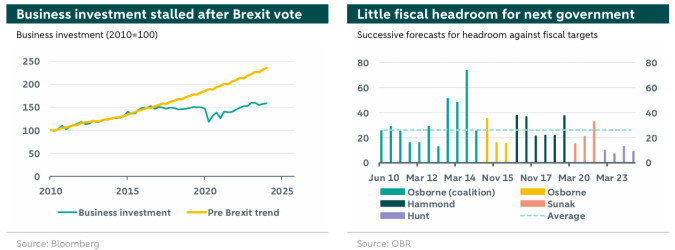

There are explanations for the stagnation of productivity growth. A fundamental problem is the poor condition of transport infrastructure. In addition, only a small share of GDP goes to training. The level of education falls short, and a large share of the workforce is underqualified. Finally, business investment is at a low level, despite businesses being in healthy financial shape. This is due not only to the service-oriented nature of the economy, but also to non-tariff and regulatory trade barriers that entrepreneurs face because of Brexit (see Box on page 3), and their limited access to venture capital.

Macro Outlook: Minimal impact from election; sticky wages to keep rate cuts gradual

As we approach the general election, the UK economy has finally shown signs of life, with growth rebounding 0.7% q/q in Q1 this year. This followed almost two years of stagnation, and even a short technical recession in the second half of 2023. The UK – alongside other European economies – was hard hit by the energy crisis and in particular the shock to real incomes. With high nominal wage growth having now largely made up for the price shock, and inflation much lower, real wages are finally making some positive headway. This is giving a lift to private consumption. A further support is coming from lower interest rates. While the Bank of England is yet to start cutting rates, lower government bond yields in anticipation of rate cuts are already providing some relief in financing costs for both businesses and households. This is particularly so due to the much higher share of short-term fixed rate mortgages in the UK compared to other countries (with 2- and 5-year fixed rates the most commonplace). This means that interest rate changes impact the economy with a shorter lag than elsewhere.

Looking ahead, we expect the economy to continue recovering this year, but to grow at a below trend rate (see table at the end of this publication). As described above, the lack of fiscal space for the incoming government leaves little room for bold tax and spend changes, and the changes that Labour has proposed are likely to have a limited (close to negligible) growth impact. The one non-fiscal policy lever that could make a difference – Brexit – remains a taboo subject. As such, while the election will herald a significant political shift, its economic impact is likely to be close to negligible.

UK’s stubborn inflation problem will keep rate cuts gradual

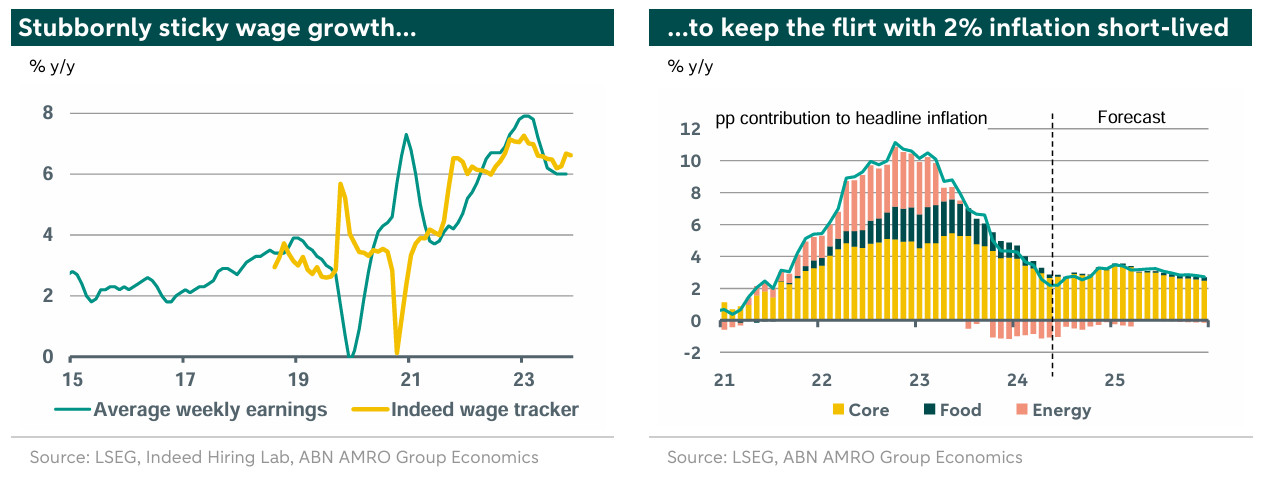

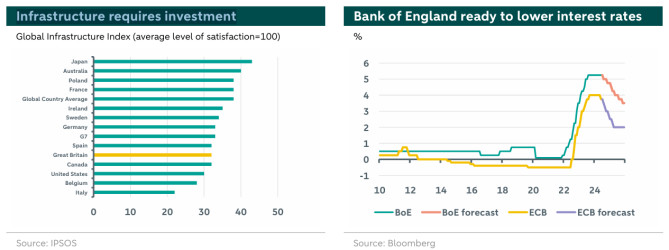

This leaves monetary policy as the main potential source of stimulus, but here too, there are limits on the pace at which the Bank of England can lower rates. This is because wage growth, at over 6%, remains far above levels consistent with inflation staying at 2% over time. Inflation is a deeper-rooted problem in the UK that predates the pandemic and the energy crisis. In contrast to the US and the eurozone, the UK never faced the ‘problem’ of too-low inflation in the post-2008 financial crisis period, but rather faced a smaller albeit idiosyncratic inflation shock from the collapse in sterling following the 2016 Brexit referendum. This meant the starting point for inflation expectations in the UK was significantly higher pre-pandemic than in the US and the eurozone.

As a result, although wage growth has peaked and is expected to slowly fall back to more normal levels, in the mean time it is likely to drive a renewed firming in inflation. Headline CPI inflation only just returned to the BoE’s 2% target in May, helped by the lagged pass-through of lower energy prices. However, we expect this flirt with the BoE’s target to be short-lived. As the energy drag fades, we think core inflation will stay stubbornly high, driving a rebound in headline inflation. Due to the dovish tilt of the MPC, we still expect the BoE start a rate cut cycle this coming August. However, we think sticky inflation will temper the pace of these rate cuts, and as such we expect just two 25bp cuts this year, and four 25bp cuts next year. This would still leave Bank Rate in restrictive territory by the end of next year, at 3.5%. Some support, but no panacea.