SustainaWeekly - The impact of climate change on the neutral rate of interest

In this edition of the SustainaWeekly, we start with the impact of climate change on the neutral rate of interest. We go on with the second of a set of three notes on the electricity sector, where we discuss how different scenarios look at electricity demand growth for the upcoming years. We then discuss how a possible framework for the ECB to decarbonise it covered bond holdings could potentially look like. Finally, we show that the carbon-free transition in key sectors of the Dutch economy still faces enough obstacles.

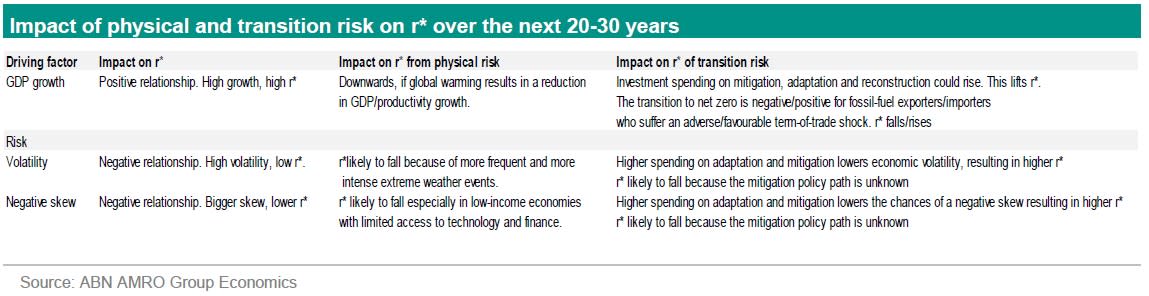

Strategist: Climate change and the response to it will generate multiple countervailing influences on r*, which is the neutral or equilibrium rate of interest. Theory shows that r* is determined by three factors - GDP/productivity growth, demographics and the preference for safe assets. Rising temperatures will result in more frequent and intense extreme weather events that will raise the demand for safe assets and a consequence of that is lower r*. The outlook for r* depends on the size of the transition and physical shocks.

Economist: This is the second of a set of three notes on the electricity sector. In the first note, we highlighted the divergence in electricity demand in OECD and emerging market economies. Going forward, under different scenarios, the demand for electricity is expected to rise in both OECD and emerging economies because of decarbonisation and energy security.This marks a shift from the past 10 years in the OECD where electricity demand was flat.

ESG Bonds: Ms. Isabel Schnabel indicated that the ECB is looking into potentially decarbonising (or greening) its covered bond portfolio. It seems therefore likely that the ECB is now working on a framework that it can use for that purpose. In this piece, we discuss how such a framework could look like.

Sector: Within many of the economic sectors of the Dutch economy, the transition to low or zero carbon is well underway. But some sectors still face a heavy emission reduction path, while for a small number of others, the emission reduction pathway toward 2030 is a viable option. The sectors responsible for most greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions face a major challenge to decarbonise their processes and products. The transition is often complex and also faces many obstacles.

ESG in figures: In a regular section of our weekly, we present a chart book on some of the key indicators for ESG financing and the energy transition.

The impact of climate change on r*

This note discusses the impact of climate change on the neutral or equilibrium rate of interest (r*). r* is of profound importance for monetary policy, asset prices and fiscal policy

r* is a theoretical concept and the measure evolves over time. Theory shows that r* is determined by three factors - GDP/productivity growth, demographics and the preference for safe assets. r* also helps balance savings with investment

The outlook for r* depends on the size of the transition and physical shocks. There is a trade-off between physical and transition shocks; the physical shocks will be smaller (bigger) if governments make a meaningful (poor) effort to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The uncertainty around policy could exert downward pressure on r*

Rising temperatures will result in more frequent and intense extreme weather events that will raise the demand for safe assets and a consequence of that is lower r*. The prospect of more frequent and intense weather events could also deter investment spending altogether, again lowering r* and further amplifying the search for safe assets

A carbon tax will lower the demand for and the price of fossil fuels. This adjustment will be particularly painful for fossil fuel exporters who will face an adverse terms-of-trade shock during the transition. The shock will be favourable for importing countries. Global r* will represent a balance of these two effects

r* balances desired investment with desired savings. Investment on mitigation and adaptation is forecast to rise by around 1-2% of GDP annually for the next 20-30 years under a net zero scenario. This will raise the demand for savings with upside pressure on r*

“The humans of the future will surely understand, knowing what they presumably will know about the history of their forebears on earth, that only in one, very brief era, lasting less than three centuries, did a significant number of their kins believe that planets and asteroids are inert. My ancestors were ecological refugees long before the term was invented. By Amitav Ghosh in The Great Derangement. Climate Change and the Unthinkable”

In this note we discuss the impact of climate change on the neutral or equilibrium interest rate. The equilibrium rate is the level of the real short interest rate when the economy is in equilibrium i.e. when the economic activity is at potential and inflation is on target. It is also the level at which savings are equal to investment. Economists refer to equilibrium rate as r*.

The equilibrium rate is of profound importance to central banks, governments and investors. Monetary policy makers at central banks continuously calibrate monetary policy to r*. The policy stance is said to be expansionary when the official policy rate is below the equilibrium rate and restrictive when the policy rate is above the equilibrium rate. r* is important for government policy, especially when the central bank interest rate is at the lower bound and the government needs to step in with structural reform to raise potential economic growth or with a fiscal stimulus, as has been the case recently. And finally, r* is fundamentally important for asset returns because, ultimately, all asset prices are benchmarked against the risk-free interest rate.

What drives r*?

r* is a theoretical concept and the precise level is unknown. In fact, not only is the precise level of r* unknown, it also thought to vary over time. For example, the equilibrium rate has been on secular downtrend in advanced economies since the 1980s.

There are many explanations for this downtrend and in line with economic theory, they can be grouped into three buckets – economic growth, demographics and the rising preference for safe assets. These drivers are structural in that they evolve gradually over time. For example, one important reason for the decline in advanced economy real interest rates since the 1980s is slower economic growth caused by lower productivity growth over this period. Low economic growth requires less investment and that in turn requires less savings, resulting in a reduction in r* because the equilibrium rate helps balance savings and investment.

r* is not only influenced by the average rate of economic growth, it is also impacted by the volatility of that growth and the skewness around that growth. To be clear, it is the growth in productivity/GDP rather than the level of productivity/GDP that matters for r*. By way of intuition, economic agents prefer safety and agents are prepared to pay a premium for assets that offer the same safe payoff in all outcomes and especially in periods when the economic outlook is volatile.

For that same reason, agents are prepared to pay a premium when the skew in the distribution of outcomes is negative i.e. the chances of a bad outcome exceeds the likelihood of a good outcome.

Climate change and r*

Climate change and climate change policy are important for productivity growth and investment spending. High investment spending will boost GDP in the short run and support the long run productive capacity of the economy. GDP will also be less volatile. Higher GDP growth and lower GDP volatility will result in higher r*.

Physical shocks

One way to frame the discussion is through the prism of physical and transition shocks. Physical shocks relate to direct and indirect risks to the economy that are caused by global warming. These risks can be chronic or acute. The chronic impact stems from the effect that rising temperatures have on labour productivity, labour supply, total factor productivity and capital accumulation. The majority of recent climate literature appears to suggest that global warming will lower the level of productivity and GDP rather than the growth in productivity and GDP. The impact of chronic physical shocks on r* will be relatively small if, as studies suggest, the effect on the growth rate of GDP is marginal.

Acute physical risk is also closely associated with temperature. GDP is expected to be more volatile, especially in small, low income economies that are densely populated and prone to extreme weather events. Low-income economies are also more vulnerable because they are less able to access the technology and finance that will be necessary to build resistance and to rebuild the economy after an extreme weather event. The quote from Amitav Ghosh above highlights the fragility of the economy in one such country, Bangladesh. In fact, studies show that global warming of 1.1 degrees has already doubled the global land area and population that is exposed to extreme weather events such as flood, crop failure, heatwaves and droughts. These events will only multiply and potentially bring with them increased migration and conflict, resulting in more volatile GDP. The preference for safe assets will rise, exerting downward pressure on r*.

Extreme weather events could also raise the demand for investment which will support r*, but equally, a scenario can be painted where the increased frequency of extreme weather events deters investment spending and in that case, r* could fall. Low-income countries with limited access to finance and technology are most vulnerable. The corollary of low mitigation and adaption investment spending could be an increase in demand for risk free assets.

Transition shocks

Transition shock is the impact on the economy of changes in climate policy and technology. The literature on transition shocks is centered around price-based policies such as carbon taxes and non-price based policies such as regulation, public investment and incentives for green investments. Carbon tax will raise the effective price of carbon-intensive fuels such as coal, oil and gas relative to nuclear and renewables. As a result, demand will shift away from fuels, especially high-carbon fuels, and towards low carbon fuels. The production process will also switch towards capital and labour and away from energy. The underlying price of fossil fuels will fall because of lower demand. Lower fossil fuel prices and demand will act as an adverse terms-of-trade shock for fuel exporters such as countries in the Middle East, Canada, Norway, and Russia. On the flip side, fossil fuel importers such as the EU, Japan, China and India will benefit from the lower price.

As discussed previously, the equilibrium rate of interest also serves to balance savings with investment. The power sector sits at the centre of this transition and investment will have to rise substantially over the next 15 years in this sector to achieve net zero. The Energy Transition Commission believes that a complete transformation of the energy system is required to achieve net zero by 2050 and that will cost 1-2% of GDP per annum. This is the total estimate of investment to replace/retrofit the existing fossil fuel-based infrastructure with clean energy, but what matters for this analysis is the incremental investment that needs to occur over and above regular fossil fuel investment that would have been undertaken under a no climate change scenario. McKinsey, the management consultant, estimates that the net investment required is in the region of 1% of GDP. This amount of investment is unaffordable for most governments and as a result, the private sector will have to play an important role in funding and building the required infrastructure.

To this we need to add the cost of adaptation projects to guard against the physical effects of climate change. This includes upgrading public infrastructure such as irrigation systems, roads, bridges, buildings and developing early warning systems. Spending on transition and adaptation must be matched by additional savings and r* will need to rise to encourage the private and public sector to channel savings into these investment projects.

Conclusion

Climate change and the response to it will generate multiple countervailing influences on r*. Theory states that r* will be influenced by economic growth and the uncertainty around that growth r* also acts to balance savings with investment. The overall impact will depend on the balance of these forces. Higher mitigation and adaptation investment spending will raise r* and in these circumstances we expect the demand for safe assets to ease which, in turn, will also support r*. The converse is also possible – investment spending could be low and the risk to the economy will rise. Both forces will act to dampen r*. Fossil fuel exporting countries will suffer a loss in income because of adverse terms-of-trade shocks, meanwhile the purchasing power of fossil fuel importers will improve because of the favourable terms-of-trade shock. Global r* will reflect a balance of these two factors.