SustainaWeekly - The Green Bubble and other scenarios

The Network for Greening the Financial Sector (NGFS, a group of central banks and supervisors sharing best practices in environmental and climate risk management in the financial sector) recently published a concept note on short-term climate scenarios, including additional colour on financial and short-term effects. In this week’s SustainaWeekly we first explore the scenarios and key innovations presented compared to what has been done previously. In a separate note, we provide a brief description of what biodiversity is, what are biodiversity-related risks, how these risks are measured, and what regulations/policies are currently in place. A longer thematic on this topic will be published soon. In our final note, we analyse to what extent synthetic fuels can replace fossil fuels, taking in some of current challenges.

Economist: The NGFS recently published a concept note on short-term climate scenarios, including additional colour on financial and short-term effects. In comparison with earlier scenarios, they are more suited for macroeconomic forecasting on the one hand, and stress testing on the other. As well as scenarios that have similar elements to the past, such as Sudden wake-up Call and Highway to Paris, the Green Bubble is a relatively new one.

Strategist: There are two types of risks associated with biodiversity. Physical risks stem from the loss of biodiversity and transition risks stem from regulations/policies introduced by regulators to mitigate biodiversity loss risks. Several central banks have calculated their national financial institutions exposure to biodiversity risks. Results are discouraging, but regulators have already a few regulations in place to try to mitigate the loss.

Sectors: Fossil fuels could be replaced by less polluting synthetic fuel alternatives. Renewable diesel and bio-diesel can replace petroleum diesel. E-methanol, bio-methanol or solar methanol can replace methanol and green hydrogen can replace blue and grey hydrogen. However, these more sustainable fuels are expensive, most have limited availability and have numerous other challenges.

ESG in figures: In a regular section of our weekly, we present a chart book on some of the key indicators for ESG financing and the energy transition.

NGFS scenarios enriched with short-term and financial narrative

The NGFS recently published a concept note on short-term climate scenarios, including additional colour on financial and short-term effects

In comparison with earlier scenarios, they are more suited for the main purposes of macroeconomic forecasting on the one hand, and stress testing on the other

The shorter time horizon and inclusion of financial shocks could help to construct plausible scenarios, combining elements of a number of those scenarios, for instance for the purposes of stress testing

New NGFS scenarios approach has been published

The Network for Greening the Financial Sector (NGFS, a group of central banks and supervisors sharing best practices in environmental and climate risk management in the financial sector) recently published a concept on short-term climate scenarios, including additional colour on financial and short-term effects. These scenarios have not yet been quantified: the approach and scenarios have been published in a concept note. Still, the note is very interesting as it takes steps towards making climate scenarios specifically suitable for the main purposes: macroeconomic forecasting on the one hand, and stress testing on the other. Due to the short term nature of the scenarios, they can account for shocks that have a short-term impact and subside in the medium term (such as shorter-lived confidence/financial market effects). Including these types of shocks is a step towards more realistic scenarios, and a shift away from stylised examples.

Setup of the scenarios and salient points

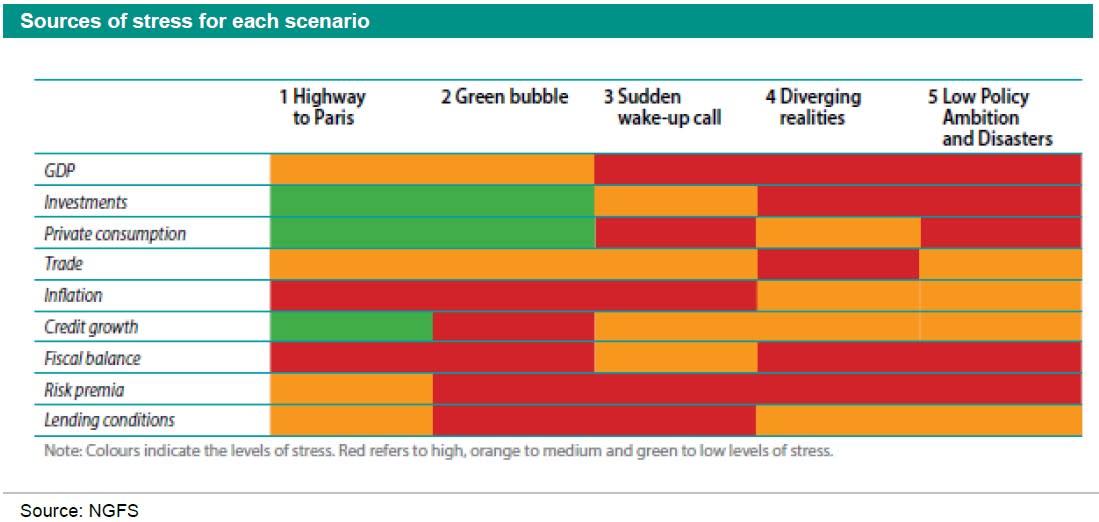

In the new setup, each scenario has climate shocks (policy or physical) and macro financial shocks. There is an emphasis on adverse scenarios given their use to test the resilience of economic and financial systems.

There are 3 example pathways in which net zero is reached. Firstly, the “Highway to Paris” scenario, which is closest to the “orderly net zero” in which the carbon tax increase is expected and a boom in green investment is financed by carbon taxation. The negative shock from the carbon tax and the positive shock from the investment boom lead to an on balance favourable economic outcome. The “Green Bubble” disorderly scenario is one where net zero is reached, but with subsidies rather than taxes incentivising the green shift (comparable to the US Inflation Reduction Act, all carrots, no sticks). This leads to a glut of private investment and an increase in debt. In this example pathway, the green investment bubble bursts at some point, leading to a confidence crisis and increased risk premia. The “Sudden wake-up call” disorderly scenario reflects a world of widespread climate ignorance, which is challenged by a sudden change in policy preferences, triggered by for instance a surprise election result favouring green parties or a natural disaster. This leads governments to hastily implement a stringent mitigation pathway, leading to a speedy re-allocation of capital from polluting to green sectors. The sudden and unanticipated nature of climate policies leads to financial turmoil and a crisis of confidence.

There are two example pathways in which Net Zero is not reached. In the “Diverging Realities” disorderly scenario some countries do transition quickly but others do not, so that the global context is one of an ineffective transition in which net zero is not reached. As a result, the countries that do transition are presented with strong transition, as well as physical risks. Such a scenario would be the result of for instance lack of finance in emerging markets and developing economies. As disaster-prone areas suffer from the fallout, supply chains are disrupted and economic activity stalls. Migration flows to less affected areas. Risk premia rise as the most plausible scenario shifts. The hot house world scenario “Low policy ambition and disasters” is about physical risk manifesting in the short term. This is not so much related to the emissions pathway in the scenario, as physical risk is dependent on emissions of previous years (lagged response). The focus in this scenario is on: “How to model/transmit physical risk shocks into the economy?”. In this scenario, natural disasters lead to a spike in risk premia while supply chains are disrupted, real estate prices drop in affected areas and households consume less and save more. An important point in scenarios with high physical risk is the response of (re) insurance sectors, as increased insurance premiums can lead to chilling effects on economic activity and delayed or abandoned investment due to higher costs, or even unavailability of, insurance (see for instance our note here on this topic).

Incorporating acute physical shocks

To incorporate the impact of (acute) physical shocks on the economy in a short-term climate scenario, there are a few options. The first option is that of implementing a specific physical shock. Depending on the nature and location of this shock this could be for example via sectoral added value, supply of production factors, production or services disruption. The risk and severity of a shock can be assessed with Natural Catastrophe models, that take into account the latest science on the characteristics of extreme weather events and the impact of climate change more broadly. As most severe natural disasters are expected to occur beyond the short-term time horizon, it may be useful to incorporate future shocks (that are due to current lack of abatement) forward in time.

Secondly, acute physical shocks can be incorporated via the effects of an increased risk of natural disasters. For instance, the sudden reassessment of the likelihood of acute physical risk in the future can manifest itself as a shock to expectations on any of the above-mentioned variables and reduced investment spending and increased uncertainty. Such a confidence shock could be captured via a shock to expectations. An uncertainty shock could be captured via an increase in the equity and/or sovereign risk premium.

Energy and critical materials prices

Other relevant shocks for the transmission into the macrofinancial environment are shocks to energy and critical materials prices. With regards to energy prices, the NGFS notes that it is useful to take into account the feedback loop between carbon and energy prices. First, carbon prices are likely to trigger an energy price shock due to the direct impact of carbon prices on the price of fossil fuels, which are still an important source of energy. These higher prices then incentivise the switch to clean energy. However, if fossil fuel prices are already high for a non-carbon price related reason, carbon prices need not be as high to incentivise a GHG reduction. Still, in this case the increased fossil fuel revenues flow to fossil fuel producers, while, on the other hand, carbon revenues flow to the public sector which may then chose to recycle them back into the economy, turn them into incentives for greening. Thus, the GHG reduction would not be as permanent as one that is caused by emission-reducing innovation and the economic impact would be less favourable.

Given that the path to net zero is paved with wind turbines, solar panels, and batteries, scarcity of critical materials, such as lithium, cobalt and nickel needed for these goods, such as lithium, cobalt, and nickel, are a real risk (see a note on this). Scarcity of critical materials could be captured by a proxy variable such as the cost of capital for green technologies. Another option might be to take into account price spikes on final goods relying on these critical materials.

Other main determinants of economic impact

The impact of climate policy is determined by their stringency (obviously) but other important drivers are the elasticity of substitution between fossil fuels and other forms of energy (very different per sector); and what the authorities do with the carbon revenues (the “recycling option”). The more revenue is rebated to households, the less demand falls and therefore the more prices will rise in response to the negative supply shock stemming from climate policies. Usually, governments care more about perceptions of fairness and political acceptability of their policies than the inflationary impacts. It is this likely that a politically feasible climate policy would entail some form of revenue recycling to households.

These elements make it possible to construct more realistic scenarios

These NGFS scenario still represent stylised examples to some extent. Still, we think that plausible scenarios will combine elements of a number of those scenarios. When looking at this mix of elements, it is clear that the mix will be different per country. There are some clear frontrunners, such as for instance the EU, and clear laggards such as for instance Russia. This important point is taken into account explicitly in the “Diverging Realities” scenario, where countries in transition are faced with both transition and physical risk.